MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6162

Case Report Volume 10 Issue 3

1General Surgery Service, High Specialty Medical Unit 25, Mexico

2Service of Angiology and Vascular Surgery, Hospital General de Zona No. 67, Mexico

Correspondence: Karen Aguirre-Flores, General Surgery Service, High Specialty Medical Unit 25, Monterrey, NL, Mexico

Received: December 18, 2022 | Published: December 30, 2022

Citation: Aguirre-Flores K, Mazariegos-Gutiérrez UE, Audiffred-Guzmán RA. Giant arteriovenous fistula pseudoaneurysm resection: case report. MOJ Surg. 2022;10(3):67-69. DOI: 10.15406/mojs.2022.10.00207

Introduction: It has been estimated that pseudoaneurysms appear in 4% of patients with autologous arteriovenous fistulas, mainly in the venous segment of those accesses with more than five years of evolution caused by rupture of the vessel wall and the consequent extravasation of blood to adjacent tissues.

Objective: Describe a case with a resection giant arteriovenous fistula pseudoaneurysm and a review of literature.

Case report: A 51-year-old male patient with a history of chronic kidney disease receiving renal replacement therapy through autologous arteriovenous fistula in the left thoracic limb and later kidney transplant from a cadaveric donor. His condition began with occasional mild pain at the level of the arm and forearm of the left thoracic limb, which progressed in intensity, partially limiting mobility and adding edema from the antecubital fold yo the distal point. He reported two isolated episodes of hypothermia and paresthesias that resolved spontaneously. A venous Doppler ultrasound was performed, finding the path of the fistula arteriovenous vein causing dilatation of the basilic vein with a thrombus inside. It was decided to dismantle the arteriovenous fistula, finding a venous path of the basilic vein of approximately 8 cm in diameter with a thrombosed upper segment. At the 1-month follow-up, the wound was found to have healed well and the patient was reported to be asymptomatic.

Conclusion: In patients with large, complex pseudoaneurysms, or with failed endovascular interventions, surgical management is the best option.

Keywords: pseudoaneurysm, complications, vascular access, arteriovenous anastomosis

It has been estimated that pseudoaneurysms (PA) appear in 4% of patients with autologous arteriovenous fistulas, mainly in the venous segment of those accesses with more than five years of evolution.1

Pseudoaneurysms are pulsatile and expandable dilations caused by rupture of the vessel wall and the consequent extravasation of blood into adjacent tissues, frequently as a consequence of an inadequate hemodialysis technique. Intraluminal hyperpressure associated with a vein wall weakened by repeated punctures seems to be responsible for this anomaly.2

A 51-year-old male patient with a history of chronic kidney disease receiving renal replacement therapy for 2 years through an autologous arteriovenous fistula in the left thoracic limb and later renal transplantation from cadaveric donor without complications. His condition began with occasional mild pain at the level of the arm and forearm of the left thoracic limb, which progressed in intensity, partially limiting mobility and adding edema from the antecubital fold to the distal point. He reported two isolated episodes of hypothermia and paresthesias that resolved spontaneously (Figure 1).

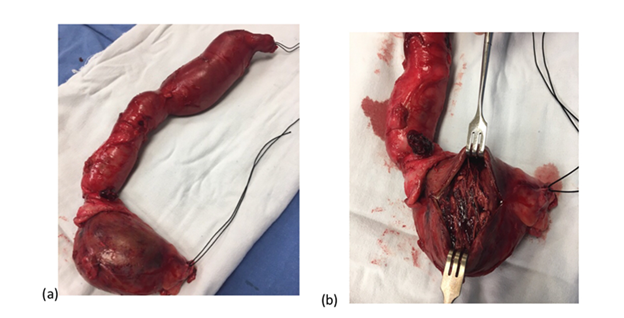

The patient had risk factors such as multiple trauma to the left arm and accesses with poor technique for puncture of the arteriovenous fistula when hemodialysis was performed. A venous Doppler ultrasound was performed, finding the path of the fistula arteriovenous vein causing dilatation of the basilic vein with a thrombus inside. It was decided to dismantle the fistula, previous surgical protocol, under general anesthesia, an incision was made in the internal face of the left arm, until vascular structures were identified, which were referred with silicone vascular loops, proximal and distal ligation of the venous segment was performed and its entire trajectory was dissected, finding a venous trajectory of basilic vein approximately 20 centimeters long by 8 centimeters in diameter thrombosed in its upper segment (Figures 2a & 2b). The tract was resected, hemostasis was verified, and closure was performed by planes until reaching the skin, ending the surgical procedure (Figure 3a).

Figure 2 Dismantled pseudoaneurysm associated with an arteriovenous fistula. Figure 2a Dismantled Pseudoaneurysm from the arteriovenous fistula in the patients left thoracic limb. Figure 2b Trajectory of the thrombosed basilic vein.

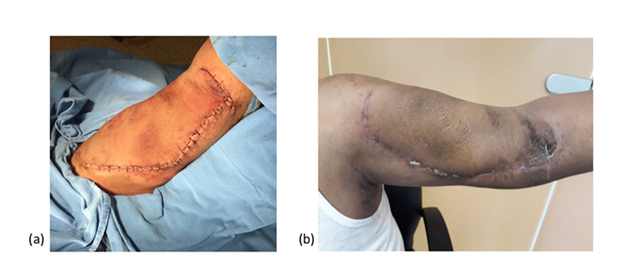

Figure 3 Successful vascular evolution in the immediate postoperative period. Figure 3a represents the left thoracic limb of the patient with a successful vascular evolution. Figure 3b represents the assessment of the patient 1 month after his surgery referring asymptomatic.

At the 1-month follow-up, the wound was found to have healed well and the patient he referred asymptomatic, denying hypothermia, paresthesias or pain (Figure 3b).

Complications of vascular access are responsible for 15% of hospital admissions for hemodialysis patients, therefore a multidisciplinary approach is essential for early detection.3 Among the most frequent complications in patients who undergo autologous arteriovenous fistulas for hemodialysis are: surgical site infections, seromas, hematomas, pseudoaneurysms, venous hypertension, arterial steal syndrome, heart failure, and arteriovenous access thrombosis.4

Pseudoaneurysms are relatively infrequent complications, and their incidence is even lower in autologous fistulas than in those performed with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft. The development of pseudoaneurysms implies not only a reduction in the useful life of the fistula, but also an increased risk of graft thrombosis, infection, dificult access, or even rupture.5

Arteriovenous fistula (AVF) with pseudoaneurysm (PA) is more frequently associated, secondary to vascular catheterization, percutaneous biopsy, surgery, or trauma. The AVF-PA occurs mainly in large or medium venous territories.6,7 In recent decades, therapeutic methods have evolved from surgical repair to less invasive options such as ultrasound-guided compression therapy (UGCT) and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI).8,9 In those cases that reach a small size, endovascular treatment (coated stent or thrombin injection) may be sufficient in an attempt to prolong the life of the vascular access. On the contrary, in cases like the one described, open surgery is the only effective treatment to avoid events that require urgent action.10,11

The diagnosis is generally clinical, the presence of an expandable pulsatile mass of progressive growth in the path of the vascular access should make us suspect it, since it is present in 67-100% of cases. Sometimes, patients may report pain or local edema and a thrill is usually palpable and a bruit is heard at the site of the mass if the pseudoaneurysm is patent. Although most times the clinical history and physical examination suggest the diagnosis, sometimes additional examinations are necessary to confirm its presence and establish the differential diagnosis with other tumors.1,2,12

Doppler ultrasound, as a non-invasive examination, provides sufficient information, since it has high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, being useful for confirming and determining the extension of the pseudoaneurysm, as well as visualizing the thrombotic material inside it, which are important data for when deciding whether or not surgical correction is necessary and the technique to be used, conventional or endovascular surgery.13

Despite the fact that fistulography has classically been considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of vascular access dysfunctions and anomalies, its high cost and the need to use contrast make it the second option in the diagnostic approach and it is only indicated when echo-Doppler does not provide sufficient information on the etiology and morphology of the lesion, prior to endovascular treatment or when distal limb perfusion is compromised. Magnetic resonance imaging is also used occasionally for the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysms.14 The treatment of aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms should be carried out as a priority due to the high risk of local and systemic complications that they entail.15

Regardless of the therapeutic option that is used, the indications of when the treatment should be carried out are agreed upon. According to the KDOQI (Kidney Diseases Outcomes Quality Initiative) clinical practice guideline for vascular access for hemodialysis from the National Kidney Foundation, when a pseudoaneurysm develops on a prosthetic AVF, it should be treated when:

There is no unanimity when it comes to establishing the treatment of choice in each case; some authors advocate traditional surgical treatment for dilatation repair while others advocate the endovascular option through stent implantation, embolization, or Doppler ultrasound-guided procedures using local compression or thrombin injection.16

The mainstay of treatment of pseudoaneurysms is surgical revision with resection or exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm and bypass of the affected segment.17 When the skin underlying the pseudoaneurysm shows signs of necrosis, it is necessary to cover the skin loss by skin plasty after repair of the leakage site. If the loss of substance is very important or there is superimposed infection, we are sometimes forced to ligate or exclude angioaccess.18, 19

In patients with a diagnosis of pseudoaneurysms related to large, complex arterial fistulas or with failure of endovascular interventions, surgical management is the best option.

None.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

©2022 Aguirre-Flores, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.