MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6162

Background: Laparoscopic Total Extraperitoneal Preperitoneal Hernioplasty (TEPP/TEP) is now a proven technique with reduced postoperative pain, rapid recovery, low failure rate, early return to activity/work and better patient satisfaction, but often criticized by rather higher rate of serious complications and recurrence.

Patients and Methods: A prospective doctoral research was designed in 2010, and TEPP hernioplasty was performed between 2011 and 2015 under institutional ethics’ approval and written informed consent through posterior rectus approach with 3-midline-port technique. Balloon dissector was used in first three patients.

Results: Sixty three adults were recruited. Three females excluded on inclusion criteria. Three males excluded on conversion. TEPP hernioplasty was successfully done in 60 adult male patients with 68 inguinal hernias (unilateral, 52; bilateral, 8). Mean endoscopic vision and ease of procedure were 8.20±1.33 (range 4.0-9.5) and 7.27±2.05 (range 4.0-9.5) respectively. Operation time were 113.4±34.8 (60-205) and 138± 40.2 (90-180) minutes for unilateral and bilateral hernia respectively. Minor complications included inferior epigastric vessel injury (1.5%), excessive CO2 retention (1.5%), surgical emphysema (16.2%), and peritoneal injury (28.3%), port-site infection (6.7%), Seroma (10.3%), temporary orchalgia (1.5%). Conversion rate was 4.8%, and average hospital stay was 3.3±1.7 (1-10) days. Follow up was 33.1±16.9 (5-61) months, which was extended for 43 months beyond the study period. Present study documented zero incidences for both major vascular/visceral complications and long-term recurrence.

Conclusions: Present study documented zero incidences for both major vascular/visceral complications and long-term recurrence. The philosophy of ‘Zero accident vision’ is attainable for TEPP hernioplasty with unhurried technique and dedicated motivation.

Keywords: laparoscopic hernioplasty, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal repair, TEPP, TEP, surgical outcome, clinical outcome, major complications, serious complications, recurrence, zero accident vision, zero vision philosophy, inguinal hernia, recurrent inguinal hernia, femoral hernia

TEPP/TEP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal hernioplasty; TAPP, transabdominal preperitoneal hernioplasty; Endovision, endoscopic vision; OT, operation time; EOP, ease of procedure; PI, peritoneal injury; PAC, pre-anaesthetic check-up; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Sciences; SD, Standard Deviation; EOP, ease of procedure; OPP, open preperitoneal; TAPP, trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal; PI, peritoneal injury; S-Emph, surgical emphysema; OPR, open preperitoneal repair; SOM, secondary outcome measure

Mesh repair of inguinal hernia has become a norm in our modern era with a recurrence rate of 1-5%.1 Laparoscopic Total Extraperitoneal Preperitoneal Hernioplasty (TEPP/TEP) proved an efficacious repair with reduced postoperative pain, rapid recovery, low failure rate, early return to activity/work and better patient satisfaction.2,3 However, despite the obvious advantages and better results, the initial enthusiasm and popularity suffered a significant setback because of the demanding nature of the procedure with a steep long learning curve, higher cost, and rather higher rate of serious complications and recurrence.1−6 Some recent reports revisited the procedure of the TEPP hernioplasty with zero rates of serious complications7−9 and recurrence, 9−12 a dream of every hernia surgeon. The author, a passionate operator and firm believer in zero vision for the serious complication and recurrence after herniorrhaphy/hernioplasty, achieved the target to a large extent during the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty as presented herein.

A prospective clinical research study was carried out in the Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College and Hospital, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India for award of PhD in Surgery. Laparoscopic total extraperitoneal preperitoneal (TEPP) repair was done adult patients for inguinal hernia under the ethical approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine (#770/FM/21.08.2013) and the written informed consent of the patients. The study was performed from April, 2010 to November, 2016. Recruitment criteria included

Inclusion criteria were: patient was included in the study if his/her age was 18 years or more, his/her physiological score was ASA Grade I & II (American Society of Anesthesiologists), his/her inguinal hernia has primary and uncomplicated, and his/her TEPP hernioplasty was completed successfully. Exclusion criteria were patient’s age less than 18 years, ASA Grade III-V, complicated inguinal hernia, recurrent inguinal hernia, femoral hernia, history of lower abdominal surgery, and patient’s reluctance for laparoscopic repair.

Patient’s weight was measured without footwear, and the Deurenberg’s formula was used to calculate his/her body mass index (BMI).13 Pre-anaesthetic check-up was regularly carried out in the PAC clinic of the outpatient department, and all patients were admitted one day prior to the operation as part of the general policy of our hospital. All TEPP hernioplasties were performed by a single experienced consultant surgeon (the author). In addition to the study of the posterior rectus sheath, arcuate line, transversalis fascia and preperitoneal fascia the details of which have been reported earlier by the author,14−30 the surgical outcome measures included endoscopic vision (measured on Visual Analogue Score of 1-10), ease of the procedure (measured on visual analogue score of 1-10), operating time (hours/minutes), conversion, peritoneal injury, and surgical emphysema; and the clinical outcome measures included post-operative seroma, post-operative infection, post-operative chronic groin pain, and recurrence of hernia.

Patients were planned for discharge from the hospital after 24-48 hours of surgery if there was no problem or excessive pain, with advice for removal of stitches on the 7thpost-operative day. As a protocol, all patients were followed up in the 1st and 4th week after operation, and thereafter, at 6 months and then yearly during the actual study period of 5 years. Moreover, the follow up was maintained diligently for a little more than 3 years beyond the study period. At times, mobile phone communication at the scheduled time was considered sufficient if patient had no discomfort/complaint and was permitted to make the visit at his own convenience.

Data were collected with instant documentation in a patient pro forma with video recording, and were analyzed through Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v. 21). Additional help was also taken for some simple statistical analysis from the On-line Calculators (www.graphad.com/quickcalcs/; www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/). All data were computed as Mean±SD (Standard Deviation) unless specified otherwise, and a p-value of <0.05 was taken as significant.

Standard 3-midline-port technique was utilized under the relaxant general anaesthesia with patient supine with 10⁰ head down, and the technique was consistently same as reported earlier by the author.14−28 Indigenous balloon made of a surgical glove fingerstall was used in only first three patients for the initial dissection in the supra- and retropubic regions, followed by instrument dissection under CO2 insufflation pressure of 12 mmHg. However, in the remaining patients of the study, the gentle to-and-fro movements of the tip of a 10-mm 0⁰ telescope through the first optical 11-mm port just below the umbilicus was utilized under CO2 insufflation for initial dissection under direct vision in the posterior rectus canal and the retropubic region, which was then followed by instrument dissection through the 5-mm ports-one in the suprapubic region and the second midway between the infraumbilical and the suprapubic ports (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Port Placement for Laparoscopic Total Extraperitoneal Preperitoneal (TEPP) Hernioplasty for Inguinal Hernia; F, foot end of patient; H, head end of patient; U, umbilicus; 1, infraumbilical site for camera port (11 mm); 2 & 3, sites for working ports (5 mm); 4, upper border of pubic symphysis; T, 11-mm metallic trocar with 10-mm 0⁰ telescope in-situ; Blue trocars, 5-mm plastic trocars) 17

The preperitoneal space was created underneath the transversalis fascia containing the deep inferior epigastric vessels by a combination of blunt and/or sharp dissection from the midline to the ASIS (anterior superior iliac spine). Parietalization of the cord structures was then carried out for at least 3 cm below the deep ring. A mesh of about 13-15cm (horizontal) x 12-13cm (vertical) in size was put in place. The mesh was often fixed with a single intracorporeal stitch at the pectineal ligament with 2-0 polypropylene suture to help in the spreading of the mesh and to prevent its future migration.

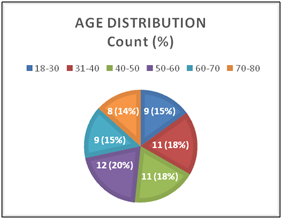

A total of 66 adult patients (Male, 63; Female, 3) with the uncomplicated primary inguinal hernia (Unilateral, 57; Bilateral, 9) were recruited for the study. The three female patients could not undergo TEPP hernioplasty due to one or more exclusion criteria and hence they were excluded from the study. Three male patients (One with left unilateral hernia, one with right unilateral hernia and one with bilateral hernia) were excluded due to early conversion to the laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal repair (n=1) and open preperitoneal repair (n=1), and open anterior mesh repair (n=1). Cause for the conversion included (1) peritoneal injury by the1st optical port just after its placement, (2) instrument injury to the deep inferior epigastric vessels by the roughened joint of the Maryland dissector just after placement of the middle working port, and (3) early haemodynamic instability secondary to excessive CO2 retention at the very outset. Therefore, the present study included only 60 patients who underwent 68 hernioplasties (Unilateral TEPP, 52 [Left, 35; Right, 17]; Bilateral TEPP, 8) for the data analysis. Patients were equally distributed across 3rd to 7th decade, (Figure 2) with a mean age of 50.08±17.15 years (Range 18-80 years), and mean body mass index (BMI) of 22.58±2.03 kg/m2 (range 19.5-31.2 Kg/m2). All patients studied were male, and 49 patients were in ASA grade I, while 11 patients were in ASA grade II. Fifty six patients had normal BMI of less than 25 kg/m2 (Mean BMI 22.17±1.27 kg/m2), and four patients had higher BMI of more than 25 kg/m2 (Mean BMI 28.35±2.02 kg/m2). Occupation of the patients varied from manual worker (n=24), retiree (n=9), office worker (n=8), student (n=7), field worker (n=6) and farmer (n=6). Fifty nine inguinal hernias were clinically indirect (Funicular 27; Complete 32) and nine inguinal hernias were direct (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Age Distribution (decade-wise) of the patients undergoing TEPP hernioplasty (N = 60).17

Figure 3 Distribution of clinical types of the inguinal hernias in patients undergoing TEPP hernioplasty (N=60).17

Primary outcome measures have been reported earlier by the author elsewhere.14-28 The surgical secondary outcome measures (endoscopic vision, ease of procedure, operation time, peritoneal injury, and surgical emphysema) and the clinical secondary outcome measures (postoperative seroma, infection, pain and recurrence) are described individually in the following paragraphs.

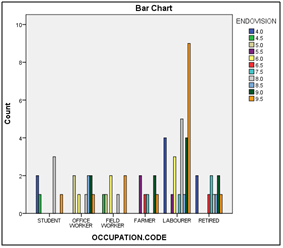

Endoscopic vision: Mean endoscopic vision (endovision) in terms of the visual analog score (1-10) was 8.20±1.33 (range 4.0-9.5). The endovision did not vary significantly with respect to the age, BMI and ASA grade of the patients Table 1. The endovision correlated significantly (p <0.05) with the nature of the patients’ work, but both the Likelihood Ratio and the Linear-by-Linear Association were not significant (Figure 4). The endovision also did not vary significantly with respect to the hernia types (unilateral vs. bilateral; direct vs. indirect) and hernia operation (Unilateral TEPP vs. bilateral TEPP; right TEPP vs. left TEPP; TEPP for Direct vs. TEPP for indirect hernia) Table 1. However, the simultaneous bilateral TEPP was associated with significantly lower endovision as compared to the unilateral TEPP (Table 1).

S. No. |

Variable |

Subgroups |

N |

Endovision Mean±S.D* |

CID ¶ |

**F / |

Sig. |

p-value |

Age |

18-40 |

20 |

7.25±2.14 |

-1.14 to |

0.261 |

0.771 |

>0.05 |

|

BMI |

Normal |

64 |

7.34±1.95 |

-3.622 |

-1.682 |

0.097 |

>0.05 |

|

Co- |

Absent |

56 |

7.56±1.95 |

-0.592 |

1.034 |

0.305 |

>0.05 |

|

Hernia Clinical |

Unilateral |

52 |

7.64±1.84 |

-0.41 |

1.427 |

0.159 |

>0.05 |

|

Hernia |

Unilateral |

52 |

7.64±1.80 |

-0.407 |

1.427 |

0.159 |

>0.05 |

|

Hernia |

Left |

25 |

7.44±2.11 |

-0.982 |

-0.004 |

0.997 |

>0.05 |

|

Hernia |

Indirect |

60 |

7.44±1.95 |

-1.462 |

0.006 |

0.995 |

>0.05 |

|

TEPP |

Unilateral |

58 |

7.78±1.80 |

0.605 |

2.723 |

0.008 |

<0.05 |

Table 1 Effect of demographic characteristics & anatomical variations on end vision during TEPP hernioplasty (N=68)

*SD, standard deviation; §VAS, visual analog score (1-10); ¶CID, 95% confidence interval of the difference; **F, ANOVA value; ***t, independent-sample t-test value; BMI, body mass index; TEPP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal hernioplasty; (Reproduced with permission from Ansari’s Thesis 17)

Figure 4 Correlation between Endoscopic Vision and Occupation (Pearson CHISQ CC: R = 68.363, df 50, Sig. 0.043, p <0.05; Likelihood Ratio: R=65.698, df 50, Sig. 0.067, p >0.05; Linear-by-Linear Association: R=1.006, df 1, Sig. 0.316, p >0.05). 17

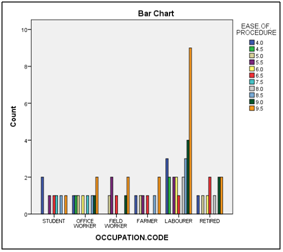

Ease of procedure: Mean EOP (ease of procedure) in terms of the visual analog score (1-10) was 7.27±2.05 (range 4.0-9.5). The EOP did not vary significantly with respect to the age, BMI and ASA grade of the patients Table 2. The EOP also did not correlate significantly with the nature of work (Figure 5). The EOP also did not vary significantly with respect to the hernia types (unilateral vs. bilateral; direct vs. indirect) and hernia operation (Unilateral TEPP vs. bilateral TEPP; right TEPP vs. left TEPP; TEPP for Direct vs. TEPP for Indirect hernia) Table 2. However, the simultaneous bilateral TEPP was associated with significantly lower EOP (p <0.05) as compared to the unilateral TEPP (Table 2).

S. |

Variable |

Subgroups |

N |

EOPɸ |

C.I.D¶ |

**F / ***t-value |

Sig. |

p-value |

|

1 |

Age |

18-40 |

20 |

7.28±2.09 |

-1.14 |

0.261 |

0.771 |

>0.05 |

| 2 |

BMI |

Normal |

64 |

7.17±2.07 |

-3.789 |

-1.630 |

0.108 |

>0.05 |

| 3 |

Co- |

Absent |

56 |

7.42±2.01 |

-0.461 |

1.287 |

0.203 |

>0.05 |

| 4 |

Hernia Clinical |

Unilateral |

52 |

7.50±1.95 |

-0.064 |

1.917 |

0.060 |

>0.05 |

| 5 |

Hernia |

Unilateral |

52 |

7.50±1.95 |

-0.064 |

1.917 |

0.060 |

>0.05 |

| 6 |

Hernia |

Left |

25 |

7.24±2.20 |

-1.089 |

-0.097 |

0.923 |

>0.05 |

| 7 |

Hernia |

Indirect |

60 |

7.28±2.03 |

-1.529 |

0.032 |

0.974 |

>0.05 |

| 8 |

TEPP |

Unilateral |

58 |

7.64±1.94 |

1.0793 |

3.227 |

0.002 |

<0.01 |

Table 2 Effect of Demographic Characteristics on Ease of Procedure (EOP) during TEPP Hernioplasty (N=68)

ɸEOP, ease of procedure; *SD, standard deviation; §VAS, visual analog score (1-10); ¶CID, 95% confidence interval of the difference; **F, ANOVA value; ***t, independent-sample t-test value; BMI, body mass index; TEPP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal hernioplasty; (Reproduced with permission from Ansari’s Thesis17)

Figure 5 Correlation between the Ease of Procedure (EOP) and the Patients’ Occupation: (Pearson CHISQ CC: R = 35.618, df 50, Sig. 0.938, p >0.05; Likelihood Ratio: R=43.779, df 50, Sig. 0.720, p >0.05; Linear-by-Linear Association: R=1.308, df 1; Sig. 0.253, p >0.05).17

Operation time: Mean operation time (OT) was 1.87±0.59 hours (range 0.75-3.25 hours). The operation time (OT) did not vary significantly with respect to the age, BMI and ASA grade of the patients Table 3. There was also no significant correlation between the OT and the nature of profession (Pearson Chi-Square, R = 79.366, df 70, Sig. 0.208, p >0.05) (Figure 6). The OT also did not vary significantly with respect to the clinical types of inguinal hernia (unilateral vs. bilateral; direct vs. indirect) and hernia operation (Unilateral vs. bilateral hernia; direct vs. indirect hernia). However, with respect to the operation category, there were significant differences between the unilateral TEPP vs. bilateral TEPP (p<0.001), right TEPP vs. left TEPP (p<0.05), unilateral TEPP vs. simultaneous bilateral TEPP (p<0.001) Table 3. In other words, the simultaneous bilateral TEPP was associated with significantly higher OT as compared to the unilateral TEPP (Table 3).

S. |

Variable |

Subgroups |

N |

OT§ |

C.I.D¶ |

**F / |

Sig. |

p-value |

1 |

Age |

18-40 |

20 |

1.99±0.55 |

-0.322 |

0.102 |

0.903 |

>.05 |

2 |

BMI |

Normal |

64 |

1.88±0.61 |

-0.352 |

0.846 |

0.401 |

>.05 |

3 |

Co- |

Absent |

56 |

7.42±2.01 |

-0.461 |

1.287 |

0.203 |

>.05 |

4 |

Hernia Clinical |

Unilateral |

52 |

1.94±0.54 |

-0.577 |

-0.703 |

0.485 |

>.05 |

5 |

Hernia |

Unilateral |

52 |

1.94±0.54 |

-1.634 |

-5.763 |

0.000 |

<0.001 |

6 |

Hernia |

Left |

25 |

1.67±0.66 |

-0.600 |

-2.133 |

0.037 |

<0.05 |

7 |

Hernia |

Indirect |

60 |

1.85±0.56 |

-0.596 |

-0.663 |

0.509 |

>0.05 |

8 |

TEPP |

Unilateral |

58 |

1.91±0.35 |

-0.7436 |

2.2058 |

0.0312 |

<0.05 |

Table 3 Effect of Demographic Characteristics on Operation Time during TEPP Hernioplasty (N=68)

§OT, operation time; *SD, standard deviation; ¶CID, 95% confidence interval of the difference; **F, ANOVA value; ***t, independent-sample t-test value; BMI, body mass index; TEPP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal hernioplasty; (Reproduced with permission from Ansari’s Thesis17)

Conversion: In 3 out of 63 patients, the TEPP hernioplasty underwent early conversion to TAPP (trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal) hernioplasty (n=1), OPP (open preperitoneal) hernioplasty (n=1) and open anterior mesh hernioplasty (n=1), resulting in an overall incidence of conversion rate of 4.8%. The three cases included one patient with unilateral left hernia, second patient with unilateral right hernia and the third patient with bilateral inguinal hernia. The conversion in the three cases was secondary to the following causes: (1) In one patient, peritoneal injury occurred just after placement of the 1st optical port; the back end of the trocar was inadvertently lifted up by the assistant, resulting in the posterior movement of the trocar tip which ruptured the peritoneum with creation of frank pneumoperitoneum. Hence the procedure was converted to the TAPP when the posterior rectus sheath was found very short with a high arcuate line seen across the transparent peritoneum with a 5-mm telescope through the lateral working port; (2) In the second patient, injury to deep inferior epigastric vessels occurred just after placement of the 2nd port (first working port); the arterial injury occurred by the roughened joint of the Maryland dissector during the early single-hand surgical dissection and could not be coagulated fast enough due to low setting of the electrosurgical cautery, leading to the loss of vision. A percutaneous silk suture (1-0) on a long curved needle placed below the site of injury but proved ineffective, and therefore, the procedure was converted to the open pre-peritoneal (OPP) approach to control the bleeding and to perform the open preperitoneal mesh hernioplasty. (3) In the third patient, severe CO2 retention occurred soon after the start of the procedure, leading to the anaesthetic problem. The latter patient was found to have the co-morbidities of ASA grade III on re-taking of the history. The procedure was converted fast to the open surgery for the Lichtenstein tension-free mesh repair. The post-operative recovery was uneventful in all three patients. First patient with TAPP hernioplasty was discharged from the hospital on the second post-operative day with removal stitches on first follow-up visit on 8th day. The two patients with open repair were discharged from the hospital on 8th day after removal of stitches.

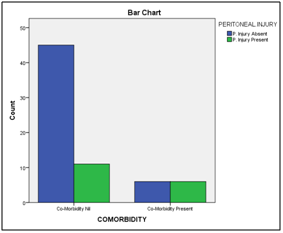

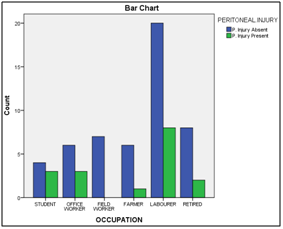

Peritoneal injury: Intra-operative peritoneal injury (PI) during the TEPP hernioplasty occurred in 17 out of 63 patients (27%). Incidence of the PI did not vary significantly with respect to the age, BMI and occupation of the patients; however, the PI tends to be significantly higher (p <0.05) in presence of co-morbidity (Table 4). Pearson Chi Square analysis also revealed a significant correlation, although Fisher’s exact test significance (2-tailed) was found insignificant (Figure 7). The incidence of the PI did not vary significantly with respect to the occupation of the patients also, although no instance of peritoneal injury was recorded in the field workers (Figure 8). The PI incidence also did not vary significantly with respect to the clinical or operative characteristics of the inguinal hernia Table 4. Early peritoneal injury by the first optical trocar forced early conversion; however, in the remainder of the patients with the peritoneal injury, continuous venting by a Veress/ hypodermic needle (#18) at Palmer point allowed completion of the procedure albeit with slightly reduced endoscopic vision and ease of procedure.

S. |

Variable |

Subgroups |

N |

P. Injury§ |

C.I.D¶ |

**F / |

Sig. |

p-value |

1 |

Age |

18-40 |

20 |

0.35 ± 0.49 |

-0.192 |

0.102 |

0.903 |

>0.05 |

2 |

BMI |

Normal |

64 |

0.27 ± 0.45 |

-0.182 |

1.185 |

0.240 |

>0.05 |

3 |

Co- |

Absent |

56 |

0.20 ± 0.40 |

-0.573 |

-2.253 |

0.028 |

<0.05 |

4 |

Hernia Clinical |

Unilateral |

52 |

0.25 ± 0.44 |

-0.465 |

-0.735 |

0.465 |

>0.05 |

5 |

Hernia |

Unilateral |

52 |

1.25 ± 0.44 |

-0.465 |

-0.735 |

0.465 |

>0.05 |

6 |

Hernia |

Left |

25 |

0.28 ± o.46 |

-0.173 |

0.430 |

0.669 |

>0.05 |

7 |

Hernia |

Indirect |

60 |

0.25 ± 0.44 |

-0.330 |

0.000 |

1.000 |

>0.05 |

8 |

TEPP |

Unilateral |

58 |

0.24 ± 0.43 |

-0.359 |

-1.748 |

0.086 |

>0.05 |

Table 4 Effect of Demographic Characteristics on Peritoneal Injury during TEPP Hernioplasty (N=68)

§P. Injury, peritoneal injury; *SD, standard deviation; ¶CID, 95% confidence interval of the difference; **F, ANOVA value; ***t, independent-sample t-test value; BMI, body mass index; TEPP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal; (Reproduced with permission from Ansari’s Thesis17)

Figure 7 Correlation between the Peritoneal Injury (PI) and the Co-Morbidity: (Pearson CHISQ CC: R = 4.857, df 1, Sig. 0.028, p <0.05; Likelihood Ratio: R=4.356, df 1, Sig. 0.037, p <0.05; Linear-by-Linear Association: R=4.786, df 1; Sig. 0.029, p <0.05; Fisher’s Exact Test: Sig.(2-tailed) 0.06, p >0.05; Sig.(1-tailed) 0.038, p <0.05).17

Figure 8 Correlation between the Peritoneal Injury (PI) and the Occupation of the Patients: (Pearson CHISQ CC: R = 4.610, df 5, Sig. 0.465, p >0.05; Likelihood Ratio: R=6.207, df 5, Sig. 0.287, p >0.05; Linear-by-Linear Association: R=0.370, df 1; Sig. 0.543, p >0.05) .17

Surgical emphysema: Incidence of the intra-operative surgical emphysema (S-Emph) in the present study was 11 out of 68 TEPP hernioplasties (16.2%). In three patients with bilateral hernia, the two sides were operated at an interval of time, and the surgical emphysema did not develop during the first operation in any patient but developed during the operation on the second side in 2 out of these three patients. In 3 patients, occurrence of surgical emphysema was apparently related to the inadvertent use of the high setting of CO2 insufflator (14mmHg) used for the laparoscopic cholecystectomy prior to the TEPP repair. The subcutaneous emphysema subsided spontaneously in 48-72 hours after surgery, and none of the patients required any surgical intervention.

S. |

Variable |

Subgroups |

N |

Emphysema |

C.I.D.¶ |

**F or |

Sig. |

p-value |

1 |

Age |

18-40 |

20 |

0.35±0.49 |

-0.03 |

0.692 |

0.505 |

>0.05 |

2 |

BMI |

Normal |

64 |

0.17±0.38 |

-0.210 |

0.898 |

0.373 |

>0.05 |

3 |

Co- |

Absent |

56 |

0.11±0.31 |

-0.534 |

-2.748 |

0.008 |

<0.01 |

4 |

Hernia Clinical |

Unilateral |

52 |

0.13±0.35 |

-0.390 |

-0.842 |

0.403 |

>0.05 |

5 |

Hernia |

Unilateral |

52 |

1.17±0.38 |

-0.375 |

-0.516 |

0.608 |

>0.05 |

6 |

Hernia |

Left |

25 |

0.20±0.41 |

-0.127 |

0.645 |

0.521 |

>0.05 |

7 |

Hernia |

Indirect |

60 |

0.17±0.38 |

-0.239 |

0.296 |

0.768 |

>0.05 |

8 |

TEPP |

Unilateral |

58 |

0.12±0.33 |

-0.6.03 |

-1.726 |

0.089 |

>0.05 |

Table 5 Effect of Demographic Characteristics on Surgical Emphysema during TEPP Hernioplasty (N=68)

*SD, standard deviation; ¶CID, 95% confidence interval of the difference; **F, ANOVA value; ***t, independent-sample t-test value; BMI, body mass index; TEPP, total extraperitoneal preperitoneal; (Reproduced with permission from Ansari’s Thesis17)

Incidence of the surgical emphysema did not vary significantly with respect to the age and BMI of the patients. However, its incidence was significantly higher (p <0.05) in presence of co-morbidity Table 5, and the Pearson Chi Square Correlation was also significant (Figure 9). The incidence of the surgical emphysema also did not vary significantly with respect to the clinical or operative characteristics of the inguinal hernia (Table 5). There was also no correlation between the incidence of the surgical emphysema and the patients’ occupation, although it was not seen at all in the students and farmers (Figure 10).

Figure 9 Correlation between the Surgical Emphysema and the Co-Morbidity: (Pearson CHISQ CC: R=6.982, df 1, Sig. 0.008, p <0.01; Likelihood Ratio: R=5.755, df 1, Sig. 0.027, p <0.05; Linear-by-Linear Association: R=6.880, df 1, Sig. 0.009, p <0.01).17

Figure 10 Correlation between the Surgical Emphysema and the Occupation: (Pearson CHISQ CC: R=4.588, df 5, Sig. 0.468, p >0.05; Likelihood Ratio: R=6.683, df 5, Sig. 0.245, p >0.05; Linear-by-Linear Association: R=0.117, df 1, Sig. 0.732, p >0.05).17

Deep inferior epigastric vessels: Early instrument injury to deep inferior epigastric vessels occurred by the roughened joint of the Maryland dissector with only one working port in placement in one patient (1.5%) leading to conversion to the open preperitoneal repair (OPR), and in another two cases (3%), these vessels were taken down inadvertently during surgical dissection on to the floor of the operating field, requiring hooking up by a transcutaneous stitch or cautery coagulation/ division.

Serious vascular/ visceral complications: No serious vascular or visceral complications occurred during the early or the late part of the study. However, in one patient in the later part of the study (43rd patient in consecutive order), overstretching and partial injury occurred to the thin genital branch of the high-branching genito-femoral nerve during dissection of a large indirect hernial sac, possibly due to an optical illusion details of which is being reported elsewhere by the author. The nerve injury resulted in mild orchalgia that took 9 months to resolve spontaneously on conservative treatment.

All patients in the present study were males. Recently Abd-Raboh9 and Hisham33 have also reported TEPP hernioplasty in only males. It seems prudent to discuss each outcome measure individually for better understanding.

Endoscopic vision: In the present study, the endoscopic vision (endovision) was found excellent, good and poor according to the visual analog score of 1-10. The mean score of the endoscopic vision was 8.20±1.33 (range 4.0-9.5), with an overall rating of excellent grade. Contrary to the common belief, the endoscopic vision was found independent of age, BMI, co-morbidity and clinical characteristics of hernia, side of operation in unilateral cases, but it was found significantly less (<0.05) on the contralateral side during the bilateral TEPP hernioplasty with 3-midline port technique Table 1. No objective study on endovision is reported in the literature. However, some investigators cited the poor endovision as a significant factor towards conversion,29,30 indicating a need for more objective studies on grading of endovision and causes of the poor endovision in order to safeguard against conversion and its related morbidity to validate the result of our small study.

Ease of procedure (EOP): Grading of the ease of a procedure (EOP) is often found challenging because of various factors including prior knowledge, competence and experience. In the present study, the mean score of the EOP (measured on a visual analog score of 1-10) for our TEPP hernioplasties was 7.27±2.05 VAS (range 4.0-9.5), suggestive of an overall rating of good grade. This is possibly reflective of the steep learning curve of the TEPP hernioplasty.2,3,6 EOP in our study was found independent of age, BMI, co-morbidity and clinical characteristics of hernia, side of operation in unilateral cases, but it was found significantly less (<0.01) on the contralateral side during the bilateral TEPP hernioplasty Table 2. No objective study on EOP is reported in the literature. The procedure was simply graded as ‘easy’ in 95% and ‘difficult’ in 5% by Misra and colleagues.30 However, some investigators suggested directly or indirectly the poor EOP as a significant factor towards conversion,11,12,29−31 indicating a need for more objective studies on grading of endovision and causes of the poor endovision in order to safeguard against conversion and its related morbidity in order to validate the observations of the present study.

Operation time (OT): Mean operation time (OT) in the present study ranged 0.75-3.25 hours with an overall mean of 1.87±0.59 hours. The operation time (OT) was not dependent on the patients’ age, BMI, co-morbidity and clinical characteristics of the hernia Table 3. However, as expected, simultaneous bilateral TEPP hernioplasty took 1.2 times greater time (p<0.05) as compared to the unilateral TEPP (Table 3). In 2008, Misra30 have reported a lower ratio of 1:1.1 both unilateral and bilateral TEPP. In 2009, Dulucq32 have lowest operating time 17±6 and 24±4 minutes for unilateral and bilateral TEPP respectively with a ratio of 1: 1.4; this may be a reflection expert use of balloon dissector. However, Dulucq’s operation times have never been duplicated in literature Tables 6 (Table 7). Recently in 2017, Hisham33 reported operation time of 99±25 min (range 70-170) which is in tune with our result of 113±44 min (range 60-205).

S. |

Outcome |

Present |

Abd-Raboh |

Hisham |

Park |

Zanella |

Shirazi |

Hamza |

Dulucq |

Misra |

Lau |

Ferzli |

Felix |

Ferzli |

1 |

Patients (N) with Primary Inguinal Hernia |

60 |

20 |

30 |

41 |

104 |

100 |

25 |

1254 |

56 |

82 |

92 |

382 |

25 |

2 |

Mean Age (Yrs) |

50±17 |

40±12 |

40±13 |

53.5 |

62±17 |

58 |

35±13 |

61±15 |

49±15 |

64±16 |

54 |

49 |

NA |

3 |

Mean BMI Mean±SD |

23±2 |

NA |

NA |

23 |

24.77¶ |

NA |

23.2±5.3 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

4 |

Operation Time One Side (Min.) Mean±SD (Range) |

113±35 |

99±25 |

99±25 |

86.7 |

50±20 |

45(30-75) |

77±43 |

17 ± 6 |

75±27¶ |

NA |

36.5¶ |

NA |

90 |

5 |

Operation Time Bilateral (Min.) Mean±SD (Range) |

138± 40 |

(NA) |

N/A |

24 ± 4 |

83±25 |

NA |

NA |

||||||

6 |

Excess CO2 Retention (%) |

1.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2.2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NA |

0 |

7 |

Peritoneal Injury (%) |

28.3 |

20.0 |

6.7 |

0 |

2.7 |

0 |

4.0 |

NA |

64.3 |

1.2 |

3.3 |

NA |

4 |

8 |

Emphysema Surgical (%) |

16.2 |

10.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

19.6 |

0 |

0 |

NA |

0 |

9 |

Conversion (%) |

4.8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1.9 |

3 |

4.0 |

1.2 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

0 |

1.8 |

4 |

10 |

Visceral Injury (%) |

0 |

0 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

Minor Vascular Injury (%) |

1.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

N/A |

0.5 |

1.9 |

0 |

0 |

NA |

0 |

12 |

Major Vascular Injury (%) |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 6 Comparative Analysis of Intraoperative Complications after TEPP Hernioplasty

Note: NA, not available

S. No. |

Study |

Operation Time |

Operation Time |

|

Mean/Mean±SD/Median |

Mean/Mean±SD/Median |

Range |

||

1 |

Present Study |

75.0±21.2 (60-205) |

75.0±21.2 |

60-205 |

2 |

Lal (2003) 11 |

75.7±31.6 |

75.7±31.6 |

NA |

3 |

Park (2015) 34 |

86.7 (45-150) |

86.7 |

(45-150) |

4 |

82 (50-135) |

82 |

50-135 |

|

4 |

Andersson (2001) 62 |

81±27º |

81±27º |

NA |

6 |

Fleming (2001) 63 |

70 (30-145) |

70 |

30-145 |

7 |

Shaikh (2013) 64 |

70±19 (30-90) |

70±19 |

(30-90) |

8 |

Bilgin (1997) 65 |

69 (25–150)^ |

69 |

25–150 |

9 |

Heikkinen 44 |

67.5 (40–88)* |

67.5 |

40–88 |

10 |

Wright (1996) 52 |

60 (53-72) |

60 |

53-72 |

11 |

Vatansev (2002) 53 |

58.6±9.7 |

58.6±9.7 |

NA |

12 |

Bostanci (1998) 46 |

58 (40-85) |

58 |

40-85 |

13 |

Decker (1998) 54 |

57.2 (38-78) |

57.2 |

38-78 |

14 |

Bringman (2003) 55 |

50 (25-150) |

50 |

25-150 |

15 |

Colak (2003) 56 |

49.7±14.1 |

49.7±14.1 |

NA |

16 |

Liem (1997) 57 |

45 (35-60) |

45 |

35-60 |

17 |

Shirazi (2012) 31 |

45 (30-75) |

45 |

30-75 |

18 |

Khoury (1998) 58 |

31.5 (5-80) |

31.5 |

5-80 |

19 |

Simmermacher (2000) 59 |

27 |

27 |

NA |

20 |

Dulucq (2009) 32 |

17 ± 6 (U/L) |

17 ± 6 (U/L) |

NA |

Table 7 Operation Time – Comparative Analysis for TEPP Hernioplasty

Note: U/L, unilateral; B/L, bilateral; NA, not available

Peritoneal injury: In the present study, the overall incidence of the peritoneal injury (PI) was 28% which is in tune with the 20% incidence reported by Abd-Raboh9 and Lal11. An incidence of 0-7% has been reported by a number of investigators.29,31,33−37 However, Misra30 reported a very high incidence of peritoneal breach/laceration in both balloon dissection group (57%) and telescopic dissection group (71%). Moreover, these investigators did not elaborate on the causes of the peritoneal injury, but possibly due to space creation in the ‘true preperitoneal plane’ just outside the parietal peritoneum instead of the ‘surgical preperitoneal plane’ between the preperitoneal fascia and the transversalis fascia as described earlier by this author.28 In recent studies, Shirazi31 and Park34 have reported zero incidence of peritoneal injury (Table 6).

Surgical emphysema: Overall incidence of the intra-operative surgical emphysema (Emph) was 18.3% in the present study, which is in agreement with that of 19.6% reported in 2008 by Misra30. Dulucq32 and Abd-Raboh9 had documented an incidence of 2% and 10% respectively. However, zero incidences have reported by a number of clinical investigators Table 6.29,31,33−38 Cause of surgical emphysema in 27.3% of our patients was apparently related to the initial high insufflation pressure but in the remainder of our patient, no obvious cause was discernible. Other investigators did not elaborate on the causation of surgical emphysema, which appears to be an area of clinical interest for study because of its frightening nature albeit innocuous to majority of the patients. In three of our patients with bilateral hernia, the two sides were operated at an interval of time, and the surgical emphysema did not develop during the first operation in any patient but developed during the operation on the second side in 2 out of these three patients. These two patients had similar anatomic disposition of posterior rectus sheath, arcuate line, transversalis fascia and preperitoneal fascia/fat on the two sides of the body. Moreover, the endovision was 8 & 9.5 VAS, the EOP was 9 & 9.5 VAS, and the OT was 1 &1.75 hours. In other words, there was no obvious anatomical cause identifiable for this strange phenomenon.

Conversion: In the present study, 3 out of 71 TEPP were converted to TAPP/Open repair, with an overall conversion rate of 4%. A similar conversion rate of 4% was reported by Cohen39 but higher conversion rates of upto 10% have been reported by some investigators.6 However, a lower conversion rate of 0.7-1.9% was documented by other investigators Table 6, Table 8.29,30,32,40 Moreover, zero conversion rates have also been reported by a number of investigators (Table 8).9,11,33,35,37

S.No. |

Study |

Total Conversion |

Reasons For Conversion |

|

N |

% |

|

||

1 |

Abd-Raboh (2018) 9 |

0/20 |

0 |

- |

2 |

Hisham (2017) 33 |

0/30 |

0 |

- |

3 |

Park (2015) 34 |

0/41 |

0 |

- |

4 |

Lal (2003) 11 |

0/25 |

0 |

- |

5 |

Ferzli (1999) 36 |

0/92 |

0 |

- |

6 |

Dulucq (2009) 32 |

11/1454 |

0.7 |

Early Phase, Complicated Hernia |

7 |

Misra (2008) 30 |

1/56 |

1.8 |

Unclear Anatomy & Peritoneal Injury |

8 |

Zanella (2015) 29 |

2/104 |

1.9 |

Unclear Anatomy, Difficult to Create Space |

9 |

Shirazi (2012) 31 |

3/100 |

3.0 |

Irreducible Hernia, |

10 |

Lau (2000) 35 |

3/82 |

3.7 |

Adhesion, Large Sac, Irreducible Hernia |

11 |

Hamza (2010) 38 |

1/25 |

4.0 |

Early Peritoneal Injury |

12 |

Ferzli (1992) 37 |

1/25 |

4 |

Peritoneal Injury |

13 |

Present Study |

3/63 |

4.8 |

Peritoneal Injury, Epigastric Vessel Injury, |

Table 8 Conversion - Comparative Analysis after TEPP Hernioplasty

Reported causes for conversion include inexperience, early phase of study, unclear anatomy, irreducible hernia, complicated hernia, peritoneal injury/ pneumoperitoneum, inability to unroll mesh, difficult to create space, adhesion, epigastric vessel injury, iliac vessel injury, bowel injury, CO2 retention Table 8. However, factors leading to these complications were often not recognized or elucidated. In the present study, the factors leading to complication responsible conversion were recognized, viz., faulty selection of patient with chronic obstructive airway disease (ASA grade III) resulting in excessive CO2 retention and haemodynamic changes (n=1), roughened joint of the Maryland dissector causing injury to the deep inferior epigastric vessels (n=1), and anatomic variation of high arcuate line with peritoneal injury by the first optical port just after its placement (n=1). We did not find any report in the literature correlating the cause of conversion with the variations of abdomino-pelvic anatomy.

Minor vascular complications: Early instrument injury to deep inferior epigastric vessels occurred in one case (1.5%) leading to conversion, and in two cases, these vessels were taken down on to the floor of the operating field, requiring hooking up by a transcutaneous stitch or cautery coagulation/division. Dulucq reported an incidence of 0.47 % of these injuries. Many investigators recorded zero incidences of these injuries (Table 6). 9,11,12,29-30,34−38

Serious vascular/visceral complications: No serious visceral or vascular complications were recorded in the present study. This is in full agreement with a number of studies reporting zero incidences for the serious visceral/vascular injuries Table 6.9,11,12,29-31,34-38 In 2009, Dulucq32 reported visceral injuries in 0.08% of cases while Hisham33 reported significant incidence of visceral injuries (12%) and iliac vein injury (3%).

Post-operative seroma: In the present study, the overall incidence of the post-operative seroma was 10% of all cases. Zanella29, Dulucq32, Lau35 and Ferzli36 have reported <5% incidence of seroma while Hisham33 and Misra30 have reported very high incidences of 21% and 41% respectively. However, it is of interest that many investigators have reported zero incidence of seroma formation Table 7.9,31,34,38

Post-operative infection: The present study recorded an infection rate of 6.7%, which did not correlate with any of the patient’s demographic characteristics and primary/secondary outcome measures. This is in tune with the 5% incidence of port-site infection reported by Abd-Raboh9. Dulucq32 has document an infection rate of 0.1% in a large series. It is of real interest that many clinical investigators have reported zero incidence of postoperative infection (Table 9). 29−36, 38

S. |

Outcome |

Present |

Abd-Raboh |

Hisham |

Park |

Zanella |

Shirazi |

Hamza |

Dulucq |

Misra |

Lau |

Ferzli |

Felix |

Ferzli |

1 |

Overall Postoperative Morbidity (%) |

28.7 |

10.0 |

26.6 |

9.7 |

5.8¶ |

3.9 |

|

2.9 |

62.5 |

7.3 |

0 |

NA |

0 |

2 |

Scrotal Oedema (%) |

0 |

5.0 |

0 |

9.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NA |

17.8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

Haematoma/Seroma (%) |

10.3 |

0 |

20.6 |

0 |

2.9 |

0 |

0 |

2.1 |

41 |

4.9 |

1.1 |

10 |

0 |

4 |

Infection Port-site (%) |

6.7 |

5.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NA |

0 |

5 |

Hospital Stay (Day) |

3.3±1.7 |

1.4±0.7 |

1.4±0.6 |

3.4 |

NA |

NA |

1.04±1.0 |

1.5±0.4 |

1.2±0.6 |

2±1 |

NA |

NA |

<1 |

6 |

Significant Pain (VAS 4-6) 30-Day (%) |

5.0 |

NA |

NA |

0 |

2.9 |

0.9 |

NA |

NA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+nt |

0 |

Table 9 Comparative Analysis of Early Postoperative Complications after TEPP Hernioplasty

Note: NA, not available

Post-operative chronic pain: Incidence of the chronic inguinodynia was 1.5% in our study, which also did not correlate with any of the patient’s demographic characteristics and primary or secondary outcome measures. The incidence 1-16% is reported in literature.11,41 Dulucq32 reported an incidence of only 0.2% in a large series of laparoscopic hernioplasty Table 7.

Hernia recurrence: No instance of hernia recurrence was recorded in the mean follow-up period of 33±s.d 17 months (range 5-61 months) in the present study. No recurrence was documented in the continued follow-up for 43 months beyond the study period. Our result in full agreement with those of many investigators who also reported zero recurrence (Table 10) Table 11.9,11,30,33,34,36,37,42−48 Faure2 reported a recurrence rate of 0.5% after TEPP hernioplasty. Dulucq32 reported 2.5% while Shirazi31 and Hamza38 reported 4% incidence of hernia recurrence Table 8 (Table 11). Presently zero-recurrence rate is cherished by the many TEPP surgeons, especially in the surgical forums and live operative workshops.

S. |

Outcome |

Present |

Abd-Raboh |

Hisham |

Park |

Zanella |

Shirazi |

Hamza |

Dulucq |

Misra |

Lau |

Ferzli |

Felix |

Ferzli |

1 |

Recurrence (Overall) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NA |

3.9 |

4.0 |

2.5 |

0 |

NA |

0 |

0.3 |

0 |

2 |

Study Follow-Up |

33.1±16.9 |

7.6±2.1 |

7.1±2.2 |

23.2 |

NA |

14-17 |

6 |

NA |

24 |

NA |

12 |

NA |

0 |

3 |

Extended Follow-Up |

76.1±16.9 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

0 |

Table 10 Comparative Analysis of Follow Up and Hernia Recurrence after TEPP Hernioplasty

Note: NA, not available

Correlations: The endoscopic vision had a significant direct correlation with the ease of procedure (EOP) and a significant inverse correlation with the operation time (OT) and the surgical emphysema. The endovision did not have any significant correlation with any other secondary outcome measure (SOM). In addition to the endovision, the EOP had a significant but inverse correlation with the OT, the peritoneal injury and the surgical emphysema. In addition to the endovision and EOP, the OT correlated directly with the incidence of the peritoneal injury (PI). Apart from the EOP and the OT, the PI did not have any significant correlation with any other secondary outcome measure (SOM). Apart from the endovision and EOP, the surgical emphysema did not have a significant correlation with any other SOM. The incidence of seroma, infection and chronic inguinodynia did not correlate with any of the secondary outcome measures in the present study. To the best our knowledge, such correlations have not yet been reported in literature.

S. No. |

Study |

Follow-Up |

Recurrence after TEP |

Recurrence after Open |

1 |

Present Study |

76.1±16.9 |

0/60 |

0/2000 (Unpublished) |

2 |

Lal (2003) 11 |

13 |

0/25 |

0/25 |

3 |

Heikkinen (1998) 44 |

NA |

0/22 |

0/23 |

4 |

Bostanci (1998) 46 |

NA |

0/32 |

0/32 |

5 |

Merello (1997) 45 |

NA |

0/60 |

0/60 |

6 |

Stoker (1994) 47 |

7 |

0/75 |

0/75 |

7 |

Champault (1994) 48 |

12 |

0/92 |

0/89 |

8 |

Abd-Raboh (2018) 9 |

7.6±2.1 |

0/20 |

NA |

9 |

Hisham (2017) 33 |

7.1±2.2 |

0/30 |

NA |

10 |

Park (2015) 34 |

23.2 |

0/41 |

NA |

11 |

Misra (2008) 30 |

24 |

0/56 |

NA |

12 |

Ferzli (1999) 36 |

12 |

0/92 |

NA |

13 |

Fitzgibbons (1995) 43 |

23 |

0/87 |

NA |

14 |

Phillips (1995) 42 |

22 |

0/578 |

0/286 |

15 |

Ferzli (1992) 37 |

6 |

0/25 |

NA |

Table 11 Recurrence after TEPP – Comparative Analysis after TEPP Hernioplasty

Note: NA, not available

To conclude, the present study documented absence of major vascular/visceral complications, which is in full agreement with several other studies reported in literature.9,11,12,29-31,34−38 Present study also recorded absence of hernia recurrence, which is in full agreement with many other.9,11,30,33,34,36,37,42−48 A number of clinical studies have reported zero incidences of conversion9,11,33,34,36, minor vascular injury9,11,33,34,36, surgical emphysema 29,31,33,34−37, peritoneal injury31,34, excessive CO2 retention9,30-38, infection29-31,33−36,38, Seroma9,31,34,38, scrotal oedema29,31,33,38, neuralgia.9,12,29-31,34−38 Laparoscopic hernia surgery has been criticized because of its complexity, high costs, risk of major complications, and need for general anesthesia49. Minimization of complications and recurrences are possible through adequate surgeon’s training and proctoring, proper patient selection and optimization of surgical technique.49,50 Complications, mostly minor in nature, gradually diminish with increasing experience of the laparoscopic hernia surgeon.51 Therefore, it cannot be overemphasized that ‘zero accident vision’ is attainable for the laparoscopic TEPP hernioplasty with sound anatomical knowledge, preparation, proper training and proctoring, well-defined choreographic surgical technique and experience. ‘Zero accident vision’ is attainable with acceptable operation time similar to the open repair as many investigators reported an operation time ≤1 hour 31,32,52−59 to ≤1.5 hour.11,34,44,60−65 Fitzgibbons and Puri66 concluded that factors safeguarding against recurrence of hernia after laparoscopic hernioplasty include surgeons’ satisfactory experience, adequate dissection, sufficient prosthesis size and overlap of hernial defects, proper fixation, absence of prosthesis folding or twisting, absence of missed hernias, or absence of hematoma/seroma lifting the mesh.

It would not out place to mention the limitations of the present study. Our study had two obvious limitations. Firstly, the number of patients recruited for TEPP hernioplasty is rather small; the reasons may include single surgeon’s study (only one out of six surgical units), public apprehension about the newer approaches of the modern laparoscopic technique, higher cost, long learning curve, longer operating time as compared to open or TAPP (transabdominal preperitoneal) repair, consultant-only technique at least in most teaching institutions, demanding technique of and peer reluctance for TEPP as compared to TAPP for modern easy-going surgeons both young and senior alike, need of training surgical residents through the so-called straightforward open repair (Lichtenstein’s/ Bassini’s repair).

Present study documented zero incidences of major vascular/visceral complications and long-term recurrence. Minor complications included inferior epigastric vessel injury (1.5%), excessive CO2 retention (1.5%), surgical emphysema (16.2%), and peritoneal injury (28.3%), port-site infection (6.7%), Seroma (10.3%), temporary orchalgia (1.5%). Conversion rate was 4.8%, and average hospital stay was 3.3 days. The philosophy of ‘zero accident vision’ is potentially possible and attainable with mastery of TEPP hernioplasty technique and dedicated motivation as a large number of clinical investigators have reported zero incidences even for the various minor intraoperative and postoperative complications, in addition to the zero rates of the major complications and hernia recurrence.

All figures and graphs of this article are reproduced with permission from ‘Ansari MM. A Study of Laparoscopic Surgical Anatomy of Infraumbilical Posterior Rectus Sheath, Fascia Transversalis & Pre-Peritoneal Fat/Fascia during TEPP Mesh Hernioplasty For Inguinal Hernia: Doctoral Thesis/Dissertation for award of degree of PhD (Surgery) to the author, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India, 2016.’

None.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.