MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6162

Background: In this study, the advantages of a newly developed method of reconstruction following laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy were confirmed in patients with squamous cell carcinoma originating from the pharyngo-esophageal junction or with synchronously developed cancers of the hypopharynx and esophagus.

Methods: Between 2003 and 2014, 11patients underwent laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy at our institution. Eight patients had cancers simultaneously involving both the hypopharynx and the esophagus, two had carcinoma at the pharyngo-esophageal junction, and one had synchronously developed cancers of the hypopharynx, esophagus, and stomach. The prognosis and quality of life of these 11patients were analyzed retrospectively, to establish the utility of a newly developed, improved (supercharged) method of reconstruction.

Results:The mean operation time was 990min (range: 635-1,320min) and mean intraoperative blood loss was 1,236ml (range: 240–2,500ml). Operative morbidity, mortality, and 5-year survival rate were 45.5%, 9.1%, and 45.5%, respectively. Four patients underwent a traditional end-to-end anastomosis of the nasopharynx with the gastric tube. In all four patients, necrosis of the distal end of the gastric tube necessitated a skin flap reconstruction. One patient died from this complication. The supercharge method of reconstruction was performed in seven patients: in two using a reversed gastric tube, in four with a free jejunal graft, and in one with an ileocolic graft. None of these patients developed anastomotic leakage.

Conclusion:The supercharged method yields improved reconstruction results in patients requiring laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy. Among the advantages of this method is better quality of life for these patients.

Keywords: laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy, pharyngo-esophageal junction, squamous cell carcinoma, synchronous cancers of the hypopharynx and esophagus

Despite the recent availability of surgical treatment for hypopharyngeal cancer,1 several features of the disease pose surgical challenges. Moreover, because hypopharyngeal cancer readily invades the esophagus,2 almost 20% of patients with hypopharyngeal cancer develop synchronous esophageal cancer.3,4Most patients are diagnosed with relatively late-stage disease, with high rates of regional and distant metastasis.5 In patients with cancer originating from the pharyngo-esophageal junction or in those with synchronous hypopharyngeal and esophageal cancers, laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy is the preferred surgical approach. However, this operation is technically challenging for many surgeons. Furthermore, because of the malignant features of hypopharyngeal cancer and high incidence of gastric tube necrosis followed by major anastomotic leakage, these patients have high perioperative morbidity and survival is poor. The aim of this study was to confirm the advantages of an improved method of reconstruction after laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy in patients with hypopharyngeal and synchronous hypopharyngeal and esophageal cancers.

Between 2003 and 2014, 11patients underwent laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy at our institution. Eight patients had synchronous cancers of the hypopharynx and esophagus, two had carcinoma of the pharyngo-esophageal junction, and one had synchronously developed cancers of the hypopharynx, esophagus, and stomach. The patient’s records, operative notes, histopathology reports, and imaging studies were reviewed retrospectively. Tumor location, size, and esophageal invasion were diagnosed endoscopically. Enhanced computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging were used in the detection of distant metastasis. The average age of the 11patients (ten males and one female) was 69.6years (range: 54-79years). Eight patients had been treated with preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for hypopharyngeal and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. All patients provided written informed consent. They were followed at our institution until March 2015. Operation time, intraoperative blood loss, starting postoperative date of solid-food ingestion, postoperative hospital stay, and survival were analyzed. Differences between two parameters were compared using χ2 tests for independence, Fisher’s exact probability test, and the Mann-Whitney U test. The survival curves of the patients were generated using a Kaplan-Meier method.

Patient survival

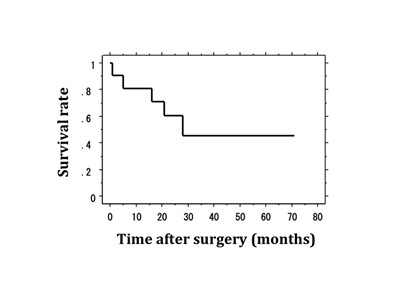

The demographic details of the 11patients are shown in (Table 1). The mean operation time was 990min (range: 635-1,320min). Mean intraoperative blood loss was 1,236ml (range: 240-2,500ml). Postoperative complications were detected in five patients, one of whom died from an operative complication. Operative morbidity, mortality, and the 5-year survival rate were 45.5%, 9.1%, and 45.5%, respectively (Figure 1). In the ten surviving patients, solid-food ingestion was resumed after 27 postoperative days (range: 10-62days). The average postoperative hospital stay was 72.7days (range: 31-242days).

Patient |

Age/Sex |

Diagnosis |

Reconstruction and anastomosis |

Supercharge |

Operation time (min) |

Intraoperative bleeding (ml) |

Morbidity |

1 |

79/M |

Hypopharyngeal and esophageal double cancers |

Pharyngo-gastric tube |

No |

1,200 |

2,500 |

Gastric tube necrosis |

2 |

77/M |

Hypopharyngeal and esophageal double cancers |

Pharyngo-gastric tube |

No |

1,320 |

2,500 |

Gastric tube necrosis |

3 |

71/M |

Hypopharyngeal and esophageal double cancers |

Pharyngo-free jejunal graft-gastric tube |

Yes |

1,305 |

1,310 |

No |

4 |

66/M |

Hypopharyngeal and esophageal double cancers |

Pharyngo-free jejunal graft-gastric tube |

Yes |

1,127 |

1,385 |

Pneumonia |

5 |

71/M |

Hypopharyngeal and esophageal double cancers |

Pharyngo-gastric tube |

No |

833 |

240 |

Gastric tube necrosis |

6 |

70/M |

Hypopharyngeal, esophageal, and gastric cancers |

Pharyngo-ileocolic interposition |

Yes |

984 |

2,250 |

No |

7 |

74/M |

Hypopharyngeal and esophageal double cancers |

Pharyngo-free jejunal graft-gastric tube |

Yes |

831 |

460 |

No |

8 |

54/F |

Carcinoma at pharyngo-esophageal junction |

Pharyngo-reversed gastric tube |

Yes |

813 |

1006 |

No |

9 |

71/M |

Hypopharyngeal and esophageal double cancers |

Pharyngo-reversed gastric tube |

Yes |

805 |

725 |

No |

10 |

75/M |

Carcinoma at pharyngo-esophageal junction |

Pharyngo-gastric tube |

No |

625 |

740 |

Gastric tube necrosis |

11 |

58/M |

Hypopharyngeal and esophageal double cancers |

Pharyngo-free jejunal graft-gastric tube |

Yes |

1051 |

680 |

No |

Table 1 The demographic details of the 11 patients with hypopharyngeal cancer invading the esophagus or hypopharynx or synchronous laryngeal and esophageal cancers. F: Female; M: Male

Reconstruction without the supercharge method

Four patients underwent replacement of the pharynx and entire esophagus with a narrow gastric tube from along the greater curvature of the stomach. The use of a narrow gastric tube and preservation of the right gastric and right gastroepiploic vessels comprise the typical approach in reconstruction after esophagectomy. The gastric tube was pulled up via a mediastinal route to the nasopharynx, without supplementary revascularization. Insertion of the tube was followed by its end-to-end anastomosis with the nasopharynx. However, in these four patients, necrosis of the distal end of the gastric tube and anastomotic leakage occurred, necessitating a repair with skin grafts. One patient died from this complication. In the three remaining patients, the ingestion of solid food was resumed after 49 postoperative days (range: 27-62days). The average postoperative hospital stay prolonged to 86.3days (range: 59–119days).

Reconstruction with the supercharge method

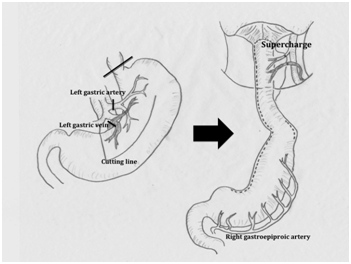

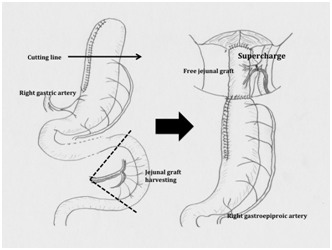

A microvascular anastomosis (supercharge) was performed in seven patients at reconstruction. In the patient with synchronous cancers of the hypopharynx, esophagus, and stomach, after resection of the larynx, pharynx, esophagus, and stomach, the right side of the ileal colon, including the preserved middle colic vessels, was pulled up to the pharynx via an antesternal route. At the same time, the ileocolic artery and vein were anastomosed to the superior thyroid artery and external jugular vein, respectively. In two patients (one with advanced carcinoma at the pharyngo-esophageal junction and the other with synchronous advanced hypopharyngeal and early esophageal cancers), a reversed gastric tube was established. After resection of the larynx, pharynx, and esophagus, the left gastric vessels were dissected and the stapling instrument was placed at the secondary branch of the left gastric artery, at a right angle to the lesser curvature of the stomach (Figure 2). The reversed narrow gastric tube was pulled up to the nasopharynx through the mediastinum. The left gastric vessels were anastomosed to the superior thyroid artery and external jugular vein microscopically (Figure 2). A free jejunal graft was used in the remaining four patients with synchronous advanced hypopharyngeal cancer and esophageal cancer. After preparation of the narrow gastric tube, a jejunal graft of ~20cm was harvested, dissecting the jejunal vessels as close as possible to the superior mesenteric vessels. The narrow gastric tube was pulled up to the nasopharynx through the mediastinum followed by removal of ~10cm of the distal end of the tube. Microanastomosis of the jejunal vessels with the superior thyroid artery and external jugular vein was followed by an end-to end-anastomosis between the nasopharynx-jejunal graft-and the gastric tube (Figure 3). Postoperative pneumonia developed in one of the seven patients (complication rate of 14.3%). The postoperative hospital stay of this patient was 242days. In the other six patients, the average starting day of solid-food ingestion and the postoperative hospital stay were 19days (range: 10-29days) and 37.7days (range: 31-53days). Notably, none of these seven patients who underwent the supercharged anastomosis procedure developed necrosis or anastomotic leakage.

Comparison the operative outcomes between the reconstructions with and without the supercharge method

The operative outcomes (operation time, intraoperative blood loss, morbidity, and mortality) were compared between the two operation methods (with and without supercharge). No significant difference was detected in operation time and intraoperative blood loss between the groups. But, postoperative complication highly occurred in the without supercharge group (Table 2).

Figure 3 Free jejunal graft method: The narrow gastric tube is prepared. The right gastric and right gastroepiploic vessels are preserved. A jejunal graft approximately 20 cm in length is harvested, dissecting the jejunal vessels as close as possible to the superior mesenteric vessels. The gastric tube is pulled up to the nasopharynx through the mediastinum, followed by the removal of ~10 cm of the distal end of the gastric tube. The plastic surgeon establishes an anastomosis between the jejunal graft vessels and the neck vessels microscopically. An end-to-end anastomosis between the nasopharynx and the jejunal graft-gastric tube is created.

|

Without the supercharge method |

With the supercharge method |

P |

N |

4 |

7 |

|

Mean operation time (min) |

994.5 |

1014.2 |

0.831 |

Mean intraoperative bleeding (ml) |

1445 |

1226 |

0.67 |

Morbidity |

4 (100%) |

1 (14.3%) |

0.006 |

Mortality |

1 (25%) |

0 |

0.165 |

Table 2 Comparison the operative outcomes between the reconstructions with and without the supercharge method

In patients with malignancies treated by surgical resection of the larynx, pharynx, and esophagus, reconstruction requires a long graft. After total thoracic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer, reconstruction typically involves the stomach and the placement of a narrow gastric tube.6 However, pulling up this narrow gastric tube is difficult. If graft necrosis develops, anastomotic leakage or mediastinitis is nearly inevitable. This complication is often fatal. In this study, traditional reconstruction using a narrow gastric tube was performed in four patients. The tubes were long enough to reach the nasopharynx and no tube abnormalities were recognized visually at the time of the operation. Nonetheless, in all four patients necrosis of the distal end of the gastric tubes developed by postoperative day4. Ischemia at the distal end of a narrow gastric tube is often progressive. Our supercharged anastomosis minimizes the risk of tube necrosis, by increasing the vascularization of the reconstructed region. Murakami et al.7 reported that an additional vascular anastomosis between the short gastric vessels and the vessels of the neck reduced the risk of graft necrosis. However, supercharged anastomosis between the short gastric vessels of the narrow gastric tube and the vessels in the neck may be difficult.8

The advantages of a reversed gastric tube in reconstruction after laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy were described by Huang et al.4 who performed a microanastomosis between the preserved left gastric vessels and the vessels in the neck. The left gastric vessels provide donor blood vessels of adequate size and diameter, thus improving the vessel anastomosis. We used this technique in two patients (one with advanced carcinoma at the pharyngo-esophageal junction and one with synchronous advanced hypopharyngeal and early esophageal cancers). This procedure yielded favorable results, including no anastomotic leakage or complications. However, with this method, we could not dissect the right and left pericardial lymph nodes nor the lymph nodes along the lesser curvature of the stomach. In patients with advanced esophageal cancer, dissection of the abdominal lymph nodes is essential to prolong survival.9–11 Thus, the benefits of this reverse gastric tube method may be limited to patients with carcinoma at the pharyngo-esophageal junction or synchronous hypopharyngeal and early esophageal cancers.

Our supercharged method can be used for reconstructions in patients with synchronous hypopharyngeal cancer and advanced esophageal cancer. It involves the introduction of a narrow gastric tube plus a free jejunal graft. The pericardial lymph nodes and the lymph nodes along the lesser curvature of the stomach could be dissected completely. During the procedure, ~10cm of the distal end of the narrow gastric tube should be removed, to allow the distribution of blood, supplied by the right gastric and right gastroepiploic arteries, to the entire length of the tube. This reconstruction method was performed in four patients. Although one patient developed postoperative pneumonia, in none of the four patients treated by the supercharged method were there problems involving the anastomosis. In supercharged anastomosis, the occurrence of thrombus at the microvascular anastomosis may be fetal. The short gastric vessels of the narrow gastric tube are too small for supercharge. Thus, we selected enough size of vessels such as left gastric vessels or jejunal vessels.

By using a microvascular anastomosis that provides additional perfusion of the graft, the supercharged method can prevent serious complications such as graft necrosis. The microsurgery technique also allows the creation of a longer conduit for replacement of the entire esophagus and hypopharynx. Despite the small number of patients in this study, the low failure rate, low mortality and short hospitalization time strongly suggest that the supercharged method is a safe, reliable, and promising reconstruction procedure for use in patients requiring laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy.

We thank Dr. Bin Nakayama for performing the microvascular anastomoses.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.