MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 2

1Department of Leadership & Health Sciences, University of Central Arkansas, USA

2Department of Health Sciences, University of Central Arkansas, USA

3Department of Leadership, University of Central Arkansas, USA

4Department of Communication Disorders, Arkansas State University, USA

5Extension Office, University of Arkansas, USA

Correspondence: Department of Leadership & Health Sciences, University of Central Arkansas, USA, Tel 501-336-4340

Received: January 18, 2020 | Published: April 9, 2020

Citation: Lane E, Morris D, McClellan R, et al. Public health leadership in a disadvantaged landscape. MOJ Public Health. 2020;9(2):44-51. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2020.09.00323

Objectives: To explore how Arkansas public health leaders (PHLs) and resident participants (RPs) within the Delta perceive well-being and how PHLs address wicked well-being disadvantages.

Methods: GIS mapping and Country Health Rankings data were used to identify areas with high levels of health disparities and social, economic, and environmental disadvantages within the Arkansas Delta. PHLs and RPs were interviewed to determine how services aligned with measured health disparities and social, economic, and environmental disadvantages.

Results: Delta PHLs focused on health behavior change and clinical care, despite reporting that social, economic, and environmental challenges thwart efforts. They enlisted cross-sector collaborations to address health disparities but not for social, economic, and environmental disadvantages. Delta RPs reported that health services are adequate, but limited, and most RPs have little awareness, means, or motivation to access services and do not understand the importance of their health. Both PHLs and RPs commented well-being is rooted in deeper social, economic, and environmental issues.

Conclusions: Overall, PHLs and RPs recognize the availability of basic health services, yet realize these services alone are inadequate in shaping well-being. Changing health disparities in the Delta may require PHLs and other stakeholders at the state level and in the policy arena to enlist cross-sector collaborations to target wicked social, economic, and environmental disadvantages to well-being.

Keywords: well-being, public health, disparities, cross-sector collaboration, leadership

Social and ecological approaches to understanding and addressing health illustrate that health status is contingent upon more than individual health behaviors; rather, health status sits at the intersection of genetic makeup, health behaviors, clinical care, and social, economic and environmental conditions, like adequacy of housing and education.1–3 Additionally, a review of research from the World Health Organization, federal health agencies, and scholars in public health and medicine noted that approximately 70% of variance in health status is accounted for by social, economic, and environmental conditions, while only 30% of variance is accounted for through genes, health behaviors, and clinical care.4 Accordingly, achieving good health status requires appropriate attention and priority to various social, economic, and environmental determinants of well-being. A failure to recognize the influence of these well-being determinants and not prioritize this view of health, is short sighted and contributes to well-being disadvantages.4– 9 This negatively affect a person’s ability to achieve what he or she values, and creates a lack of genuine opportunity for secure functioning of human capabilities.10,11 Additionally, the failure of well-being is rooted in the complexity of public health problems which are messy, intertwined and wicked in nature.5–7,9 They are difficult to frame, highly uncertain, and offer no clear or easy solutions.12–14 Wicked well-being disadvantages are complex social, economic, and environmental problems, which contribute to intersectional health disparities.15,16 Areas facing these disadvantages can experience a higher prevalence of food deserts, lower access to healthcare and public health services, poor water quality, and low household income.

A disadvantaged landscape: The Arkansas Delta

The Arkansas Delta is an exemplar of a disadvantaged landscape. The region encompasses a rich agricultural area of the Mississippi River basin along the state’s eastern border. Data on life expectancy in Arkansas show a clear disparity between those living in the Delta and those living in other areas of the state. According to the Arkansas Department of Health’s Red County Report,17 10 counties in the state have a life expectancy of 74 years or less, compared to the national average of 78.8 years. Seven of the 10 red counties are situated in the Delta. Beyond disparities of life expectancy, secondary data indicate that the Delta is home to poor educational attainment, low income, inadequate housing, violent crime, and other social, economic, and environmental disadvantages.18 In one Delta county, 30% of adults have less than a high school education, median earnings are approximately $20,000 a year, and 70% of children under age six live in poverty.17 The Arkansas Delta is a wicked disadvantaged landscape where multiple health, social, economic, and environmental disadvantages intersect.10,15,16 Public health leaders (PHLs) focused on the Arkansas Delta face wicked well-being disadvantages.

What are PHLs to do in these highly disadvantaged landscapes? How do PHLs address wicked well-being disadvantages? These questions call upon PHLs to explore ways of leading that attend to overall well-being, thus thwarting wicked disadvantage. Recently, public health literature has prompted leaders to collaborate across public, nonprofit, and private sectors as a “capability to secure a society that places health and wellness above profit and private interests…, solving health inequity and improving health of millions in the United States”.6,7,13,19–25 Cross-sector collaboration may offer an appropriate leadership approach as it emphasizes that complex public problems cannot be addressed in isolation of a single sector (like healthcare) and notes the priority of bringing together multiple sectors to target wicked disadvantage, initiating social change and enhancing overall well-being.6,7,13,19, 24–27 Further, public health research calls for a reevaluation of leadership in order to understand public health work across systems and with multiple partners across sectors to address wider determinants of health.19,23 Given the call for leadership research and the landscape of wicked well-being disadvantage in the Arkansas Delta, this study explored how Arkansas PHLs and Delta residents perceive well-being and how PHLs address wicked well-being disadvantages.

A sequential, three-phase, multimethod qualitative case study was conducted in an attempt to understand PHLs’ and Delta resident participants’ (RPs’) perceptions of well-being and attempts by PHLs to address wicked well-being disadvantages in the Delta.28 Phase I involved a review of existing County Health Rankings (CHR) data to determine what counties within the Delta faced the most disadvantage. Geographic information systems (GIS) and mapping was used to illustrate well-being disadvantages across counties. Before pursuing interview data from PHLs and RPs in Phase II, IRB approval was granted. Signed consent was petitioned and acquired from all interview participants. Confidentiality was assured. In Phase II of data collection, PHLs were interviewed to acquire their perceptions of well-being in the area and to learn of their services provided toward addressing well-being challenges. These data were complemented with interview data from RPs. In Phase III, CHR data identified which health disparity indicators were most prevalent in the study area and was compared to these indicators and services described by PHLs.

Phase I: Arkansas health ranking data

Secondary CHR data was compiled from the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.29 Out of 36 possible health factor and health outcome indicators, 19 indicators most relevant to well-being were selected. Statistically significant z-scores demonstrated that 17 of these represented the greatest health disparities in the region. Two additional indicators were chosen because other national and local data as well as public health literature illustrated the importance of insurance rates and access to exercise to overall well-being.18,30–35 These indicators became the benchmark for assessing well-being in the Delta. Standardized z-scores with values greater than zero represented greater disadvantage and values less than zero represented greater well-being. These scores were aggregated across 17 Delta counties, and maps were generated to visualize the data and identify areas of wicked well-being disadvantage.

Phase II: Interviews of public health leaders and delta residents

Web searches of formal and informal public health organizations (e.g: state and local health and cooperative extension agencies, nonprofits, and grassroots groups) and snowball sampling provided a list of PHLs in the region. Face-to-face interviews with PHLs explored how these leaders conceptualize well-being, portray their efforts to address well-being, and address wicked well-being disadvantage in the Delta. Open-ended questions facilitated and guided discussions with PHLs, beginning with a series of introductory questions including inquiries about the main objectives of their programs, funding sources secured, and program recipients’ location and needs. A series of key questions were asked to dive more deeply into how PHLs perceive well-being and the processes and strategies they use to address wicked well-being disadvantages. PHLs provided contact information for program participants, and RPs were then interviewed to explore how PHLs’ efforts compared with RPs’ perceived need.

PHL and RP transcripts were coded through open and axial coding, pinpointing significant and recurring aspects of participants’ comments.36,37 Each researcher independently read and selected their own significant passages. The research team collectively discussed the analyses, identifying common passages that the majority believed were significant. This “multiticoding process” secured a qualitative “interrater reliability” and “intercoding.”38,40 The transcripts from the PHLs were analyzed first to ascertain how they described well-being in the Delta and their efforts toward improving it. The same procedure was followed for the RPs. From the coding process and analysis, three themes emerged.

Phase III: Further investigation of phls initiatives and need in the delta

In Phase III, CHR data was used to determine which of the indicators were most prevalent in contributing to overall health disparities in the region. These most prevalent health disparities (MPHD) highlighted wicked well-being disadvantages in the Delta. The MPHD were compared to PHLs’ reported efforts to address well-being. The results of this investigation are presented in the following section.

The CHR data and analysis of z-scores revealed an eight-county area (St. Francis, Monroe, Desha, Lee, Chicot, Crittenden, Mississippi, and Phillips) that represented the most disadvantaged region within the Delta. A GIS map was developed using these data (Figure 1). These counties faced a greater number of well-being disadvantages and therefore became the focus of the qualitative analysis.

Figure 1 Composite Z-scores by Delta County.

Note: Countries in the study area are indicated with an asterisk. Counties with higher aggregate z-scores represent areas with more well-being disadvantages. Counties with lower aggregate z-scores represent areas with less well-being disadvantages.

Interviews with public health leaders

The interview participants included 26 PHLs who provided services in the Delta and who were from the following health agencies and organizations:

From the qualitative analysis of PHLs’ comments, passages were sorted, categorized, and collapsed into three prominent themes:

From these themes, and with the use of specific excerpts, perspectives of Delta PHLs and their efforts toward addressing well-being in the Delta were portrayed.

All of the PHLs acknowledged that health services should be rooted in an assessment of community data. They recognized the technical competence of aligning need with service. Often, PHLs noted the importance of identifying needs of program recipients and engaging community members in needs assessments. The majority of the PHLs remarked that going to the residents meant also getting to know them. They pointed out that relationships were key in improving health in the Delta. PHLs described needs assessment as a necessary tool to work for and with communities. Upon assessing needs of the community, PHLs noted that their efforts must be consistent, sustainable, and collaborative. Eleven of the participants described the utility of partnerships and collaborations. Participants emphasized how collaborations allow them to maximize funding and other resources and make a larger impact on those they serve. PHLs expressed the importance of collaboration and described the need to emphasize collaboration with partners whose efforts go beyond targeting health behaviors to get at social, economic, and environmental change. PHLs may recognize the need to work not only from a multi-sectoral approach but also need to target social, economic, and environmental factors. Despite the PHLs’ emphases on getting to know residents and their situations, despite their recognition that meaningful collaborations require strong multi-sessional and multi-sectoral approaches (which include assessing needs, strategic planning, and collaboration to address health challenges), PHL participants often commented that these efforts alone do not get at the root of problems in the Delta region. Generally, the PHLs expressed a genuine concern for the people they serve, noting the challenges that residents face living in a wicked disadvantaged landscape, where multiple social, economic, and environmental problems persist.

Interviews with residents

From the invitation to participate in interviews, fifteen individual RPs agreed to participate in one-on-one interviews. Participants included a long-time city official, two school administrators, two local artists, and 10 other residents who attended a local health fair. The analysis of residents’ interviews was approached in the same manner as the PHLs’ interviews. From the qualitative analysis of RPs’ comments, two prominent themes emerged:

Participants discussed the effectiveness of services offered by health providers in the Delta, and had a mixed response. Most RPs described services as effective, yet outlined a number of barriers to overall effectiveness. In large part, RPs depicted health services as being effective for routine health problems, but more specialized health services were limited, out of reach, and could only be accessed outside of the Delta. Compounding the challenge of a lack of specialized services in the Delta, some residents reiterated the challenge of access to transportation for those needing these services. Some RPs noted that a few health clinics provided transportation for people who need to travel outside the Delta. However, this transportation service was inconvenient and may have exacerbated certain health problems. Further, some RPs mentioned other barriers to effective health services including general unawareness of services, high crime rates that made it difficult to exercise or play outdoors, little motivation to change health behaviors, and a reactionary rather than proactive perspective about health. In accordance with PHLs, RPs described a myriad of challenges in the Delta, indicating the difficulty of making good choices about one’s health while living in a wicked disadvantaged landscape. These comments echoed what was heard from PHLs. Improving health and well-being requires more than health education, outreach, and multi-sectoral collaboration to simply provide general health services. Some RPs also offered solutions to well-being challenges that reiterate the importance of economic, social, and environmental factors.

Phase III: results: comparing phls’ efforts with most prevalent health disparities

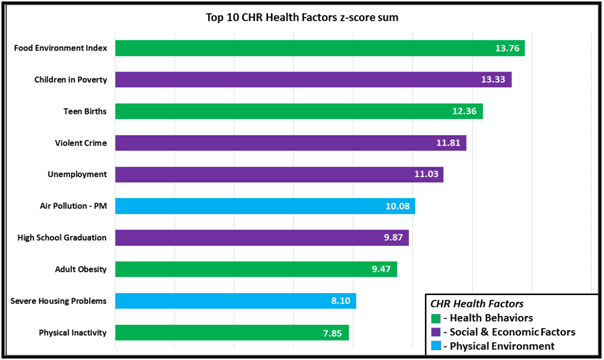

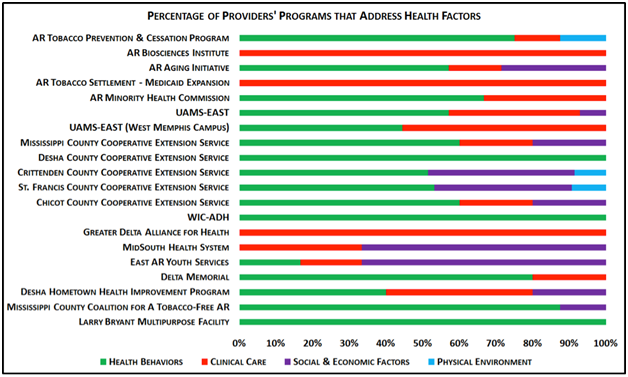

When PHLs described how they addressed well-being needs, types of programs and efforts were mentioned. These types of programs were categorized according to the four categories of CHR health factors: health behaviors, clinical care, social and economic factors, and physical environment. These categorized efforts were cross-analyzed with existing health disparity. Findings illustrate the most prevalent health disparities (MPHD) in the region (Figure 2) and how health providers’ programs are targeting these disparities (Figure 3). The MPHD were identified by comparing scores between the four categories of CHR health factors mentioned above. Figure 2 shows the Top 10 CHR health factors scores out of the original indicators used to determine the most disadvantaged counties in the Delta. The Top 10 scores are considered the MPHD. Out of the MPHD, four fall under social and economic factors, four fall under health behaviors, and two fall under the physical environment. None of the MPHD falls under clinical care. These data indicate the greatest area of need in improving Delta well-being is within social, economic, and environmental factors as well as health-related behaviors. These numbers indicate the presence of complex social challenges at the core of Delta health disparities and are consistent with what PHLs and RPs reported in interviews.

Figure 2 Most Prevalent Health Disparities: Top 10 CHR Health Factors z-score sum.

MPHD Bar Chart. Sums of z-scores of CHR health factors in three categories are provided: health behaviors, social and economic factors, and physical environment. The chart shows the Top 10 z-score sums.

Figure 3 Percentage of Providers’ Programs that Address Health Factors.

Health Programs Bar Chart. Chart shows the percentage of health providers’ programs that address CHR health factors in four categories: health behaviors, clinical care, social and economic factors, and physical environment.

The MPHD was compared with the percentage of health providers’ programs that address each of the health factors, as reported by interview participants. Health programs targeted predominantly health behaviors (52.5%), followed by clinical care (30%), social and economic factors (16%), and physical environment (1.5%) (Figure 3). The analysis of MPHD and PHLs’ efforts illustrates a disconnect between initiatives of PHLs and actual well-being needs.

PHLs described how their attention and services were focused on improving health and health services. Yet, PHLs also acknowledged that their efforts were insufficient and diluted. In such a wicked disadvantaged landscape, the PHLs find themselves facing major challenges as recognized by public leaders and public health scholars.40 To target these challenges, PHLs must develop continuous, long-term, and multi-tiered programs. These well-being initiatives geared toward social, economic, and environmental factors require resources not readily available in the Delta. Money, facilities, and personnel are simply unavailable. To keep the doors open, PHLs admitted chasing federal dollars for programs that did not necessarily get at the real issues residents faced. Having strained resources are all too familiar for PHLs. Even if resources became available will they be adequate or appropriate in addressing efforts towards alleviating health disparities related to social, economic, and environmental disadvantages?

For over a decade, scholars targeting public problems have been proposing that the “new shape of the public sector” demands the “rise of governing networks”, eco-structures and multi-sectoral collaborations.6,7,13,20,21,41,42

Public leadership scholars’ emphasize the use of cross-sector collaboration to address complex public problems and create “public value” like improved efficiency or fairness of public services.6,7,13,20,25,43 Theoretically, scholars pose that cross-sector collaborations can be used to dismantle wicked disadvantage by connecting various determinants of health and well-being, and the priority of bringing together multiple sectors is to target wicked disadvantage, initiating social change and enhancing overall well-being.1,6,7,13,19,20,24,25,40

PHL participants reflected the need to work together, across traditional boundaries, and beyond intra-agency settings toward a more collective impact. They acknowledged that well-being in the Delta relies upon the collaboration of nonprofit, health, education, community development, civic, and various public sector leaders to achieve program goals and reach those most in need. Additionally, PHLs acknowledged the need to collaborate directly with recipients of services and community members. PHLs described their use of cross-sector collaboration increases resources and availability of services and that they value and engage in cross-sector work.

Despite their valuing of collaborative work, both groups of participants, PHLs and RPs, admit that services, and even collective efforts, were insufficient in addressing well-being disadvantages. Both participant groups reported that social, economic, and environmental factors hinder well-being and prohibit the effectiveness of services and collaborations. For participants, collaboration was not enough. Enlisting in collaboration across sectors simply to increase resources and availability of services does not address wicked well-being disadvantage. Because significant and dynamic interrelationships exist among different levels of health determinants, initiatives that attend to and garner resources that support these determinants at all levels of well-being are more likely to be effective.

PHLs understand the need to work across sectors. However, until PHLs and their partners take full advantage of cross-sector collaboration to initiate social change and create public value, their collaborations may continue to be limited and reactive to social, economic, and environmental factors–which accounts for significant variance (70%) in overall health status.4 Thus, health disparities will continue to persist in the Delta and elsewhere. Moreover, the onus of addressing public health problems and wicked well-being disadvantage goes beyond the responsibility of PHLs, and their current engagement in cross-sector collaborations, and calls for health systems and policies to align with and support public health efforts to addresses social, economic, and environmental factors.19,22,23 With PHLs and other cross-sector partners–including those in regulation and policy–working to address social, economic, and environmental factors, wicked well-being disadvantages and their attendant health disparities can be appropriately addressed.

Recommendations for PHLs to enhance cross-sector collaboration

In designing, implementing, and maintaining cross-sector collaborations, PHLs must attend to social determinants of health, including social, economic, and environmental factors like conditions of the natural and built environment that support healthy and functioning communities.19,21,23 PHLs also may consider the following recommendations for leading collaborations across sectors. When engaging in collaboration, leaders begin by agreeing on the larger social challenges to be addressed and how these challenges affect health disparity and well-being. They acknowledge the responsibility and willingness to target these challenges. They focus on addressing one or two well-being challenges that would create the most significant impact. Leaders recognize and celebrate efforts that produce small victories for the group. These victories generate continued buy-in and “spiral up” momentum in creating community change.44

Cross-sector leaders understand that successful leadership in a network setting requires a different set of leader behaviors than found in a single-agency setting. Common behaviors of network leaders include treating all network members as equals, cultivating trust among those members, managing conflict effectively when it arises, and freely sharing information amongst network members.27 Leaders identify champions and sponsors who work diligently in promoting change or who use connections with others to push the effort forward.20 They assemble and develop strengths of partners while minimizing weaknesses, and recognize the assumptions that underlay cross-sector work–minimizing power inequalities and recognizing strategic value of difference.20,26 These leaders view individual differences in race, gender, educational level, and expertise as opportunities as opposed to problems; every voice is important in the success and sustainability of the collaboration.26 Cross-sector leaders practice the following strategies:

Limitations of Study

Although the results of the study demonstrated some interesting and insightful findings, there were two notable limitations. First, in terms of the sample, qualitative studies offer a snapshot in time and have a limited number of participants. In this case, although the population represented state-funded health and cooperative extension agencies, nonprofits, and grassroots groups, a relatively small sample size of public health leaders was used for this study. In part, the nature of the Delta landscape, as rural and under-resourced, affected the size of the pool. The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the study; however, a nuanced understanding of public health leadership in a wicked disadvantaged landscape in Arkansas can be acquired.

The small sample of PHLs also affected the sample size for resident participants as PHLs supplied a convenient list of potential willing participants. Moreover, although PHLs were successful in helping the research team identifies and set up interviews, PHLs reported that many RPs they reached out to be hesitant to participate in research. Employing other methods to acquire RP interviews (like identifying participants at other public events or accessing participants via door-to-door canvassing) would have benefited the team. To strengthen data analysis, given the limited sample, triangulation was acquired through the use of an integration of methods and data sources. Data sources were further strengthened through the enlistments of different spaces and persons.

Another limitation is related to the use of z-scores. Standard scores (such as z-scores) are the most basic standard score and are regularly used in public health research. Although z-scores account for how far a score is from the mean, a limitation of this statistical test is that z-scores assume a normal distribution. If a normal distribution does not exist, possibly a standard deviation of one to the left of the mean would not necessarily be the same distance to the right of the mean. If there was not a normal distribution of the well-being indicators in the Delta, using the z-score may have omitted significant well-being indicators or included some of less relevance.

This study focused on the practice of public health leadership and cross-sector collaboration to address well-being disadvantage. The findings indicate that the good intentions of collaborative PHLs may be insufficient in meeting this disadvantage. Collaborations fall short when only focused on increasing resources and networks. Efforts are limited when targeting clinical and health behaviors alone. The will and the need to address larger social challenges are not unnoticed by participants; these challenges just appear to be too insurmountable or irrelevant to their practice.

Public health disparities, interconnected and complex are effects of social, economic, and environmental disadvantage. PHLs may grapple with these disparities through collaborative efforts across sectors. Along with PHLs, community developers, educators, city leaders, policymakers, artists, and others are working in the public sector face a disadvantaged landscape. Working to resolve disparities within silos or even in collaborations will fall short without leaders’ acceptance of social responsibility to address well-being in a disadvantaged landscape.

Future research might include a larger sample size of public health professionals and organizations in the Delta, and may rely on more robust statistical analyses to identify areas of need and the nature of disadvantage. Also, further research on public health in the Delta could aim to understand the work other public sector leaders addressing social, economic, and environmental disadvantages (like poverty or homelessness) who may not explicitly identify their organizational mission as addressing “health” challenges and who may not have formal collaboration with public health providers. Talking directly with leaders in the public sector will allow for a better understanding of leadership towards overall well-being.

Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Commission.

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest.

This research project was partially or fully sponsored by Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Commission with grant number 4600033203.

©2020 Lane, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.