MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 6

1National Commission for Higher Education, Asmara, Eritrea

2Department of Accounting, College of Business and Economics, Halhale, Eritrea

3Department of Economics, College of Business and Economics, Halhale, Eritrea

Correspondence: Zemenfes Tsighe, National Commission for Higher Education, Asmara, Eritrea, Tel +2191162133

Received: April 04, 2017 | Published: May 11, 2017

Citation: Tsighe Z, Hailemariam S, Fesshaye H. Price elasticity of demand for tobacco consumption in Eritrea: an exploratory study. MOJ Public Health. 2017;5(6):208–213. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2017.05.00149

Smoking is a major cause of premature death and morbidity around the world. In Eritrea, the National Non-communicable Disease Risk Factors Baseline Survey of the Ministry of Health and WHO, conducted in 2005, noted that tobacco use is the main risk factor for non-communicable diseases such as respiratory infection, diabetes, cardio-vascular diseases and lung cancer in the country (8).This paper is an exploratory study into the sensitivity or responsiveness of increases in price of cigarettes on its consumption levels in Eritrea. The study used the Engle-Granger Ordinary Least Square (OLS) econometric modelling to estimate the (long-run) price elasticity of demand for tobacco. The model controls for per capita GDP, legislation for tobacco control (introduced as dummy variable) and past consumption. It is based on annual time series data from 1998 to 2012. The estimated long-run price elasticity of demand for cigarettes ranges from -0.8232 to -2.8122, with an average elasticity of -1.67. A comparison of the average price elasticity of demand for cigarettes in Eritrea with similar studies in other low- and middle income countries around the world reveals that the price elasticity of demand for Eritrea is more elastic. This could be attributed to the low income of people. As the demand is more price-elastic, increases in the prices of cigarettes could be more effective in reducing cigarette consumption. Seen from the point of the health benefits of overall reductions in cigarette consumption, the prices of cigarettes should be continuously monitored so that increases in prices of cigarettes (through increases in excise taxes) could be made to offset any future affordability of cigarettes due to increments in incomes in the population. The study could not assess the impact of increase in the prices of cigarettes on tax revenue due to data limitations.

Keywords: tobacco consumption, price elasticity, eritrea, diabetes, cardio-vascular diseases, OLS, GDP, price-elastic

ATSA, African tobacco situation analysis; IDRC, international development research center; GYTS, global youth tobacco survey; GSPS, global school personnel survey; EHIES, Eritrean household income and expenditure survey; BAT, British American tobacco; FCTC, framework convention on tobacco control; NSO, national statistics office; CPI, consumer price index

Globally people are trying to understand the economic dimension of tobacco use. One of the key economic issues considered in studies of tobacco use and control focus on how to reduce the demand for and supply of tobacco. These economic components of tobacco use and control hold an important place in designing effective and low cost policy tools to reduce the consumption of tobacco products. Generally, tobacco control policy tools are conveniently grouped into price and non-price policy tools. Up to recently the non-price tools like improving public awareness about the health hazards of tobacco use, smoking cessation programmes, banning of tobacco use in public places and tobacco advertising, etc. have been used as tobacco control measures, However, various studies have recently reported that the price-based policy tools are more effective and less costly than the non-price policy tools in reducing tobacco consumption.1‒3 Thus, tobacco control policies are increasingly making use of tobacco demand and cost modeling.4 Various studies have investigated the effects of prices of tobacco product on overall tobacco consumption.4‒7 Tobacco is addictive; however, the studies done to date indicate that tobacco behaves like other products in that its demand responds inversely to changes in price. Although most of the studies conducted to analyze the relationship between tobacco consumption and tobacco price are from high-income countries, the studies done in low and middle income countries also evince the negative effect of price or tax increase on tobacco consumption. Comparison of price elasticity of demand across countries further reveal that demand for tobacco products is more responsive to price changes in low and middle-income countries than in high-income countries. One of the major conclusions of (4, p13) is that “The global health and economic burden of tobacco use is enormous and is being increasingly born by low and middle income countries”. Eritrea is a low-income country. Tobacco use is one of the major health hazards in the country. The National Non-communicable Disease Risk Factors Baseline Survey of the Ministry of Health and WHO in 20058 reported that tobacco use is the main risk factor for non-communicable diseases such as respiratory infection, diabetes, cardio-vascular diseases and lung cancer in Eritrea. The same survey showed that 8% of the Eritrean population smoked on daily basis with steep increase in smoking prevalence with age up to 44years. When the study was repeated in 2012, 9.2% of the male population was smoking on daily basis, but it was 18.5% for males in the age group of 35-44years.

The survey conducted by the Tobacco Free School Environment Initiative under the African Tobacco Situation Analysis(ATSA),9 which was sponsored by the International Development Research center (IDRC), Canada, and conducted in 2009/2010, for Eritrea-wide students and school personnel showed that the age at which experimentation with tobacco products starts is falling and smoking prevalence is increasing, compared to the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) and Global School Personnel Survey (GSPS) study surveys10 conducted by the Ministry of Health and WHO in 2005. In overall, 12.2% of the surveyed students had tried tobacco prior to the survey. The survey of school personnel9 revealed that one out of four school personnel ever smoked cigarettes, and 16% of the school personnel were current smokers. The proportion of current smokers among the 13-15year olds increased from 2.2% in 2005 to 4.2% in 2009. A new phenomenon in Eritrea is the increasing number of female and underage tobacco users.9 The Living Standards Measurement Survey indicated that tobacco consumption expenditure for 2002 in Eritrea was Nakfa* (*Nakfa is the legal tender of Eritrea) 29,580,264.00. When compared to the 1996-97 Eritrean Household Income and Expenditure Survey (EHIES), tobacco consumption in Eritrea showed an upward trend. For instance per-capita tobacco expenditure in the capital, Asmara, increased from Nakfa 14.00 in 1996/97 to Nakfa 40.00 in 2002. Although tobacco use prevalence rate in the country is relatively low, the threat of tobacco use remains a serious public health issue. Since Eritrea is at the early stage of the tobacco epidemic, there is high potential for increase in tobacco use which makes the country a good candidate for market penetration by the tobacco industry, particularly the British American Tobacco (BAT), which has a monopoly on the Eritrean cigarette market. In view of this threat, Eritrea has been trying to control the consumption of tobacco products through legal instruments and anti-tobacco campaigns. In 2004, Eritrea promulgated Proclamation 143/2004 – Proclamation to Provide for Tobacco Control11 in Eritrea. The proclamation, which is based on the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), contains 11 articles and provides various provisions to discourage the consumption of tobacco products. The proclamation bans advertisement of any tobacco products, any types of labeling like “low tar”, “light, mild”, etc., mandatory health warning labels covering not less than 30% of the principal display areas of cigarette packets, sales of tobacco products in designated shops only, banning of smoking in public places, prohibition of sales of tobacco products to minors, and legal measures for offenses or breaches of the proclamation. However, there is lack of institutional commitment to the imperatives of the Proclamation. There is neither an institutional arrangement for its enforcement nor a litigation procedure for non-compliance, and the country has now very low regulatory resistance to tobacco promotional activities and illicit trade in tobacco products. Moreover, the Proclamation is not properly integrated into the national legislation. Various tobacco industry agents are using this gap to promote their tobacco products through T-shirts and other items that bear cigarette brand names; they also use street vendors, most of whom are poor women and children, as retail outlets to sell smuggled cigarettes that don’t comply with the Proclamation, thereby expanding their market to their products. This poses serious threat to public health. This paper is an exploratory study, which seeks to determine the degree of consumer responsiveness to cigarette price changes using annual time series data from 1998 to 2012 for Eritrea. It also presents a comparison of the responsiveness of Eritrean cigarette consumers to price changes with similar studies done in other low- and middle-income countries. The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the sources of the data used, how each data series is measured and the methodology employed in analyzing the data. Section 3 presents the results of the study using descriptive/graphical means and regression modelling, including a discussion of the findings. Section 4 provides some concluding remarks, including recommendations. In Section 5, limitations of the study are presented. Finally, acknowledgement and references are provided.

Data sources and measurement

Cigarette Consumption

Data on total cigarette consumption (in kg) on an annual basis from 1998 to 2012 was obtained from the British-American Tobacco (BAT) Company in Eritrea, which has been the only tobacco company operating in the country during the period under study. This period was selected for the completeness and reliability of the available data. The data series was converted to per capita consumption of cigarettes (people aged 15 years and above) using demographic data obtained from the National Statistics Office (NSO) of Eritrea. These consumption figures do not take account of smuggled cigarettes into Eritrea.

Cigarette Prices

Monthly retail prices of brands of packets of cigarettes in the market were obtained from the National Statistics Office (NSO) of Eritrea. These monthly retail prices of brands of packets of cigarettes were averaged to determine annual average retail price for each brand. From these annual prices by brands of cigarettes, annual average price of cigarettes was obtained by taking a weighted average of the prices of brands of cigarettes, where quantity sold of each brand was used as a weight. The resulting series of average retail price of packets of cigarettes was then adjusted for inflation using Consumer Price Index (CPI) obtained from NSO of Eritrea, and are expressed in real year-2000 prices in Nakfa.

Income of consumers

The level of per capita income, which is one of the determinants of level of consumption of cigarettes, is unavailable for most of the years under consideration. Given this lack of data, per capita GDP is used as a proxy variable for per capita income. Annual real GDP figures (in year-2000 USD prices) for Eritrea were obtained from the African Development Bank website.12 For the per-capita GDP calculation, population figures were obtained from NSO of Eritrea. Correlational analysis of data obtained from the African Development Bank website12 on GDP and household final consumption expenditure over the years 2000-2009 shows that there is a strong positive correlation between the two variables, indicating that per capita GDP is a good proxy for per capita income.

Tobacco control legislation:

In Eritrea, Proclamation 143/2004, A Proclamation to Provide for Tobacco Control, was promulgated in 2004 to protect the present and future generations from health hazards and other consequences of tobacco use. The core objectives of the Proclamation are to:

Methodology

The study used both descriptive and regression analysis to explore the relationship between price and tobacco consumption in Eritrea. Correlational graphs are used to describe the co-variability of each of the independent variables with the dependent variable over time. Econometric regression analysis is used to quantitatively determine the impact of changes in price of cigarettes on cigarette consumption, using annual time series data for the1998 – 2012 period. Generally, there are two traditional regression models used to estimate a function of demand for cigarettes: static and dynamic demand models.13 The dynamic demand model has two versions; namely, one that assumes that demand in a given period is affected by the demand in the previous period (myopic addiction demand model), and another that assumes that demand in a given period is affected by both demand in the past and in the future periods (rational addiction demand model). In this study, the static and the myopic addiction demand models are considered, and both models have been fitted to the data using various functional forms. However, only the most significant models are presented and discussed. The Engle-Granger approach13 was used to estimate the long run price elasticity of cigarette consumption. As the tobacco market in Eritrea is very small relative to the world tobacco market, and as the country imports almost all of its tobacco leaf and/or manufactured tobacco products, this study assumes price of cigarettes as exogenous variable.

Descriptive analysis

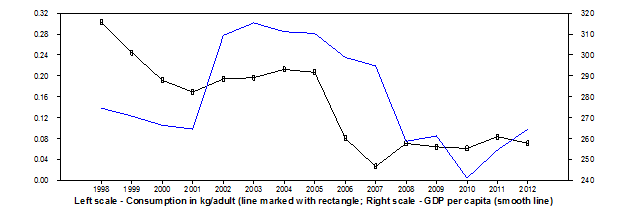

In this study it was found that there has been a general decline in the overall consumption of cigarettes, measured on per capita basis, over the period under consideration. Figure 1 depicts the trend of the per-capita consumption of cigarettes over the years 1998-2012. Overall, there has been a general decline in per capita cigarette consumption. In 1999, the excise tax on tobacco products was increased from 50% to 100%. Similarly, in 2004 A Proclamation to Provide for Tobacco Control (Proclamation 143/2004) was promulgated. The figure shows that in the years following the increase in excise tax and introduction of the tobacco control legislation, the consumption of cigarettes declined sharply.

The studies have looked into the relationship between consumption and price of cigarettes over the years, and have found out that there has been an overall negative relationship between the two variables. Figure 2 shows the correlational pattern of consumption and price of cigarettes over the years.

The studies have found positive relationship between per capita cigarette consumption and per-capita GDP over the years 1998 to 2012. Figure 3 shows the correlational pattern between the two variables.

Figure 3 Correlational graph of consumption of cigarettes and GDP per capita (USD 2000) (1998-2012).

Regression analysis

In time series analysis it is important to determine the stationarity of the data and the order of integration of each variable considered before proceeding to the analysis of the data. Nonstationary series for which stationarity can be achieved by differencing d times is said to be integrated of order d. The usual way of testing for the order of integration is to perform the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test14 for unit root. ADF test were performed for the variables real per capita annual cigarette consumption, real per-capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and real retail price of packets of cigarettes, and the first two were found to be nonstationary. However, both were found to be stationary in their first difference (Table 1).

Variable |

Testing whether stationary in: |

Trend |

Intercept |

No. of lags |

T-value |

Level of Integration |

Per capita cigarette consumption |

Levels |

Yes |

Yes |

1 |

-3.135 |

I(1) |

Per capita cigarette consumption |

First differences |

No |

No |

0 |

-2.756*** |

I(0) |

Real retail price of cigarettes |

Levels |

No |

No |

1 |

-3.703** |

I(0) |

Real per capita GDP |

Levels |

Yes |

Yes |

1 |

-1.659 |

I(1) |

Real per capita GDP |

First differences |

No |

No |

0 |

-3.333*** |

I(0) |

Table 1 ADF Test results for Eritrea cigarette demand data, (1998-2012)

***significant at the 1% level, **Significant at the 5% level.

To estimate the long-run demand relationship, this study uses the Engle-Granger Method.13 For each demand model considered, we estimated a long-run equation with the data in levels, and then tested the residuals of the resulting model for stationarity. The residuals for each model were found to be stationary. This is evidence that the long-run models are cointegrated. This process estimates Ordinary Least Square (OLS)1 regression model in order to discover the coefficients of the long-run stationary relationship between the non-stationary variables. Though the approach ignores short-run dynamic effects and the possibility of endogeneity, it is justified on the grounds that the OLS estimators are super-consistent (i.e., due to the presence of cointegration they converge to their true values at a faster rate than conventional OLS estimators with stationary variables)13 The dependent variable is annual average consumption of cigarettes, measured in kilogram, per adult aged 15 and above, and is regressed on average annual price, per capita GDP, and a dummy variable representing the tobacco control legislation. The results are given in Table 2 below.

Independent Variables |

Static Models |

Myopic Models |

||

Model 1 Linear |

Model 2 Semilog (lin-log) OLS |

Model 3 Linear |

Model 4 Semilog (lin-log) OLS |

|

Cointegration Relationship |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

constant |

0.2873* (1.99) |

0.0878 |

0.1403 (0.84) |

0.0756 |

Real price of cigarettes (Nkf 2000/packet) |

-0.0212** |

-0.4074** |

-0.0103 |

-0.2561* |

Real GDP/capita (USD 2000) |

0.0003 (0.65) |

0.2003 (0.60) |

0.0003 |

0.1604 |

Regulatory (Dummy) |

-0.1223*** |

-0.1219*** |

-0.0799* |

-0.0946** |

Past Consumption |

- |

- |

0.2991 (1.30) |

0.0513 |

Summary Statistics: |

||||

Adjusted R-sqr |

0.8374 |

0.8441 |

0.8569 |

0.8331 |

Standard error of regression |

0.038 |

0.037 |

0.034 |

0.036 |

Elasticity: |

||||

(Long-run) price elasticity |

-1.1875 |

-2.8122 |

-0.8232 |

-1.8634 |

(Long-run) income elasticity |

0.5792 |

1.3826 |

0.7713 |

1.1671 |

Table 2 Results of the regression analysis

***significant at 1 percent, **significant at 5 percent, *significant at 10 percent t-statistics are given in brackets, beneath their respective regression coefficients Price and income elasticity are calculated at sample means.

The signs of the regression coefficients of the independent variables are as expected. The regression coefficient of price is negative and significant in almost all of the models considered. Likewise, the regression coefficient of the tobacco control legislation which is entered into the model as a dummy variable is negative and highly significant in most of the models considered. The regression coefficient of per capita GDP and per capita past consumption is positive as expected but not statistically significant even at 10% significance level. The results for the price elasticity of demand indicate that price elasticity ranged from -0.8232 in the myopic lin-lin model to -2.8122 in the static lin-log model, with an average elasticity of -1.67. In three of the four models, the price elasticities are found to be elastic. In general, taking the average elasticity of -1.67 as a representative value of the elasticities, the interpretation is that a 10 per cent increase in the price of cigarettes is associated with a decline in the consumption of cigarettes of 16.7 per cent on average. Similarly, income elasticity ranged from 0.5792 in the static lin-lin model to 1.3826 in the static lin-log model, with an average elasticity of 0.97. Almost unitary elastic. In general, taking the average elasticity of 0.97 as a representative value of the elasticities, the interpretation is that a 10 per cent increase in real income is associated with an increase in the consumption of cigarettes by 9.7 per cent on average. Overall, the results show that cigarette consumption is more sensitive to changes in price than changes in income. A comparison of the long run price elasticities derived using the different models with similar works in other countries indicated that the price elasticity for the static lin-log model (-2.8122) stands out as an outlier. Overall, the average price elasticity of -1.67 suggests that the responsiveness to price changes is relatively higher in Eritrea compared with results obtained in other low- and middle income countries as shown in Table 3. This may be attributed to the low income of people in Eritrea.

Country |

Estimated (Long- Run) Price Elasticity |

Study |

Data |

Brazil |

-0.80 |

Da Costa e Silva (1998) |

Annual time series, 1983-1994 |

China |

-0.66 |

Hu and Mao (2002) |

Annual time series, 1980-1997 |

Morocco |

-1.54 |

Aloui (2003) |

Annual time series, 1965-2000 |

Papua New Guinea |

-1.42 |

Chapman and Richardson (1990) |

Annual time series, 1973-1986 |

South Africa |

-0.69 |

Economics of Tobacco Control in |

Annual time series, 1970-1994 |

Zimbabwe |

-0.85 |

Economics of Tobacco Control in |

Annual time series, 1970-1996 |

Table 3 Comparison of Estimated long-run price elasticity’s in low- and middle income countries

Source: IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention (2011) .15

Impact of raising the price of cigarettes (or tax) on tobacco consumption

To assess the impact of raising the prices of cigarettes (or tax) on tobacco consumption, the study employed each of the four cigarette consumption regression models presentedin Table 2. The result in figure 4 is based on 2012 values for GDP and also for the dummy regulatory variable, and assesses the impact of change of the average price of cigarettes in year 2012 on the level of consumption for the four price elasticity’s. Note that the annual increase in real price of cigarettes over the span of the period under study was about 2%. The figure shows that regardless of the sensitivity or responsiveness levels of cigarette consumers to price increments, an increase in the price of cigarettes will lead to a decrease in the per capita consumption levels of cigarettes.

Cigarettes, like all other tobacco products, are lethal and their use has become a major cause of premature death and morbidity. The health, social, and economic burdens caused by smoking cigarettes are indeed quite huge. Although various measures and anti-smoking campaigns are being taken by governments and concerned organizations to reduce the use of tobacco products, the tobacco epidemic remains a major threat to public health everywhere. High Income Countries (HICs) have put in place potent price and non-price control measures, and the Tobacco Industry is shifting its marketing strategies to the Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) where tobacco control measures are absent, inadequate or weakly implemented. Identifying tobacco control tools that are less costly and highly effective is imperative if the fast expanding tobacco epidemic in the LMICs is to be curbed. Tax/price-based control tools have proven to be quite effective, but there are few studies done in the LMICs.

This study attempted to explore the sensitivity or responsiveness of cigarette consumption to increases in price of cigarettes at macro level using country level cigarette consumption data over a period of 15years. To the best knowledge of the authors, estimates of price elasticity of demand for tobacco are not available for Eritrea. The study used OLS econometric modelling to estimate the price elasticity of demand of cigarette consumption. The model controlled for per capita GDP, tobacco control legislation (introduced as dummy variable) and past consumption. Knowing the price elasticity of demand allows to predict the likely decrease in consumption if the price of cigarettes were to increase by a certain percentage, We believe that the results of this study are consistent with similar studies, even though the price elasticity of demand of cigarettes for Eritrea is more elastic (-1.67 on the average) compared to similar works in other LMICs, which we attribute to the low income levels of the population. Given this degree of responsiveness of tobacco consumption to price increases, adopting price-based tobacco control strategy in Eritrea will greatly contribute towards achieving the core objectives of the tobacco control legislation. Seen from the point of the health benefits of overall reductions in cigarette consumption, the prices of cigarettes should be continuously monitored so that increases in prices of cigarettes (through increases in excise taxes) could be made to offset any future affordability of cigarettes due to increments in incomes in the population. Limitations in data availability did not allow this study to look into the fiscal implications of increases in prices (or taxes) of cigarettes. However the high price elasticity of demand seems to suggest that further increases in the prices of cigarettes would more likely depress the revenue that may be collected from tobacco tax. Public policy makers need to weigh the public health and other benefits derived from it against revenues foregone before any hasty decision is made. Price elasticity’s of demand change with time due to a number of factors. This study may form a basis for future studies. Moreover, the need for accurate data pools at household and individual levels are too important to ignore. The availability of such data will enable a more reliable evaluation of the impacts of price increases on tobacco consumption at meso (population subgroups) and micro (household/individual) levels.

The data for the amount of cigarettes consumed do not account for smuggled cigarettes or other tobacco products. It should also be noted that the demand models used do not take into account possible effects due to smuggling or use of other tobacco products. The study could not assess the impact of increase in the prices of cigarettes on tax revenue due to data limitations.

This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Canada. The authors express their gratitude and profound appreciation to the IDRC for the support. The authors would also like to thank for the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2017 Tsighe, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.