MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 3

1Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social

2Rio Claro Popular Clinical Laboratory

3University of Costa Rica

4College of Clinical Microbiologists and Chemists of Costa Rica

5St Lucia University

6Central American Institute of Public Administration

Correspondence: Ronald Varela Calvo, Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social, Universidad de Costa Rica, Rio Claro Popular Clinical Laboratory, University of Costa Rica, College of Clinical Microbiologists and Chemists of Costa Rica, Universidad Santa Lucia, Central American Institute of Public Administration, Pérez Zeledón, San José, Costa Rica, Tel +50660364886

Received: November 17, 2020 | Published: September 27, 2021

Citation: Calvo RV. Prevalence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in patients admitted to the Labcore computer system of the clinical laboratory of Dr. Tomás Casas Casajús Hospital from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2019. MOJ Public Health. 2021;10(3):63-69. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2021.10.00363

Leishmaniasis is à disease caused by a protozoan of the genus Leishmania, with biological cycles in which humans can be a reservoir. It can manifest as visceral or localized cutaneous, which is what occur in Costa Rica. The diagnosis has many techniques, but the most used for speed, price and availability is the direct smear with Giemsa stain in Costa Rica and the HTCC (CCSS), where the amastigote is sought. Objective: to determine rates and prevalence percentages of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Hospital Dr. Tomás Casas Casajús de Osa (CCSS) from 2015 to 2019, classified by year, age and sex.

Materials and methods: Data were collected by analyzing the Labcore computer system, downloading files in TXT text format and converting them to Excel. The analysis is performed by simple calculations of rates and percentages, and reporting in tables and graphs.

Results: Of the 250 records from 2015 to 2019, 39 are positive for 15.6% and 169 are negative for 67.6%. Of the positives, the prevalence per 100,000 inhabitants per year, 2017 recorded the lowest value with 9.8 and 2019 the highest with 42.0. According to age, those 29 and under are 59% and those 30 and over are 41%. There are no significant differences in terms of gender, with 44% female and 56% male.

Conclusions: A good diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be made. This starts from the physician's assessment to the report of the result. The laboratory technique must be good, from sample collection to microscopic analysis, and there must be traceability. This favors the patient for a good treatment and avoids new infections. Cutaneous leishmaniasis infection does not have age and sex patterns; It will depend on the environnent and human behavior, in work and recreational activities and in the place of residence.

Keywords: leishmaniasis, vector, cutaneous, diagnosis, epidemiological, Giemsa, incidence, hospital Dr. Tomáscasas, amastigotes

LCL, localized cutaneous leishmaniasis; HTCC, hospital Dr. Tomás casas casajús; CCSS, cajacostarricense Del seguro social; MHO, ministry of health; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid

The flagellated protozoa of Leishmania genus induce a group of diseases called leishmaniasis, which are granulomatous in nature, and can manifest from healing skin ulcers to a systemic multi organ disease with complications at visceral level. It is a condition whose clinic will depend on the species of the parasite, and the immune status of the host.1,2

Leishmaniasis is a disease that needs to develop in its life cycle:

Leishmaniasis is a parasitological disease that can have three biological cycles using two hosts:

In its life cycle, the female phlebotomine sandfly vector feeds on the blood of the infected reservoir with amastigotes of the parasite. These amastigotes reach the insect's intestine where they multiply for several generations until they become metacyclic promastigotes, which are anchored in the hypo pharynx and proboscis of the vector. The vector, already infected with these infectious forms, upon feeding on another vertebrate animal or human being, transmits the metacyclic promastigotes, which are phagocytosed by macrophages and other types of mononuclear phagocytic cells of the new host, where they are transformed into amastigotes. After approximately 36 hours, they multiply in the infected cells, causing the macrophage to rupture, invading other leucocytes and affecting other tissues, starting the cycle all over again.1,4

In general terms, leishmaniasis can present two clinical manifestations: visceral leishmaniasis, which is the most severe, and cutaneous leishmaniasis, which is less severe and more common. It is classified into localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (LCL), Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) and diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL), which will occur depending on the species of the parasite, the geographical area, the immune status of the infected patient and the species of the vector. It is a disease that, according to Izasa-James, et al,5 affects 98 countries worldwide.

All clinical forms of leishmaniasis are present in the Americas. Table 1 below shows the geographical distribution of the clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis in the Americas:

|

Geographical distribution |

Clinical manifestation |

|

Central America and |

Cutaneous and mucocutaneousleishmaniasis |

|

South America América del Sur |

Cutaneous and diffuse Leishmaniasis – MucocutaneousLeishmaniasis |

|

North America |

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis |

Table 1 Geographic distribution of leishmaniasis types in America

Source: An overview of American Leishmaniasis and its epidemiological behavior

LCL lesions appear on exposed areas of the skin, especially on the face and upper and lower limbs. In warm climates it is normal to find them on the thorax due to human behavior, especially in males, who are used to work and sleep shirtless. Generally, the first lesion is a single one, but there may be several if the patient has been bitten several times by the infected mosquito. Its incubation period can be days, weeks and even months, where the first symptom will be a pink papule, which grows, passing through a nodule or plaque-like lesion, ending with a painless ulceration with a hardened border that tends to fill with fibrous tissue and become contaminated with bacteria and fungi, but impetigo, vegetative and nodular forms can also occur.6,7

The species that are related to the LCL according to the geographical area are Leishmania major and L. tropica in Southern Europe, Asia and Africa; L. Mexicana and related species in Mexico, Central and South America; and L. brasileiensis and related species in Central and South America.8

Most patients without immune involvement with LSL heal spontaneously; however, it is important to treat these lesions because they could eventually leave scars. Those patients with more than 5 to 10 lesions, with diameters greater than 4 to 5 centimeters, with evolution greater than 6 months and located in areas such as the face or joints, should be diagnosed. It is important to take into account that in some cases the treatments are toxic and their use should be limited. Besides, there are other infectious, neoplastic or traumatic pathologies that are similar to cutaneous leishmaniasis. A correct diagnosis should include three aspects:

The main risk factors for LSL according to the World Health Organization are socioeconomic conditions, because poverty increases the risk when individuals are located in areas where Phlebotomus vectors can develop, poor nutrition that causes the infection to evolve into its full form, and population mobility because there is migration to areas where the cycles of evolution of the protozoan may exist, environmental changes because of unplanned urbanizations that make the entrance to wooded areas where the parasite develops and finally, the climate change that has caused temperature changes, natural disasters, humidity, which make both transmitting insects and reservoirs develop better and humans move to areas endemic of the disease.

The diagnosis of the clinical laboratory of the LSL is given by:

The direct smear is the most widely used and first choice technique for diagnosing LCL. Samples are taken from clinical lesions suspected of LCL by scraping or biopsy, with a scalpel or aspirated with a syringe, depending on whether the lesion is open or closed. Then a smear is made with the obtained sample that is stained with Giemsa, which is the best staining method because it generates a good contrast to identify accurately and clearly the intra- and extra-cellular structures of the amastigote. As a recommendation, this sample should be rich in lymph and without blood, and without germs or mucus. Then an analysis is made under the microscope and reported as follows: Positive that ¨Se observed amastigotes of Leishmania sp.¨, and 2. Negative that ¨No observed amastigotes of Leishmaniasp¨. It is important to point out according to Jaramillo-Antillonet al.7that the possibility to find the parasite performing a direct smear is inversely proportional to the duration of the lesions. In this case there is a relation of time with probabilities of direct diagnosis, where 100% will have an accurate diagnosis before 6 months of evolution, 75% at six months and 20% at more than 12 months. For these last cases, of 1 year or more, it is important to perform parasite isolation tests by culture, molecular detection of the parasite DNA and serological tests. In Costa Rica, the diagnosis is made in all laboratories of the health system, public or private, and in all regions of the same by means of Giemsa staining, and for cases of doubt in the face of typical but negative, atypical lesions with a long evolution time, there is a national reference laboratory which performs cultures and molecular tests called Centro Nacional de Referencia de Parasitología del Inciensa.7,9,11–14

LCL is a public health problem in Costa Rica, it is colloquially known as ¨papalomoyo¨, and there are many endemic areas where the disease should be suspected. According to the Ministry of Health (MOH) 100% of the cases of leishmaniasis in the national territory are LCL, although eventually other manifestations such as visceral or mucocutaneous could occur, since the parasite species for these clinical pictures circulate sporadically in the national territory. It is an endemic disease in forest areas, due to ecological alterations of humans by deforesting and invading these places for agriculture and housing construction. The mosquito of the genus Lutzomyia, called ¨Aliblanco¨ in popular language, is the vector in this country and the reservoirs are the sloth bear and other mammals; within the common species of Leishmania spp. are the subgenus Viannia with the species Leishmania (V.) panamensis which is the most frequent and L. (V.) braziliensis as the etiological agents of LCL.15,16

Costa Rica is a Central American country of 51100 square kilometers, with a population of 5111221 inhabitants according to the 2020 institutional projection of the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC),17 with 2575541 males and 2535680. It is organized territorially in 7 provinces, each of these in cantons, and these in districts. The country is in a tropical zone where humid, rainy and some dry forests abound. The climate is suitable for multiple diseases involving insect vectors such as malaria, dengue, leishmaniasis and other infectious diseases. According to MOH's 2018 Institutional Report16 from 2013 to 2017, an average of 1,686 cases of leishmaniasis was presented with an average rate of 34.9 per 100,000 inhabitants. During 2017 it was when the highest number of cases occurred with 2,224 cases with a rate of 44.95 per 100,000 inhabitants. Moreover, in this same study it was observed that there were no marked differences between men and women, since 48% of the cases corresponded to female sex and 52% to male sex; moreover, the most affected age group was from 1 to 4 years followed by 5 to 9 years.

The HTCC has a population, according to projections for 2020 by INEC,18 of 31,139 inhabitants with 16,172 males and 14,967 females. It is located in a coastal region, with tourism and agricultural development, with a lot of forest area. It has a population of native residents of the area and foreigners, who have habits very likely to acquire infections through insect vectors, since they build their homes and hotels near jungle environments, and practice extensive agriculture invading wooded and swampy areas. At the HTCC the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis is made by direct smear using Giemsa stain. Laboratory technicians take the samples, supervised by microbiologists, who in turn stain and analyze the stained slides.

The objective of this study is to determine the incidence rates and percentages of LCL diagnosed in the HTCC of the OSA canton, Puntarenas Province, Costa Rica, from 2015 to 2019, classified by year, age and sex.

A Transverse Study of the total number of records of patients who were admitted to the Labcore Computer System of the clinical laboratory of the Hospital Dr. Tomás Casas Casajús de Osa, Puntarenas, Costa Rica, with the Leishmania Smear test, was performed and reported, from 2015 to 2019, to men and women of all ages.19

The variables measured were the presence or not of parasite amastigote in the samples reported as: Positive (when amastigote of Leishmania sp. was observed in the sample examined) and Negative (when amastigote of Leishmania sp. was not observed in the sample examined), classified by sex and five-year age.

Resources

The source of information is the Labcore Computer System of the Hospital Dr. Tomás Casas Casajús, which is an information system of the company Capris Medical, which provides the service to all the laboratories of the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS), which is in charge of public security in the country. The demographic data is obtained from the National Institute of Statistics and Census of Costa Rica.

Data processing

250 records were obtained from January 1st, 2015 to December 31st, 2019 with the Leishmania Smear test of the Labcore Computer System, by means of tools that the software has to filter the information by sex, age, results and test report date. This was generated in TXT text format that was later transformed to Excel format. These files are used for data selection analysis by means of dynamic tables and filters to choose the necessary information for the results report.

The following calculations were made for the records filtered by sex, age, date of report and result20

The points for a., b., c. and d., were calculated with ratios, where the number of records Positive for Leishmania sp., Negative for Leishmania sp., Lesion not compatible for cutaneous leishmaniasis and No report, were placed in the numerator, and the total number of records, from the entire study generated by Labcore from January 1, 2015 through December 31, 2019, in the denominator. For e. and f., by five-year age and sex, respectively, the number of Positive for Leishmania sp., by sex or by age, was placed in the numerator, and all positive records for Leishmania sp. In the entire period January 1, 2015 through December 31, 2019, in the denominator.21,22

The results obtained from the above mentioned calculations were organized in tables (Positive for Leishmania sp., Negative for Leishmania sp., Non compatible lesion for cutaneous Leishmania and No report), in line graphs (the annual incidence rates), in horizontal bars (percentage of positives by age) and in pie (percentage of positives by sex).

250 Labcore records were obtained from the period 2015 to 2019 at the HTCC clinical laboratory. From these 211 presented some annotations in the results space and 39 are only with the demographic data of the patients. In the following table are presented the quantities, absolute and relative, of the Positive and Negative for Leishmania sp., those that do not present results and those that were rejected for not having a lesion compatible with the LCL.

From the 39 Positives for Leishmania sp., it was calculated the incidence for each year, of the new cases that were diagnosed in the HTCC. The following figure shows the incidence behavior in time of this disease:

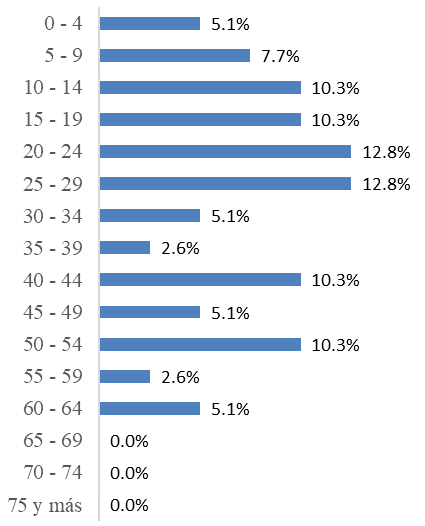

From the positive cases for Leishmania sp. it was observed that from 20 to 29 years old the highest percentage of LCL cases was registered, and after 64 years old leishmaniasis was not diagnosed. In the following graph the records with positive results for LCL were distributed in five-year periods from minor to major age in ascending form:

In addition, with respect to five-year age it was observed that from 20 to 29 years of age recorded the highest percentage of cases, and after 64 years of age no patients were diagnosed with LCL as shown in Figure 2:

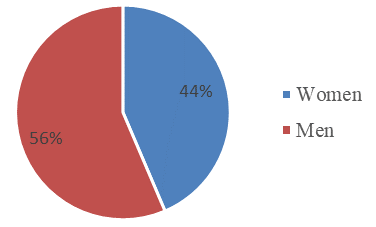

This study exposed that from the 250 Labcore records from 2015 to 2019 of the HTCC for Leishmania Smear (Table 2), 15.6% are positive, 67.6% are negative, 1.2% were not processed because the lesion was not compatible, and 15.6% had no results. As for the incidence per year (Figure 1), it was observed that the LCL had a pattern in time with a decrease from 2015 with 33 cases per 100000 population until reaching the minimum point in 2017 with 9.8 cases per 100000 population, and then a growth until 2019 with 42 cases per 100000 population. In addition, by age (Figure 2) from 0 to 64 years there were positive results for LCL, and over 64 years not, and those under 30 years were 59% and over 30 years 41%, those of 20 and 29 years were those with the highest percentage of positives with 25.6%, and those from 35 to 39 and 55 to 59 years 2.6% each being the last ones with the lowest amount. Finally, there is a slight, although not significant, predominance of positive cases of LCL in men with 56% over women with 44%.

|

Results |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

|

Positive for Leishmaniasp |

39 |

15.6 |

|

Negative for Leishmaniasp |

169 |

67.6 |

|

Injury not compatible with LCL |

3 |

1.2 |

|

No report |

39 |

15.6 |

|

Total |

250 |

- |

Table 2 Results of records entered into the HTCC Labcore (CCSS) January 1, 2015 through December 31, 2019

Source: Labcore of the HTCC

Figure 1 Leishmania prevalence rate in the HTCC (CCSS) from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2019 per 100000 population.

Source: HTCC (CCSS) Labcore.

Figure 2 Percentage of LSL positives according to five-year age of the Labcore records of the HTCC laboratory from 2015 to 2019.

Source: HTCC Labcore.

The records that did not present any results are lost information for the epidemiological system of the HTCC (CCSS) and the Canton of Osa. There is no way of knowing the causes of this situation because there are no logs that record the events of sample reception, nor protocols for this. However, starting from the base, and knowing the laboratory service as such, some reasons could be the omission of laboratory personnel to note the cause of rejection, poor recording of demographic data or noting the Leishmania smear test to patients who were not requested by the physician, and in the worst case, not transcribing the results to the Labcore of the patients who were tested. These situations are quality problems, and occur in many clinical laboratories worldwide. The analytical process for the Leishmania smear test consists of the pre-analytical phase which is the demographic data recording stage, the analytical phase is where the samples are taken from the patient, stained and observed under the microscope; and the post-analytical phase is when the result is reported. According to Cano and Fuentes23, errors are classified according to the phase and the impact they can have on the patient. In this case, errors can occur due to mis spelling the patient's name or the test requested, poor specimen collection, poor staining and misdiagnosis by the observer of the stained plate, and finally, poor transcription of the result.

It was observed that there is a time pattern of prevalence in the form of a valley (Figure 1), which can occur for two reasons, in the first case due to better or worse management of the vector or disease treatments and protective measures by the population, and in the second case, due to inefficient diagnosis by laboratory personnel.

There are data generated by this study (Figure 2) as that those over 64 did not present positive for LCL, those under 30 had more cases with 59% and the rest was 41%, the age ranges from 20 to 29 years presented the highest amounts with 25.6% and that there is no direct relationship between age and LCL infectivity, because although it is evident that in those under 30 represented the largest group of those affected by the disease, there were age ranges, such as 0 to 4, 30 to 34 and 60 to 64, which presented each 5.1%. With this information it should be deduced that age is not a risk factor for suffering from LCL, the variability of those affected by age ranges is evident, because there are even groups that did not present individuals with the skin problem. Having a large number of people affected by the LCL of 29 and less, gives rise to the following explanation, that minors who are in primary and secondary school, still have their schools near forest areas, in addition to their recreational activities will frequent wild areas such as rivers, beaches and mountains. One possible explanation for this is provided by Ampuero J, et al.24 who mentions that minors can have greater transmission because the parasite has evolved, found new secondary hosts, and even the human being himself has become one of these; and since infants and young people live with infected adults, and insect vectors exist peridomiciliary, transmission can easily occur. In the same study, it is mentioned that as a possible proof of this hypothesis, entire families with the disease have been found. The results of this work do not agree with those of the institutional memory of the MOH,16 of the incidence of LCL in Costa Rica from 2013 to 2017, where it is mentioned that the ages of highest incidence are those between 1 to 4 and 5 to 9, and obviously according to Figure 2 those affected in this study are those from 20 to 24 and 25 to 29. Nor do with the national study of Jaramillo-Antillon et al.7 where from 2011 to 2016 and in Table 1 of that study are children under 14 years are those who suffered more with the LCL, and those 60 years and older, had many cases. Compared with international studies according to Perez et.al.25 in Spain, 10% is in children under 12 years, in the case of the HTCC this age is not typified, however it was shown that children under 14 years, which includes those of 12, total 23.1%, in another study conducted in Colombia Velez et al.26 This comparative information deduces that age will not be a risk factor, in fact according to the World Health Organization11 it is not included as a risk factor.

The percentages by sex (Figure 3) show that there are no significant differences between men and women. Although the percentage is slightly higher in men, with 56%, than in women, with 44%, when the ratio 56/44 is calculated it gives a result of 1.3, that is, 1.3 men for every woman, but it is practically 1 to 1. As with age, and according to the WHO11, this is not a risk factor for contracting LCL; however, there are daily work and recreational conditions, such as farming and ecotourism, typical of this area, which can expose individuals to the phlebotomine sandfly vector, whether they are women or men. In addition, being in a jungle area and with houses and hotels being built nearby, both sexes are equally exposed. The study is similar to the results of the MSP16 report, where 48% are women and 52% men. In other latitudes such as Venezuela, according to De Lima, H et al,27 the frequency is higher in men, with ratios up to 1.8 times higher than those of women. Similarly, Sánchez-Saldaña et al.28 state that there is no predisposition by race or sex, Although they mention that there may be a slightly higher number of men, but they attribute this to the fact that in endemic areas they have to go out more to the countryside to do house work. In the case of Vélez et al.26 in Colombia, men predominate. According to another study in Ecuador by López et al.29 the place and time of residence showed a significant association with the frequency of LCL. Sex is definitely not a determinant of LCL, as variations in the results were observed in several studies.

Figure 3 Percentage of positives for LSL according to sex of the HTCC from 2015 to 2019.

Source: HTCC Labcore.

It is evident that more data are needed to generated a more precise study of the epidemiological information generated in this work. Before seeking more information such as specific clinical pictures of the patients, as their health status and socio economic conditions, it is important to get the idea that a good diagnosis of LCL should be made, since it can be confused with many skin lesions, and this makes its diagnosis represent a special care, both for the physician and for the clinical laboratory. According to a study conducted by Belizario et al.30 they found that 73.5% of the ulcers that arrived at the medical center where they conducted the investigation corresponded to causes other than LCL, and were found mainly in women. This information is very important because it generates the concern to better evaluate the cases, not only by the physician, but also by the laboratory personnel themselves. According to Montijo, et al.31 LCL ulcers should be differentiated from traumatic ulcers, stasis, tropical ulcers, ulcers due to sickle cell anemia, pyoderma, paracoccidioidomycosis, cutaneous neoplasms, syphilis and cutaneous tuberculosis, and other non-ulcerative lesions. And one of the ways to make this correct diagnosis, when there are no lesions with negative results, but with doubt, or lesions with a long period of evolution longer than 12 months, is by molecular tests, immunological tests or additional cultures, depending on the availability of the tests.7,12,30,31

The study had the limitations of having to depend only on the information from Labcore, that it was only data, of a Positive or Negative result, since other types of information do not appear such as the clinical history of the patients, where it is said where the lesions came from, time of evolution of the lesions or whether or not other treatments were used. The bibliographic information on this subject at the national level is a little deficient in quantity and quality, more and better work is found abroad.

In future research, it is necessary to try to carry out the study with fewer patients in order to review the clinical histories and learn about aspects that may be important for a more complete study. The study was limited only to the epidemiological and diagnostic part; however, this may be useful for future health professionals to execute one regarding the treatment of the population and the exact location of each patient in the Canton of Osa, specifically those who come to the HTCC (CCSS). And finally, the doubt that these results are correct is great, due to the factors mentioned above regarding the whole process of analysis, so there is a theory in this work that the values presented may be higher, so it would be necessary to conduct a field study to search for patients with these lesions and vector insects to generate a work that includes information by geographic area and socio economic status, in addition to the LCL diagnoses.

This work has the value of giving epidemiological information to the Hospital Dr. Tomás Casas Casajús de Osa because it had never been done with respect to this disease in terms of behavior over time, age and sex. Although in this place the disease has less incidence than in other parts of the country, itis a zone where the cases can occur more since it has many predisposing factors such as jungle areas, Phlebotomus vectors, reservoirs and behavior of its in habitants predisposing to the infection. With this information, the clinical laboratory can initiate a standardization of the diagnostic process, applying greater controls in the traceability, and better technical diagnostic methodologies, such as the sampling through training, better management of the reagents and staining, of course, refreshing in the analysis of the slides for the search of Leishmania sp.

It is important to mention, that in some cases, due to lack of Giemsa reagent, many of the tests could have been performed with Wright staining that is a reagent that does not have the same sensitivity and therefore it was reported negative, besides errors in the information, as mentioned before, due to omission and bad transcription of demographic data and results, by the laboratory staff. The way of reporting had to best and ardized in the research, because in the software appeared different kind of annotations, for example Positive, Positive for Leishmania sp, Amastigous for Leishmania sp, and Leishmania spis observed. The national information was very brief, and in many cases it did not say exact figures, so the points of comparison were not the best.

With all the information collected, both the one generated by the Labcore records and the bibliographic information, it is important that the HTCC clinical laboratory intends to apply in the diagnosis of LCL greater controls in the traceability, and to improve the diagnostic methodology, starting from the sample collection and staining of the sample, and improving the capacity of the persons in charge of the analysis of the slides for the search of Leishmania sp. amastigotes, this by means of trainings. Besides, it is important to establish controls for the handling of the staining reagents, verifying the expiration dates and the sufficiency.

All this will bring epidemiological benefits that will benefit the users because this is a region in which it does not matter whether the person is older or younger, male or female, everyone has the same possibility of being infected by Leishmania sp. The faster and more correctly the diagnosis is made, the sooner the patient is cured and the disease is prevented from becoming complicated with disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis or inadequate scarring, and the contagion is prevented from continuing to occur among more inhabitants. In addition, it will give the starting point, instead of being negative, to look for other causes of lesions of infectious, traumatic or neoplastic origin, and avoid giving treatments for LCL that may be toxic.

The researcher would like to thank HTCC’s clinical laboratory for its help in accessing information.

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

©2021 Calvo. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.