MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 2

1Department of Women

2Associated professor, Uppsala Religion and Society Research Centre, Uppsala University, Sweden

Correspondence: Marlene Makenzius, Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala University, Sweden, Tel +46761131076, Fax +4663199602

Received: June 16, 2017 | Published: June 26, 2017

Citation: Makenzius M, Stålhandske ML. Induced abortion-a clinical procedure lined with existential attitudes and needs among women and men, in Sweden. MOJ Public Health. 2017;6(2):296–301. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2017.06.00164

Aim: To investigate the prevalence of existential attitudes and needs among women and men who have requested an induced abortion.

Methods: A questionnaire consisting of 51 multiple-choice questions was used to collect information from 499 women who had requested an induced abortion and 371 male partners.

Results: Overall, the results revealed a great variation in spiritual and attitudes in relation to an induced abortion procedure, among both women and men. Spiritual beliefs were more common among women (45%) than among men (32%). Half of the women (50%) and a third of the men (33%) considered what had existed in the womb as being a child. A higher proportion of women (46%), than men (21%), thought about guilt and morals. After the abortion, about half of the women (54%) and 42% of men felt everything related to the pregnancy was over, and some thought about the child they could have had (50% women and 32% men). Induced abortion is a clinical procedure lined with existential aspects, characterized by four phases; “Fertility awareness – happiness and sadness”, “Decision–negotiating about life and future”, “Abortion – social support and responsive staff”, and “Post- abortion – continuing life and lingering thoughts”.

Conclusion: Men commonly displayed existential thoughts, feelings, and needs related to abortion, although not to the same extent as women. There is scope for addressing existential aspects during the abortion procedure and also with respect to men’s needs.

Keywords: induced abortion, existentiality, spirituality, Fetus, morality, fertility awareness, medical ethics, Likert-scales, attitude, socioeconomic, Nordic context, paradoxical emotion, psychology, secular societies, Uppsala, Sweden

In 2008, about one in five pregnancies worldwide ended in abortion.1 In Sweden, the current Abortion Act from 1975 permits abortion, on the woman’s request, until the 18th week of gestation.2 After the 18th week, the National Board of Health and Welfare can approve an abortion under certain circumstances, but after gestational week 22, abortion is not allowed. Most abortions (89%) are performed early in pregnancy, before nine weeks.2 In the USA, women seek abortion for reasons related to their circumstances, such as socioeconomic aspects, age, health, parity, and marital status:3 these reasons are similar for women and men in a Nordic context,4,5 especially for women and men involved in repeat abortion.6,7 Men’s role in sexual and reproductive health is not always clear. In some studies, men tend to refrain from responsibility in sexual and reproductive health issues,8,9 whereas, in other studies, men want to be involved.4,10‒12 Even if male partners are happy with the woman’s decision to have an induced abortion and have positive emotions post-abortion, abortion can sometimes be related to strong and paradoxical emotions in both women and men.4,13,14 However, there is a strong case for the lack of c complications in women in relation to abortion.15 From the perspective of the psychology of religion, existential issues include complicated queries related to the foundation of human existence, such as meaning, death, identity, and responsibility.16 The existential dimension is a central concept within the psychology of religion, and contemporary research within this field focuses on how existential questions are related to religion, spirituality and mental health. The concept is particularly important for research on secular societies, where the influence of a religious institution has diminished.17‒19 Existential questions are related to both fundamental and human dimensions of existence, and the most common questions relate to death, meaning, identity, isolation, freedom, connectedness, and responsibility.17‒21 In ordinary life, questions concerning these issues are not often pondered, but at critical moments in life, they often surface. When a person is presented with a serious illness, an ultimate decision, or new situation that tests a person’s identity or view of life, the individual is often challenged to deal with existential questions.20‒22 This demanding task can also be related to experiences of maturation.23 This study aims to investigate the prevalence of existential attitudes and needs among women and men who have requested an induced abortion. Existential attitudes and needs were limited to expressions and actions related to life and death, identity, morality and view of life; in other words, questions that went beyond those which the abortion situation socially or practically demands.

Subjects

This cross-sectional survey was among Swedish women and men involved in an induced abortion in one of 10 clinics in Sweden during the period January to August 2009. The clinics included were situated in both rural and urban areas and covered a third of the country. Questionnaire packages (n=1041) were consecutively handed out to all eligible women seeking an induced abortion. The women also received a similar questionnaire, in which she was invited to give to the man involved. The number of questionnaires handed out was based on the number of abortions performed at each clinic during the previous year.

At the first appointment, oral and written information about the study was provided, such as participation was voluntary and anonymous. The two questionnaire-packages were also handed out, together with two pre-paid envelopes. Women who were unable to read and write Swedish were excluded. Almost half of the women (n=499) and 371 men returned the questionnaire (48%). The study was approved by the Regional Medical Ethics Committee in Uppsala, Sweden (2008 –289).

Questionnaire and measures

A questionnaire with 51 multiple-choice questions and five open-ended questions was used. A pilot study was conducted in two clinics to validate the questions and to test the procedure. The majority of the questions were study-specific, and were constructed and revised specifically for this survey in collaboration with experts, health care providers within the field, and the women and men involved in an induced abortion. Three types of questions were included in this study:

The questions were developed partly on the basis of researchers within the field and health care professional’s experiences, and partly according to a qualitative pilot study specifically designed to explore existential attitudes in relation to abortion.

For the analysis, the data were transferred into the Statistical Package of the Social Science (SPSS, 18.0). Several items from the questionnaire were dichotomised through transforming the scales into ‘yes’/’no’ (i.e. earlier children and earlier abortions); transforming ordinal data into ‘high’/‘low’ (educational level); computing nominal data (i.e. spiritual=belief in God/spirit/force of life, non-spiritual=no belief/do not know (Table 1) (Figure 1); and, transforming the 5-point Likert-scales into ‘no/low prevalence1‒3/‘prevalence’4,5 (i.e. items about existential attitudes; Table 2). The chi-square test was used to investigate differences between women and men, and the level for statistically acceptable differences was set at p=< 0.05: Pearson Chi-Square and Fisher’s Exact Test were used for sub analyses. For the open questions, latent content analysis,24 in which meaning units are identified and then categorized, was used to retrieve a description of the respondent’s thoughts and feelings. In order to strengthen the credibility, the categories were discussed and rearranged until all the recording meaning units had been assigned to final categories and the overarching theme developed.

Background characteristics

A majority of the participants were born in Sweden (Table 1) and had high school education (women=57%and men=66%): 25% of women and 19% of men had university education. A majority (women=77%; men= 87%) had an ongoing relationship, and most participants had someone to share their innermost thoughts and feelings with (women= 88%; men= 81%). About 40% of the participants had children.

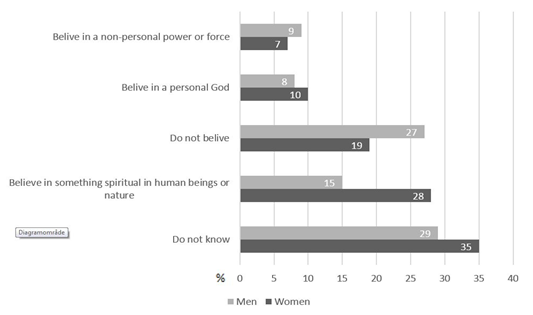

Having a spiritual belief (belief in a personal God, a non-personal power/force, or something spiritual in human beings/nature) was reported by 45% of the 499 women (n=224) and 32% (n=119) of the 371 men (Figure 1). Nineteen percent (n=93) of women and 27% (n=101) of men were not spiritual, and 35% (n=175) of women and 29% (n=106) of men did not know what to believe.

Women who reported spiritual beliefs were not more satisfied or dissatisfied with the treatment by health care staff than women without spiritual beliefs (p=0.742). Men with spiritual beliefs were more commonly dissatisfied (38%) with the personal treatment by health care staff than those without spiritual beliefs (20%: p=0.009).

Existential attitudes in relation to an induced abortion

More than half the women (71%) and men (56%) thought about what had existed in the womb as a pregnancy (Table 2). About half the women (57%) and 40% of men thought it was a beginning life and an embryo (52%) or foetus (37%). Half of women (50%) and a third of men (33%) thought about what which had existed in the womb as a child.

Table 2 shows that in relation to the abortion, a majority of women (74%) and half of men (52%) thought about their future, and their close relationships (women=66%; men=45%). Two-thirds of women (66%) and 28% of the men thought about their body and fertility. In addition, a higher proportion of women (46%) thought about guilt and morals than men (21%). In relation to the abortion, some women (25%) and some men (10%) did, or wanted to do, something special to grieve (22%) and/or to end the process (11%). After the abortion, about half of women (54%) and 42% of men felt everything related to the pregnancy was over, although some thought about the child they could have had (women=50% and men=32%). For women, the sub-analyses highlighted associations between spiritual beliefs, the need to do something special to grieve (p=0.037), and a view of the child as an angel (p=0.025), Table 2. For men, the sub-analyses revealed associations between spiritual beliefs and the need to ‘let off steam’ (p=0.012).

Figure 1 Belief or non-belief in a personal God, a non-personal power or force, or something spiritual in human beings or nature, among abortion-seeking women* (n=499) and their partners** (n=371).

Missing values: women* 2%, men** 12%.

Abortion – a clinical procedure lined with existential aspects

The open-ended question “Something else you would like to tell or comment”, was completed by 99 of the 499 women and 57 of the 371 men. A wide range of emotions was revealed in the qualitative analysis; however, existential attitudes dominated these responses. A comprehensive description of the overarching theme “Abortion – a clinical procedure lined in existential aspects”, and the four related categories “Fertility awareness – happiness and sadness”; “Decision – negotiating about life and future”; “Abortion – social support and responsive staff”; and, “Post-abortion – continuing life and lingering thoughts” is illustrated in Figure 2. The variety within the material was seen within specific answers, for example, some respondents simultaneously described the decision in terms of a planning and negotiating process, or their post-abortion attitudes in terms of continuing life and continuing bond.

An abortion is an event involving bodily procedures and experiences. The respondents related the abortion to themselves in terms of their health and fertility, and in relation to their sense of support. Thoughts on future pregnancies were imminent. Some men and women described the pregnancy as an assurance of their fertility, “I felt it was nice to know that we could have children, but we had no intention to have a child at this moment in life” (man). Some were worried about not being able to become pregnant again, “A fear that I might not be able to get pregnant again” (woman) and "Will I be able to conceive a pregnancy again? I cried over that question” (man).

For some men and women, the pregnancy was instantly followed by the decision to abort. They experienced no ambivalence, neither before nor after the abortion and decided on an abortion in relation to marital status, social relationships, education plans or economics. Many expressed gratefulness for the accessibility of Swedish abortion care. For others, the pregnancy was followed by a period of going through the alternatives, trying to find out what the right decision would be. For these respondents, the decision became a part of a process for reviewing their identity or view on human life or moral inclination: “Thought about my life as a whole, what has happened and what will happen. The meaning of life and what I want with my life ...” (woman). Others expressed how they tried to repress similar thoughts because they thought this would make the decision more difficult.

Some women and men stated they agreed about the decision with their partner, however, some displayed a feeling of being overruled by their partner. The decision was part of a process or a lack of negotiation, and some respondents described the decision as having already been made by their partner: “Everything was already settled, I had no choice” (man), “I felt hopelessness and despair without power to influence” (man), and "Deep down in me, I wanted to keep the baby but could not do it when my partner wanted to terminate the pregnancy" (woman). Respondents that found the decision more difficult also defined the pregnancy in terms of a child or thoughts about becoming a parent.

Characteristics |

Women (n=499) |

Men (n=371) |

Age |

||

Range/m/ med |

14 – 47/26/24 |

16 – 63; 29/27 |

Country of Birth |

||

Sweden |

465 (93) |

334 (90) |

Other Nordic country |

4 (1) |

5 (1) |

Europe |

7 (1) |

11 (3) |

Outside Europe |

19 (4) |

21 (6) |

Education |

||

University |

123 (25) |

72 (19) |

High school |

285 (57) |

243 (66) |

Compulsory |

86 (17) |

55 (15) |

Occupation |

||

Employment |

215 (43) |

227 (61) |

Sick leave or unemployment |

65 (13) |

56 (15) |

Student |

164 (33) |

75 (20) |

Parental leave |

43 (9) |

10 (3) |

Stable Relationship |

||

Yes |

384 (77) |

324 (87) |

Have Someone to Share Innermost Thoughts and Feelings With |

||

Yes |

441 (88) |

300 (81) |

Child(Ren) |

||

Yes |

200 (40) |

158 (42) |

Table 1 Characteristics of abortion seeking women (n= 499) and their partners (n=371)

Variables |

W (n=499) |

M (n=371) |

P-Value |

I Thought about what Had Existed in my Womb/Partners Womb as… |

|||

a) …a pregnancy |

337 (67) |

166 (48) |

<0.001 |

b) … a beginning life |

286 (57) |

149 (40) |

0.001 |

c) …an embryo or foetus |

262 (52) |

138 (37) |

0.007 |

d) …a child |

249 (50) |

123 (33) |

0.001 |

e) …a clot of cells |

119 (24) |

66 (18) |

0.275 |

f) …a soul that can return |

74 (15) |

30 (8) |

0.032 |

In Relation to the Abortion, I Thought a Lot about … |

|||

a) …my future |

369 (74) |

194 (52) |

<0.001 |

b) …my close relationships |

330 (66) |

168 (45) |

<0.001 |

c) …my body and fertility |

330 (66) |

102 (28) |

<0.001 |

d) …guilt and morals |

230 (46) |

79 (21) |

<0.001 |

e) …the meaning of life |

191 (38) |

72 (19) |

<0.001 |

f) …life and death |

186 (37) |

72 (19) |

<0.001 |

In Relation to the Abortion, I Did/Wanted to do Something Special to… |

|||

a) …grieve |

126 (25) |

37 (10) |

<0.001 |

b) …end the process |

108 (22) |

40 (11) |

0.001 |

c) …be reconciled with it all |

98 (20) |

29 (8) |

<0.001 |

d) …ask for forgiveness |

97 (19) |

32 (9) |

<0.001 |

e) …let off steam |

97 (19) |

30 (8) |

<0.001 |

f) …mark what had happened |

64 (13) |

12 (3) |

<0.001 |

After the Abortion I … |

|||

a) …felt everything related to the pregnancy was over |

269 (54) |

154 (42) |

0.109 |

d) …thought about the child I could have had |

248 (50) |

117 (32) |

<0.001 |

g) …didn’t want to think about it more |

175 (35) |

92 (15) |

0.005 |

b) …wished it was easier to talk about abortion |

164 (33) |

68 (18) |

<0.001 |

c) …wondered what happened to the foetus |

149 (30) |

45 (12) |

<0.001 |

f) …thought about the child as an angel |

75 (15) |

27 (7) |

<0.001 |

e) …wished I could go somewhere to mourn3 |

76 (15) |

19 (5) |

<0.001 |

Table 2 Existential attitudes in relation to induced abortion, 499 women* and 371 men**

Missing values: women* 2%-14%, men** 14%-24%.

The abortion experience takes place within a social network consisting mainly of the partner, friends, and caregivers. The support given by the partners or the caregivers was important, as it was for those being supportive to their partner. Others described how they felt desolate and lonely with their devastating feelings, for example “To feel how the baby slowly died after the first pill, bleeding out big chunks of the foetus was a very prevailing and difficult experience" (woman), and "The caregivers pretend that it is so easy and natural to have an abortion and talk about what happens in such clinical terms” (woman).

Both women and men displayed a wide variety of emotions and reactions to the abortion.

Some described they were mostly relieved after the abortion, ”Everything felt so wrong when I was pregnant. After the abortion everything felt fine, and I could go back to my life and focus on what I really want to do with my life” (woman). Others reported sadness and loss, and felt a continuing bond to the child that could have been, “A great sadness and loss. I had / have many thoughts on who he / she was. Who would it be? Will we meet in another life?” (Woman). One man reported: “Noted in my calendar the estimated birthday”, another man wrote “I am so sorry that we did not reach all the way in our discussions to keep the baby”. One woman expressed, “I was angry, sad, hurt, and alone. I had just killed the most beautiful thing that ever existed, my child”. Regardless of their feelings, most respondents demonstrated post-abortion that they coped with the situation, in their own individual way.

The aim of this study was to investigate existential attitudes appearing in relation to an induced abortion, among both women and men. Generally, the study highlighted the importance of addressing existential aspects in abortion care, when needed. About half of the women and a third of men reported spiritual beliefs. This distribution between women and men was similar to other studies of religiosity and spirituality.25,26

Men with spiritual beliefs had more need to ‘let off steam’, than those without spiritual beliefs. Women with spiritual beliefs had more need to do some act to grieve and thought more about the child as an angel than women without spiritual beliefs. Thus, spiritual beliefs might affect certain emotions and acts related to an abortion. According to the health care act2 and for increasing the quality of care, health care staffs are supposed to be open minded to conversations about spiritual and existential thoughts and concerns.

Men displayed existential thoughts, feelings, and needs related to abortion, although not to the same extent as women. The awareness of existential thoughts and needs in relation to an induced abortion is another important dimension for increasing women’s satisfaction with abortion care.27

Fertility awareness and decision induced abortion – a clinical procedure lined with existential aspects

For some women and men, the pregnancy was something positive in their lives, and to know they could conceive a pregnancy. However, along with fertility awareness, some reported fairness to never be able to be pregnant/conceive a pregnancy again, such as “what if, this was my last chance”. This ambivalence is a natural reaction after they have made the decision.28 Two-thirds of women and half of the men thought about their future and close relationships, suggesting the abortion procedure commonly related to a worldview beyond a clinical procedure and the physical condition. The abortion could be referred to as a life event evoking thoughts about their reproductive life.

During the abortion, both women and men described a need for responsiveness from partners, friends and relatives, and the attending staff. For women, spiritual beliefs were not associated with satisfaction of perceived attention by health care staff, however, spiritual beliefs in men were associated with dissatisfaction of the personnel treatment by health care staff. The personal attributes of the staff in attendance are important for care satisfaction among both women and men,12 and professionals themselves sometimes admit they neglect men.29 For some, an induced abortion could be referred to as a critical moment in life, where existential and spiritual concerns come to the surface, along with the need for nearness and support.23

Post abortion

Post-abortion, there were diverse feelings, described in terms of both relief and pride and loss and guilt, as previously has been found by Kero & Lalos.28

About half of women and men felt everything related to the pregnancy was over and expressed they wanted to continue with their lives as it was before the pregnancy and abortion. However, half of the women and a third of the men had continuing thoughts about the child they could have had. According to Swedish abortion law, it is the pregnant woman who has the right to decide on an abortion. This may place men in the position that they have to hide their emotions and obligate the women to give the impression they are “strong”, so as not to distress the woman any further. This might put pressure on a relationship to conceal one’s true feelings of grief, and needs to be addressed in abortion care. Conversely, during the pregnancy more women than men reported bonds and emotions to a child and had moral considerations about the abortion decision. However, research makes a strong case for the lack of psychological complications in women related to abortion.15

The male sample was not representative as it was selected through the women who invited the male partner to participate in the study. Therefore, the accurate response rate of the men could not be determined as it was unknown how many women actually gave the questionnaire to their male partners. Even though, this was the only way to reach the men involved in the abortion, it was reasonable to assume the sample was underrepresented by men not having an ongoing relationship with the pregnant women. As more men had an ongoing relationship than women, it was reasonable to assume a woman who had an ongoing relationship with the man involved was more motivated to forward the questionnaire to him, and that these men were more interested in participating. In addition, men with an ongoing relationship with the pregnant women may be more emotionally involved in the abortion process, and express this in their responses, than men without an ongoing relationship.

In the open answers and qualitative analysis, existential attitudes dominated. This might reflect that respondents experienced the abortion as challenging in some way and were more inclined to develop their answers. Despite the abortion raising existential thoughts, feelings and needs here and now, this study revealed nothing about the effects over time and its impact on everyday life. However, one long term follow-up describes the dominant post-abortion experience as a relief and a responsible act that did not affect everyday life.13,14

Legal, procedural, and institutional restrictions on safe abortion services, such as laws or policies forbidding the practice, are a major barrier for women worldwide. However, even when abortion services are legal, women face social and cultural barriers to accessing safe abortion services and preventing unintended pregnancies. Educational aspects can also present an obstacle, and interpersonal communication interventions, such as behavioral change efforts, as part of a broader education play an important role in overcoming these obstacles.3,30

Men and induced abortion has rarely been quantitatively explored. This study added new dimension to abortion research in that it highlighted men’s existential thoughts, feelings, and needs in connection to an induced abortion. Increased awareness of existential thoughts and needs in relation to an induced abortion within health care could improve satisfaction with abortion care among both women and men. However, beside safe medical care, staff may face difficulty in accommodating all types of strategies for addressing the variety of different needs in/within women and men with regard to spiritual and existential aspects. In Sweden, about 74% of women and half of men participating during the abortion procedure are satisfied with the care, and the personnel attention provided by staff is the most important factor for care-satisfaction.12

Men commonly displayed existential thoughts, feelings, and needs related to abortion, although not to the same extent as women. There was variation in existential attitudes and needs during an abortion procedure among women and men. This might challenge staff to be responsive to the variety of different existential needs. Nevertheless, in the professionals’ counseling and communication skills, there is scope for addressing existential aspects during the abortion procedure and also with respect to men’s needs.

Thanks to all the women who participated in our study, and all the providers involved in the study who remained committed and supportive, throughout. The study is a part of a center of excellence program at Uppsala University, Sweden: Impact of Religion: Challenges for Society, Law and Democracy. The project was supported by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS), the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (Project no 90147/11794), Uppsala-Örebro Regional Research Council (RFR-81551) and the Family Planning Fund at Uppsala University Hospital.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2017 Makenzius, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

International Universal Health Coverage Day is observed every year on December 12th to highlight the urgent need for affordable, quality health care for everyone. The 2025 theme is “Unaffordable health costs? We’re sick of it!”—a rallying cry to strengthen health systems and ensure no one is left behind. On this occasion, UHC supporters worldwide raise their voices to share the stories of millions still waiting for care. MedCrave Online Journal of Public Health welcomes researchers to contribute articles on the importance of health, offering a 40% discount on submissions to encourage knowledge-sharing and progress.

International Universal Health Coverage Day is observed every year on December 12th to highlight the urgent need for affordable, quality health care for everyone. The 2025 theme is “Unaffordable health costs? We’re sick of it!”—a rallying cry to strengthen health systems and ensure no one is left behind. On this occasion, UHC supporters worldwide raise their voices to share the stories of millions still waiting for care. MedCrave Online Journal of Public Health welcomes researchers to contribute articles on the importance of health, offering a 40% discount on submissions to encourage knowledge-sharing and progress.