MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 3

Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka

Correspondence: AA Nilanga Nishad, Ministry of Health, 122/a/3, Maharanugegoda, Ragama, Sri Lanka, Tel +0094718331470

Received: March 12, 2018 | Published: June 21, 2018

Citation: Nishad AAN, Wijesuriya CP, Sonnadara TT, et al. Immunization trends in Sri Lanka when the economic transition begins. MOJ Public Health. 2018;7(3):146?149. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2018.07.00220

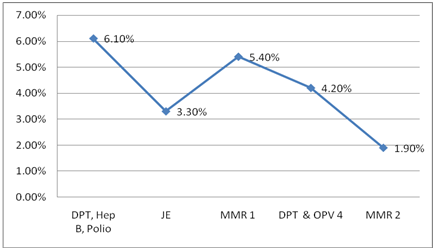

Nearly 100% coverage of Expanded Program of Immunization has a downward trend recently in Sri Lanka. Private sector immunization services seem to be the reason for this. This article tries to evaluate the rates of private sector immunizations (PSI) as well as to find reasons why people move into private sector even the government services are free. We calculated the prevalence of PSI in Biyagama Medical Officer of Health area and according to different antigens and interviewed parents attending to private sector to find the reasons why they prefer to go there with a self administered questionnaire in year 2014. Private sector immunization was defined as child immunized at private sector at least once other than BCG during the year 2014. There were 2941 Births in 2014. The rate of PSI in the area was 6% (5.6-6.4%). There was a full regional variation even within this 62 square kilometer area among 183,000 people. The highest prevalence was 6.1% (3-7) for the vaccinations at 2,4,6 months. Lower prevalence of the Japanese Encephalitis (3.3%) and Measles, mumps, and rubella-2 (1.9%) were observed. The common reasons for PSI were time constraints (63%) and rush at government centers (20%). But 90% of parents perceive that private sector vaccinations do not bear good responsibility. Government sector needs to improve some aspects of its vaccination program to maintain its quality at service delivery on the other hand private sector should arrange cold chain maintenance facilities, documentations so that they can prove the responsibility.

The Expanded program of immunization (EPI) was introduced to Sri Lanka in 1978. There onwards vaccine preventable disease burden had come down along a decent path. Incidences of diseases like polio, measles, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, and rubella declined rapidly over those years.1 Therefore, Sri Lanka has set the examples and had become popular when the world speaks about vaccine preventable diseases. Already established public health infrastructure around Public heath midwife since the eighteenth century coupled with a free health care delivery system to the grass root level might be the secret behind this success story. At the moment the EPI services are provided by the government sector, private hospitals, and general practitioners. The schedule for the first five years is BCG gave at birth, Diphtheria (D), Pertussis(P), Tetanus(T), Hepatitis B, Hemophilus Influenza-b (Hib) Oral polio vaccinations (OPV) at 2,4, and 6 months, Japanese Encephalitis (JE) at 9 months, Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) vaccinations at 12 months and at 3 years, DPT and OPV 4th dose at 18 months.1

Government sector vaccines are provided at field clinic centers by field health staff including medical officer of healths (MOH) and government hospital clinics. Private sector by main private hospitals in major cities and by general practitioners.2 Some people who have lack of time to attend to Maternal and Child Health clinic services provided by the government sector attend to those private vaccination providers who provide at more flexible times. Systematic review carried out in 2012 using 102 articles by Basu S et al.,3 in 2012 described that their findings do not support that the private sector is more efficient, accountable, or medically effective than the public sector, but the public sector appears frequently to lack timeliness and hospitality towards patients.3 Mills et al in 2002 reported that private sector lack expertise in provision of preventive health services.4 Aljunaid et al.,5 in 1996 mentioned that “Vaccines, in particular, require proper handling and storage, and private providers may fail to keep vaccines adequately refrigerated”. Further low- to middle-income non-fragile countries often have limited resources to allocate to immunization services. In addition, their ability to monitor private sector provision of services (e.g. the quality of service delivery), or a government’s stewardship over the private sector, is often limited due to insufficient financing and human resources.6

Although Sri Lanka reached nearly 100% coverage of EPI vaccinations within last ten years, there is a significant reduction of coverage in recent years. For example, DPT3 (Diphtheria, Pertussis and Tetanus 3rd dose) coverage which was 98% in 2007, has come nearly to 92% in 2010.7 Epidemiology unit in Sri Lanka has stated in their reports that one reason for this reduction might be the increase in private sector immunizations which lack reporting to the data bases at central level.2 The central government is providing the vaccines to private sector free of charge via regional health authorities. This statement can be proven by looking at coverage in Colombo and Gampaha where more private sector providers are available. But on the other hand, this might not be the truth since some districts like Monaragala, Puttalam, Nuwaraeliya, and Hambanthota also reported lower coverage where the private sector vaccination services are scarce.

While many international literature reviews have examined the role of the private sector in the provision of health services, studies done focusing immunization service provision is scarce.8,9 Therefore we wanted to find the prevalence of private sector immunization with the antigens and to evaluate why the government sector immunization services lost its popularity and what makes people go to the private sector for immunization of their children even when government provides free services. We selected Biyagama Medical Officer of Health (MOH) area size of 61.2 Square kilometers, situated in Gampaha the most populous district in the Country. The MOH area has a population of 183,000 and has 36 Public Health Midwife (PHM) areas. Western and southern parts of the MOH area lies adjacent to Colombo district. The people in the area are multiethnic, multicultural and have a vast socio-economic diversity. The area had 2941 births in 2014 and 14319 children under the age of 5 years in 2014.

We first calculated the prevalence of private sector immunization in the area with PHM birth and immunization registers, where they were advised to mark private-sector immunization in red color with letter "P" during the year 2014. We also interviewed 215 parents of children who were born after 1st of January 2009 with a self-administered questionnaire who are attending to the private sector for immunization. The survey did not include any personal identification details, and they were asked to put the short filled survey in a box. Data on child's immunization status, why they attend to the private sector and their perceptions about private sector immunizations were collected. The data collection was carried out in Biyagama Medical Officer of Health area in January 2015. A descriptive analysis was carried out quantitatively and qualitatively. Private sector immunization was defined as child immunized at private sector at least once other than BCG during the year 2014. Data were described with percentages and 95 percent confidence intervals.

There are 2941 Births in 2014. Altogether 215 infant’s parents were responded out of 230 disseminated questionnaires. Following table shows the distribution of a percentage of infants attending to the private sector for immunization (Table 1). The prevalence of private sector vaccination was relatively higher in areas which are more proximal to Colombo the capital and lower in areas more distal to Colombo. Higher prevalence areas and lower prevalent areas are clustered. The private sector vaccination is higher for the first three doses of DPT, Hepatitis B, and Polio vaccines. (6.1%, 95% CI 5.3 to 7%). There is a dramatic reduction for the Japanese Encephalitis (JEV) vaccine given at the age of 9 months of age (3.3%, 95% CI 2.7 to 4%) but MMR1 given at 12 months is again increased to 5.4% (95% CI 4.6 to 6.2%) and next two vaccinations decreases further (Table 2). Nearly 55% parents said they have time constrains which promote them to attend to the private sector for vaccinations. Government sector long ques came as the next leading reason (20%). More interestingly 10.5% parents attended to the private sector because they think government sector vaccines have more side effects than the private sector. Two percent believed that government vaccines are of poor quality (Table 3). Nearly 90% of parents perceive that private sector vaccinations do not bear right responsibility. They observed positive perceptions on quality of the vaccine given (61%), qualification of the vaccinator (69%) and experience of the vaccinator (73%).

PHM Area |

Number of under 5 children in care |

Number of children attending Private sector |

Percentage and 95% Confidence interval |

Mabima |

515 |

12 |

2.3(1.3- 4.0) |

Heiyanthuduwa South |

383 |

16 |

4.2(2.6-6.7) |

Pattiwila |

382 |

15 |

3.9(2.4-6.4) |

Walgama |

736 |

11 |

1.5(0.8-2.7) |

Meegahawatta |

400 |

8 |

2(1.0-3.9) |

Delgoda |

387 |

16 |

4.1(2.6-6.6) |

Malwana |

555 |

20 |

3.6(2.3-5.5) |

Nagahawatta |

351 |

4 |

1.1(0.4-2.9) |

Heiyanthuduwa North |

398 |

14 |

3.5(2.1-5.8) |

Heiyanthuduwa East |

335 |

7 |

2.1(1.0-4.4) |

Siyambalape North |

410 |

11 |

2.7(1.5-4.7) |

Araliya Uyana |

288 |

24 |

8.3(5.7-12.1) |

Rankethyaya |

360 |

41 |

11.4(8.5-15.1) |

Pahala Biyanwila West |

337 |

9 |

2.7(1.4-5.0) |

Henahatta |

428 |

6 |

1.4(0.6-3.0) |

Kadawatha |

253 |

44 |

17.4(13.2-22.5) |

Yatawatta |

285 |

7 |

2.5(1.2-5.0) |

Mawaramandiya |

459 |

19 |

4.1(2.7-6.4) |

Golummahara |

398 |

9 |

2.3(1.2-4.2) |

Kanduboda |

374 |

15 |

4(2.4-6.5) |

Biyagama |

506 |

32 |

6.3(4.5-8.8) |

Pahala Biyanwila East |

388 |

40 |

10.3(7.7-13.7) |

Ihala Biyanwila |

338 |

10 |

3(1.6-5.4) |

Sapugaskanda |

327 |

49 |

15(11.5-19.3) |

Makola Central |

451 |

37 |

8.2(6.0-11.1) |

Gonawala |

432 |

74 |

17.1(13.9-21.0) |

Pamunuwila |

388 |

61 |

15.7(12.4-19.7) |

Makola North |

387 |

37 |

9.6(7.0-12.9) |

Kurunduwatta |

513 |

48 |

9.4(7.1-12.3) |

Siyambalape South |

426 |

8 |

1.9(1.0-3.7) |

Wilahena |

277 |

31 |

11.2(8.0-15.4) |

Makola South |

319 |

61 |

19.1(15.2-23.8) |

Yatihena |

388 |

8 |

2.1(1.1-4.0) |

Siyambalapewatta |

352 |

10 |

2.8(1.5-5.5) |

Thalwatta |

510 |

39 |

7.6(5.6-10.3) |

Yabaraluwa |

283 |

8 |

2.8(1.4-5.5) |

Total |

14319 |

861 |

6(5.6-6.4) |

Table 1 Distribution of Under 5 children attending to the private sector for vaccination in Biyagama MOH area in 2014

Reason |

Number |

Percentage |

95% Confidence interval |

|

Difficult to find leaves |

69 |

34.5 |

27.9 |

43.8 |

Long ques at gov. sector |

40 |

20 |

14.5 |

27.8 |

Convenient times |

55 |

27.5 |

21.3 |

36.3 |

Not trusting gov. sector vaccines |

5 |

2.5 |

0.3 |

5.6 |

Gov. sector vaccines poor quality |

4 |

2 |

0.1 |

4.7 |

Work force low qualifications |

2 |

1 |

-0.4 |

3 |

Poor courtesy |

7 |

3.5 |

1 |

7.1 |

More side effects at gov. sector |

21 |

10.5 |

6.3 |

16.5 |

Good facilities at private sector |

12 |

6 |

2.7 |

10.7 |

Table 2 The reasons to attend to the private sector for vaccination of children a given by parents (n=215)

Percentage |

|||

Perceptions |

Good |

Bad |

Not known |

Quality of vaccine given in the private sector |

61 |

27.8 |

11.2 |

Qualification of the vaccinator |

69 |

20.o |

11 |

Experience of the vaccinator |

73 |

19 |

8 |

Parents education on vaccine and its effects |

39.3 |

32 |

28.7 |

Regarding the responsibility |

0 |

89.9 |

11.1 |

Table 3 Parents perception on private sector vaccination (n= 215)

The overall prevalence of private sector immunization in the area was 6% (5.6-6.4%). This value is less than that of in comparison to 28% reported in Colombo Municipal (CMC) area in 2007 by Agampodi SB and Amarasinghe DACL and 15% reported by Pan American Health Organization in 1996.2,10 Agampodi SB had collected data from a sample in CMC while we studied the whole population. There were big regional differences even throughout this small area. For example, Makola south and Kadawatha had a prevalence of 19.1% and 17.4% respectively. Nagahawatta and Henihatta had low prevalences such as 1.1% and 1.4% respectively. The most probable reason for this variability is the socio-demographic variability and access to the private sector in these areas. It is observed that the educational level and social class is higher among the parents of private sector immunization higher prevalence areas. The family size is also may be a matter of concern. The lower private sector immunizations areas tend to have higher family sizes with more Muslim communities too. The other interesting trend observed is the declining of prevalence with the advancement of the age of the child and with different antigens. There is a steep decline observed from vaccines at ages of 2,4,6 months to JE vaccine, but the MMR1 and DT has a little higher value than this (Graph 1). This may be due to unavailability of single dose JE vaccine at most of the private sector centers. Most of the private sector centers provide a Hexavalent instead of Pentavalent and Oral polio vaccination provided at government sector. But the prevalence of MMR2 vaccine given at three years has become the lowest. Cost may be a factor that causes a reduction in the prevalence of private sector vaccinations when the child gets older. Even-though again we have not studied the vaccine given at the age of 5 and 12 in this study, we observed a lower prevalence of both vaccinations.

Graph 1 Line diagram to show the trend of Private sector vaccination percentage with the advancement of the age of the child.

In an analysis of the reasons why these people are attending to the private sector for vaccinations, the increase in private sector deliveries, increase in the access such as expanding private sector and access due to increase in purchasing power may be the reasons. Time constrains also become a major reason when it comes to working parents. Since it is a kind of health-seeking behavior, it also depends on various factors such as beliefs, attitudes and peer pressures. Vaccination also has become a social event and therefore it is a complex phenomenon to describe why they attend to the private sector because still, some rich parents are attending to government sector due to the trust they have on government sector more than on private sector. On the other hand, people are not aware of the real evaluation criteria to sort out the quality of vaccines such as cold chain maintenance. People attending to the private sector were not sure about the responsibility of vaccination at private sector although they perceive positively on vaccine and vaccinator.

On the other hand, health sector officials are still not aware of the cold chain maintenance at the private sector, and some local authorities who had started giving away the vaccines to the private sector for immunization have again decided to stop it due to cold chain issues and not giving the information returns. There are no proper channels of returns to the central authority from the private sector at the moment. Therefore we are not sure about the quality of the vaccine received by the client up to date, and we may need to carry out seroprevalence studies. Another dangerous issue arising is that there are reported incidences of violation or alteration of EPI schedule without justifiable reasons just for the client’s requests. Further, the government sector needs to improve some aspects of its vaccination program to maintain its quality at service delivery, such as an increase in the accessibility for convenient times for parents and social marketing to dispel misconceptions like “poor quality vaccines of the government sector." At the same time, the private sector should arrange cold chain maintenance facilities, documentation. They also try to prove that they offer responsible services to the public.

We would like to acknowledge Public health nursing sisters Ramanayake, Chandrani, Susilawathi and all the public health midwives in Biyagama area.

Authors have no any conflicts of interests or no funding for the work.

©2018 Nishad, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.