MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Research Article Volume 14 Issue 2

1Asella Teaching and Referral Hospital, Asella City, Ethiopia

2Arsi University College of Health Science Department of Public Health Asella city, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Melese Tadesse, Arsi University College of Health Science Department of Public Health, Asella city, Ethiopia, Tel +251913976496

Received: June 02, 2025 | Published: July 16, 2025

Citation: Abey N, Ballo S, Aredo MT. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety practices among health care professionals of Asella town in year 2025 G.C. MOJ Public Health. 2025;14(2):175-184. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2025.14.00487

Background: Preventing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) is essential for delivering safe and high-quality healthcare services. Globally, HAIs remain a significant public health concern, contributing to increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. Although many of these infections are preventable through cost-effective infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, healthcare facilities in sub-Saharan Africa often lack effective IPC programs. In Ethiopia, limited data exist on healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding infection prevention and patient safety.

Objective: To assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice of infection prevention and patient safety among healthcare professionals in public health facilities in Asella town, Ethiopia, in 2025.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from February 7 to March 20, 2025, among healthcare professionals working in Asella public health facilities. Participants were selected using simple random sampling. Data were collected using a standardized, pre-tested questionnaire. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Arsi University Ethics Committee, and formal permission was secured from the respective health facilities.

Results: The study found that healthcare professionals’ knowledge of infection prevention was significantly associated with educational level (AOR = 3.248; 95% CI: 1.360–7.759), type of hospital (AOR = 0.304; 95% CI: 0.102–0.906), and the availability of bathing facilities (AOR = 0.101; 95% CI: 0.011–0.974).

Conclusion: Educational level, hospital type, and the availability of bathing facilities are key factors influencing healthcare professionals’ knowledge and practices regarding infection prevention and patient safety. Strengthening IPC programs and addressing infrastructure gaps at the facility level may improve compliance and safety outcomes. Policy efforts should focus on institutionalizing regular IPC training and upgrading basic hygiene infrastructure across all public health facilities.

Keywords: infection prevention, patient safety, healthcare-associated infections, healthcare professionals, Ethiopia, knowledge attitude practice (KAP)

Background of the Study

Infection prevention plays a crucial role in reducing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), which are the most common adverse events in healthcare globally. HAIs can occur endemically or epidemically, impacting the quality of care for hundreds of millions of patients annually in both developed and developing countries.1 HAIs are defined as localized or systemic conditions resulting from adverse reactions to infectious agents or toxins acquired in healthcare settings, which were neither incubating nor symptomatic at admission.1

HAIs have become a significant global public health concern, posing serious risks to patients and healthcare workers. They contribute to increased morbidity, mortality, antimicrobial resistance, prolonged hospital stays, and substantial economic burdens on healthcare systems.2 The spectrum of HAIs ranges from mild infections like upper respiratory tract infections to severe complications such as post-operative wound infections. Surgical site infections are notably the most common in developing countries, affecting up to two-thirds of operated patients.3 Immunocompromised individuals, such as those with AIDS, are particularly vulnerable to HAIs.4

The burden of HAIs in Ethiopia and other developing countries is reported to be high, largely due to overcrowded facilities, insufficient staff, and poor compliance with infection prevention and control measures.5 In intensive care units, HAIs affect about 51% of patients in developed countries and between 4.4% and 88.9% in developing countries, although the true magnitude in low-income settings is often underestimated due to inadequate surveillance systems.6 A study in an Ethiopian tertiary hospital reported an overall HAI incidence of 28.15 per 1000 patient days, with the highest rates in ICU patients (207.6 per 1000 patient days). Urinary tract infections (68.71%) and surgical site infections (28.72%) were the most frequent HAIs documented.6 The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the critical need for patient safety standards to help hospitals assess and improve care quality, build staff capacity in patient safety, and engage patients in health safety improvements.7

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly transformed IPC training through the adoption of e-learning and simulation-based education, which improved both knowledge retention and compliance among healthcare workers.8

Research indicates that unintended patient harm occurs in approximately 10% of inpatient admissions, with around 75% of these incidents preventable. The WHO Patient Safety Assessment Manual estimates that 5–10% of healthcare expenditures are attributable to unsafe practices causing patient harm, most of which result from systemic failures rather than individual errors.5

The conducted a global survey and reported that post-pandemic IPC training programs that combined online and on-site learning were associated with higher healthcare worker compliance and reduced healthcare-associated infections.9

The countries that implementing continuous, mandatory IPC training after COVID-19—especially those integrating behavior change communication—achieved improved adherence to hand hygiene, PPE use, and patient safety practices.10

Globally, a significant number of healthcare workers and patients acquire HAIs annually, contributing to mortality, prolonged hospital stays, and the rise of multidrug-resistant organisms driven by antibiotic overuse. Most HAIs are preventable through simple, cost-effective strategies. In resource-limited settings, inadequate infection prevention exacerbates the risk of emerging and re-emerging infections among healthcare providers and patients.

In Ethiopia, the Federal Ministry of Health prioritizes infection prevention by implementing guidelines tailored for resource-limited environments to improve patient safety and reduce HAIs. Identifying infection types, sources, and contributing factors is critical for developing effective, evidence-based interventions to protect both patients and healthcare workers in Ethiopian healthcare settings.

A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) towards infection prevention and control among healthcare professionals in Asella.

Study area and period

The study took place in public health facilities in Asella Town, Arsi Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Data collection occurred from February 7 to March 20, 2025. Asella is the administrative center of Arsi Zone, located approximately 159 km from Addis Ababa at coordinates 7°57′N latitude and 39°7′60″E longitude, with an elevation of 2,430 meters above sea level.

Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional design was employed. Healthcare professionals including nurses, midwives, and laboratory technicians working daytime shifts were randomly selected. Approximately one-third of professionals from each category participated by completing a self-administered questionnaire via a smartphone-based software, Kobo Toolbox.

Source population

All of the health care professionals in Asella public health facilities in the Year 2025 G.C. (Table 1)

|

Health worker category |

Number of HWF by facility |

||

|

Asella health center |

Halal health center |

Asella specialized referral hospital |

|

|

Specialist Medical Doctor |

|

|

100 |

|

Medical Doctor |

2 |

1 |

20 |

|

Health Officer |

9 |

5 |

11 |

|

Nurse |

24 |

14 |

215 |

|

Surgical Officer |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Radiologist |

1 |

10 |

|

|

Anesthetist |

2 |

26 |

|

|

Midwife |

8 |

5 |

74 |

|

Laboratory Technologist |

4 |

4 |

55 |

|

Pharmacist |

6 |

4 |

44 |

|

Environmental Health Officer |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Urban Health Extension Worker |

15 |

12 |

|

|

Other Health Professionals |

|

|

41 |

|

Total |

95 |

46 |

596 |

Table 1 Distribution of health workforce in public health facilities, Asella, Ethiopia

Study population

The study population included all healthcare professionals—nurses, midwives, and laboratory technicians—working in Asella public health facilities during the study period. Eligible healthcare professionals working at Asella Teaching and Referral Specialized Hospital and two public health centers in Asella Town, who were considered potentially high-risk, were included in the study.

Nurses comprised the largest group, with the majority (85.0%) based at Asella Specialized Referral Hospital. The remaining nurses were distributed across Asella Health Center (9.5%) and Halal Health Center (5.5%), reflecting a strong reliance on the referral hospital for nursing services. Similarly, most midwives (85.1%) worked at Asella Specialized Referral Hospital, while smaller proportions were based at Asella Health Center (9.2%) and Halal Health Center (5.7%), indicating a concentration of midwifery services at the referral hospital. Laboratory professionals were also predominantly stationed at Asella Specialized Referral Hospital, which accounted for 87.3% of this workforce. Both Asella Health Center and Halal Health Center each housed 6.3% of laboratory staff, underscoring the referral hospital’s key role in providing laboratory services.

Sampling technique and sample size

A stratified random sampling method was employed healthcare professionals was stratified into three professional groups: nurses, midwives, and laboratory technicians. A proportional sample was drawn from each group based on their representation in the total population.

Using a 95% confidence level, a 5% margin of error, and a 74% prevalence of adequate infection prevention practices (based on previous studies), the sample size was calculated as 232 after adjusting for a 10% non-response rate.

n = (Z² * P * (1 - P)) / d²

Where:

Z = 1.96 (critical value for 95% confidence)

P = 0.74 (proportion of healthcare professionals with adequate infection prevention practices, based on previous studies)

d = 0.05 (margin of error).

The initial sample size (n) was calculated as 296. Since the source population is less than 10,000, a correction formula was applied:

nf = n / [1 + (n - 1) / N]

Where:

N = total healthcare professionals population (737).

The corrected sample size (nf) is 212. Adjusting for a 10% non-response rate, the final sample size is 232.

From the total 232 participants 186, 30, 16 participants was selected proportionally from Asella Specialized Hospital, Asella Health Center and Halila Health center.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Participants were included if they met all of the following:

Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded if they met any of the following:

Variables

Independent variables

Dependent variables

Justification for choosing the KAP model

The KAP model was chosen because it is a widely recognized framework in public health research for assessing and understanding the relationship between what individuals know (knowledge), how they feel (attitudes), and how they act (practices) in specific health contexts. In the case of infection prevention and patient safety, this model is particularly relevant as it helps to identify knowledge gaps, negative attitudes, and unsafe practices among healthcare professionals, thereby informing targeted interventions and policy recommendations. Its structured approach supports the development of behavior change strategies that are essential for improving compliance with infection prevention and control measures.

Data collection method

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire developed in English and programmed into Kobo Toolbox. The questionnaire included sections on socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding infection prevention and patient safety. Two public health students conducted face-to-face interviews, and data quality was overseen by a supervisor.

Data quality control

Data collectors received orientation and training to reduce errors related to skill or knowledge gaps. The supervisor conducted frequent checks during data collection to ensure completeness and consistency. Any errors detected were corrected immediately. After collection, the principal investigator reviewed the data for completeness and quality at entry, analysis, and interpretation stages.

Data processing, analysis, and interpretation

Data were cleaned, edited, compiled, and organized using SPSS version 25. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess associations between dependent and independent variables. Results were presented using text, tables, graphs, and charts, and interpreted to provide relevant conclusions.

Operational definitions

Categorization

Attitude: HCWs’ perceptions, feelings, beliefs, and level of agreement or disagreement regarding the importance and necessity of infection prevention and patient safety practices in their daily routines.

Categorization

Measurement: Practice will be assessed using an observational checklist and self-reported behaviors in a questionnaire. The checklist will include items such as:

Scoring system

Categorization

The research proposal was submitted to the Department of Public Health at Arsi University College of Health Sciences for ethical review. Following approval, an official letter was obtained from the department head and submitted to the Asella Town Health Office to secure cooperation and permission. The study’s purpose and objectives were clearly explained to all participants prior to data collection, and informed consent was obtained. Participation was entirely voluntary, and participants were informed of their right to refuse or withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

The majority of respondents (60.8%) were aged 35–44 years, with females comprising 59.5% of the sample. Nurses represented the largest professional group (55.6%), followed by midwives (24.6%) and laboratory professionals (19.8%). Most participants (80.2%) worked at teaching and referral hospitals, and nearly all (94.8%) were married.

Institutional readiness for infection prevention and control (IPC) was notably high. All respondents reported the presence of infection prevention guidelines and functional IPC committees in their facilities (100%). Availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) was nearly universal (99.6%), and regular supervision was consistently reported (100%). Access to continuous drinking water was reported by 94% of participants, with 87.9% having access to bathing facilities. All facilities had proper waste disposal systems, including fenced placental pits, incinerators, and clear disposal mechanisms. Waste disposal was mainly conducted through incineration (48.7%) and burning (51.3%), with infectious and sharp wastes being the most commonly managed types (45.7%). (Table 2)

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Age group (years) |

24–34 |

44 |

19 |

|

35–44 |

141 |

60.8 |

|

|

45–54 |

39 |

16.8 |

|

|

≥55 |

8 |

3.4 |

|

|

Sex |

Male |

94 |

40.5 |

|

Female |

138 |

59.5 |

|

|

Profession |

Laboratory |

46 |

19.8 |

|

Nurse |

129 |

55.6 |

|

|

Midwifery |

57 |

24.6 |

|

|

Type of health institution |

Health Center |

46 |

19.8 |

|

Teaching and Referral Hospital |

186 |

80.2 |

|

|

Marital status |

Single |

12 |

5.2 |

|

Married |

220 |

94.8 |

|

|

IPC guidelines available |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Functional IPC committee |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Regular IPC supervision |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Available PPE in facility |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Sufficient PPE supplies |

Yes |

231 |

99.6 |

|

No |

1 |

0.4 |

|

|

Continuous drinking water |

Yes |

218 |

94 |

|

No |

14 |

6 |

|

|

Bathing facilities |

Yes |

204 |

87.9 |

|

No |

28 |

12.1 |

|

|

Fenced placental pit |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Functional incinerator |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Waste disposal system |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Method of waste disposal |

Burning |

119 |

51.3 |

|

Incinerator |

113 |

48.7 |

Table 2 Sociodemographic Characteristics and Institutional IPC Readiness of Respondents (n = 232) of the study respondent in a study of knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety among health care professionals in Asella town, Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia

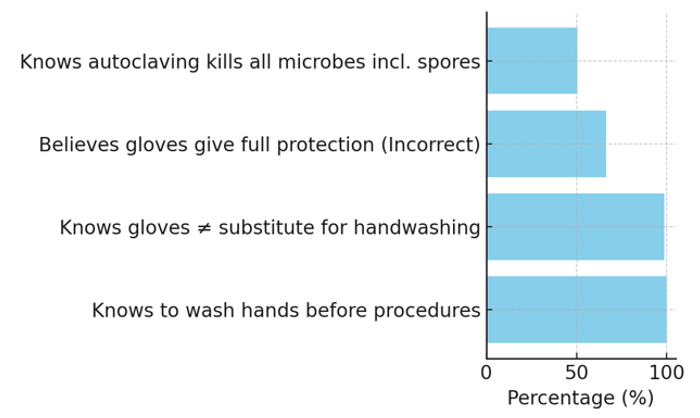

Knowledge levels were high across most domains. All participants (100%) reported awareness of infection prevention principles, the impact of healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs), and the importance of disinfection, standard precautions, and hand hygiene in preventing transmission.

However, significant gaps were identified. Only 50.4% correctly understood that autoclaving eliminates all microorganisms, including spores, indicating a critical knowledge deficit. Additionally, 9% of respondents were unaware that nosocomial infections can be transmitted through contaminated medical equipment.

Misconceptions regarding personal protective equipment (PPE) were also noted. Over half (54.7%) believed that masks and goggles were unnecessary during potential exposure to blood or body fluids, and 66.4% mistakenly believed that gloves alone offer complete protection against infection.

(Table 3)

|

Item |

Category |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Heard about infection prevention principles |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Aware of HCAIs impact on clinical outcomes |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Disinfection prevents HCAIs |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Know HCAIs can be transmitted via medical equipment |

Yes |

230 |

99.1 |

|

No |

2 |

0.9 |

|

|

Know transmission via blood/body fluids |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Know when to apply standard precautions |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Autoclaving destroys all microorganisms including spores |

Yes |

117 |

50.4 |

|

No |

115 |

49.6 |

|

|

Handwashing reduces healthcare infection risk |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Alcohol-based antiseptic = soap & water if hands are not visibly dirty |

Yes |

230 |

99.1 |

|

No |

2 |

0.9 |

|

|

Masks and goggles unnecessary for blood exposure risk |

Yes (Incorrect) |

127 |

54.7 |

|

No (Correct) |

105 |

45.3 |

|

|

Gloves provide complete protection |

Yes (Incorrect) |

154 |

66.4 |

|

No (Correct) |

78 |

33.6 |

|

|

Gloves should be worn if fluid exposure is anticipated |

Yes |

227 |

97.8 |

|

No |

5 |

2.2 |

|

|

Gloves as substitute for handwashing |

Yes (Incorrect) |

3 |

1.3 |

|

No (Correct) |

229 |

98.7 |

|

|

Handwashing before procedures |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

Table 3 Knowledge on Infection Prevention Among Healthcare Workers (n = 232) in the study of knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety among health care professionals in Asella town, Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2025

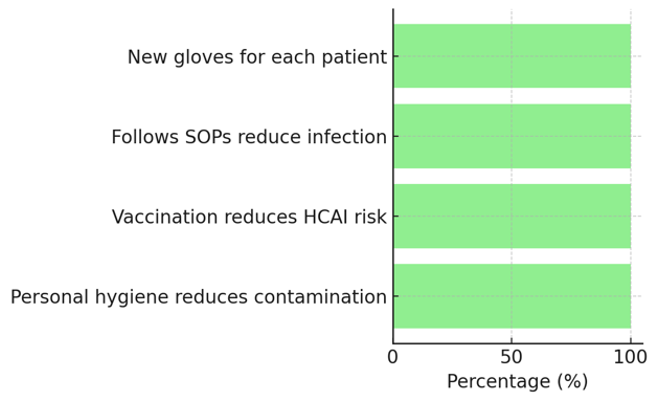

Attitudes toward infection prevention and control (IPC) practices were overwhelmingly positive. All respondents agreed that using new gloves for each patient, adhering to standard operating procedures (SOPs), maintaining personal hygiene, and receiving vaccinations or prophylaxis significantly reduce the risk of hospital-acquired infections.

Nearly all participants (99.1%) also agreed that decontaminating equipment with 10% sodium hypochlorite for 10 minutes is sufficient for effective disinfection.

This high level of consensus reflects strong internal motivation among healthcare professionals to comply with IPC measures and to maintain a safe environment for both patients and healthcare staff.

(Table 4)

|

Item |

Response |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

New gloves for each patient |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

SOPs reduce contamination risk |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Decontaminating with 10% sodium hypochlorite for 10 minutes is adequate |

Agree |

230 |

99.1 |

|

Disagree |

2 |

0.9 |

|

|

Vaccination reduces HCAI risk |

Agree |

232 |

100 |

|

Prophylaxis reduces HCAI risk |

Agree |

232 |

100 |

|

Good personal hygiene reduces contamination risk |

Agree |

232 |

100 |

Table 4 Attitudes Toward Infection Prevention (n = 232) of the study respondents in the study of knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety among health care professionals in Asella town, , Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2025

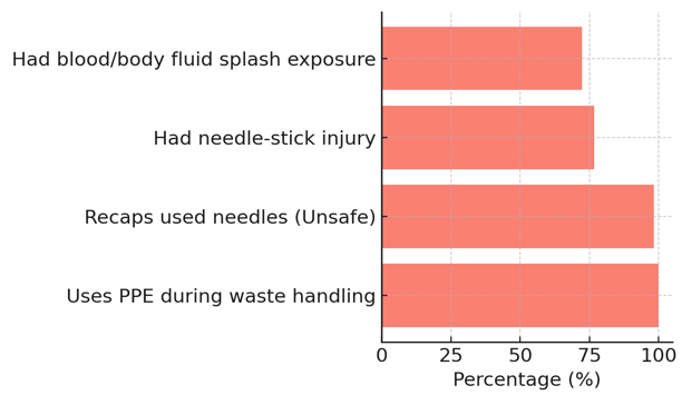

Despite high levels of knowledge and positive attitudes, actual infection prevention and control (IPC) practices revealed some concerning trends. While all respondents reported receiving the Hepatitis B vaccine and using protective devices during waste handling, a significant proportion had encountered occupational hazards: 72.4% had experienced splashes of blood or body fluids, and 76.7% had sustained needle-stick injuries—highlighting substantial exposure risks.

Most notably, 98.3% of respondents reported recapping used needles before disposal, a widely recognized unsafe practice that increases the risk of needle-stick injuries.

On a more positive note, all participants confirmed the availability of written waste disposal guidelines. Additionally, 100% reported that hazardous and nonhazardous waste were collected separately and that personal protective equipment was consistently used during waste handling.

(Table 5)

|

Item |

Category |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Received Hepatitis B vaccination |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Ever experienced splash of blood/body fluids |

Yes |

168 |

72.4 |

|

No |

64 |

27.6 |

|

|

Ever experienced needle-stick injuries |

Yes |

178 |

76.7 |

|

No |

54 |

23.3 |

|

|

Hazardous/nonhazardous waste separated |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Use PPE during waste handling |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

|

Recap used needles before disposal |

Yes (Unsafe) |

228 |

98.3 |

|

No (Safe practice) |

4 |

1.7 |

|

|

Written guideline for waste disposal available |

Yes |

232 |

100 |

Table 5 Infection Prevention Practices Among Healthcare Workers (n = 232) in the study of knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety among health care professionals in Asella town, , Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2025

Visual representations of KAP distribution

Figure 1–Figure3

Figure 1 Knowledge distribution. illustrates healthcare workers' knowledge on key IPC concepts, highlighting misconceptions around glove use and sterilization in the study of knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety among health care professionals in Asella town, , Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2025.

Figure 2 Attitude distribution shows the uniformly positive attitudes among respondents toward IPC practices, such as SOPs, vaccination, and hygiene in the study of knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety among health care professionals in Asella town, , Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2025.

Figure 3 Practice distribution reveals concerning levels of unsafe practices (e.g., needle recapping) and occupational exposure, despite high reported PPE use in the study of knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety among health care professionals in Asella town, , Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2025.

Associated factors of knowledge, attitude, and practice towards infection prevention and patient safety among healthcare professionals in Asella Town

This study assessed factors associated with healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) towards infection prevention and patient safety using both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Only variables found to be statistically significant or potentially influential were retained in the final models.

The factors significantly associated with knowledge were educational level, type of facility, and availability of bathing facilities.

Educational level

Compared to participants with a Laboratory background (reference group), those with a Midwifery education were:

Similarly, participants with a Nursing background were:

Type of facility

Those working in teaching and referral hospitals were 88.9% less likely to have good knowledge compared to those in primary hospitals:

This indicates a significant inverse association, suggesting better knowledge among healthcare workers at primary hospitals.

Availability of bathing facilities

Availability of bathing facilities was positively associated with better knowledge:

This shows a statistically significant relationship (p < 0.05), indicating that access to bathing facilities may support improved awareness and practices related to infection prevention.

Factors associated with good practice included sex, educational level, type of hospital, and availability of drinking water.

Educational level

Compared to laboratory professionals, nurses were significantly more likely to demonstrate good practice:

AOR = 0.425, 95% CI: 0.208–0.871

This suggests nurses had 57.5% reduced odds of poor practice, possibly due to greater exposure to IPC training.

Midwifery professionals, however, did not show a statistically significant difference in practice:

AOR = 1.089, 95% CI: 0.481–2.464

Type of facility

Participants working in teaching and referral hospitals had significantly better practice scores compared to those in health centers:

AOR = 0.331, 95% CI: 0.140–0.784

This indicates a 66.9% reduced odds of poor practice among those at referral institutions.

Availability of drinking water

In the bivariate analysis, the availability of adequate and continuous drinking water was significantly associated with good practice:

COR = 0.244, 95% CI: 0.066–0.900

However, this association was not retained in the multivariate analysis, suggesting that other factors may have explained the relationship.

|

Category |

Variable |

Knowledgeable |

COR |

AOR |

|

|

Your educational level |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

|||

|

Laboratory |

15(32.6) |

31(67.4) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Midwifery |

35(61.4) |

22(38.6) |

3.29(1.455-7.429)* |

3.248(1.360-7.759)* |

|

|

Nurse |

73(56.6) |

56(43.4) |

2.696(1.327-5.469) |

2.514(1.176-5.375)* |

|

|

Type of Hospital |

Primary Hospital |

40(87) |

6(13) |

1 |

1 |

|

Teaching and referral hospital |

83(44.6) |

103(55.4) |

0.121(0.049-0.299)* |

0.304(0.102-0.906)* |

|

|

Availability of bathing facilities |

No |

27(96.4) |

1(3.6) |

1 |

1 |

|

Yes |

96(47) |

108(53) |

0.033(0.004-0.247)* |

0.101(0.011-0.974)* |

|

Table 6 Only Candidate variables for bivariate and multivariate of knowledge

*=p<0.05, 1= Indicator of reference, COR=Crude Odds Ratio, AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio

|

Category |

Variable |

Practice |

COR |

AOR |

|

|

Poor practice |

Good practice |

||||

|

Sex |

Female |

78(56.5) |

60(43.5) |

1 |

|

|

Male |

36(38.3) |

58(61.7) |

0.477(0.280-0.815)* |

|

|

|

Your educational level |

Laboratory |

27(58.7) |

19(41.3) |

1 |

1 |

|

Midwifery |

35(61.4) |

22(38.6) |

1.120(0.507-2.474) |

1.089(0.481-2.464) |

|

|

Nurse |

52(40.3) |

77(59.7) |

0.475(0.240-0.942)* |

0.425(0.208-0.871)* |

|

|

Type of Hospital |

Primary Hospital |

33(71.7) |

13(28.3) |

1 |

1 |

|

Teaching and referral Hospital |

81(43.5) |

105(56.5) |

0.404(0.150-0.615)* |

0.331(0.140-0.784)* |

|

|

Is there enough and continuous available drinking water |

No |

11(78.6) |

3(21.4) |

1 |

|

|

Yes |

103(47.2) |

115(52.8) |

0.244(0.066-0.900)* |

||

Table 7 Only Candidate variables for Bivariate and Multivariate of knowledge, attitude and practice of study participants

*=p<0.05, 1= Indicator of reference, COR=Crude Odds Ratio, AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio

The study revealed that most healthcare professionals had positive attitudes and high levels of knowledge about infection prevention and patient safety, particularly regarding hand hygiene, standard precautions, and the impact of healthcare-associated infections. Institutional readiness was strong, with nearly all facilities equipped with functional IPC committees, PPE, and proper waste management systems. However, notable knowledge gaps existed, particularly concerning the effectiveness of autoclaving and the proper use of PPE. Despite positive attitudes, unsafe practices like needle recapping (98.3%) and high exposure to needle-stick injuries (76.7%) and blood/body fluid splashes (72.4%) were common. Multivariate analysis identified educational level, type of health facility, and access to infrastructure (e.g., bathing facilities, drinking water) as significant factors influencing knowledge and practice.

Knowledge

The study found that healthcare professionals in Asella public health facilities demonstrated commendably high general awareness of infection prevention and control (IPC) concepts. All participants were familiar with infection prevention principles, understood the importance of hand hygiene, and acknowledged the role of disinfection and standard precautions in preventing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). These findings are consistent with studies conducted in West Arsi, Addis Ababa, and Debre Markos, where similarly high levels of IPC awareness were reported among healthcare providers [8, 9]. This alignment suggests that national training efforts and policy dissemination—such as the Federal Ministry of Health’s infection prevention guidelines—have achieved substantial reach in promoting general awareness.

Despite this encouraging baseline, the study identified critical knowledge gaps in specific areas. Nearly half of the respondents (49.6%) did not know that autoclaving destroys all microorganisms, including spores—highlighting a limited understanding of sterilization standards. Additionally, 9% of healthcare workers failed to recognize contaminated medical equipment as a transmission route for nosocomial infections, which is particularly concerning in high-risk settings such as surgical and laboratory departments. Misconceptions were also evident regarding personal protective equipment (PPE) use. For example, 54.7% of participants believed that masks and goggles were unnecessary during procedures with potential exposure to blood or body fluids, and 66.4% incorrectly assumed that gloves alone offer complete protection from infection.

These findings underscore the need for more targeted, competency-based training programs that extend beyond theoretical knowledge. Such programs should emphasize practical application and directly address common misconceptions to strengthen IPC compliance and effectiveness in clinical settings.

The study revealed overwhelmingly positive attitudes toward infection prevention and patient safety among healthcare professionals in Asella public health facilities. All participants affirmed the importance of using a new pair of gloves for each patient, adhering to standard operating procedures (SOPs), maintaining personal hygiene, and receiving vaccinations and prophylaxis to reduce the risk of hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). Nearly all respondents (99.1%) agreed that decontaminating equipment with 10% sodium hypochlorite for 10 minutes is adequate for disinfection.

These findings indicate that healthcare workers not only recognize the critical role of standard precautions in infection prevention but also view these practices as essential to ensuring safe patient care. The high level of agreement reflects strong internal motivation and professional commitment to upholding infection control standards—a finding consistent with previous studies in Ethiopia and other settings.11,12

Such positive attitudes are fundamental for fostering sustainable behavioral change in healthcare environments. Attitudinal commitment often precedes or reinforces behavioral compliance, especially when bolstered by institutional policies and leadership support. However, it is important to note that these positive attitudes did not always translate into safe practices. For instance, despite near-universal acknowledgment of the importance of SOPs and PPE use, 98.3% of respondents still reported recapping needles—a well-known unsafe practice.

This discrepancy between attitude and behavior highlights the complex relationship between belief and action. It suggests that structural barriers, entrenched habits, or insufficient oversight may hinder the practical application of these positive attitudes in daily clinical routines. Therefore, while fostering and sustaining positive attitudes is essential, it must be coupled with systemic interventions, practical skills training, and accountability mechanisms to ensure consistent adherence to safe practices.

The results of this study underscore a concerning gap between healthcare professionals’ knowledge and attitudes and their actual clinical practices. Although all respondents reported access to protective equipment and infection prevention guidelines, their behaviors did not consistently reflect safe infection control practices. Most notably, 98.3% admitted to recapping used needles—an outdated and discouraged practice due to its strong association with needle stick injuries and the transmission of blood borne infections.

This concern is further supported by the high incidence of occupational exposure: 76.7% of respondents reported experiencing needle-stick injuries, and 72.4% reported being splashed with blood or body fluids during the course of their work. These findings are consistent with previous studies conducted in Ethiopia, which have shown that unsafe handling of sharps remains a persistent hazard despite IPC awareness efforts.13,14

On a more positive note, the study identified areas of strong compliance. All participants had received the Hepatitis B vaccine and confirmed the use of protective devices during waste handling. Moreover, all health facilities involved in the study had established functional infection prevention and patient safety (IPPS) committees, as well as essential infrastructure such as fenced placental pits, incinerators, and systems for segregating hazardous and non-hazardous waste.

These strengths indicate that the institutional framework and resources for infection control are largely in place. However, the persistence of risky practices suggests that behavior change requires more than just the provision of materials and policies. Continuous professional reinforcement, hands-on mentoring, and supportive supervision are necessary to bridge the gap between knowledge, attitude, and practice and to ensure safer healthcare environments.

Multivariate regression analysis identified several factors significantly associated with healthcare workers’ knowledge and practices regarding infection prevention and control (IPC). Educational level emerged as a key determinant of knowledge: midwives and nurses were significantly more likely to demonstrate good knowledge compared to laboratory professionals. This suggests that existing training programs may be better integrated into nursing and midwifery curricula, highlighting the need to enhance IPC content within laboratory science education.

Interestingly, healthcare workers in teaching and referral hospitals were significantly less likely to possess good knowledge and engage in safe practices compared to those in primary hospitals. This somewhat unexpected finding may be attributed to factors such as increased workload, staff fatigue, or limited access to practical, hands-on training in more complex healthcare environments.

Infrastructure also played a critical enabling role. The availability of bathing facilities and continuous access to drinking water were both positively associated with higher levels of IPC knowledge and safer practices. These findings are consistent with global evidence, including guidance from the WHO, which emphasizes the foundational importance of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services in supporting effective infection prevention programs.14,15

Moreover, gender differences were observed: male respondents were less likely to demonstrate good IPC practices compared to their female counterparts. This finding suggests the potential value of incorporating gender-sensitive approaches into behavior change interventions.

Overall, these results underscore the need for both individual- and system-level strategies to bridge the gap between knowledge, attitudes, and consistent, safe clinical practices. Addressing educational disparities, strengthening WASH infrastructure, and tailoring interventions to account for contextual and demographic differences will be essential to achieving sustained improvements in IPC compliance.16

This study revealed that healthcare professionals in Asella public health facilities possess generally good knowledge and positive attitudes towards infection prevention and patient safety. However, critical knowledge gaps—particularly around sterilization methods and personal protective equipment—were identified. Moreover, unsafe practices such as needle recapping and high rates of occupational exposure persist despite the availability of PPE and IPC guidelines.

Addressing these gaps through targeted interventions could substantially reduce healthcare-associated infections, enhance patient safety, and improve the occupational health of healthcare workers.

First of all, we would like to thank Arsi University College of health sciences, department of public health for facilitating to conduct this research. Second our special thanks go to our colleagues for their unreserved constructive comment and guidance throughout our research work.

Authors' contributions

NA=Original draft preparation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, data curation, SB=Original draft preparation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation data, MTA= Conceptualization, Methodology, Analysis, data curation

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Arsi University ethical review board approved the study. Issues of rights, privacy, and confidentiality ensured during data collection period. Participants had the right to participate or not and to withdraw at any time when they feel discomfort.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2025 Abey, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.