MOJ

eISSN: 2374-6939

Case Report Volume 4 Issue 3

Department of Orthopaedics, General Hospital of Attica Sismanogleio Amalia Fleming, Greece

Correspondence: Soukakos K Panagiotis, Department of Orthopaedic, General Hospital of Attica Sismanogleio Amalia Fleming, Greece

Received: December 21, 2016 | Published: February 3, 2016

Citation: Adamopoulos AP, Gavras M, Soukakos KP (2016) Total Knee and Hip Reconstruction in Male Patient with Alkaptonuria with 3 Years of follow up: Case Report and Review of the Literature. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol 4(3): 00137. DOI: 10.15406/mojor.2016.04.00137

Alkaptonuria is a rare disorder of tyrosine metabolism, characterized by the excretion of homogentisic acid with urine, which causes darkening when exposed to air and the deposition in certain tissues, especially in joint cartilage. Ochronosis or ochronotic arthropathy, first described by Virchow in 1866,1 demonstrates a rare expression of alcaptonuria. In our study we report a case of a 62-year old man who was subjected to a total knee arthroplasty, during which was detected extensive osteoarthritis and brown to black pigmentation of the joint surfaces, the femoral condyles, the tibial Plateau, the menisci and the quadriceps tendon. The same findings were encountered in the subsequent total hip and knee arthroplasties, performed after 3 and 6 months respectively. Alcaptonuria was diagnosed according to the laboratory and pathological tests. We report this case as there are very few clinical references in the literature and it is extremely rare for a patient to have undergone three total arthroplasties with preoperatively undiagnosed alcaptonuria.

Keywords: Alkaptonuria, Ochronosis, Ochronotic arthritis, Homogentisic acid

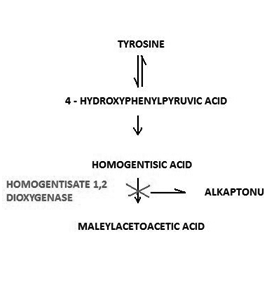

Alcaptonuria is an extremely rare metabolic disease and is defined as an autosomal recessive inherited deficiency of the hepatic enzyme oxidase of the homogentisic acid1,2 (Figure 1). Deficiency of the enzyme causes accumulation of the homogentisic acid in the cells and the body fluids. The disease is characterized by the following three specific conditions, excretion of homogentisic acid in the urine, arthritis and ochronosis. Homogentisic acid accumulates and is polymerized into a blue-black pigment that is ultimately deposited in the skin, cartilage and collagenous tissues. Specifically, pigment deposition can be seen in skin, bones, articular cartilages, ear and sclera, heart endocardium and valves, and kidneys (the so called ochronosis).3 The accumulation eventually causes severe degeneration of the spine and peripheral joints, like knees, hips and shoulders.

Figure 1 The catabolic path of tyrosine. Deficiency of the hepatic enzyme oxidase of the homogentisic acid causes alcaptonuria due to the accumulation of homogentisic acid.

What is of scientific interest is the fact that an Egyptian mummy of 1500 BC was diagnosed with the disease.4 In the USA it is encountered with a frequency of 1/1,000,000. Moreover, it is reported in high frequency in Slovakia5 and the Dominical Republic.6 It affects all races and both males and females with equal frequency. However, the course of the disease is found to be more severe in males.7 Bibliography demonstrates no relevant references about the frequency of alcaptonuria in Greece. Diagnosis is based on the darkening of urine with exposure to air. Additionally, by the reduction of iron chloride they obtain a blue-green color and they even become brown by the addition of Benedict reagent. Urine chromatography, which demonstrates the most specific method, is in most cases not necessary.

In our case a male, 62 years old at the time of the first surgery, was admitted for evaluation in our department due to persistent pain in the right hip and knees. No significant information arose from the history as the patient did not suffer from any chronic disease, did not take medication on a regular basis, did not smoke and had no family history of arthritis. What may be of great magnitude is his occupation, which was associated with liquid fuels in a station of petrol refilling for forty years. We found it impossible to take genetic material for genetic testing in any number of his family and, thus, our attempt to diagnose the external ochronotic arthropathy was impossible with the means at our disposal.

Bibliography refers only two cases of external ochronosis so far, concerning only the skin, while no prior case of ochronotic arthropathy has been recorded.8 Clinical examination of the patient revealed severe pain during flexion and extension of the knee, with indications of intra-articular collection of small volume of liquid, with full flexion and without extension deficit. He complained of pain during the internal and external rotation of the right hip. The radiological outcome demonstrated image of osteoarthritis in the right knee with reduction of the medial compartment and ostephytic changes and formations on the patella. Additionally, there were present extensive alterations in the left knee to a greater extent, at least radiologically, although its clinical condition was milder (Figure 2). We also detected severe osteoarthritis in the right hip (Figure 3).

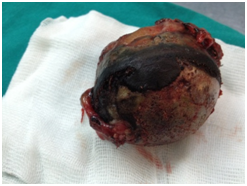

The patient was scheduled for surgery of total right knee arthroplasty. During the surgical approach of the knee we observed the dark pigmentation of the synovium, the bone cartilage, the quadriceps tendon and the menisci. This rare condition, characterized by many as ‘’Black Bone Disease’’, is accompanied by extensive destruction of the femoral condyles and the tibial Plateau due to arthritis. We performed a cemented total arthroplasty and sent pieces of the bones and the meniscus for histological examination (Figure 4).

Histological examination confirmed the clinical diagnosis. The disease is ochronotic arthropathy or alcaptonuria. The confirmation was enhanced by urine examination as well as by examination of pieces of the synovium, the meniscus and bone pieces of the knee (Figure 5) and synovial liquid (Figure 6). At the overview of the patient we detected dark pigmentation of sclera, which is characteristic of alcaptonuria (Figure 7).

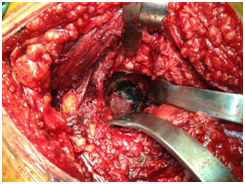

After the postoperative recovery of the patient, we scheduled the total arthroplasty in the right hip, which was performed 3 months after the previous operation on the knee, with great success in both cases (Figures 8 & 9). Six months later, the total left knee arthroplasty was performed, being also successful (Figure 10). It is extremely rare for a patient suffering from alkaptonuria to be subjected to three total arthroplasties with the syndrome not being preoperatively diagnosed. From this fact, emerges the great clinical significance of this case.

Figure 9 Total hip arthroplasty. The characteristic dark pigmentation of the femoral head and the acetabulum.

Figure 10 Total arthroplasty of left knee. The characteristic brownish color of the cartilaginous surfaces.

Follow up During the follow – up examination of the patient three years after the first total knee arthroplasty , two and a half year after the total hip arthroplasty and two years after the second total knee arthroplasty , the clinical and radiographic outcome was excellent. The patient walks normally and without the help of crutches, performs complete flexion and extension of the knees and complete movements of the right hip not accompanied by pain during the flexion, internal and external rotation. Comparison of the length of the two extremities showed no difference, the patient did not mention any pain in daily life activities (Figure 11).

The ochronotic arthropathy is a common expression of alcaptonuria, an extremely rare metabolic disease, defined as an autosomal recessive inherited deficiency of the hepatic enzyme ‘oxidase of the homogentistic acid’. Patients with alcaptonuria are usually free of symptoms in childhood and adolescence,9-11 however the hyper pigmentation of the urine can be observed even in childhood.12 A percentage of 25% do not present dark hue of the urine and, thus, many patients with ochronosis remain undiagnosed until adulthood. The insufficiency of sucrose - isomaltase13 as well as the neonatal hyperparathyroidism can be inherited together with alcaptonuria. Ochronosis can be exogenous, induced by several harmful substances such as phenol, trinifenoli, benzene and hydroquinone. In exogenous ochronosis the arthropathy observed in alcaptonuria is absent.

Ochronotic arthropathy appears usually during the third or fourth decade of life and is more severe in males. It has been suggested that clinical manifestations of alkaptonuric ochronosis are usually delayed, not appearing until the fourth decade of life because with ageing the renal clearance of homogentisic acid decreases.14 Mild and extremely rare, extensive ochronotic arthropathy has been reported in children. The most frequent manifestations of the disease are diffuse calcification of the intervertebral disk followed by narrowing of the intervertebral space and specific type of arthropathy of the axial skeleton and the peripheral joints. Peripheral arthritis is observed in almost all patients, as they grow in age.15,16 It first appears in knees, hips, shoulders, seldom in small joints of hands, and it is manifested by pain, limited morbidity and hydrarthrosis. Bibliography mentions appearance of intervertebral disc herniation17 as well as spontaneous tendon rupture both as first manifestations of the disease.18

Apart from the musculoskeletal system, alcaptonuria affects other systems, such as cardiovascular, by secondary calcification of the aortic valve,19 being probably so severe that requires urgent replacement of the aortic valve,20 aortic stenosis21-23 and ischemic heart disease, leading to myocardial infarction. Nevertheless, there are references mentioning attack of the urinary system with the presence of swelling and calculus of the prostate, nephrolithiasis, renal failure, usually in late stages,24,25 as well as attack of the respiratory system with the appearance of throat dryness, dysphagia and dyspnea.

Until now, no specific therapy has been found.26 The recommended therapy is the reduction of the intake of phenylalanine and tyrosine and the increase of the intake of ascorbic acid, without strong clinical evidence. The destruction of the cartilaginous joint surfaces is extensive and appears at a young age, so that the patient requires a total arthroplasty before the age of 60. The total arthroplasty constitutes the unique solution to improve the quality of life for those patients.

Total joint replacement in published cases of ochronotic osteoarthritis report good results similar to osteoarthritic patients without ochronosis. Because all these are reports, no guideline is available for replacement of the knee or hip joints in ochronotic patients27 (Table 1). In our review of the world literature we found very few studies upon the subject of early loosening of the arthroplasty in patients with ochronotic arthropathy. Spencer et al.28 reported that they met no complication following arthroplasty on 11 joints of 3 patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis attributable to ochronosis. They reported no implant deficiency including total hip arthroplasty or any problem in 12 years follow up period.28 As in the whole spectrum of the metabolic bone diseases, the potential of early failure of the arthroplasty is increased.29,30 In our research in the literature, we found no reports mentioning cases of revision of knee and hip arthroplasty.

|

Article |

Year |

Age/Gender |

Joint |

Prosthesis Type |

Follow Up |

Results |

|

Konttinen et al.31 |

1989 |

58 / M |

Bilateral Knees |

Cement less |

--- |

Good |

|

Carrier and Harris32 |

1990 |

70/m |

Bilateral Knees and Hips |

---- |

--- |

Improvement |

|

Ramsperger et al.33 |

1994 |

57/M |

Left Knee |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Aydogdou et al.34 |

2000 |

48/M |

Left Knee |

Cement less |

4 Years |

Good |

|

Demir35 |

2003 |

70/M |

Bilateral Knees |

Cemented |

14 Months |

Good |

|

Moslovac et al.36 |

2003 |

70/M |

Bilateral Knees and Hip |

Cemented |

7 Years |

Excellent |

|

Fisher and Davis37 |

2004 |

69/M |

Bilateral Knees and Hip |

--- |

5 Years |

Improvement |

|

Spencer et al.38 |

2004 |

53/F |

Knee |

--- |

7 Years |

Good |

|

Kotela et al.39 |

2008 |

59/M |

Bilateral Knees |

Cemented |

--- |

Good |

|

Kefeli et al.40 |

2008 |

60/F |

Bilateral Knees |

Cemented |

10 Months |

Good |

|

Araki et al.41 |

2009 |

56/M |

Bilateral Knees |

Cement less |

--- |

Good |

|

Babak Siavashi et al.42 |

2009 |

54/F |

Right Hip |

Cemented |

--- |

--- |

|

Fontao - Fernandez et al.43 |

2010 |

68/F |

Left Knee |

--- |

--- |

Good |

|

Abimbola et al.44 |

2011 |

48/M |

Left Knee |

Cemented |

2 Years |

Excellent |

|

Varvitsiotis et al.45 |

2014 |

53/M |

Bilateral Shoulder |

--- |

6 Years |

Good |

|

A.Malakasi et al.46 |

2012 |

77/M |

Right Knee |

Cemented |

--- |

Good |

|

Mehmet Ali Acar et al.47 |

2013 |

62/F |

Right Hip and Left Knee |

Cemented hip and cement less knee |

18 Months |

Good |

|

Ramadan et al.48 |

2013 |

69/M |

Bilateral Knees |

Cemented |

1 year |

Excellent |

Table 1 Published literature

In our case, the patient mentions dramatic improvement of the quality of life after the three operations in the knees and hip. As there are no particular contraindications and cases of early loosening of the arthroplasty in those patients, the total arthroplasty constitutes the only invasive therapy. The experience we obtained from our arthroplasty practices on the three joints of our case, confirms it.

None.

None.

©2016 Adamopoulos, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.