MOJ

eISSN: 2374-6939

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 3

1Neurosurgery Department, University Hospital, Argentina

2Spine Surgery Unit, Hospital Espanol, Argentina

Correspondence: Alfredo Guiroy, Spine surgeon, Adolfo Calle 2839, Guaymallen, Mendoza, Argentina, Tel 543000000000

Received: November 04, 2016 | Published: November 4, 2016

Citation: Guiroy A, Ciancio AM, Molina FF, Jalón P, Gagliardi M, et al. (2016) Microendoscopic Decompression (MED) of the Lumbar Spine Initial Experience Including 30 Cases. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol 6(3): 00220. DOI: 10.15406/mojor.2016.06.00220

Objective: to describe and assess 30 cases of microendoscopic decompression (MED) of the lumbar spine.

Introduction: degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis is one of the most common surgical conditions of the spine in the elderly. This condition affects quality of life and impairs function. Surgery leads to a better outcome than non surgical treatment. This condition occurs mostly in elderly patients, so it is vital to reduce operative time, hospital length of stay and the probability of complications. Minimally invasive techniques differ from “open” procedures on a reduced stress on healthy tissues, and so this translates into less postoperative pain, a shorter hospital stay and a low complication rate.

Material and methods: we performed a retrospective analysis of 30 patients undergoing surgery. Twelve patients presented claudication, 13 had unilateral sciatic involvement, and the rest of the patients presented a combination of symptoms. Instability was rule out with dinamics X-rays. The Visual Analog Scale of pain (VAS) was compared at the pre and postsurgical period. Claudication was assessed according to patient´s answer: resolved, better, the same. One level MED was performed with a 18 mm diameter tube on every case.

Results: pre and post surgical VAS had an average predictive value of 66.27% (p < 0.01). Claudication improved in three cases, and resolved completely in the rest of the cases. No worsening was seen. Mean hospital stay was 22.6 hours (12-48h) with a mean time of 24 hours. Mean post-surgery follow up was 22.36 months (18-26).

Conclusion: in our series of 30 patients undergoing minimally invasive endoscopic lumbar decompression good pain management, improved claudication, a shorter hospital stay and a lower complication rate were observed.

Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis is one of the most common conditions of the spine in the elderly. The etiology is multifactorial, and includes facet and ligament hypertrophy, degenerative disc disease and dynamic narrowing due to instability. These factors lead to a reduced lumbar canal diameter, decreased lateral recesses and intervertebral foramina causing compression of the neural structures.

Clinically, this translates into pain, which may be either lumbar or radiated pain, claudication which improves with flexion, positive sagittal balance as a pain -control mechanism, nerve disorders in the lower limbs, and, in advanced cases, neurological deficit. This condition affects quality of life and impairs function.

As reported in the literature, surgery leads to a better outcome than non surgical treatment.1,2 Since this condition occurs mostly in elderly patients, it is vital to reduce operative time, hospital length of stay and the probability of complications. Minimally invasive techniques differ from “open” procedures in that the approach is made through a small incision in the skin with sequential muscle splitting using tubular retractors, without de-inserting the midline fascia. Stress on healthy tissues is reduced, and so this translates into less postoperative pain, a shorter hospital stay and a low complication rate.3-6

Material and methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of 30 patients undergoing surgery (Table 1).

|

Case |

Gender |

Age |

VAS pre |

VAS post |

VAS Change |

Neurogenic Claudication |

Hospital Stay |

Leg pain |

Level |

Follow Up |

|

I |

M |

73 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L4-5 |

26 |

|

2 |

F |

69 |

8 |

4 |

4 |

Yes |

24 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

23 |

|

3 |

F |

83 |

8 |

2 |

6 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L4-5 |

20 |

|

4 |

F |

61 |

9 |

3 |

6 |

Yes |

24 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

26 |

|

5 |

F |

80 |

10 |

3 |

7 |

Yes |

48 |

No |

L4-5 |

18 |

|

6 |

M |

73 |

10 |

3 |

7 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L5-S1 |

19 |

|

7 |

M |

62 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

No |

18 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

21 |

|

8 |

F |

73 |

8 |

2 |

6 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L4-5 |

23 |

|

9 |

M |

79 |

7 |

5 |

2 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L3-4 |

23 |

|

10 |

F |

59 |

5 |

1 |

4 |

No |

18 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

26 |

|

11 |

F |

47 |

8 |

3 |

5 |

No |

18 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

20 |

|

12 |

F |

70 |

9 |

2 |

7 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L4-5 |

21 |

|

13 |

M |

67 |

10 |

2 |

8 |

Yes |

24 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

25 |

|

14 |

F |

54 |

8 |

3 |

5 |

No |

12 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

24 |

|

15 |

M |

61 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

No |

24 |

Yes |

L3-4 |

25 |

|

16 |

M |

78 |

9 |

2 |

7 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L5-S1 |

18 |

|

17 |

F |

83 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

Yes |

48 |

No |

L3-4 |

21 |

|

18 |

M |

67 |

9 |

2 |

7 |

No |

24 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

26 |

|

19 |

F |

59 |

9 |

3 |

6 |

No |

12 |

Yes |

L3-4 |

19 |

|

20 |

M |

74 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L4-5 |

21 |

|

21 |

M |

69 |

9 |

4 |

5 |

No |

24 |

Yes |

L5-S1 |

22 |

|

22 |

F |

75 |

8 |

2 |

6 |

Yes |

24 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

23 |

|

23 |

M |

68 |

10 |

2 |

8 |

Yes |

18 |

No |

L4-5 |

21 |

|

24 |

M |

58 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

No |

12 |

Yes |

L3-4 |

23 |

|

25 |

F |

47 |

8 |

2 |

6 |

No |

12 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

25 |

|

26 |

F |

61 |

9 |

5 |

4 |

No |

18 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

20 |

|

27 |

F |

64 |

8 |

3 |

5 |

No |

24 |

No |

L5-S1 |

23 |

|

28 |

M |

54 |

10 |

5 |

5 |

No |

24 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

26 |

|

29 |

F |

51 |

7 |

2 |

5 |

No |

12 |

Yes |

L4-5 |

21 |

|

30 |

F |

84 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

Yes |

24 |

No |

L3-4 |

22 |

Table 1 Demographics of patients undergoing surgery

The clinical presentation was compatible with lumbar spinal stenosis in all the patients included. Twelve patients presented evident claudication, 13 had unilateral sciatic involvement, and the rest of the patients presented a combination of symptoms (Table 2). Lumbalgia was not the main symptom in any of the cases.

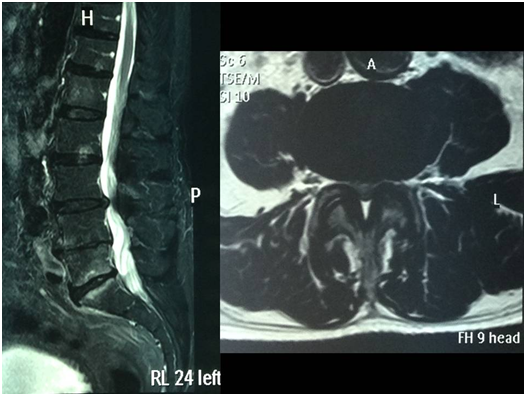

All the patients were assessed with dynamic lumbar X-rays and MRI of the lumbo-sacral spine. Patients with more than Grade II spondylolisthesis (Meyerding grading scale), mobile listhesis as shown in dynamic X-rays, spondylolysis, multisegmental narrow canals, facet synovial cysts and patients with a history of lumbar spine surgery were excluded. Thirteen male and seventeen female patients underwent surgery. Mean age was 66.7 yrs. (47-84); median age, 73. Levels L4-L5 (20), L3-L4 (6) y L5-S1 (4) were surgically managed (Figure 1).

Figure 1 case 1: 78 yrs old male presenting claudication at 50 meters. The MRI shows narrowing in the L3-L4 segment. MED was performed and the clinical symptoms resolved.

The Visual Analog Scale of pain (VAS) was compared at the pre and postsurgical period using the t test for matched samples and the Wilcoxon test; a p< 0.0001 was obtained. Info Stat/E software was used for statistic estimations (Table 3). Claudication was assessed according to patient´s answer (3 options): resolved, better, the same.

|

Age (Range) |

66.76 (47-84) |

|

Men |

13 (43.3 %) |

|

Hospital stay (SD) |

22.6 ( +/- 8.29) |

|

Level |

|

|

L3-L4 |

6(20%) |

|

L4-L5 |

20(66.66%) |

|

L5-S1 |

4(13.33%) |

|

leurogenic claudication |

16 (53.33%) |

|

Leg pain |

17 (56.66%) |

|

Follow up (large) |

22.36 (18-26) |

Table 2 Demographics Summary

|

VAS Pre |

VAS Post |

Change |

P value |

|

|

Media(SD) |

||||

|

Visual analogic scale |

8.3 (1.36) |

2.8 (1.12) |

5.5 (1.35) |

<0.0001 |

Table 3 Comparative Study with VAS of pain (Visual Analog Scale)

We used ventral position under general anesthesia. Decubitus sites were padded. A fluoroscopy-guided unilateral paramedian approach with sequential dilation using tubular retractors was used; an 18mm diameter working channel with an articulated arm was used attached to a 30 grades optic endoscopy device (METRx, Medtronic- Sofamor Danek®). Access was always from the side the patient described as more symptomatic; in the cases of intermittent claudication a left side access was chosen for surgical comfort. An electrocautery device was used to clean perifacet and supralaminar soft tissue.

Laminotomy of the lower third of the superior lamina and the upper third of the inferior lamina was performed with a drill and a Kerrison rongeur. An osteotomy of the medial third of the homolateral facts was performed. Before removing the ligamentum flavum the endoscope was angulated to aim at the contralateral side to perform the decompression, including the lower segment of the spinous process. Finally, the flavectomy and fluoroscopy-guided check of the release were done. For closure, the fascia, subcutaneous cell tissue and the skin were grasped with stitches.

The pre and post surgical Visual Analog Scale (VAS) had an average predictive value of 66.27% (p < 0.01) (Table 3 and Figure 2). Claudication improved in three cases, and resolved completely in the rest of the cases. No worsening was seen. Mean hospital stay was 22.6 hours (12-48h) with a mean time of 24 hours. Mean post-surgery follow up was 22.36 months (24-32). As for complications, one patient developed deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and was given anticoagulation therapy without any clinical impact.

Thanks to the use of modern imaging techniques it is known today that most of the compressions occur in the interlaminar space, and so the older decompression techniques, such as laminectomy, have been replaced by focal laminotomy involving also the lateral recess and medial osteotomies of the joint facets. Such laminotomies are also useful to spare the integrity of the midline structures, with the possibility of post-surgical muscle reinsertion. In 1988 Young et al.7 described a hemi-laminectomy with a unilateral approach and bilateral decompression under the midline structures.

Later, several authors reported good results with this technique, which underscores the usefulness of the unilateral approach for bilateral decompression. In 2002 Khoo et al.6 described 25 patients with lumbar stenosis undergoing micro-endoscopic decompression (MED), and then compared the results with a control group including 25 patients treated with the open technique. The authors reported a lower intraoperative bleeding rate, a shorter hospital stay and less use of narcotics in the post-operative period with the same outcome in terms of pain management and claudication as compared to the open approach.

Minimally invasive decompression may be performed using different image intensification methods. Neurosurgeons are familiar with the use of the surgical microscope, which is a good option for this type of procedures. The remarkable contribution of the endoscope as compared to the surgical microscope is that the light of the optic fiber comes from the tip of the working channel, so the instruments may be used without generating any shadows or blind spots. Therefore, very small working channels may be used (16 and 18 mm of diameter), which would be difficult with the surgical microscope for the light is not able to advance through the tube. Also, a 30° angle optic may be used, which is very useful when decompressing the contralateral side (Figures 3,4).

Bone and ligament decompression is similar to that obtained with the conventional open technique, with less muscle de-insertion. Many authors state that this is the key for better results in terms of postoperative pain, and less paraspinal muscle atrophy.8,9

On the other hand, the use of the endoscope requires a learning curve, more technical equipment and specific instruments.

In our series of 30 patients undergoing minimally invasive endoscopic lumbar decompression good pain management, improved claudication, a shorter hospital stay and a lower complication rate were observed.

None.

None.

©2016 Guiroy, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.