MOJ

eISSN: 2374-6939

Case Report Volume 15 Issue 1

Rheumatology Unit, Hospital Provincial del Centenario, National University of Rosario, Argentina

Correspondence: Ariana Ringer, Rheumatology Unit, Hospital Provincial del Centenario, National University of Rosario, Argentina

Received: January 01, 2023 | Published: January 18, 2023

Citation: Lucci F, Ringer A, Ruffino JP, et al. Lupus Hepatitis, a diagnostic challenge. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol. 2023;15(1):6-8. DOI: 10.15406/mojor.2023.15.00609

Subclinical liver disease is common in systemic lupus erythematosus, between 25% and 50% of patients with lupus may develop abnormal liver function at some point, evidenced by an increment on transaminases. Although it is still a controversial issue, there is evidence in the literature that systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) itself is not associated with specific, severe and progressive liver injury. Several authors have pointed out the role of SLE in triggering a liver disease that is often subclinical, called “lupus hepatitis”, concomitant with exacerbations of the disease that returns to normal after treatment with glucocorticoids.

In many cases liver involvement is due to hepatotoxic drugs, viral hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or primary liver diseases such as concurrent autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) as an independent disease, primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Distinguishing whether the patient has primary liver disease with associated autoimmune clinical and laboratory features resembling SLE (such as AIH) or whether the increment of liver enzymes is a manifestation of SLE, remains a challenge for the treating physician. We present a clinical case of a patient with a recent diagnosis of SLE who presented acute cholestatic liver disease associated with relapse of the underlying disease.

A 25-year-old woman with a recent diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus and grade II lupus nephritis presented with a 14-day evolution condition characterized by severe, colicky type, abdominal pain with a predominance on upper hemiabdomen, without irradiation, with partial response to non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, associated with nausea and two episodes of self-limiting diarrhea (hypocholia). She also referred polyarthralgia predominantly in the hands, wrists, shoulders, and knees, disabling for daily activities, associated with weight loss of 10 kilos, photosensitivity and alopecia. Physical examination revealed normotension, heart rate 90 bpm, afebrile, no lymph nodes, alopecia, malar rash, no presence of mucosal ulcers or synovitis; generalized mucosal cutaneous jaundice. The abdomen was soft, depressible and painless, with positive air-fluid sounds without visceromegaly.

Laboratory: glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) 426UI/L, glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT) 159UI/L, alkaline phosphatase 1582UI/L, gamma-glutamil transaminase (GGT) 727UI/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 330, Total bilirubin 7.79 mg/dL (direct bilirubin 6.02/indirect 1.77), prothrombin time (PT) 10.1 sec and Kaolin partial thromboplastin time (KPTT) 37.2sec. Immunological laboratory: Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) 1/5120, extractable nuclear antigen antibodies (ENA) Panel:71 IU, dsDNA reactive, SmD1 reactive, C3 28 mg%, C4 11 mg%, positive antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin antibodies (ACL) IgM, IgG and B2 glycoprotein 1. A thorough immunological panel was requested to rule out non-reactive PBC and AIH (antimitochondrial antibodies -AMA- M2, Sp 100, anti-smooth muscle antibodies and liver/kidney microsomal antibodies -LKM1, Gp210, LC1, SLA-). Serology for hepatotropic viruses were negative (Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Hepatitis A, B and C viruses).

Cholangial-MRI, arterial and vein echo-doppler and abdominal tomography were requested with no hierarchical findings, such as thrombosis.

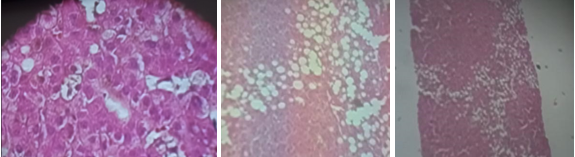

Liver biopsy: scant lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate without exceeding the plaque limit, cholestatic liver disease with signs of ductopenia and hepatic steatosis with discrete non-expansive, pericellular portal fibrosis. Liver parenchyma with preserved histoarchitecture and 12 evaluable portal spaces. Slight fibrous expansion, absence of lobar ducts, images of ductular proliferation and remains of bile ducts surrounded by scant lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. These alterations were observed in all the portal spaces presented in the sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Liver biopsy.

Footnote: scant lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate without exceeding the plaque limit, cholestatic liver disease with signs of ductopenia and hepatic steatosis with discrete non-expansive, pericellular portal fibrosis.

Treatment with 500 mg of methylprednisolone in pulses for 3 days, hydroxychloroquine 400 mg per day and ursodexosicolic acid 900 mg per day were indicated. Improvement in symptomatology and a decrease in liver enzymes were observed lately in the course of the disease.

Liver abnormalities can be found in patients with SLE and they are mostly transient. Chronic, progressive and severe disease due to SLE itself is infrequent.1 Many causes of liver compromise have been described, such as drug-induced toxicity, viral hepatitis, fatty liver disease and autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly and transaminase increase, followed by ascites and jaundice are some of the most frequent signs.2–5 The patterns of liver enzymes can suggest hepatocellular damage, cholestasis and mixed causes, guiding the diagnosis.6,7

Neither SLE classification guidelines nor disease activity tools describe liver dysfunction, presumably due to the benign and transitory abnormalities that can be found in most of the cases. Nevertheless, there are many stablished manifestations including primary forms related to SLE, like autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), also known as lupoid hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). On the other hand, secondary forms such as drug-induced liver injury (DILI), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and vascular disorders can also be elucidated.8,9

Lupus hepatitis is commonly associated with SLE flare, usually asymptomatic or related to mild symptoms. The laboratory can show hypertransaminasemia, bilirubin increment and some other features like anti-ribosomal P antibody positivity.10 In the histopathology it can be observed mild portal infiltration with lymphocytes, neutrophils and plasma cells, hydropic degeneration, steatosis, mild cholestasis, focal necrosis and nodular cirrhosis.11 It is an exclusion diagnosis that forces to rule out other primary causes and secondary hepatic disorders.8,9

AIH is a challenging differential diagnosis, requiring liver biopsy in most cases. This entity presents some typical features in the histopathology, evidencing lobular or periportal infiltrates, interface hepatitis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, portal mononuclear infiltrates that invade the limiting plate causing fragmentary periportal necrosis periportal and rosettes formation. If the disease progress, bridging necrosis, panlobular or multilobular necrosis and finally cirrhosis can be observed. Bile ducts may also be affected, causing ductopenia, destructive and non-destructive cholangitis.12 Along with lupus hepatitis, they can both present with arthralgias, hypergammaglobulinemia and aminotransferases increment, but AIH reveal positive ANA, anti-smooth muscle antibodies and liver/kidney microsomal antibodies.13,14

Others relevant differential diagnosis are PBC and PSC. In both pathologies cholestasis is the main sign. Jaundice and pruritis are also common findings. Antimitochondrial antibodies are found in PBC and anti-LKM antibodies in PSC. Biopsy will help with the diagnosis. In the former, a chronic and progressive destruction of intrahepatic ducts is observed, while in the latter, intra and extrahepatic ducts are affected with inflammation and scarring, that leads to obstruction. Overlap syndromes have also been detailed in patients with SLE.15,16

Many drugs used in rheumatology can cause DILI. The drugs that most frequently produce this side effect are non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen is the safest), azathioprine and methotrexate. Cyclophosphamide and leflunomide have a moderate risk, while those rarely associated with DILI are hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and steroids.17,18

Regarding viral infections, they have a close relationship with autoimmunity. While, viral diseases may trigger autoimmune diseases, immunosuppressive treatment in SLE may predispose to a higher predisposition to get infections Frequent viruses that can cause hepatic damage are Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Herpes Simplex virus, and Varicella zoster virus. Hepatitis B and C viruses are the two most common hepatotropic viruses that lead to chronic viral hepatitis .19

Other causes that are associated with liver disorders are given by states of hypercoagulability and liver vascular disorders.

Finally, patients with SLE may have vascular diseases of the liver as they may be susceptible to develop thrombosis as it happens in anti-phospholipid syndrome. Portal thrombosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome (obstruction of the suprahepatic veins or inferior vena cava) and hepatic artery thrombosis are some examples. SLE is associated with a higher prevalence of positive antiphospholipid antibodies, causing or not thrombotic disease. They are usually related to SLE activity. In the presented case, the patient had active SLE with hepatitis and positive ACL antibodies, without thrombosis.19,20

Altered liver function is very common in patients with SLE, but lupus hepatitis itself as a manifestation of the underlying disease is considered rare, and can sometimes evolve into a more aggressive form, presenting itself as a diagnostic challenge for the treating physician. It generally responds to treatment with glucocorticoids, which, in the case presented, did not manifest early, after having performed pulses with methylprednisolone. For this reason, liver biopsy was a fundamental tool for establishing the diagnosis, ruling out secondary causes, and establishing the appropriate treatment.

None.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

©2023 Lucci, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.