MOJ

eISSN: 2374-6939

Case Report Volume 12 Issue 6

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, J. N. Medical College, A.M.U, India

Correspondence: Yasir Salam Siddiqui, Assistant professor, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, J. N. Medical College, A.M.U, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India, Tel +919837343400

Received: September 30, 2020 | Published: December 31, 2020

Citation: Sharique M, Siddiqui YS, Abbas M, et al. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva - a case report with brief literature review. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol. 2020;12(6):132-135. DOI: 10.15406/mojor.2020.12.00536

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) is an exceptionally uncommon autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterized by defects in skeletogenesis manifesting as congenital malformations of the great toes and progressive postnatal induction of disabling ectopic endochondral osteogenesis. During early course of disease patients of FOP are often misdiagnosed as having soft tissue sarcoma or aggressive juvenile fibromatosis and hence sometimes undergo invasive procedures that usually lead to the speeding up of disease process. Therefore early correct diagnosis of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva is necessary to prevent additional iatrogenic insult. The case study is being presented to highlight the clinical features of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, difficult aspect of diagnosis and management with brief literature review.

Keywords: fibrodysplasia ossificans, iatrogenic insult, heterotopic ossification

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) is an exceptionally uncommon autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterized by defects in skeletogenesis that manifest as congenital malformations of the great toes (hallux valgus, malformed first metatarsal, and/or monophalangism) and by progressive postnatal induction of disabling ectopic endochondral osteogenesis.1–4 Involvement of dorsal, axial, cranial, and proximal anatomic locations precede involvement of ventral, appendicular, caudal, and distal areas of the body. The FOP has prevalence of approximately one in 2 million individuals.1,5,6 Children with FOP appear normal at birth except for congenital malformations of the great toes. In the first decade, disease is characterized by development of inflammatory fibro-proliferative masses in the axial skeleton. Neck stiffness is an early finding in most patients and can precede the onset of heterotopic ossification.1,3,4,7 Lesions are characterized by the prompt advent of painful, highly vascular fibro-proliferative masses that advance through an endochondral ossification to form mature bone.4,8 Though lesions may develop spontaneously, while falls, injuries, intramuscular injections, viral ailments, and surgical stress can precipitate new flare-ups resulting in heterotopic ossification.

During early course of disease patients of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva are often misdiagnosed as having soft tissue sarcoma or aggressive juvenile fibromatosis and hence sometimes undergo invasive procedures (biopsy) that usually lead to the speeding up of disease process.9 Therefore early correct diagnosis of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva is necessary to prevent additional iatrogenic insult.6,9 As the disease advances patients become increasingly disabled due to ankylosis of the major joints of axial and appendicular skeleton and are frequently confined to a wheelchair by the age of 30 years.4,9,10 Currently there is no definitive treatment for the disease. A short-term course of high dose steroids, started within the first 24 hours of a flare-up, may help to diminish the intense inflammation and tissue edema seen in the early stages of the disease. Anticipatory management is based on prevention against falls, respiratory deterioration and viral illness. The median life expectancy is nearly 40 years of age. Maximum patients are wheelchair bound by the completion of the second decade of life span and commonly perish of complications of thoracic inefficiency.11 The case study is being presented to highlight the clinical features of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, difficult aspect of diagnosis and management with brief literature review. The patients and their parents were informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication, and they consented.

A 3½ years old male child presented to us with complaints of development of multiple painful swellings over the occiput, nape of neck, both scapular areas, both axillas, thoracolumbar spine for last 3 months. The swellings were increasing in size gradually and were followed by progressive limitation of movements of neck and shoulders. The antenatal and early post natal history was unremarkable, except for hallux valgus deformity of both feet, noted immediately by parents after birth (Figure 1). There was no history suggestive of any developmental delay in child. To begin with, parents noticed a small swelling over the nape of neck, which was followed by development of multiple swellings on scapular regions, axillas, occiput, and thoracolumbar area (Figure 2). There was no history of injury, fever, hearing loss, battered baby syndrome. Prior to visit of the patient to our medical college, patient’s parents had consulted for bilateral great toe deformity to an orthopaedic surgeon before the onset of multiple swellings. At that time the attending doctor reassured the parents and had not suspected of the possibility of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). This fact highlights the difficult aspect of diagnosis of the disease even with presence of bilateral hallux valgus deformity, a qualified orthopaedic surgeon fails to detect the disease before the appearance of multiple swellings. Hence, there are difficulties in diagnosing FOP, and delayed diagnosis or even misdiagnosis is common.

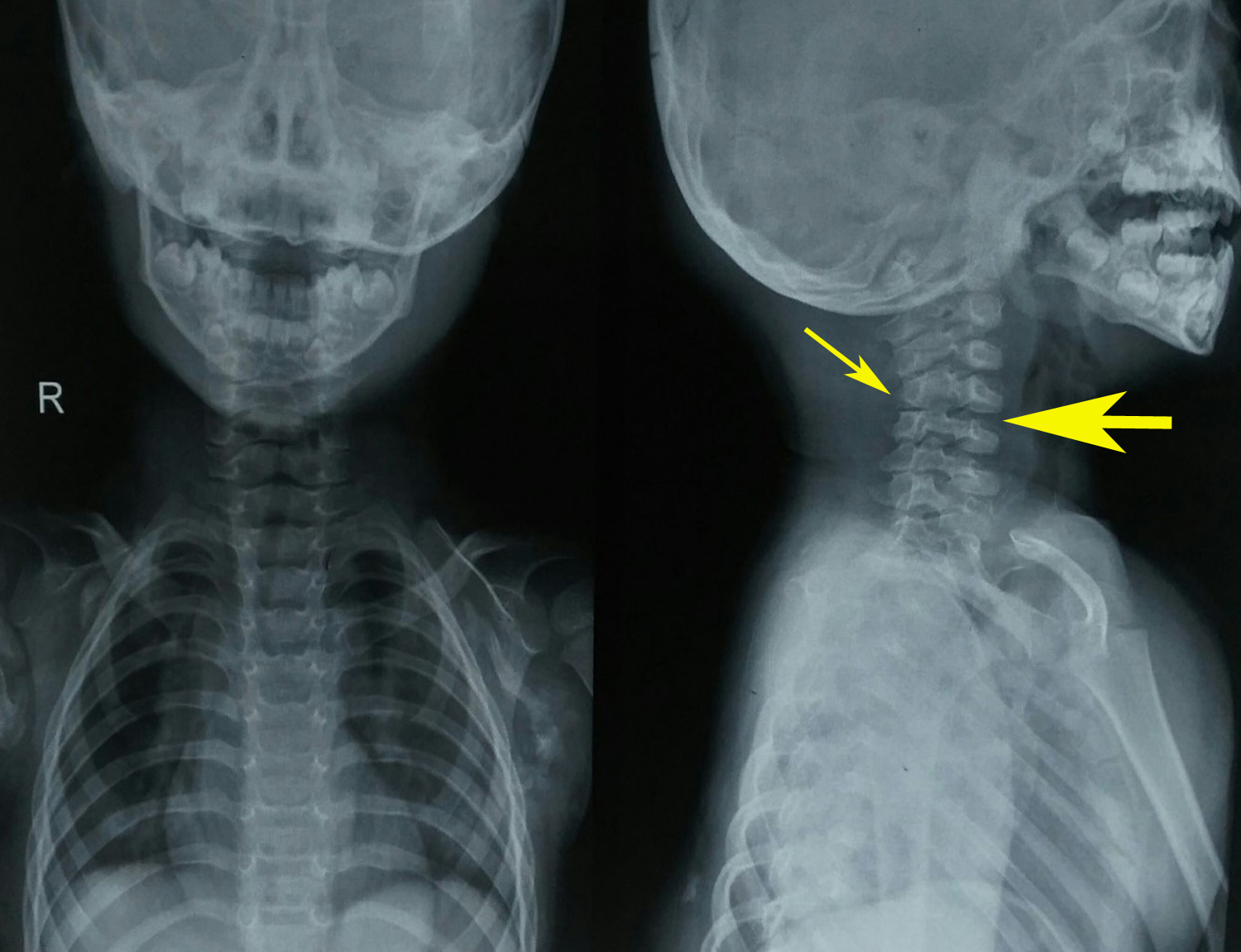

Physical examination revealed bilateral shortening and valgus deformity of the great toes (Figure 1). Multiple swellings of variable size were present on occiput, nape of neck, bilateral scapular area, bilateral axilla and midback. Swellings were non tender, hard, smooth, mobile with well-defined edges and were lying in subcutaneous tissues & muscles. Movements of the neck and bilateral shoulder were decreased (Figure 3). Rest of the joints including bilateral hips, elbows, wrists, knee, and ankle were normal. A radiograph of the right shoulder showed osteomas between the scapula and the proximal end of the humerus (Figure 4). Cervical spine radiographs revealed large posterior elements, narrow vertebral bodies and loss of cervical lordosis (Figure 5). Radiograph of the dorso-lumbar spine revealed large ectopic bone mass bridging the lower dorsal and lumbar spine (Figure 6). Radiograph of the knees revealed the presence of osteochondromas of the proximal medial end of the tibia (Figure 7). Lab findings were normal except for raised ESR (50mm in first hour) & liver enzymes were mildly raised. Patient was diagnosed as a case of FOP on the basis of clinico-radiological examinations. Biopsy was not done because of the fear of flaring up of the disease. Oral prednisolone was given in a dose of 2mg/kg for 5 days. Acute flare of the disease settled and the patient was discharged with advice of regular follow-ups.

Figure 2 Multiple bony mobile swellings on occiput, nape of neck, bilateral scapulae, posterior axillary folds & thoracolumbar area.

Figure 3 Decreased range of motion of shoulders (right > left). Any passive attempt on moving shoulders, was painful as evidence by facial expression of patient.

Figure 4 A radiograph of the right shoulder showed variable sized osteomas (arrow) with calcifications between the scapula and the proximal end of the humerus.

Figure 5 Cervical spine radiograph revealed large posterior elements (thin arrow), narrow vertebral bodies and loss of cervical lordosis (thick arrow).

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva is a severely incapacitating genetic connective tissue ailment characterized by congenital malformations of the great toes and proceeding heterotopic ossification at extraskeletal sites.1 Various synonyms for the disease are fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva or myositis ossificans progressiva or stone man syndrome. FOP is an uncommon condition with a global prevalence of approximately 1 case in 2 million individuals. No ethnic, racial, or terrestrial predisposition has been defined.1,5,6 FOP is a severely incapacitating heritable connective tissue disorder characterized by congenital malformations of the great toes and progressive heterotopic ossification that forms qualitatively normal bone in typical extraskeletal sites.1 Involvement of dorsal, axial, cranial, and proximal anatomic locations precede involvement of ventral, appendicular, caudal, and distal areas of the body. Congenital malformation of great toes is in the form of hallux valgus, malformed first metatarsal (as was observed in our patient), and/or monophalangism.1,12 FOP is the most disabling condition of ectopic skeletogenesis. Children with the disease are born normal except for congenital disfigurements of the great toes (Figure 1). Classically, the first decade of existence, is haunted by occurrences of painful soft tissue masses over the body3 and are frequently mistaken for tumors4 (Figure 2). There are difficulties in diagnosing FOP, hence delayed diagnosis (as in our case) or even misdiagnosis is common. One study mentioned that nearly 90% of patients with FOP worldwide are misdiagnosed and 67% undergo dangerous and unnecessary diagnostic procedures.9,13

While some flare-ups spontaneously regress, flare-ups can transform soft tissues (skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, and aponeuroses) into heterotopic bone. Newly formed bone (Figure 4 & 6) spans the joints, renders movement impossible.5,14 The natural history of this condition is characterized by inflammatory episodes of 2 to 3 weeks, with latency periods of several months in between. Ectopic skeletogenesis follows a specific anatomic configuration, involving the dorsal, axial, cranial, and proximal regions of the body first, followed by involvement of ventral, appendicular, caudal and distal regions later.1,6 The most common site for the onset of heterotopic ossification is the neck, with the spine and shoulder girdle being the next most common sites.1,4,6 Though heterotopic ossification in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva begins in childhood; but trauma such as minor soft tissue injury, muscular stretching, overexertion and fatigue, intramuscular injections and influenza-like illnesses can persuade flare-ups of the disorder. Loss of movements is accumulative and most patients are wheelchair bound by the end of the second decade. However, diaphragm, tongue, cardiac muscles, smooth muscles and extra-ocular muscles are spared from abnormal ossification.

In addition to progressive loss of movements, other life threatening complications include severe weight loss following ankylosis of the jaw, as well as pneumonia and right-sided heart failure resulting from ectopic thoracic skeletogenesis.1,15 Limb swelling, hearing loss may also be seen due to involvement of lymphatics and ear.1 FOP involves possible dysregulation of the bone morphogenetic protein signaling pathway.2,16 Literature also supports that association of the inflammatory component of the immune system in FOP.10 The occurrence of inflammatory cells in the lesions, flare-ups following viral infections, the sporadic timing of flare-ups, and the favorable response of corticosteroids, supports involvement of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of FOP.16

Plain radiographs show ectopic ossifications of soft tissues. Cervical spine radiographs reveals large posterior elements, tall narrow vertebral bodies, and fusion of the facet joints with frank bony ankyloses.1,17 Advanced disease shows bony bridges across the spine and joints rendering movements impossible as was seen in our patient. Other abnormalities features are short malformed thumbs, clinodactyly, short broad femoral necks, and proximal medial tibial osteochondromas.18 ACT scan can be useful to better analyze ossifications; MRI and technetium bone scan can show lesions at an initial stage, when they are not yet ossified. Laboratory investigations generally do not reveal any significant abnormality.

The diagnosis of FOP is clinic-radiological and does not require biopsy. Clinical doubt of FOP early in life on the basis of hallux valgus & short first metatarsal can lead to preliminary diagnosis and thus can prevent harmful effects of invasive diagnostic procedures. Biopsy can result in a new ectopic ossification. So biopsy should be avoided. Routine biochemical assessments do not contribute to the diagnosis of FOP. Plain X-rays can substantiate more subtle great toe abnormalities and the presence of heterotopic ossification. Sophisticated imaging studies is generally unnecessary from a diagnostic standpoint. FOP must be distinguished from other genetic conditions of heterotopic ossification and soft tissue sarcomas. Till present, there is no treatment for FOP.1,2 Corticosteroids and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs are largely used to control the acute symptoms (flare up of disease) during the inflammatory phases, but their effectiveness is uncertain. Efforts to excise heterotopic bone for diagnostic purpose or for improving joint movement can lead to episodes of explosive new bone formation. Frederick S Kaplan12 concluded that fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva is not only an extremely disabling disease but also a condition of substantially shortened lifespan. The median lifespan is approximately 40 years of age.12,19 Most patients are wheelchair-bound by the end of the second decade of life. The most common cause of death in patients with FOP is cardiorespiratory failure from thoracic insufficiency.

Our case study portraits the typical features of FOP, both clinically and radiologically. Moreover the diagnosis is missed at initial contact of patient, because of exceptionally rare occurrence of disease and unawareness of the doctors towards the disease. Even though sporadic and exceptionally rare, one should contemplate FOP as one of the differential diagnosis in patient with multiple swellings in association with progressive loss of joint movement. The treatment is symptomatic with prevention of trauma,(including iatrogenic) to avoid disease exacerbations.

None.

None.

©2020 Sharique, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.