MOJ

eISSN: 2381-179X

Case Report Volume 8 Issue 2

1Department of Microbiology, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College & General Hospital, India

2Department of Pediatrics, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College & General Hospital, India

Correspondence: Arghadip Samaddar, Department of Microbiology, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College & General Hospital, India, Tel +919932560720

Received: March 21, 2018 | Published: March 21, 2018

Citation: Samaddar A, Tendolkar U, Tripathi D, et al. Pulmonary and meningeal infection with Cryptococcus neoformans serotype D in an HIV infected child. MOJ Clin Med Case Rep. 2018;8(2):52 – 55. DOI: 10.15406/mojcr.2018.08.00239

Cryptococcosis generally presents with meningitis. Though lungs are the portal of infection, pulmonary infection is less commonly encountered. Pulmonary cryptococcosis may present as pleural effusion, interstitial opacities, consolidation, reticulonodular cavities and rarely acute respiratory failure. The present case was a 10-year-old boy, from India who was admitted with fever, fronto-parietal headache and body ache for 1 month. He was HIV-infected (parents were also HIV-infected) and was receiving ART. He presented with small subcutaneous nodules over the face, productive cough with expectoration and breathlessness for 15 days. His CD4 count was markedly reduced. The CSF and sputum grew yeast identified as Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans Serotype D, thus confirming active pulmonary cryptococcosis with discharge of cryptococci in sputum, a very rare finding and cryptococcal meningitis with cutaneous dissemination. The patient was treated with amphotericin B, fluconazole and 5-flucytosine. This case represents pulmonary cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus neoformans. Serotype D which is rarely seen in Indian population. Moreover, the young age of the patient and demonstration of capsulated yeast in sputum were unusual findings. This case highlights the importance of routine negative staining of respiratory specimens in symptomatic patients to detect the yeasts which may help timely institution of therapy and probably prevent dissemination.

Keywords: cryptococcosis, cryptococcus neoformans, nigrosin, pulmonary cryptococcosis, pediatric cyrptococcosis

Meningoencephalitis is the commonest presentation of cryptococcosis. However, pulmonary cryptococcosis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infected individuals is under diagnosed and without appropriate treatment, leads to severe disseminated disease. Three recognised varieties of the genus Cryptococcus are Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii(Serotype A), Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans(Serotype D) and Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii(Serotype B & C). The majority of cases are caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, whereas Cryptococcus gattii accounts for a smaller proportion of cases, often in immunocompetent patients. There are practically no prospectively obtained data regarding the management of pulmonary cryptococcosis in either the immunocompromised or immunocompetent patients. Diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis is challenging as it mimics pulmonary tuberculosis and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia. Histopatholgy is most commonly employed for diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis but cryptococci have rarely been demonstrated in sputum.

A 10-year-old male, hailing from Ratnagiri district of Maharashtra, India was admitted to the hospital, with history of fever accompanied by fronto-parietal headache and body ache for 1 month. He also complained of productive cough with expectoration and breathlessness for 15 days. The patient was diagnosed with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection 1 month before admission, following which he was started on anti-retroviral therapy (ART). His mother was diagnosed with HIV infection 3 years ago and was started on ART. His father was also diagnosed with the same 2 months back, but was not on treatment. The patient had a 13 year old sibling who was HIV seronegative. Local examination revealed gross emaciation, small subcutaneous nodules about 3-5 mm in diameter over face (Figure 1) and palpable post auricular & bilateral medial axillary lymph nodes. Neurological examination did not reveal any meningeal signs apart from brisk plantar reflexes. Haematological parameters showed macrocytic anaemia with anisocytosis on peripheral blood smear, gross leucopenia (1900 cells/mm3) and mildly elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR 35mm at 1 hour). Serum creatinine was high (1.2 mg/dl). He had hypokalemia and severe Vitamin B12 deficiency. CD4 count was markedly reduced (8 cells/mm3). Chest X-Ray revealed diffuse infiltration in the right middle and lower lobes (Figure 2). Ultrasonography (USG) of abdomen revealed multiple, non-necrotic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Computed tomography (CT) scan of brain showed age unrelated atrophy (Figure 3).

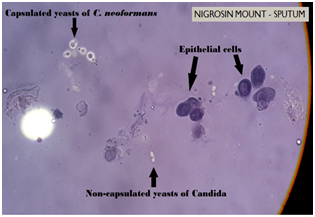

CSF obtained by Lumbar puncture, expectorated sputum and clean catch mid-stream urine sample were received in the Department of Microbiology. Routine bacteriological examinations of Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) and urine were unremarkable. Wet mount preparation of CSF revealed occasional lymphocytes and budding capsulated yeast cells in negative staining with 10% Nigrosin. Gram stain of CSF showed occasional pus cells and Gram-positive budding yeast cells. Wet mount of sputum revealed budding yeasts with epithelial cells and pus cells. 10% Potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount of sputum showed budding yeast cells and Nigrosin preparation revealed non-capsulated yeast cells suggestive of Candida as well as capsulated yeast cells suggestive of Cryptococcus sp. (Figure 4). Gram stain of sputum revealed polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), epithelial cells and Gram-positive budding yeast cells. Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain and culture both were negative for acid fast bacilli. On Gomori’s Methanamine Silver (GMS) stain Pneumocystis jiroveci was not seen.

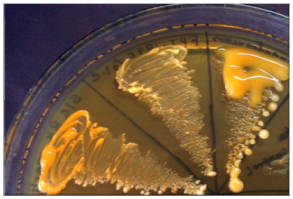

Fungal culture on Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar (SDA) revealed yeast-like, mucoid, cream coloured colonies appeared after 48 hours of incubation. The growth was identified as Cryptococcus neoformans on the basis of growth at 37°C, hydrolysis of Christensen’s urea agar, assimilation pattern of inositol and nitrate and browning of growth on Bird Seed Agar (BSA) (Figure 5). Serotype identification was done by inoculating the colony on creatinine-dextrose-bromothymol blue-thymine (CDBT) medium to check for thymine assimilation. Yellow to orange colonies were produced on this medium thereby identifying the isolate as Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans (Serotype D) (Figure 6). The other three serotypes Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii (Serotype A) and Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii (Serotypes B & C) do not assimilate thymine and hence do not produce orange colonies on this medium. Black colonies of C. neoformans were picked up from sputum inoculated on BSA and identified as same serotype. Histopathological examination of skin biopsy also revealed capsulated yeasts.

Based on mycological investigations, it was confirmed as a case of pulmonary cryptococcosis with cryptococcal meningitis and cutaneous dissemination. The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B 1 mg/kg per day for 15 days, followed by IV amphotericin B with oral fluconazole for 15 days, followed by 5-flucytosine for 19 days. Tablet azithromycin 250 mg was given orally thrice daily. ART with zidovudine and efavirenz was instituted initially. Due to persistent anaemia, therapy was switched over to tenofovir, lamivudine and ritonavir boosted lopinavir after three and half months. CD4 count after 3 months was 13cells/mm3. Patient was discharged on oral fluconazole 150 mg orally, once daily, after 42 days of hospital stay. However, the Patient was readmitted after a week with complaints of headache and vomiting with no respiratory symptoms. The repeat sample of CSF did not show growth of Cryptococcus neoformans. The subcutaneous nodules had resolved (Figure 7). The patient was discharged after 8 days.

Cryptococcosis is a re-emerging global mycosis affecting both immunocompetent and immunocompromised host. It typically occurs in immunocompromised patients such as those with HIV/AIDS. In an epidemiological study of 1491 patients diagnosed with cryptococcosis between 1992 and 2000, a total of 58 (4%) presented with pulmonary disease and only 12 (0.8%) were not human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected.1 Furthermore, among immunocompetent subjects, Nadrous et al.,2 reported that 36 (86%) of 42 with cryptococcal infection had isolated pulmonary involvement. It is estimated that approximately 1,000,000 cases of cryptococcal infection occur annually in HIV-infected patients.3,4 Cryptococcosis is rarely encountered in children. In the United States, 6.2 cases of cryptococcosis per 1 million hospitalizations in childrens’ hospital have been documented.5 Median age is 8 years among paediatric patients (range 2-17 years). Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans and Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii cause infection generally in immunocompromised individuals, whereas Cryptococcus gattii is responsible for disease in immunocompetent hosts.6 Severe meningoencephalitis is the commonest presentation; however, pulmonary cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive individuals is underdiagnosed and without appropriate treatment leads to severe disseminated disease.7 Approximately one-third of the patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis are asymptomatic.8 Of the remainder, one-half have cough or chest pain, 32% have sputum production that is bloody 18% of the time. Weight loss and fever occur in approximately 26%.9 The most common radiographic findings in the immunocompetent host are single or multiple peripheral nodules, interstitial opacities, consolidation, reticulonodular cavities, pleural effusion and rarely acute respiratory failure.9

In our case, meningeal symptoms had preceded respiratory symptoms, though the natural history of the disease suggests a primary respiratory route followed by dissemination. Radiological presentations in pulmonary cryptococcosis are varied and nonspecific including nodules, consolidation, cavitary lesions, and a diffuse interstitial pattern, influenced by the underlying immune status of the patient. In our case, diffuse infiltration was noted in the right middle and lower lobes on chest X-Ray. Diagnosis is based on isolation of Cryptococcus from, or detection of cryptococcal antigen in a pulmonary specimen, coupled with appropriate clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings. Among eight paediatric cryptococcosis cases reported between 2005 and 2015 (4 cases from India and 4 from other countries).5,10-13 Cryptococcus sp. was never isolated from sputum. Cryptococcus neoformans is rarely seen in sputum and culture may occasionally be positive. In adults, pulmonary cryptococcosis has been reported mostly in immunocompromised patients. Even among these, documentation of Cryptococcus sp. in sputum is lacking. Most of these cases have been diagnosed on histopathology or only in culture. Direct microscopy for sputum was positive in only 2 cases but there is no photographic documentation in these reports.14,15 Treatment recommendations include induction therapy with an amphotericin B preparation and flucytosine for immunocompromised patients and those with severe disease and fluconazole for mild-to-moderate, localized disease.16 In our case, induction therapy was initiated with IV amphotericin B and flucytosine, followed by fluconazole as consolidation and maintenance therapy.

This case is of clinical and mycological interest as it highlights the occurrence of paediatric pulmonary cryptococcosis, demonstration of capsulated yeast cells in sputum and isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans Serotype D in culture. In India, Cryptococcus neoformans Serotype A is most common, followed by Serotype B. Serotype D causes less severe disease and is common in European countries.14 Since natural history suggests pulmonary lesions to occur prior to dissemination, routine nigrosin observation of respiratory specimens in symptomatic patients should detect the yeasts. Such an observation may help timely institution of therapy and probably prevent dissemination.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Samaddar, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.