MOJ

eISSN: 2381-179X

Case Report Volume 9 Issue 3

Metropolitan General Hospital, Mesogeion Avenue 264, Greece

Correspondence: Stavros I Daliakopoulos, Metropolitan General Hospital, Mesogeion Avenue 264, 15562 Cholargos, Greece

Received: May 12, 2019 | Published: June 18, 2019

Citation: Daliakopoulos SI, Stergianni M, Karagkiouzis G, et al. Primary malignant Germ-Cell tumors of the anterior mediastinum in adults. Report of two rare cases and review of the literature. MOJ Clin Med Case Rep. 2019;9(3):68-74. DOI: 10.15406/mojcr.2019.09.00307

Introduction: Malignant germ-cell tumors are usually located in the gonads. Extragonadal germ-cell tumors are extremely rare and are typically located in midline structures and, especially, the anterior mediastinum. They are divided into seminomas and non-seminomatous germ cell tumors. The former is a radiosensitive tumor that can be successfully treated by surgery and radiation. The latter is a very rare category including: yolk sac tumor (YST), embryonal carcinoma (EC), choriocarcinoma (CC) and combined germs cell tumors (CGCTs). These tumors with relatively unknown clinical behavior are uncommon neoplasm of the mediastinum and only sporadic cases have been documented in the literature.

Case presentation: We report two male patients referred to our team with huge bulky tumors of the anterior mediastinum, infiltrating into adjacent anatomical structures for consultation and management. At the time of admission one of the patients presented with grossly edematous upper extremities and engorged cervical veins suggesting Superior Vena Cava (SVC) syndrome. The patients were treated surgically at first instance, for different medical reasons each, the unusual neoplasms with the different biologic behavior were totally excised or not, according to each case surgical demands and the systemic manifestations of the neoplasms were reversed.

Conclusion: Malignant germ cell tumors are suspected among anterior mediastinal tumors affecting male patients of around 20 years old. Tumor markers must be investigated and tissue histology should be diagnosed for specimens obtained by mediastinoscopy or anterior mediastinotomy. In case of Non-Seminomatous Germ Cell Tumors (NSGCT) or a-Fetoprotein and/or humane Chorion gonadotropin producing seminoma, the first choice remains chemotherapy. Means for surgical decision making are based only on dramatically worsening clinical indicators of SCV syndrome because initial debulking surgery is rarely useful.

Keywords: anterior mediastinum, yolk sac tumor, primary malignant germ-cell tumors

YST, Yolk sac tumor; EC, Embryonal carcinoma; CC, Choriocarcinoma; CGCTs, Combined germs cell tumors; SVC, Superior Vena Cava; NSGCT, Non-Seminomatous Germ Cell Tumors; AFP, α-fetoprotein; β-HCG, beta human chorionic gonadotropin; BEP regimen, bleomycin etoposide cisplatin; TIP, paclitaxel ifosfamide cisplatin

The purpose of this article is to affirm the literature and show that Kim’s SLE was caused by combined factors of genetic and environmental agents. Kim already had a genetic predisposition for SLE. Yet, although her immune system was susceptible to SLE, Kim’s exposure to environmental factors in the Bronx, New York, could have triggered genetic changes within her gene and chromosomes. After two years of being admitted to our Rehab Center, Kim had a double hip replacement, a stool transplant due to frequent and chronic C-diff infection; she also mourned her stepmother’s death due to Lupus. Kim’s condition raised two questions: How did she get Lupus? And what is the phenotype and genotype of this disease? Recently, Kim suffered a relapse related to her diagnosis of Lupus. After spending two weeks post admission, she was discharged from the hospital. She complained that she didn’t receive physical therapy during her recent hospital experience and she felt overwhelmed with feelings of general weakness, especially to her lower extremities.

The posterior mediastinum presents a tendency to develop metastatic tumours especially gonadic ones, because of the lymphatic drainage of the testes and the thoracic aorta in the posterior mediastinal, whereas anterior mediastinal space characterized by tumour growth of primary aetiology.1 The regions of the rare presence of primary seminoma is the pineal body, the mediastinum and the retroperitoneum. The mediastinal region is the most common site of seminoma. The latter is in the anterior mediastinum, involves predominantly young males and corresponds to 25-30% of malignant mediastinal germ cell tumours.2–6 The thymus gland is often the primary hosts of mediastinal seminoma.7,8 Even if there are supporters of thymic genetic origin of the primary seminoma, the latest theory professes ectopic seminoma of a tumour originating in the gonads.9

Additionally, yolk salk tumour is a germ cell tumour which behave as a mixed tumour within other tumours of the same category as teratoma (35%), or as an extremely rare pure solitary one like in our case.10,11 Two interesting rare cases presented in this report which concern two categories of germ cell tumours: mediastinal seminoma and pure yolk sac tumour.

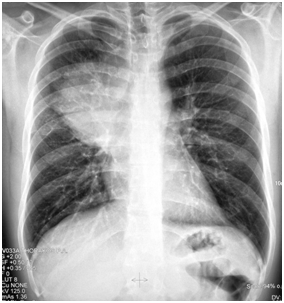

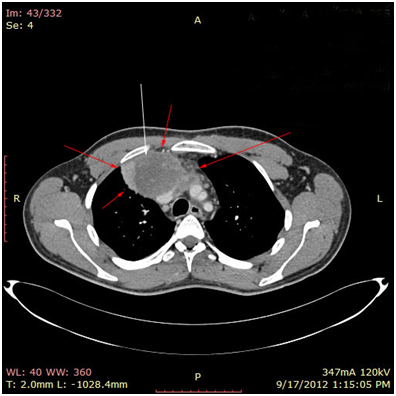

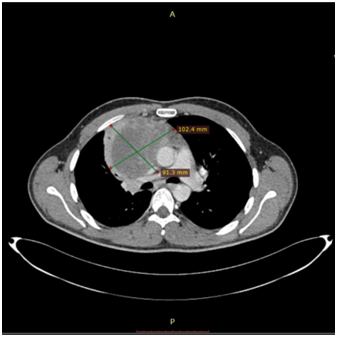

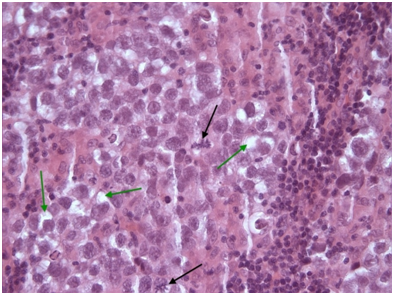

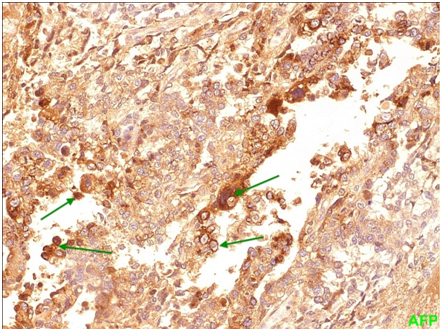

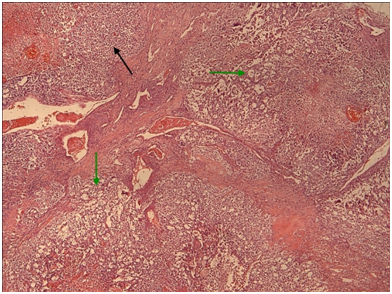

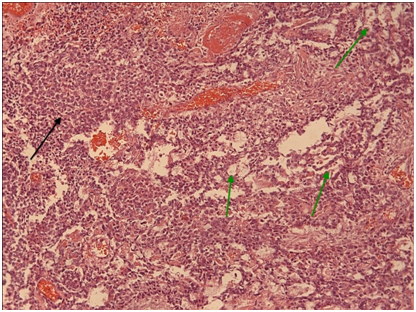

The 1st case we report is of a 22-year-old Caucasian male, who was admitted to our hospital with a 3-days history of progressive dyspnea on exertion, neck swelling, fatigue, persistent chest pain, pyrexia, and a cough that was occasionally productive of blood. The physical examination revealed a heart rate of 115 beats per minute (Sinus Rhythm), a respiratory rate of 25 breaths per minute and superficial vascular distention over the neck. Laboratory studies revealed elevated serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) (5380 IU/ml) and D-dimer (481ng/ml). A chest X-ray in the poster - anterior view, upon admission, depicted a suggestive right upper mediastinal mass (Bild 1). Radiography was followed by contrast-enhanced CT scan that revealed a large, homogeneous mediastinal mass crossing into the anterior mediastinum and compressing – encasing the superior vena cava. It also showed signs of thrombosis of the left brachiocephalic vein, and multiple filling defects at the left pulmonary artery indicating embolism. Subcarinal lymphadenopathy, as well as enlarged lymph nodes of the right hilum was present (Bild’s 2-5). On median sternotomy, a large non resectable tumor was observed involving the in nominate vein and the superior vena cava (Bild 6). Great care was taken to remove as much tumor mass as possible. To decompress the superior vena cava, we had to perform an extensive resection and reconstruction of the cephalad part of the superior vena cava using homolog pericardium.A histopathological examination of a section of the mass revealed a mixed NSGCT (embryonal yolk sac/endodermal sinus tumour), containing also elements of embryonal carcinoma (Figure 1-6).The patient was placed on cisplatin-based chemotherapy (BEP regimen: cisplatin 50mg/m2 on days 1-2, etoposide 165mg/m2 on days 1-3, bleomycin 30U on days 1, 8, and 15, every 3 weeks). Tumor markers were elevated for a-FP (214ng/mL) and normal for β-HCG. The patient completed 4 cycles of chemotherapy and the subsequent chest CT (Bild 7) revealed a partial remission of the mass (decrease>50% of the size). The a-FP was normal as well as the β-HCG. The remaining mass was inoperable so the patient was started on salvage chemotherapy with the TIP (paclitaxel, ifosfamide, ciplatin) regimen for 4 cycles. The post-chemo chest CT showed stable disease and the patient was referred to radiation oncologists for radiotherapy of the remaining tumor. Three months later af P was found elevated and the CTs revealed multiple brain metastases. Whole brain radiation was performed and the patient was placed on gemcitabine (d1 and d8 every 21 days). Two months later the neurologic status deteriorated with new brain metastases and the patient passed away (19 months after the diagnosis).

Bild 1 Yolk sac tumor. The initial chest radiograph demonstrating soft tissue fullness along the right hilum and mediastinum that obscures the hilar anatomy.

Bild 2 CT – axial plan of a large Yolk sac tumor in the anterior mediastinum invading the art. Carotis communis. White arrow pointing low attenuation foci, suggesting central necrosis.

Bild 4 CT – axial plan demonstrating a 10cm Yolk sac tumor invading the truncus pulmonalis and the vena cava superior.

The 2nd case we report is of a 42-year-old Caucasian male who sought the gastroenterology outpatient clinic complaining of dysphagia for about 4 months. Laboratory findings were normal. X-ray with a contrast material (barium X-ray) and upper GI endoscopy were performed and the patient was treated for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease via lifestyle changes and oral medication with proton-pump inhibitors. Two months later the symptom had precipitated and after oesophageal pH monitoring was performed, surgical treatment was decided. Before the surgery, an MRI scan of the chest showed a large mass of the anterior and middle mediastinum (Bild’s 8-9). PET showed marked uptake only in the mediastinal mass. Fine needle aspirates and core biopsies yielded a poorly differentiated neoplasm. Blood tests for germ cell tumor markers showed a normal a-fetoprotein level and an elevated β-HCG level (31mIU/ml). Thoracoscopy was performed to obtain sufficient tissue and histopathological examination of a section of the neoplasia revealed a seminoma (Figure 7-12). Testicular sonography was performed to look for an occult primary tumor. The testicles were normally positioned and symmetric in size and echogenicity. No mass was present. Thoracotomy revealed a dark, solid mass adherent to the pericardium, which was removed. Patient was placed on cisplatin-based chemotherapy (BEP regimen: cisplatin 50mg/m2 on days 1-2, etoposide 165mg/m2 on days 1-3, bleomycin 30U on days 1, 8, and 15, every 3 weeks). Patient completed 4 cycles of chemotherapy without major hematologic toxicity. A subsequent chest CT revealed a decrease in the size of the middle mediastinum remaining mass (from 5,5x2,5 to 2,3x1,5cm). The fluorine-18, deoxy-2-fluoro-d-glucose positron emission tomography (PET)–computerized tomography (CT) (PET–CT) was negative for viable disease. The remaining mass was inoperable so the patient was offered follow up with 3monthly chest CT and tumour markers (b-HCG, aFP, LDH) for the first year, 4monthly for the second year and twice a year for years 4,5 and 6. Today, 76 months after the diagnosis the patient is in perfect health without any signs of relapse.

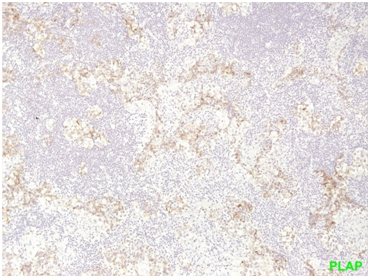

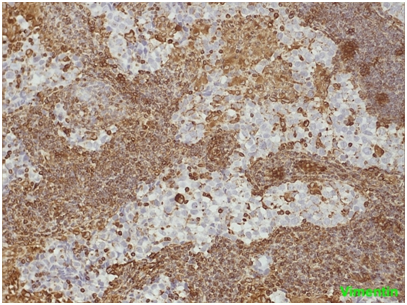

Figure 1 seminoma PLAP positivity (membranous straining pattern) in a significant number of tumor cells.

Figure 2 seminoma the neoplastic cells show no positivity for Vimentin. On the contrary, the lymphocytes of the fibrous septa are indisputably positive.

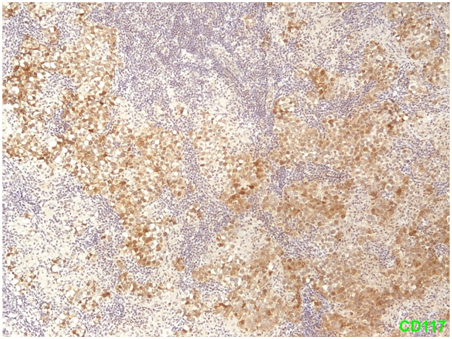

Figure 3 Seminoma Positivity of tumor cells for CD117/c-kit (membranous & cytoplasmic staining pattern).

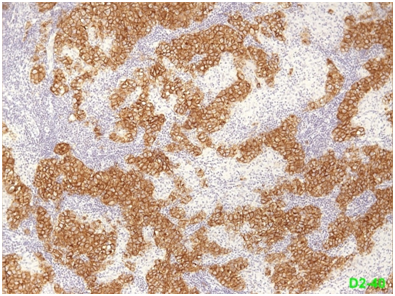

Figure 4 Seminoma the neoplastic cells are also positive (membranous staining pattern) for D2-40 (podoplanin).

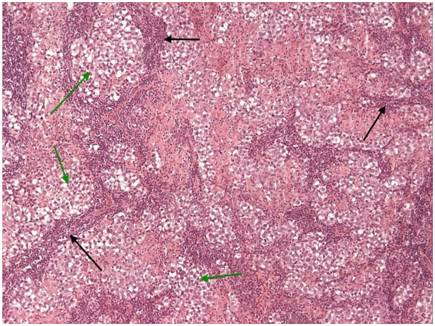

Figure 5 Mediastinal seminoma, like its gonadal counterpart, shows islands (green arrows) of large tumor cells with optically clear cytoplasm (due to large amounts of stored glycogen). These islands are separated by fibrous septa (black arrows) heavily infiltrated by non-neoplastic lymphocytes. (H + Ex10).

Figure 6 Seminoma tumor cells of seminoma with clear cytoplasm (green arrows). Two prominent atypical mitotic figures (black arrows) H+Ex40.

Figure 7 Yolk sac Membranous and cytoplasmic positivity for AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) is seen in a significant number of neoplastic cells.

Figure 9 Yolk sac the microcystic / macrocystic reticular pattern of growth (green arrows) is the most common finding in yolk sac tumors (>70% of cases).Nevertheless, it is possible to encounter more solid areas (black arrow). (H+E,x4).

Figure 10 Yolk sac therefore mentioned growth patterns with Schiller-Duvall type focal papillary structures in greater magnification. (H+E,x10).

Seminomas are slow growing, bulky tumors that invade locally early in the growth process. Patients may present with symptoms of compression of surrounding structures, like dyspnea, dysphagia cough and chest pain or even constitutional symptoms like fever and weight loss. Mediastinal adenopathy and superior vena cava syndrome (SVC) syndrome may uncommonly occur. About 20-30% of patients are asymptomatic. The most common clinical features that may suggest this rare entity are summarized in Table 1.

Tumor Type |

Proportion % (range) |

Suggestive Clinical Features |

Non-small-cell lung cancer |

50 (43-59) |

History of smoking; often age > 50 yr |

Small-cell lung cancer |

22 (7-39) |

History of smoking; often age > 50 yr |

Lymphoma |

12 (1-25) |

Adenopathy outside the chest; often age < 65 yr |

Metastatic cancer |

9 (1-15) |

History of malignant condition |

Germ-cell cancer |

3 (0-6) |

Usually, male sex and age <40 yr; elevated levels of β human chorionic gonadotropin or alpha- fetoprotein are common |

Thymoma |

2 (0-4) |

Characteristic radiographic appearance on the basis of the location of the thymus; frequently associated with the parathymic syndromes (e.g., myasthenia gravis and pure red-cell aplasia) |

Mesothelioma |

1 (0-1) |

History of asbestos exposure |

Other cancers |

1 (0-2) |

Table 1 Malignant Causes of the Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Management of the superior vena cava syndrome associated with malignant conditions involves both treatment of the cancer and relief of the symptoms of obstruction. Most data regarding management of the superior vena cava syndrome are from case series; randomized trials are scarce. The median life expectancy among patients with obstruction of the superior vena cava is approximately 6 months; but estimates vary widely according to the underlying malignant conditions. Surgical bypass grafting is infrequently used to treat the superior vena cava syndrome. The rates of illness after resection and reconstruction range between 80 to 90% with an underlying mortality of approximately 5%. Rates of occlusion of the superior vena cava of 10% have been reported after surgical reconstruction.12–19

Management is guided by the severity of the symptoms and the underlying malignant conditions as well as by the anticipated response to treatment. For example, in patients with lymphoma, small-cell lung cancer, or germ-cell tumors, the clinical response to systemic chemotherapy alone typically is rapid. 12-16,20-24

Mediastinal non-seminomatous germ cell tumors are more frequent in individuals with Klinefelter syndrome and are associated with a risk of subsequent development of hematologic neoplasia that is not treatment related.25,26 Approximately 50% of patients with mediastinal non-seminomatous germ cell tumors will survive with appropriate management.27

Yolk sac tumor is a primitive malignant germ cell tumor. Some of the histological patterns of yolk sac tumor recapitulate the various phases in the development of normal yolk sac. The usual age group affected is children and young adults.

Extra gonadal non-seminomatous germ cell tumors are highly sensitive to cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens.28 In fact, during the last three decades, the clinical outcome of NSGCT has been dramatically improved since the introduction of cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Pure seminoma is sensitive to radiotherapy and the prognosis is good.29 However, the prognosis for the NSGCT is poor,30 5-year overall survival rate of mediastinal NSGCT is much lower than that of gonadal NSGCT.25,26,27

Primary mediastinal malignant GCT is often prone to be misdiagnosed, because of their nonspecific clinical symptoms. Although the success of chemotherapy regiments in Primary mediastinal malignant GCT is important, skilled thoracic surgery even aggressive resection is an equally important component for successful multidimensional therapy.31

The superior vena cava syndrome is often clinically striking. Most of cases are due to malignant conditions. Treatment planning should be multidisciplinary. Relevant data on the tumor type and stage of the cancer should be used to guide the therapy (i.e., chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both or, in occasional cases, surgery alone or in combination with other therapies); these types of therapy can relieve the symptoms of obstruction of the superior vena cava in the vast majority of patients. High risk is partially related to tumor bulk, to chemotherapy resistance, and to a predisposition to develop hematologic neoplasia and other non germ cell malignancies.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest

©2019 Daliakopoulos, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.