MOJ

eISSN: 2381-179X

Case Report Volume 11 Issue 2

1Intensive Care Unit, Guizhou provincial people’s Hospital, China

2NHC Key Laboratory of Pulmonary Immune related Disease, Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital, China

Correspondence: Jianquan Li, Intensive Care Unit, Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital, China, Tel 0086-0851-5625209, Fax 0086-0851-5625209

Received: February 10, 2021 | Published: March 8, 2021

Citation: Long D, Wang Y, Wang J, et al. Fatal sepsis caused by mixed bloodstream infection of klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola in community: a case report in China. MOJ Clin Med Case Rep. 2021;11(2):24-29. DOI: 10.15406/mojcr.2021.11.00375

Objective: We report a patient died within 72 hours after community-acquired bloodstream infection caused by klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola in China.

Measurements: A 52-years male was admitted to hospital due to unknown high fever, cough and headache. He had the medical history of diabetes and Gout. Patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly after symptom onset. Anti-viral, anti-positive coccal treatments combined with the anti-fungal therapy were administered before examination results were released. The laboratory examinations including the blood routine, culture of blood sample, chest CT and abdominal ultrasonography were tested. Additionally, the PMseq-DNA Pro High throughput gene detection was used to screen the source related to fungi, bacteria, mycobacteria, mycoplasma/chlamydia, parasites and viruses.

Main results: All examinations excluded the viruses, fungi, mycoplasma/chlamydia infection and parasitic infection. Treatments including anti-fungi, anti-virus and antibacterial drug across a broad-spectrum failed to improve patient’s symptoms. Patient’s condition worsened and rapidly entered sepsis and subsequent sepsis shock, with death occurring 72 hours after symptom onset. The classic bacterial culture only revealed the klebsiella pneumonia infection, and klebsiella is sensitive to antibiotics used for this patient. While PMseq-DNA Pro high throughput gene detection of the blood sample was acquired one day after the patient died, which showed the mixed infection of klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola.

Conclusion: It is a very rare case reported previously that patient died from bacterial infection within short period of time. Klebsiella variicola could contribute to illness rapid progression in this case. Classic method is limited in guiding the anti-infection therapy for complex cases, early genetic detection should be recommended in the diagnosis and management of complex infection.

Keywords community-acquired bloodstream infection, mixed infection, klebsiella variicola, klebsiella pneumoniae, high throughput gene detection

The klebsiella causing infection is a well-known type of infection with its high incidence and mortality. It causes outbreaks of nosocomial infections and even drug resistance, and can lead to infection in the community among health-care patients or people with underlying immunodeficiency.1 Based on genetic analysis, the klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) contains three polygroups: klebsiella pneumoniae (KpI), K.quasipneumoniae (KpII) and K.variicola(KpIII).2 Previous research illustrated that KpI was the most frequent group, followed by KpIII and KpII.1,3 It’s difficult to distinguish KpI from KpII and KpIII using classic clinical laboratory examinations.4 Currently, the clinical importance of KpII and KpIII is overlooked , whilst approximately 20% of human isolates assumed to be K. pneumoniae are in fact K. variicola/ or K. quasipneumoniae.1 Clinically, Klebsiella pneumoniae is usually defined as classic klebsiella (Ck) and hypervirulent klebsiella (Hvkp) based on its invasiveness or virulence. The genetic research revealed two fatal virulence strains embedded in KpII (ST604 wcaG) and KpIII(ST616, wcaG), which links the relationship between bacteria virulence and its gene structure strain.5,6

Although the K.pneumoniae infection exists worldwide, no clinical case reported that a mixed infection caused by klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola would lead to patient death within a very short period. Here we report a rare case of a community-acquired bloodstream mixed infection caused by klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola leading to mortality within 72 hours. This case highlights a significant warning to community physicians and ICU clinicians to unexplained high fever, cough, or rapid deterioration of vital signs calling for vigilance against Klebsiella pneumoniae infection or mixed infection of klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola.

A 52-year old male was admitted to Jinyang Hospital at 21:20 on November 8, 2020 with unexplained fever, bellyache and headache for half hour. He had no medical history other than 5 years of history of type 2 diabetes and 7 years of history of Gout, and irregularly taking metformin, piroxicam and butazodine to treat diabetes and gout respectively. On admission, Doctors excluded the possibility of drug or food poisoning because the patient and his family members stated he had not taken any drugs or special food. Physical examinations revealed: Temperature of 38.7℃; blood pres¬sure 125/76 mmHg; heart rate 104/min; respiratory rate 20/min; pulse oxygen saturation 95% on room air; with no other physical signs presented. Laboratory data showed an abnormal of blood routine examination results (white blood cell (WBC) count of 5.46 x 109/L,87.3% neutrophils, 11.4% lymphocytes and 0.8% monocytes), the mildly increased C-reaction protein (CRP) and normal hepatorenal function parameters (Table 1 & 2) The main treatments included physical cooling, anti-inflammation with intravenous Ceftazidime (1gram per 8 hours).

|

Items |

Results |

Reference range |

|

WBC (x109) |

5.46x109 |

3.5-10 |

|

#NEUT (x109) |

4.77 |

1.8-6.3 |

|

%NEUT |

87.3% |

40-75 |

|

MONO (x109) |

0.04 |

0.1-0.6 |

|

%MONO |

0.8% |

3-10 |

|

#LYMBP(x109) |

0.62 |

1.1-3.2 |

|

%LYMBP |

11.4% |

20-50 |

|

RBC (x1012) |

5.85 |

3.5-5.5 |

|

HGB (g/L) |

166 |

114-163 |

|

%HCT |

49.9 |

35-50 |

|

PLT(x109) |

135 |

125-350 |

|

CRP mg/L |

11.94 |

0-10 |

Table 1 The blood routine examination and CRP results on admission

Patient was admitted to Jinyang Hospital, the blood sample was immediately collected and examined after admission. Blood routine and CRP results were acquired two hours after sample collection

|

Items |

Results |

Reference range |

|

TBIL(μmol/L) |

9.7 |

3.6-20.5 |

|

TP (μmol/L) |

60.6 |

65-85 |

|

ALB(g/L) |

41.00 |

40-55 |

|

ALT(U/L) |

23 |

9-50 |

|

AST(U/L) |

17 |

15-40 |

|

SCREA(μmol/L) |

82 |

57-90 |

|

UREA(μmol/L) |

7.2 |

3.1-8 |

|

GLU(mmol/L) |

18(postprandial blood sugar) |

7.8-11.1 |

|

K+(mmol/L) |

4.18 |

3.5-5.5 |

|

UA(μmol/L) |

441 |

210-420 |

Table 2 The liver and renal function parameters on admission

After admission, the blood sample was immediately collected and examined. Liver and renal function results were acquired about four hours after sample collection

However,all treatments failed to improve the patient’s symptoms. By 18:00 on November 9, 2020, the patient presented a high fever (41℃), diarrhea, and confusion. He was subsequently transferred to Intensive Care Unit of Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital. Physical examinations showed bleeding points scattered on abdomen, back and lower limbs, and lung wet rales were found. Laboratory examinations revealed there were the deteriorated hepatorenal function, clotting function and increased inflammation parameters such as C-reactive protein (CRP), Procalcitonin (PCT) and count of White blood cell (Table 3-5). The electrocardiogram and abdominal ultrasonography showed no significant abnormality (Figure 1,2), and the Chest radiograph showed the manifestations of inflammatory response (Figure 3).These laboratory examinations also excluded the diagnosis of infection of virus, mycobacteria, mycoplasma/chlamydia and autoimmune disease (Table 6). Classical bacteria culture of blood was examined after admission and showed the bacterial of klebsiella pneumonia (Table 7). After admission, the initial diagnosis considered immunity-acquired infection, and treatments included anti-inflammation (intravenous Vancomycin 1gram per 8hours + intravenous Meropenem 1gram per 6hours + intravenous caspofungin 70milligrams/initial dose), plasma exchange were immediately implemented on admission. Four hours later after admission, patient’s conditions deteriorated, with a decreased blood pressure and dyspnea with reduced oxygen saturation. Life support therapies including mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drugs were then conducted. During these treatments, other examinations (classical bacteria culture of blood, bone marrow biopsy and PMseq-DNA Pro High throughput gene detection) were conducted on second day after transfer. However, the patient's condition was further aggravated within following few hours, and at 13:00 on November 11, 2020, the patient suffered cardiac arrest and was declared clinically dead after several rescue efforts. The PMseq-DNA Pro High throughput gene detection was conducted on second day after transferring, results was acquired on November 13, 2020 and revealed the mixed infection of klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola (Figure 4). The bone marrow biopsy was examined on second day after transferring and supported the severe bacterial infection (Figure 5). Based on all parameters, we considered the diagnosis of severe community-acquired bloodstream mixed infection caused by klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola.

|

Items |

Results(1st) |

Reference range |

|

TBIL(μmol/L) |

19.4 |

3.6-20.5 |

|

TP (μmol/L) |

49.8 |

65-85 |

|

ALB(g/L) |

31.4 |

40-55 |

|

ALT(U/L) |

156 |

9-50 |

|

AST(U/L) |

182 |

15-40 |

|

SCREA(μmol/L) |

160 |

57-97 |

|

UREA(μmol/L) |

12.40 |

3.1-8 |

|

GLU(mmol/L) |

13.89 |

3.9-6.1 |

|

K+(mmol/L) |

3.22 |

3.5-5.5 |

|

UA(μmol/L) |

591 |

210-420 |

Table 3 The liver and renal function results after transferring from Jinyang Hospital to Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital

Patient was transferred from Jinyang Hospital to Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital on November 9, 2020, the blood sample was collected and examined after transferring. Liver and renal function results were acquired about four hours after sample collection

|

Items |

Results |

Reference range |

|

3P |

Negative |

Negative |

|

D-D (μg/ml) |

60.75↑ |

0~1 |

|

FDP (μg/ml) |

128.5↑ |

0~5 |

|

PT (sec) |

18.3↑ |

9.2~12.2 |

|

INR |

1.59↑ |

0.8~1.2 |

|

APTT (sec) |

67.6↑ |

21.1~36.5 |

|

TT (sec) |

23.4↑ |

14~21 |

|

Fbg ( g/l) |

22.58 |

1.8~3.5 |

Table 4 The clotting function parameters tested after transferring

Patient was transferred from Jinyang Hospital to Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital on November 9, 2020, the blood sample was collected and examined after transferring. Clotting function results were acquired one hour later after transferring

|

Items |

Results |

Reference range |

|

WBC (x109) |

1.20 |

3.5-10 |

|

#NEUT (x109) |

0.63 |

1.8-6.3 |

|

%NEUT |

52.5 |

40-75 |

|

MONO (x109) |

0.05 |

0.1-0.6 |

|

%MONO |

4.2 |

3-10 |

|

#LYMBP(x109) |

0.39 |

1.1-3.2 |

|

%LYMBP |

32.5 |

20-50 |

|

RBC (x1012) |

1.83 |

3.5-5.5 |

|

HGB (g/L) |

52.0 |

114-163 |

|

%HCT |

15.60 |

35-50 |

|

PLT(x109) |

10.0 |

125-350 |

|

CRP mg/L |

230.33 |

0-5 |

|

PCT |

>100 |

0-0.046 |

Table 5 The blood routine examination results on admission

After patient transferring from Jinyang Hospital to Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital, the blood sample was collected and examined after transferring. Blood routine, CRP, PCT results were acquired two hour later after transferring

|

Items |

Results |

Reference |

|

RSV-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

ADV-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

IFZA-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

IFZB-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

HPIVs-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

MP-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

CP-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

CBV-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

CAV-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

ECHO-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

LP-IGM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

2019-nCoV |

Negative |

Negative |

|

EB-DNA (copies/ml) |

<5E+2 |

<5E+2 |

|

EB-DNA |

Negative |

Negative |

|

CMVDNA DL(copies/ml) |

<5E+2 |

<5E+2 |

|

CMV DNA DX |

Negative |

Negative |

|

t1 |

Test method: Blotting |

|

|

A-PR3 |

Negative |

Negative |

|

A-MP0 |

Negative |

Negative |

|

A-GBM |

Negative |

Negative |

|

t2 |

Test method: Fluorescence |

|

|

cANCA |

Negative |

Negative |

|

pANCA |

Negative |

Negative |

Table 6 Results related to Virus, mycobacteria, mycoplasma/chlamydia and autoimmune disease

After patient transferring from Jinyang Hospital to Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital , the blood sample was collected and examined after transferring, parameters related to Virus, mycobacteria, mycoplasma/chlamydia and autoimmune disease were examined

|

Specimen |

Blood |

||

|

Equipment |

Phoenix100 |

||

|

Items |

Bacterial culture +Antimicrobial Susceptibility |

||

|

Results |

Klebsiella Pneumoniae |

||

|

Antibiotics |

MIC |

Results Interpretation |

Breakpoints |

|

Cefotaxime |

|

S |

S≤1;R≥4 |

|

Cotrimoxazole |

≤20 |

S |

S≤2/38;R≥4/76 |

|

Tigecycline |

≤0.5 |

S |

|

|

Levofloxacin |

≤0.12 |

S |

S≤0.5;R≥2 |

|

amikacin |

≤2 |

S |

S≤16;R≥64 |

|

Imipenem |

≤0.25 |

S |

S≤1;R≥4 |

|

Er Ertapenem |

≤0.12 |

S |

S≤0.5;R≥2 |

|

Cefepime |

≤0.12 |

S |

S≤2;R≥16 |

|

Ce Foperazone/sulbactam |

≤8 |

S |

S≤16;R≥64 |

|

Ceftriaxone |

≤0.25 |

S |

S≤1;R≥4 |

|

Ceftazidime |

≤0.12 |

S |

S≤4;R≥16 |

|

Cefoxitin |

≤4 |

S |

S≤8;R≥32 |

|

Cefuroxime axetil |

4 |

S |

|

|

Cefuroxime |

4 |

S |

S≤4;R≥32 |

|

Piperacillin/Tatabatam |

≤4 |

S |

S≤16/4;R≥128/4 |

|

Amoxicillin/clavulanate |

≤2 |

S |

S≤8/4;R≥32/16 |

|

ESBL |

Neg |

- |

|

Table 7 Results of bacterial culture of blood sample

Blood sample was properly collected and examined following the standards of bacterial culture. Results of bacterial and antimicrobial susceptibility were acquired after 24 hours later

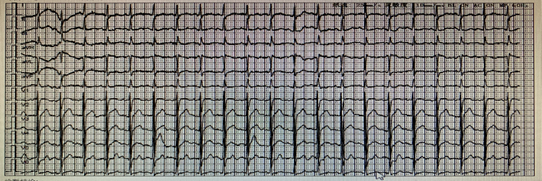

Figure 1 The electrocardiogram on November 8, 2020.

The electrocardiogram was performed after admission in Jinyang Hospital, results showed that Sinus tachycardia(140/min)and mild change of T wave.

Figure 2 The result of Abdominal ultrasonography on November 9, 2020.

The abdominal ultrasonography was conducted on November 9, 2020. results showed that Gallbladder wall thickening, left renal cyst;the sonograms of liver, pancreas, spleen and right kidney were normal.

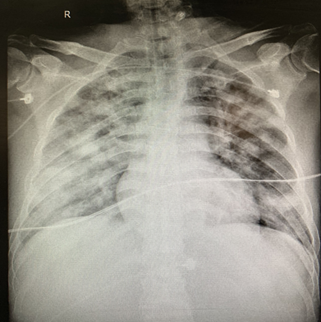

Figure 3 The Chest radiograph on November 8, 2020.

After admission in Jinyang Hospital, chest radiograph was performed, results showed that the manifestations of bilateral lung inflammation: The fuzzy bilateral lung markings, multiple patchy and patchy hyperdense shadows.

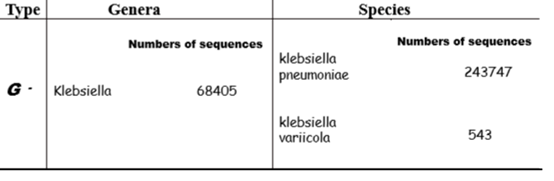

Figure 4 The PMseq-DNA Pro high throughput gene detection from blood sample.

To identify the pathogenic bacteria for bloodstream, the blood sample was collected on second day after patient transferring from Jinyan Hospital to Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital. And the gene detection of blood sample was performed. Results showed that the bacterial type is the G-, bacterial genera is Klebsiella, and there are 68405 of sequences number. Also, results revealed that there are two species of klebsiella: klebsiella pneumoniae and klebsiella variicola, their sequence number are 243747 and 543 respectively.

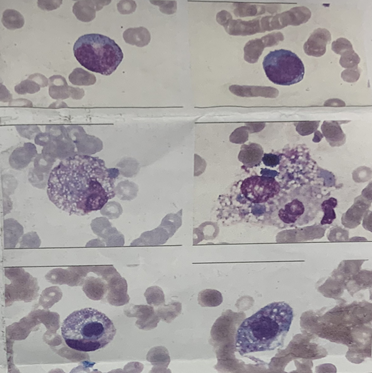

Figure 5 The bone marrow biopsy result on November 9, 2020.

The bone marrow biopsy was conducted on November 9, 2020. results was acquired on November 10, 2020 and showed there are a few scattered and unidentified cells and macrophages phagocytizing blood cells, which presented the typical hemophagocytosis and the manifestations of severe infection.

Klebsiella is a Gram-negative bacterium within the enterobacteriaceae family. It usually causes the opportunistic nosocomial infection or community-required infection among hospitalized patients or community people. Klebsiella pneumoniae is mainly colonized in human gut but also has been isolated from other body surfaces such as hand, face, and skin, even from other sources including water, plants and soil.1,7 Klebsiella pneumoniae infection has led to significant concerns because of its increasing incidence, varied manifestation and resultant mortality.8 It contains several subspecies manifesting with varied clinical performances. Recently, some severe infections caused by polygroups of klebsiella pneumoniae have raised significant questions for clinicians. As in this case study, a rare of mixed infection caused by klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella variicola brings patient the fatal effect within a very short period.

In this case, we excluded the possibility of poisoning of drugs and food. Moreover, the following laboratory examinations did not support the infection of virus, chlamydia, mycoplasma, fungal and parasite. We defined this case as community-required infection disease because the patient had no the history of hospitalization within several months. The bacteria culture of blood sample showed klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection, while the PMseq-DNA Pro High throughput gene detection for blood sample further revealed the infection sources including two phenotypes of genus klebsiella, klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella variicola. Therefore we considered the case as the mixed bloodstream infection of klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella variicola. Klebsiella bacteria colonization in human gut can cause infection when individual presents with immunodeficiency. Recent research revealed the diabetes is a significant risk factor for hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae infection and for causing serious complications.9-11 In this case, patient had the medical history of diabetes and gout, and treatments with piroxicam and butazodine to gout. His medical history could contribute to his underlying immunodeficiency and was possibly responsible for mixed bloodstream infection. Although there are more sequence numbers of klebsiella pneumoniae than klebsiella variicola from the blood sample detected, we consider that the klebsiella variicola played the more viral role to this disease progression and patient’s prognosis in this case because the klebsiella variicola associated with the more frequent cause of bloodstream infection and higher mortality.3,4

For clinicians, the current commonly method used to find infection pathogens is bacterial culture of sputum, urine, blood and other specimens. However, it is difficult to distinguish Klebsiella pneumoniae and its subspecies, which may delay diagnosis and treatment.4 As shown in this case, Klebsiella pneumoniae was found in blood culture and was sensitive to antibiotics used, but treatment did not respond well. Gene detection of blood sample identified Klebsiella pneumoniae and its subspecies. However, gene detection was performed on second day after the patient transferring (The third day after symptom onset, normally it needs 24-48 hours to acquire the test results), and patient's condition progressed rapidly, thus it did not provide a guide to treatment. This case suggests that early use of genetic detection may be helpful in determining infection pathogens and guiding treatment for complex infection diseases.

To date there is no consensus on the effective treatment of hypervirulent klebsiella infection. Recent clinical observations showed tigecycline and polymyxin display higher rates of treatment success than other antibacterial drugs such as carbapenem.12 Moreover, the combination of treatments is preferred to monotherapy in cases of severe infections13,14 Lacking the evidences of klebsiella variicola during the initial period in this case, the anti-infection treatments implemented for this patient contained anti-fungal, anti-virus and antibacterial drug across a broad-spectrum. As shown in this case and previous researches, treatments based on clinical experiences and classical methods displayed a poor clinical effect, although bacterial culture results showed klebsiella pneumoniae are sensitive to antibiotics used. Thus, this case further suggests that early introduction of genetic detection method may be more useful in diagnosing and instructing treatment for severe infection. In addition, tigecycline or polymyxin, or combination treatment of tigecycline and polymyxin should be tried in health-care patients who presented with suspected and severe community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae infection.9-14

Klebsiella pneumoniae subspecies can cause severe infection and bring the fast and fatal influence to health-care patients. When community-acquired infections occur in patients requiring health care and progress rapidly, we should consider the possibility of infection caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae subspecies or their confluence. Comparing to classic clinical laboratory methods, early introduction of genetic test is more beneficial to diagnosis and treatment. In addition, routine broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs may not be effective to the suspected pneumoniae subspecies infection, thus, tigecycline or polymyxin, or their combination strategy should be conducted as soon as possible to prevent its fatal effects.

This case report was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the family members of patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

This work was supported by Science and Technology Fund of Guizhou Provincial Health Commission (gzwjkj2019-1-067) and Doctor Foundation of Guizhou Provincial People's Hospital (GZSYBS [2019]04).

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors, and the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us. All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

We thank Dr Miaomiao ZUO for Proofreading for the manuscript.

©2021 Long, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.