MOJ

eISSN: 2381-179X

Case Report Volume 2 Issue 1

1PhD Community Health, Fresno County Department of Public Health, USA

2Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, USA

3Community Health, Fresno County Department of Public Health, USA

Correspondence: Jared Rutledge, Fresno County Department of Public Health, 1221 Fulton Mall, Fresno, Ca, USA, Tel 1 (559) 600-3474, Fax 1 (559) 600-7603

Received: January 12, 2015 | Published: January 27, 2015

Citation: Rutledge J, Williams V, Brewer H. Chikungunya occurrence among a religious Missions trip to Haiti in the summer of 2014 and implications for community health. MOJ Clin Med Case Rep. 2015;2(1):6-8. DOI: 10.15406/mojcr.2015.02.00008

As global travel becomes more common, the risk of spreading infectious diseases is increasing. Vectors too are spreading and becoming invasive species in environmental niches where they had previously been absent. The potential continues to grow for people to bring back diseases and infect local naive insect populations, which over time will increase the likelihood of the disease transmission occurring locally. This article evaluates the impact of a mission’s trip to Haiti and the return to a region of the United States that just recently became invaded by Aedes aegypti. The attack rate among the missionaries was approximately 20% (n=2), but this brings into question precautions that missionaries and other travelers will want to take upon return from tropical regions with endemic vector borne disease. Providers as well as travel clinics should educate patients regarding their viremic period and the potential to bring back diseases with them. While it would take hundreds of people to be viremic and to be bitten by the naive vector to establish local transmission, the preventative action is minor and would require travelers from endemic areas to continue to apply insect repellant for 7days after return from an endemic region.

Keywords: chikungunya, aedes aegypti, vector borne disease, haiti

CHIK-V, chikungunya (CHIK-V); A. aegypti, aedes aegypti; CMAD, consolidated mosquito abatement district

Background

Chikungunya (CHIK-V) is a single-stranded RNA alpha virus of the family Togaviridae, first isolated from mosquitoes and humans during an outbreak in Tanzania in 1952 to 1953.

The onset of symptoms of a CHIK-V infection is usually 3-7days after being bitten. Infection elicits an acute febrile and incapacitating Polyarthralgia typically affecting the hands and feet. Other manifestations include headache, myalgia, maculopapular rash, gastrointestinal involvement, and persistent rheumatologic symptoms.1 The exact pathogenesis that accounts for persistent joint symptoms is uncertain, but it has been proposed that joint involvement may have a relationship with predisposing genetic profiles such as HLA B27.2 Macrophage-derived products such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interferon-gamma, and macrophage chemo attractant protein-1 may be implicated in the damage of joint tissue. While fatalities associated with CHIK-V infection are rare, more severe clinical presentations have been observed in patients with underlying medical conditions and those that are elderly.3

As a vector for transmission of several tropical fevers, Aedes aegypti is known to have originated in Africa, but is now endemic to many tropical and subtropical regions worldwide.3 Epidemics of CHIK-V classically occur during the tropical rainy season and diminish as the dry season approaches. Only the female is responsible for blood meals, which is necessary for maturity of her eggs. In the United States, A. aegypti is found in the Southeast and to a lesser extent, parts of the Southwest, and has become well adapted to urban settings. It has a predilection for the human host as a source of blood meals, and readily breeds in flowerpots and other vessels capable of holding water, which are ideal environments for egg laying. A single mosquito may be able to infect multiple persons, as this species will move to another host if feeding is interrupted; it is an aggressive, daytime biter, both indoors and outdoors.

Purpose of the study

With the presence of the vector that spreads CHIK-V (A. aegypti) in Fresno County,4 there is a concern that residents, who travel abroad to regions that are endemic for diseases such as Dengue or CHIK-V, may import the disease and infect local mosquito species, which could result in local transmission of diseases that have previously not presented in the region. This has already taken place in regions of the US such as Florida.5 The purpose of the study was to evaluate the attack rate, onset times, and activities of a small group of missionaries who returned from a region endemic for CHIK-V and evaluate the potential for medical and public health action.

Significance

The risk of importation of CHIK-V into new areas is of concern due to high attack rates associated with recurring epidemics, high level of viremia in infected humans,3 and the sporadic presence of those vectors responsible for transmission in Fresno County. The incubation period of CHIK-V is typically 3-7days, with abrupt symptoms. Shortly after the onset of fever, a majority of infected persons develop severe, debilitating polyarthralgia. On average, 2years after initial infection nearly 43-75% of CHIK-V positive patients report prolonged or late-onset symptoms. These rheumatologic and neurological implications carry a significant economic burden in the fields of healthcare.6 The annual individual and population economic burden of rheumatic conditions is growing in developed countries, primarily due to the aging population rather than costs per case.7

Between the years of 1997 and 2005, mean annual ambulatory and prescription expenditures for adults with arthritis far exceeded the rate of medical inflation, offsetting a relative decline in inpatient costs. Projected growth in this patient population suggests that these expenditures will continue to rise.8 The plausibility of increased transmission by the local Fresno mosquito population in the presence of infected travelers warrants public health intervention, namely, education for post-exposure prophylaxis and control measures such as the continued application of repellant. By developing a protocol for vector control and limiting exposure, the economic burden due to long-term CHIK-V infection squealae can be greatly alleviated.

Scenario

The Central San Joaquin Valley in California has regularly been referred to as the Bible Belt of California.9 In that evangelical religious tradition, there are several churches and faith based organizations that send missionaries abroad to developing countries to provide aid, support, build infrastructure, and share their religion. All participants were given information from a local organization regarding Dengue, CHIK-V, and Yellow Fever prior to leaving for the mission trip.

In the summer of 2014, one group consisting of 10members of a local congregation went to Haiti to provide support and share their religion. The regions that were visited were Maissade, Port Au Prince, and Hinche. The duration of the stay was 9days and 8 nights. Upon return, 2members of the congregation had fallen ill and one sought medical care. The primary care physician ran Dengue and CHIK-V serology due to the symptoms and travel history. The local health department was not notified until the results were returned from the laboratory, which limited the public health action of mosquito surveillance to the area surrounding the index patient’s house.

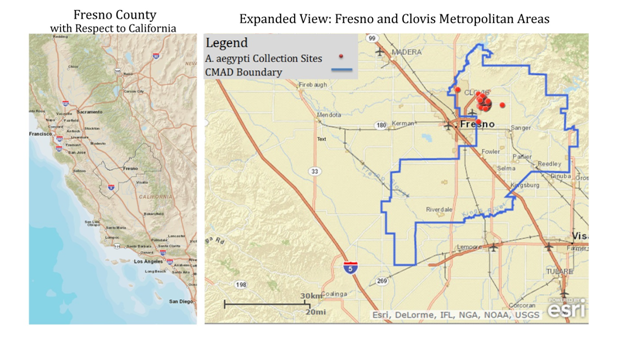

The local health department was notified and the epidemiologist contacted the patient to get a list of participants and the name of the church. All participants were contacted and requested to participate. If they selected to participate and sign the informed consent document they were given a free test for CHIK-V and Dengue as well as asked a series of questions. Mosquito abatement was also contacted to set up mosquito traps around the residence of the suspected cases. The distribution of A. aegypti in Fresno County is depicted in Figure 1.

Descriptive statistics A total of 8 out of 10 (80% participation) missionaries selected to participate. Those that opted not to participate did so because they resided outside of the health jurisdiction of the epidemiologist conducting the investigation. The 2patients that did not select to participate did indicate that they were neither symptomatic nor ill at the time of the interview or during the trip, however they did not answer the questions from the questionnaire nor did they provide blood for the serological test.

Due to the structured aspect of this trip, the group participated in all of the same activities and experienced the same environmental exposures. Activities included training teachers, working at the orphanage, playing with the children, conducting home visits, attending church meetings, and meeting with small groups of children. Of the 8 participants, 7 completed the serology tests for both CHIK-V and Dengue. The attack rate based on confirmed cases was 10% (n=1), but the other patient who was ill with joint pain, fever, rash, and headache, did not submit to a blood test, and it was concluded this was a highly suspect case , thus yielding an estimated attack rate of 20% (n=2). Table 1 & Table 2 contain the distribution of risk factor, exposures, and symptoms as reported by the missionaries.

Activity |

Yes |

No |

Unknown |

Use of Insect Repellant |

8(80%) |

0(0%) |

2(20%) |

Mosquito Bites Per Day |

8(80%) |

0(0%) |

2(20%) |

Mosquito Bites in the Urban Environment |

1(10%) |

2(20%) |

7(70%) |

Mosquito Bites in the Rural Environment |

8(80%) |

0(0%) |

2(20%) |

Previous Trips to Haiti |

4(40%) |

4(40%) |

2(20%) |

Previous Trips to Other Caribbean Countries |

2(20%) |

6(60%) |

2(20%) |

Table 1 Participant exposures and risk factor analysis

*Only 1 participant reported using insect repellant once per day and that participant was not symptomatic.

Symptoms |

Yes |

No |

Unknown |

Joint Pain |

2(20%) |

8(80%) |

0(0%) |

Fever |

3(30%) |

7(70%) |

0(0%) |

Rash |

3(30%) |

7(70%) |

0(0%) |

Chikungunya Serology |

1(10%) |

6(60%) |

3(30%) |

Dengue Serology |

0(0%) |

7(70%) |

3(30%) |

Table 2 Distribution of symptoms among participants

Onset of illness occurred on the day of return to the US, for both cases, which implicates they were bitten in the highly urban region of Port Au Prince prior to the application of their insecticide, given the incubation of the illness. Considering the urban environmental preference of A. aegypti, Port Au Prince is a plausible site of disease transmission.10

The mosquito capable of spreading CHIK-V, Dengue, and Yellow Fever is sporadically present in California. Fresno County is one of the regions where the mosquito is present,4 see Figure 1 for the distribution of the A. aegypti in Fresno County. Missionaries returning from CHIK-V endemic areas could potentially pose a risk to local residents by bringing back a virus and infecting the local mosquito population.

Viremia with CHIK-V infection spans a brief period, typically 2-6days11,12 and this is the time that the patient poses the greatest risk of propagating transmission, to the mosquito vector, as well as other people that may come into contact with the patient’s infected blood. In addition to the health information that missionaries are given prior to visiting these areas they should also be encouraged to continue application of the mosquito repellant once they return. This additional could potentially reduce the risk of infection of local mosquito species.

Figure 1 Sites within Fresno County where A. aegypti have been isolated January 1, 2014-December 31, 2014, consolidated mosquito abatement district (CMAD).

In addition to the initial outbreak, other individuals have been reported to the local public health department that was positive for CHIK-V. In the investigation of these cases, it was discovered that many other household members were sick too, but they expressed no desire to get tested due to the lack of specific treatment for CHIK-V and the low mortality rate. While the probability of experiencing symptoms is high with this disease,7 it could go under-reported due to the low mortality rate and lack of specific treatment.

As a result of the outbreak among the mission’s trip to Haiti, Fresno County Department of Public Health has developed specific guidance for travel clinics and faith based organizations designed to give them this additional education. The County Health Department will be educating and distributing these materials to providers, travel clinics, and faith based organizations in 2015 in an effort to reduce the risk of infecting local mosquito species capable of transmitting this virus.

None

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2015 Rutledge, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.