MOJ

eISSN: 2381-179X

Case Report Volume 11 Issue 1

Internal Medicine Department, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center at Shreveport, USA

Correspondence: Rhett Orgeron, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center at Shreveport, 1501 Kings Hwy, USA, Tel (504)432-0637

Received: January 04, 2021 | Published: January 25, 2021

Citation: Orgeron R, Khoury RA, Hirani S, et al. Complications of refractory juvenile dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. MOJ Clin Med Case Rep . 2021;11(1):8-12. DOI: 10.15406/mojcr.2021.11.00371

We present a 29-year-old male with a history of treatment resistant juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM). The patient was admitted for complaints of nausea, diarrhea and abdominal pain and was subsequently found to have intestinal perforation on imaging. The patient had also exhibited classic dermatologic findings alongside rare dermato-pathological manifestations of JDM on examination; likely consequences of his underlying disease process. This case serves to present these rare findings and analyze the similarities of JDM and adult dermatomyositis (DM). In addition, overall diagnosis and treatment of resistant/severe JDM is explored. High clinical suspicion alongside an interdisciplinary approach is warranted for such patients given their extensive risk factors for future complications.

Keywords: juvenile dermatomyositis, perforation, calcinosis cutis, treatment, review

JDM is a rare condition that some clinicians may never encounter. It is known to affect about three in one million children every year and tends to affect females approximately twice as frequently as males, although this ratio may vary depending on the area studied.1 Previous studies have shown a bimodal distribution in the age of onset, with girls developing symptoms most frequently at ages 6 and 12 and boys at ages 6 and 11.2-3 Incidence studies conducted in the United States showed an annual incidence rate of 3.4 for white non-Hispanics, 3.3 for African American non-Hispanics, and 2.7 for Hispanics.3 The pathogenesis behind JDM is thought to be from autoimmune systemic vasculopathy with signs and symptoms manifesting in a wide variety of organ systems, including integumentary, musculoskeletal, pulmonary, cardiac and gastrointestinal systems.4

There are several different clinical manifestations of JDM outside the typical presentation that we will analyze throughout this case. Notably, our patient reported a history of resistance to first-line therapies of JDM and recurrent flare-ups of disease over several years, which most likely caused his unusual clinical presentation of extensive calcinosis cutis and lipodystrophy. Furthermore, very few cases of small intestinal perforation have been documented in adult patients diagnosed with JDM at a younger age. His recent steroid therapy alongside poorly controlled JDM offered a unique opportunity to create a differential diagnosis for the cause of this severe complication and allow for educational reflection in the diagnostic work-up.

We report a 29-year-old Caucasian male who presented to his rheumatology clinic appointment complaining of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, lower abdominal pain and generalized muscle weakness. Patient was subsequently sent to the emergency department and admitted to the internal medicine service with rheumatology consulted. His past medical history is significant for JDM that was diagnosed approximately 5 years prior to presentation. Regarding his diagnosis of JDM, the patient and his mother reported that his first symptom occurred at age 15, when he had episodes of muscle weakness and failure to thrive. It took years of relapsing symptoms and repeated primary care and hospital visits before he was evaluated for a rheumatologic disease. This is not an uncommon phenomenon given the rarity of the disease and its wide clinical presentation. A previously conclusive diagnosis was made given the patient's history, symptoms, positive antibody test (Anti-Mi-2 antibody) and deltoid muscle biopsy proving JDM (obtained at outside hospital with exact pathological report unknown). He was screened for malignancy at the time of diagnosis, but work-up was largely unremarkable. The patient had a polycyclic illness course with recurrent episodes of extremity muscle weakness and fatigue documented over the past three years.

His medications prior to admission included prednisone, methotrexate, folic acid, and pantoprazole in addition to monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusions. For several years, pt was continuously treated with 25mg methotrexate weekly and 1 mg folic acid daily. Corticosteroids were prescribed in varied doses (40-60 mg) and tapered down in between flare-ups; his overall steroid usage spanned approximately three years. After repeated rheumatology visits, rituximab was initiated, but during the infusion the patient developed an allergic reaction. 50mg azathioprine was prescribed and later increased to 100mg, but was held after skin infection developed in his axilla and abdomen. IVIG infusions were begun and scheduled every two weeks. His past surgical history was significant for a transiently placed PEG tube secondary to dysphagia that had subsequently resolved. Upon further questioning, there was no family history of autoimmune disease or malignancy reported by the patient or immediate family. Social history was non-contributory as the patient denied use of alcohol, tobacco or drug use.

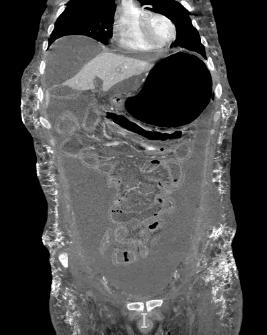

Upon performing the physical examination, multiple cutaneous lesions and disease-specific features were noted. The head and neck exam revealed an erythematous heliotrope rash over the bilateral eyelids (Figure 1). Flaky scales likely representing seborrheic keratosis were identified over the scalp and forehead. Inspection of the lower neck/upper chest revealed an erythematous V-sign rash (Figure 2). Posterior neck and upper back examination revealed an erythematous rash consistent with the shawl sign. Extremity examinations revealed multiple subcutaneous lipomas of the proximal upper extremities in addition to Gottron’s papules on the bilateral metacarpophalangeal joints (Figure 3). Closer examinations of the digits revealed vascular periungual changes noted on the capillary nail beds. Lower extremity examinations revealed erythematous lesions on the extensor surfaces of the bilateral knees representing Gottron’s sign alongside skin changes of the lateral thighs representing holster sign. Muscle strength was 3/5 in both the upper and lower extremities. Cardiopulmonary examination was significant for tachycardia, while heart and lung sounds were normal. Abdominal examination was significant for nonspecific tenderness and guarding with widespread/diffuse calcinosis cutis extending into the bilateral flanks (Figures 4,5). Vitals on admission were notable for a heart rate of 123beats/minute, blood pressure of 134/78mmHg, temperature of 98.9F and oxygen saturation of 98%. Laboratory examination revealed leukocytosis, mild anemia, hypokalemia and a normal creatine kinase.

During the course of this admission, the patient had increasing nausea, vomiting, and diffuse abdominal pain prompting a computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast (day 2). Once completed, the CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis revealed ischemic bowel with intraperitoneal free air and fluid, compatible with bowel perforation. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a proximal jejunal perforation and approximately 3 cm of small bowels were resected. On day 5 of admission, the patient developed acute hypoxemic respiratory failure when his oxygen saturation dropped to the low 70’s. The patient was subsequently intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and treated for probable aspiration pneumonia. The patient was given a spontaneous breathing trial on day 8 and was briefly extubated. Unfortunately, the patient could not clear his secretions and rapidly progressed to acute hypoxemic respiratory failure once again requiring repeat intubation. Due to a history of mucus plugging, failed extubation and poor pulmonary hygiene, the patient underwent a tracheostomy with a tracheostomy placement. The patient was extubated and tolerated a T-piece trial successfully. IVIG was continued and prednisone was gradually tapered. He was transferred to internal medicine where he continued to improve, as rheumatology and general surgery followed from the periphery. Sadly, on day 17 of admission the patient was found to have a brisk bleed from his tracheostomy site and shortly after became unresponsive and pulseless. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, but return of spontaneous circulation was not achieved and cause of death was likely secondary to hemorrhagic shock.

Of all the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (JIIM), JDM is the most frequently reported and the best studied. Although its clinical features are diverse, multiple unique signs, symptoms, and antibodies have been identified. Given this patient's young age of presentation and delayed onset of diagnosis, it is important for clinicians to be familiar with features of JDM for prompt diagnosis. Due to the numerous similarities between JDM and adult DM, Table 1 summarizes the prevalence of traits in JDM in comparison to adult DM to further expand on the signs and symptoms that may be encountered in JDM. Shah M et al reported proximal muscle weakness, Gottron’s papules and heliotrope rash as the most commonly seen amongst JDM cases given that these are defining features of the disease. Other musculoskeletal and cutaneous features that were present in those studied included myalgia (60.5%), arthralgia (57.7%), contractures (54.8%), periungual capillary abnormalities (78.8%), malar rash (73.3%) and photosensitivity (46.9%).5 Constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, fever, and weight loss were seen as well. Dysphonia, chest pain, and dysphagia were the most common pulmonary, cardiac, and gastrointestinal symptoms, respectively. The patient we present encompasses both common manifestations alongside rare complications as byproducts of his underlying JDM.

|

Features |

DM |

JDM |

Comments |

|

Mean age at diagnosis |

51.9 |

7.4 |

Median age 50.7 and 7.1 respectively |

|

Gender4 |

Female > male |

Female > male |

|

|

Malignancy4 |

7-30% |

No clear association with malignancy |

|

|

Mortality16-18 |

Variable |

0.5-2.5% |

|

|

Neck muscle involvement |

20.8% |

50% |

|

|

Myalgia |

71% |

59% |

|

|

Distal muscle weakness |

7% |

45% |

|

|

Asymmetric weakness |

4% |

11% |

|

|

Subcutaneous calcifications |

2.1% |

37.5% |

|

|

V-sign rash |

36% |

29% |

|

|

Shawl sign rash |

22% |

19% |

|

|

Mechanic hands |

33% |

7% |

|

|

Raynaud’s phenomenon |

40% |

9% |

|

|

Pulmonary4 |

|||

|

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) |

37% |

5% |

|

|

Antibodies19-24 |

|||

|

ANA |

44% |

41% |

- Nonspecific - Negative ANA associated with increased risk of malignancy in DM |

|

Anti-Jo1 |

40% |

1.4-5% |

- Associated with anti-synthetase syndrome. - The prevalence of ILD in anti-Jo1 positive patient cohorts has been found to be 86% |

|

Anti-Mi2 |

20% |

4-10% |

- Associated with hallmark cutaneous features and mild muscle disease. - Carries good prognosis |

|

Anti-p155 (anti-TIF1γ) / anti-TIF1α |

13-21% (Strong association of malignancy in DM) |

23% (No association of malignancy in JDM) |

- Strong association with cutaneous involvement |

|

Anti-NXP2 (p140 or MJ) |

1.6%-30% |

11-23% |

- Associated with a more severe disease course in JDM. - Both associated with increased risk of calcinosis |

|

Anti-MDA5 |

19-35% (Associated with clinically amyopathic myositis [81%] and rapidly progressive ILD [74%]) |

Rare |

- Carries a poor prognosis |

|

Anti-SAE |

8.4% (Associated with amyopathic myositis) |

Antibody has not been identified in JDM cohorts to date |

|

|

Anti-SRP |

Rare (Associated with a |

Antibody has rarely been identified in JDM cohorts |

Table 1 A comparative analysis of the widespread features that may be seen in DM or JDM.

DM, dermatomyositis; JDM, juvenile dermatomyositis; ANA, antinuclear antibody; Anti-Jo1, antihistidyl transfer RNA synthetase; Anti-Mi2, a nuclear helicase protein; Anti-TIF, antitranscription intermediary factor; Anti-NXP2, antinuclear matrix protein 2; Anti-MDA5, antimelanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; Anti-SAE, anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 activating enzyme; Anti-SRP, antisignal recognition particle

The presented patient with JDM had complained with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain. The patient was subsequently found to have an intestinal perforation on CT of the abdomen and pelvis that required immediate surgical intervention. Although intestinal perforation is a rare complication, there have been a few reports in patients with JDM.6-7 The pathophysiology of gastrointestinal complaints and ulceration in JDM is thought to be the result of underlying chronic vasculopathy.7 This vasculopathy may manifest as acute vasculitis or chronic endarteropathy, depending on the presentation. A case report by Mamyrova et al. examining the underlying histopathology of late-onset bowel perforation in two patients suffering from JDM appears most similar to our patient’s scenario. The study supports chronic endarteropathy as the probable cause of bowel ischemia and resultant perforation in JDM patients with late onset bowel perforation.7 Two studies have concluded that the underlying histopathology of bowel ischemia/perforation is likely secondary to vascular occlusion from intimal hyperplasia, fibrin thrombi and endothelial proliferation.7-8 Unfortunately, a histological examination was not completed on our patient’s resected bowel, so the exact pathological cause of his perforation remains questionable. Lab records over several rheumatology clinic visits demonstrated persistently elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase, C-reactive protein, and total creatinine kinase that could have potentially resulted in severe vasculopathy. Of note, during a DM flare-up one year ago, the patient additionally reported bloody bowel movements. Subsequent EGD revealed a pre-pyloric antral ulcer and multiple duodenal ulcers while colonoscopy showed no obvious source of bleeding. It should be noted that our patient was receiving prednisone for several years prior to presentation. Chronic glucocorticoid therapy must be considered in the differential etiology of his jejunal perforation, as it is likely an exacerbating factor. Refractory JDM with underlying endarteropathy alongside a history of chronic steroid use were likely the underlying factors resulting in this late onset intestinal perforation seen in our patient.

Another cutaneous manifestation noted in our patient is calcinosis cutis (Figure 4), which is simply the formation of calcium deposits in soft tissues. This finding is more commonly reported in cases of JDM rather than adult DM, with one study noting its prevalence in 43% of cases.9 The pathophysiology is multifactorial and poorly understood, but it is thought to be caused by a combination of chronic inflammation alongside genetic and environmental factors.10 In a study analyzing the risk factors associated with calcinosis in JDM, the overall incidence of calcinosis cutis was noted to be increased in patients with more severe disease manifestations or in those taking one or more immunomodulators.9 Subcutaneous calcinosis is therefore a sign of more advanced disease and indicates an overall poorer prognosis. Our patient presented with diffuse abdominal subcutaneous calcinosis with a distribution that extended into the lower chest, flanks and pelvic area (Figure 5). These underlying, severe calcium depositions formed an exoskeleton that is typically seen with treatment-resistant cases.11-12

Figure 5 Diffuse calcinosis cutis in the abdominal wall on CT abdomen/pelvis (coronal view and tissue window).

Our patient’s extensive presentation and subsequent clinical hardships ultimately stemmed from his early onset of disease and history of poor response to initial JDM therapy. Resistance to common first-line therapies such as glucocorticoids and methotrexate (MTX) are not uncommon. Fortunately, there are second-line therapies that may be used in such refractory cases. Rituximab has shown evidence of positive clinical outcomes in patients with polymyositis (PM), adult DM and JDM. A 2018 study supports the use of both Rituximab and Cyclophosphamide for the improvement of skin manifestations and overall inflammation in patients with refractory/severe JDM.13 Due to our patient’s prior and extensive resistance to steroids, MTX and Rituximab, rheumatology had to rely on a different strategy to achieve symptom resolution. Many studies have demonstrated that intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is an effective albeit expensive alternative. Dalakas et al. performed a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fifteen cases of resistant adult DM treated with IVIG. The study found that those treated with both prednisone and adjuvant IVIG showed clinical improvement in strength and increased muscle fiber diameter on repeated biopsies.14 Calcineurin inhibitors, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, are also an acceptable treatment in refractory DM, particularly in cases complicated by interstitial lung disease (ILD).15 The treatment of adult DM or JDM is similar, and choosing an agent depends cumulatively on the overall severity of the presentation and the underlying response. Escalation of therapy should be made promptly and involvement of a multidisciplinary team for a better overall decision making approach is warranted.

JDM is a relatively rare disease that is difficult to recognize given its variable presentation and spectrum of manifestations. This case report serves to explore classic and common JDM findings, as well as emphasize some of the late and rare complications that may occur with refractory/severe JDM. It is imperative to obtain a thorough clinical history alongside performing an extensive examination on such patients. In particular, those with a history of JDM should be carefully assessed when presenting with any GI complaints. Those with a history of refractory JDM, chronic disease course and/or history of steroid therapy carry a high risk for life-threatening complications. In such patients, an aggressive diagnostic initiative paired with an intense interdisciplinary approach is warranted. Although a rare disease, our case highlights the opportunity to research future avenues addressing diagnostic and treatment challenges, particularly in refractory disease.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

None.

None.

©2021 Orgeron, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.