MOJ

eISSN: 2471-139X

Case Report Volume 7 Issue 5

1Medical University, Varna, Bulgaria

2SBAGAL, Varna, Bulgaria

3“Vita” Multidisciplinary Hospital for Active Treatment, Sofia, Bulgaria

4Medical center of assisted reproduction “Varna”, Bulgaria

Correspondence: Ingilizova G, “Vita” Multidisciplinary Hospital for Active Treatment, Sofia, Bulgaria, Tel +359887204480

Received: September 13, 2020 | Published: October 16, 2020

Citation: Kovachev E, Ingilizova G, Anzhel S, et al. Molar pregnancy – case presentation of 23-year old pregnant women with partial molar pregnancy. MOJ Anat Physiol. 2020;7(5):150-153. DOI: 10.15406/mojap.2020.07.00306

Molar pregnancy occurs 1-2 per 1000 pregnancies, resulting in improper fertilization. Partial mole is a result of fertilization of a haploid normal oocyte with two spermatozoa simultaneously, with the formation of a zygote with a triploid set of chromosomes. Only in around 25% of cases is a variant with euploid fetus (46XX/XY). Several factors determine the prognosis of the fetus in partial molar pregnancy, such as karyotype of the fetus, size of the area with hydropic degeneration of the placenta, rate of hydropic degeneration and manifestation of fetal anemia or other obstetric complications such as preeclampsia, thyrotoxicosis and vaginal bleeding. The authors present a clinical case of partial molar pregnancy with death fetus and classical clinical picture of the pregnant women with excessive hCG values, teca lutein cysts and vaginal bleeding. The available modalities for treatment are discussed, focused on vacuum curettage as the treatment of choice with lesser risk of complications and impact on the future fertility.

Keywords: molar pregnancy, ultrasound findings, prognosis, treatment

Molar pregnancy (molahydatidosa) belongs to a group of diseases classified as gestational trophoblastic disease resulting from abnormal fertilization.1–3 Molar pregnancy is divided to two types - complete and partial, based on distinctive histopathological features and genetic abnormalities.3 Pathogenetically it is a complete or partial trophoblastic proliferation (of cyto- and syncytiotrophoblasts) with hydropic degeneration of the placental villi.

Complete molar pregnancy usually occurs when an egg without maternal chromosomes is fertilized by a single sperm, with a subsequent duplication of its DNA, resulting in a 46, XX paternal karyotype. About 10% of cases are 46, XY or 46, XX, resulting from the fertilization of an "empty egg" with two haploid spermatozoa. Abnormal fertility is associated with a maternal autonomic recessive mutation, most commonly NLRP7 on chromosome 19q, leading to recurrent molar pregnancies. As a result, hydropic trophoblastic degeneration and lack of embryonic structures develop.4,5

A rare complication with a frequency of 0.005-0.01% of all pregnancies is the presence of a twin pregnancy with a partial molar pregnancy and a concomitant normal fetus.6 Partial mole is a result of fertilization of a haploid normal oocyte with two spermatozoa simultaneously, with the formation of a zygote with a triploid set of chromosomes (69 XXX, 69XXY or 69 XYY) and is most often associated with the development of an irregularly shaped fetus.7 A possible variant is also a partial hydropic degeneration of the placenta with a fetus with a diploid chromosome set.8 Not infrequently, partial molar pregnancy remains undiagnosed in cases with first trimester pregnancy loss in the form of incomplete or missed abortion. In less than 25% of cases, partial mole occurs with the development of a euploid viable fetus, with the following options possible: most often it is a twin pregnancy, with one gestational sac containing normal fetus with normal placenta and the other one with a complete molar pregnancy; the second type is a twin pregnancy with one of the fetuses being normal with a normal placenta and the other sac having an incomplete mole.9 The rarest phenomenon is a singleton pregnancy with a chromosomally normal fetus and a partial molar placenta.10 Parveen et al.6 reported a case of partial molar pregnancy with normal karyotype of the fetus ending with a live birth on term.

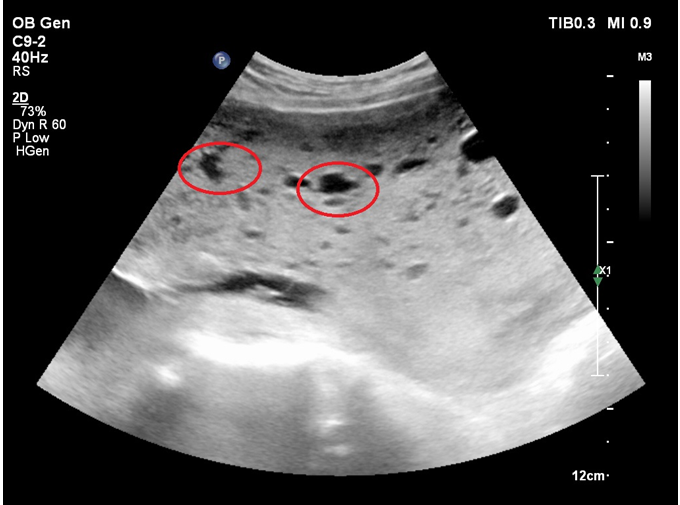

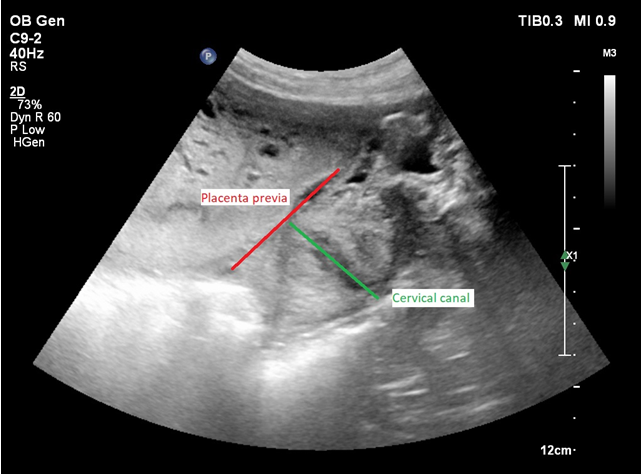

This is a 22-year-old lady, pregnant at 16 weeks of gestation who is admitted to SBAGAL with evidence of dead fetus in utero and suspected partial molar pregnancy with hCG>10,000IU/ml and vaginal bleeding. Two years ago the mother had normal birth of a healthy fetus from another partner. The ultrasound examination revealed a dead fetus with evidences of maceration, with a CRL of 78.83, corresponding to 14 gestational weeks, which is less than expected term of amenorrhea (Figure 1). A large placental mass with a diffuse multicystic structure is visualized, centrally localized above the OICC (Figure 2 & 3). Right ovary - with increased size and with the presence of multiple theca-lutein cysts sized between 4-5 cm (Figure 4).

Figure 1 Transabdominal 2-dimensional ultrasound - Dead fetus with CRL 78.83 (14 g.w.), not corresponding to amenorrhea. Cystic oedema of the head due to maceration can be clearly visualized (marked).

Figure 2 Transabdominal 2D ultrasound showing the placenta with evidence of diffuse hydropic degeneration (cystic structures are circumscribed).

Figure 3 Transvaginal 2D ultrasound - Centrally localized placenta previa, covering the internal os of the cervical canal.

Figure 4 Transabdominal 2D ultrasound showing theca-lutein cysts in the right ovary (more than one cystic structure in the ovary above 3cm).

After discussion by a medical commission, the patient was hospitalized and prepared for termination of pregnancy on medical grounds. Two bags of blood were provided preoperatively. Under endotracheal intubation, vacuum aspiration and ultrasound-guided curettage were performed in an operating room, ready for emergency laparotomy if needed. Before the procedure (6 hours) a fast osmotic dilator was placed in the cervical canal, with realized dilatation up to 3.5cm. Vacuum aspiration of the placental mass was performed under ultrasound control. The fetal parts were evacuated with the help of a grasping clamp. A revision of the uterine cavity was performed with a metallic curette. The procedure was performed under oxytocin infusion and intramuscular application of prostaglandins at the end of the evacuation (Figure 5). Smooth postoperative period. Negative hCG values were documented at follow-up 4 weeks after evacuation.

A significant risk factor for the development of complete molar pregnancy is the age of the mother. Compared with the risk in women aged 21 to 35 years, the risk is 1.9 times higher for women <21 years and> 35 years, and 7.5 times higher for women>40 years, including 1 in 3 pregnancies for women>50 years. However, such a dependence is not established with regard to the risk of developing a partial mole. Partial molar pregnancy is more common in women with a history of irregular menstruation, miscarriage and oral contraceptives for more than 4 years, while ethnicity, dietary factors and ovulation induction are not associated with an increased risk.

Complete molar pregnancy is most often presented by vaginal bleeding at 6 - 16 weeks of gestation in 90% of cases. Other classic symptoms, such as higher than expected gestational age (28%), hyperemesis (8%), hyperthyroidism and trophoblastic embolization (<1%) are less common in recent years due to earlier diagnosis, as a result of the widespread use of high-quality ultrasonography and quantitative measurement of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Bilateral teca-lutein cysts and ovarian enlargement occur in approximately 15% of cases, with hCG levels often >100,000 mIU/mL.11

Partial molar pregnancy is also associated with a similar clinical manifestation. Less than 10% of cases have hCG levels > 100,000 mIU / mL. More than 90% of cases occur as an incomplete or delayed abortion and the diagnosis is usually made only after histological examination of the evacuated material.12

In addition to the typical clinical manifestation as a result of excessive hCG production, molar pregnancy is characterized by a specific ultrasound picture. Typical ultrasound manifestations of a complete molar pregnancy include the visualization of a diffuse, multiscystic and often hypervascular intrauterine mass ("snowstorm" or "honeycomb" type) with no fetal tissues. Partial molar pregnancy may present as a localized placental abnormality with a living embryo, spontaneous intrauterine fetal death, or the presence of an empty gestational sac (blighted ovum).13,14 Some authors propose the following ultrasound criteria for specific findings of partial molar pregnancy as a ratio of transverse to anteroposterior diameter of the gestational sac >1.5 and cystic changes in the placenta and/or irregularity of the contour of the decidua, placenta or myometrium.15

During the first trimester, the frequency of diagnosing a complete mole is higher than that of a partial mole, increasing with advancing of gestational age. Fowler et al.16 analyzed 378 ultrasound-proven molar pregnancies, demonstrating the accuracy of the ultrasound diagnosis in 200 of 253 (79%) complete hydatidiform moles and 178 of 616 (29%) partial hydatidiform pregnancies.

Several factors determine the prognosis of a fetus in a partial molar pregnancy, such as the karyotype of the fetus, the size of the area with hydropic degeneration of the placenta, the rate of hydropic degeneration and the manifestation of fetal anemia or other obstetric complications such as preeclampsia, thyrotoxicosis and vaginal bleeding. In singleton pregnancies with dizygotic normal fetus with partial molar placenta, pregnancy development depends on the genesis of placental degeneration, from amniotic diploidy to chorionic villus triploidy, which determines two different types of placental pathology: focal and diffuse partial degeneration.17 In most cases, however, the diagnosis of a partial mole is in the case of intrauterine fetal death. Despite early diagnosis of complete mole, which leads to fewer complications, no concomitant reduction in the incidence of post-molar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) has been observed.18 Approximately 10% to 20% of women with a complete molar pregnancy and 0.5% to 11% with a partial molar pregnancy will continue to develop persistent, invasive gestational trophoblastic disease, including invasive mole, choriocarcinoma, or placental trophoblastic tumor.16

In case of a suspected diagnosis of molar pregnancy on the basis of medical history, physical examination, hCG level and ultrasound findings, the physician should assess the presence of medical complications (anemia, preeclampsia, hyperthyroidism) which have to be treated. Key laboratory tests include: complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, thyroid function test, urine test, chest x-ray, an electrocardiogram, coagulation status and blood group with rhesus factor.

In patients who wish to maintain fertility, vacuum curettage is the preferred method of treatment, regardless of the uterine size. Maximum dilatation of the cervical canal and aspiration with a 12- to 14-millimeter cannula under ultrasound control are recommended. As the risk of excessive bleeding increases with the size of the uterus, it is necessary to provide at least two sacks of blood preoperatively in cases with uterine size >16 gestational weeks.

Hysterectomy is an alternative in patients who do not wish to maintain fertility or who are at increased risk of developing post-molar gestational trophoblastic disease. Adnexa can be preserved bilaterally, even in the presence of theca-lutein cysts. In addition to the evacuation of molar pregnancy, hysterectomy provides permanent sterilization and eliminates the risk of local myometrial invasion as a cause of persistent mole. Due to the possibility of metastasis even after hysterectomy, the risk of post-molar gestational trophoblastic disease still remains between 3% and 5%, thus requiring long-term follow-up of hCG.19 Drug induction and hysterotomy are not recommended for termination of molar pregnancy. These methods increase maternal morbidity, such as excessive blood loss, incomplete evacuation requiring curettage and the need for cesarean delivery in subsequent pregnancies.

Prophylactic chemotherapy during or immediately after evacuation of molar pregnancy is associated with a reduction in the incidence of persistent mole from approximately 20% to 3%. Chemotherapy is recommended in high-risk patients (age>40 years, hCG>100,000 mIU/mL, uterine enlargement, theca luteal cysts >6 cm, medical complications) and/or when adequate hCG monitoring is not possible.20

After termination of molar pregnancy, follow-up is essential for the detection of trophoblastic disease (invasive mole or choriocarcinoma), which develops in approximately 15% to 20% of patients with a complete mole and 1% to 5% in a partial mole. Clinically uterine involution, regression of theca-lutein cysts and cessation of vaginal bleeding are good prognostic signs. In addition, final follow-up requires serial measurements of serum hCG every 1 to 2 weeks, until three consecutive tests establish normal hCG levels. hCG monitoring should be determined at 3-month intervals for 6 months after documented negative values. Contraception is recommended during the follow-up period of 6 months after the first normal hCG result. Oral contraceptives are preferred because they have the advantage of suppressing endogenous luteinizing hormone (LH), which may interfere with the measurement of hCG at low levels. Indications for treatment of post-molar disease are: plateau of hCG levels within testing every week for 3 weeks, increase in hCG levels ≥10% with weekly measurement for 2 weeks, persistently elevated hCG levels 6 months after evacuation, histopathological diagnosis of choriocarcinoma or trophoblastic tumor or evidence of metastasis. In all subsequent pregnancies, pathological examination of the placenta or other products of conception is recommended, as well as monitoring of the hCG level 6 weeks after birth.21

Partial molar pregnancy is a kind of pathologic pregnancy with bad prognosis in most of the cases, mainly depending on the fetal kariotype. In cases with trisomy, it is recommended to terminate the pregnancy. Vacuum curettage is the preferred method for evacuating molar pregnancy regardless of uterine size in patients who wish to maintain fertility. Hysterectomy is an alternative in patients who do not wish to maintain fertility or are at increased risk of developing postmolar gestational trophoblastic disease. Clinical involution of the uterus, regression of theca-lutein cysts and cessation of vaginal bleeding are good prognostic signs of recovery. Final follow-up requires serial measurements of serum hCG every 1 to 2 weeks, while three consecutive tests show normal hCG levels.

None.

The authors declare there are conflicts of interest.

None.

©2020 Kovachev, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.