MOJ

eISSN: 2471-139X

Introduction: The knowledge of different anatomical variations of the terminal branches of the thoraco-acromial artery is inseparable from any integumentary surgery of the anterior region of the shoulder. It is especially the case when performing surgery of reconstruction flaps of this region, whose use is increasing in recent years. The purpose of our work was to report the modalities of birth and terminal division of the thoracoacromial artery.

Material and methods: We performed a direct and selective injection of 24 thoracoacromial arteries on cadavers preserved in a low-formalin solution rich in glycerin. The injected solution was made of a mixture of methylene blue and gelatin. Cadaveric dissection was then used to study the location, number, and path of the terminal branches of the thoracoacromial artery.

Results: In the thickness of the cellulo-fatty tissue, the thoracoacromial artery gave at least two and at most four terminal branches: two bulky and constant branches (the deltoid and pectoral branches) and two small and inconstant branches (the acromial and clavicular branches). However, anatomical variations were also found in the path and localization of each terminal branch: thus the deltoid and pectoral branches had a vertical downward or oblique path.

Conclusion: The anatomical variations observed on the terminal branches of the thoracoacromial artery can compromise any surgery of the anterior shoulder area of the integument. These variations should be better known by surgeons.

Keywords: thoracoacromial artery, terminal branches, anatomical variations, integuments

The thoracoacromial artery (TAA) is the main integumentary artery of the anterior deltoid region. It supplies part of the antero-cranial wall of the thorax.1,2 This region has been used for many years as a donor site for reconstructions of the neck and head, because it is close to the cervicofacial areas in terms of color, texture and thickness.3,4 However, the thoracoacromial artery can be subject to anatomical variations, both regarding its birth mode than its terminal branching.4

These anatomical variations can have important clinical implications, so they must be taken into account by the practitioner during any regional surgery in general, and particularly during flaps harvesting. The authors of the present article propose to study the anatomical variations interesting as well the trunk of origin than terminal branches of the thoraco-acromial artery.

Surgical anatomy

The TAA arises under the junction between the middle and lateral thirds of the clavicle. It is a large vessel located on the anterior side of the axillary artery; its origin is hidden by the cranial margin of the pectoralis minor muscle.5–7

It gives off two large branches-deltoid and pectoral-that are always present. It also gives off two other variable branches: a clavicular branch that arises directly from the thoracoacromial artery and an acromial branch that-when present-arises directly from the deltoid branch.5–7 These branches, accompanied by their satellite veins, arise from the TAA immediately below the clavicle; they then penetrate the pectoralis major muscle through its underside immediately below the midpoint of the clavicle. The veins are satellites of the arteries.

The clavicular part of the pectoralis major is irrigated medially by the clavicular branch and laterally by the deltoid and acromial branches.5,7 The latter two branches give off musculocutaneous perforators that vascularize the integuments located in the cranial portion of the pectoral wall. The deltoid branch often gives off the acromial branch directly; the latter also provides a musculoskeletal perforator towards the integuments covering the deltoid muscle and the lateral end of the clavicle.5,7

The pectoral branch irrigates the sternocostal part of the pectoralis major muscle.5,7 It quickly gives off three branches: a lateral branch that courses towards the lateral thoracic artery, and two medial and caudal branches directed towards the 4th intercostal space that anastomose with the anterior intercostal arteries and the perforators of the internal mammary artery (IMA).5,78

Although several anatomical variations have been described, the pectoral branch generally courses along a line joining the acromion with the xiphoid process.4 Several musculocutaneous perforators arise from this pectoral branch; however they are generally considered too small to be useful surgically.5 Injections have shown the cutaneous vascular territory of the pectoral branch extends transversely from the nipple to the axillary fossa, beyond the lateral margin of the pectoralis major muscle.7

The deltoid branch crosses the upper part of the delto-pectoral furrow and generally divides into two branches, one deep and the other superficial.1,2 The deep branch runs in the furrow itself, inside a small canal formed by the duplication of the fascia. Arriving at the lower end of the intermuscular space, this deep branch perforates the superficial sheet of the fascial canal in which it is located. It thus arrives inside the subcutaneous plane and branches rapidly into the skin that covers the tendon of the pectoralis major and the distal insertion of the deltoid.1,2

The superficial branch (which represents the acromial branch proper) runs obliquely downwards and laterally; its size is sometimes large and its length can reach 12cm.1,2 It ends at the lateral part of the deltoid region. Along its course, it gives on both sides of its trunk a series of small branches that quickly end in the skin. This acromial branch presents numerous variations: it can be short of 2 to 3cm, or very long and reach the posterior face of the deltoid region; it remains deep in 25% of cases and then perforates the deltoid at a greater or less distance from its anterior edge.1,2

Dissection was performed in 24 anatomical regions from 12 non-formalin fixed cadavers. The mean age was 69 years (range 47-88); there were 9 males and 3 females. The cadavers had no history of surgery or deformity in the areas targeted for dissection (supraclavicular, pectoral and deltoid regions). They were embalmed using a glycerin-rich, formalin-free solution to preserve tissue suppleness.

For the first phase, the cadaver was placed in dorsal decubitus and the posterior triangle was approached to remove the clavicle. The subclavian artery and its collateral arteries were dissected, identified and marked (Figure 1). The dissection was extended to expose the origin of the TAA on the anterior side of the initial portion of the axillary artery. The TAA was injected with a mixture of gelatin, methylene blue and iron powder (Figure 2). The cadaver was then refrozen for 24hours.

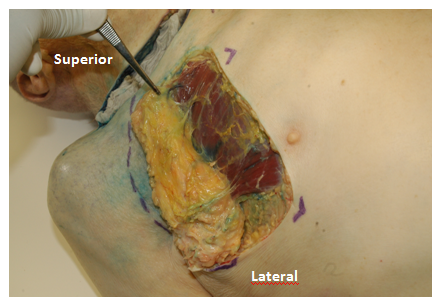

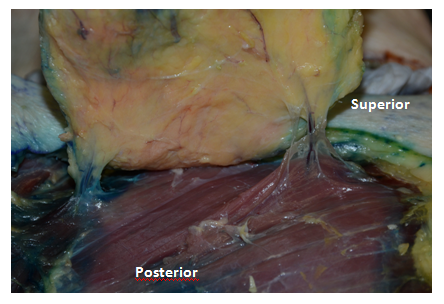

In the second phase, the cadaver was thawed out at room temperature and then placed in dorsal decubitus to dissect the integuments. For this dissection, a superficial incision was made on the lateral, caudal and cranial margins of the cutaneous perforasome, making sure not to breach the muscle layer. Next, the superficial plane was separated from the muscle layer from the periphery to the center of each perforasome (Figure 3), (Figure 4). This dissection was performed meticulously so as to prevent damaging the satellite veins accompanying each perforating artery. During this procedure, the perforators were dissected and inventoried based on their location, dimensions, orientation, frequency and size of the cutaneous perforasome. Dissection of the largest perforators was then continued through the muscle while preserving the integrity of the pectoralis major muscle. The superficial layer (perforator flap) was then harvested completely with its pedicle.

Figure 3 Dissection of the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery and its perforator branches. Specimen number 13 (Table 1).

Figure 4 Dissection of the deltoid branch of the thoracoacromial artery and its perforator branches. Specimen number 13 (Table 1).

The average diameter of the TAA was 2.0mm. An average of 3 terminal branches were found on the thoracoacromial artery. The deltoid branch was present in all subjects, the average length of its pedicle was 7 cm, the average diameter of the deltoid perforators was 0.92mm. The pectoral branch was also present in all subjects, the average pedicle length was 7.83cm, and the average perforator diameter was 0.92mm. The acromial branch was absent in 13 subjects out of 24, when it was present the average length of its pedicle was 4.5cm. The clavicular branch was absent in 9 subjects out of 24, when it was present the average length of its pedicle was 4.5cm. No significant differences by sex were noted concerning configuration or size. More detailed findings are given in Table 1.

In the work of Hamel et al.,9 the thoraco-acromial artery was constantly a branch of the first portion of the axillary artery. Its origin was localized on the cranio-medial edge of the pectoralis minor muscle. After a short path, the thoracoacromial artery was divided into 2 branches: a thoracic medial branch and an acromial lateral branch. The acromial branch was moving up and out, passing over the coracoid process. This acromial branch did not branch on the anterior side of the coracoid process, but gave a branch at the coracoid insertion of the coracoacromial ligament. This collateral branch of the acromial branch of the thoracoacromial artery passed under the coracoacromial ligament and irrigated the horizontal portion of the coracoid process. In our work we find as Hamel et al.,9 an origin of the thoracoacromial artery frequently hidden behind the cranial edge of the pectoralis minor muscle.

Four terminal branches are traditionally described in the thoracoacromial artery, however the deltoid and pectoral branches are the largest, with a clavicular branch of variable origin, and an acromial branch which is most often born of the deltoid branch. This assertion of Hallock6 is true in our work.

The precise origin of the thoracoacromial artery is nevertheless a point to be clarified for other authors. According to Loukas et al.10 the thoracoacromial artery originates from the second portion of the axillary artery. However DeGaris et al.11 noted that in most of their dissections the thoracoacromial artery originates from the first portion of the axillary artery. Our dissections showed that it could invariably originate from the middle third or the lateral third of the clavicle.

In the study by Huelke,12 the thoraco-acromial artery was a branch of the second portion of the axillary artery in 2/3 of the cases, and it originated medially to the tendon of the pectoralis minor muscle in 1/3 cases. The thoracoacromial artery is usually located next to the medial border of the pectoralis minor muscle, rather than directly behind the muscle or facing its lateral edge. Other origins are rare. In one case the thoracoacromial artery even originated from the brachial artery. These findings concerning the origin of the thoracoacromial artery do not agree with the results of DeGaris et al.11 DeGaris reports that the thoracoacromial artery is more frequently born from the first (86%) and the second portions (12%) of the axillary artery. The division of the axillary artery into 3 portions is borrowed from Huelke.12 The first portion is located within the medial border of the small pectoralis muscle, the second portion is located behind the muscle and the third portion laterally at the lateral edge of the same muscle.

Park et al.,13 reported that the origin of the thoracoacromial artery at the level of the axillary artery was located laterally to the mid-clavicular line in the dissections on the right side. This point was medially located in relation to the mid-clavicular line in the dissections on the left side. This correlation to the mid-clavicular line according to the left or right side was not studied in our work. The study by Park et al.13 also shows that the thoracoacromial artery arises truncularly from the axillary artery and then laterally moves 2-3cm below the clavicle, before rapidly giving rise to several terminal branches.

Although most authors agree that the thoracoacromial artery invariably arises as a direct and isolated branch of the axillary artery, the literature reports numerous anatomical variations in both the collateral branching of the axillary artery and in that of the thoraco-acromial artery.7,14 These variations have been studied by Trotter et al.,15 during the dissection of axillary arteries of 384 arms. From their work it appears that the supreme thoracic and thoracoacromial arteries arise from the axillary artery in almost all the dissected specimens. However, in 4 dissections (1%), the supreme thoracic artery originated from the thoracoacromial artery, and on a dissected specimen the thoracoacromial trunk was absent and its terminal branches thus arose directly from the axillary artery.

Anatomical variations also appear in the anatomical relations of the thoracoacromial and lateral thoracic arteries, and in particular with regard to their mode of birth. Many anatomy books stipulate that the lateral thoracic artery is most often born from the axillary artery at the level of its middle part; it may be infrequent in the first or third of the axillary artery.16 However the recent work of Loukas et al.,17 (series of 840 cases) found different tendencies with a predominance of the origin of the thoracic lateral artery at the level of the thoraco-acromial artery (67.7%). Only 17.2% of the thoracic lateral arteries originate in the axillary artery. Lee et al.,16 also compiled data about collateral branches of the axillary artery. They report that in 69.2% of cases the lateral thoracic artery arises from the axillary artery. It emerges from the thoracoacromial artery in only 2.6% of cases. Huelke12 reports a similar trend (6.7%). Apart from the work of DeGaris et al.11 those of Pandey et al.18 and those of Loukas et al.,17 most studies show that the origin of the lateral thoracic artery in the thoracoacromial artery is rather rare. The results of Lee et al.16 are consistent with Korean work by Kang et al.,19 and with the Japanese works of Adachi et al.,20 though much older. All this suggests that there are probably variations of racial origin. For Paraskevas et al.,21 the incidence of the origin of the lateral thoracic artery on the thoracoacromial artery cited in the work of DeGaris et al.11 is not 43% as reported by Huelke12 & Loukas.18 This incidence is actually 73% in Caucasians and 52% in Black Americans. Pellegrini et al.,22 report when to them a frequency of 14%. According to Paraskevas et al.,21 the literature reports in addition to the racial differences of the tendencies according to the sex with regard to the configuration of the collateral branches of the axillary artery.

The configuration of the terminal branches of the thoracoacromial artery is also subject to anatomical variations. Our work shows that the thoracoacromial artery has 2 to 4 terminal branches with an average of 3. It contains the 2 constant deltoid and pectoral branches, measuring up to 7 to 8cm long, and whose perforators are the most voluminous in the region (0.92mm on average).

Several authors consider the pectoral branch to be the largest of the terminal branches of the thoracoacromial artery.22 Park et al.13 classified the mode of birth of the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery. The pectoral branch could be directly derived from the thoracoacromial artery (type I: 79%). It could also arise from the thoracoacromial artery via a medial pedicle (type II) or a lateral pedicle (type III). These variations may have major clinical implications, since from an anatomical point of view, the arterial distribution of the pectoralis major muscle is supplied by the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery, the lateral thoracic artery and the anterior intercostal arteries. Park et al.,13 also documented variations on the other terminal branches of the thoracoacromial artery.

Our study shows that the pectoral branche has only a few variations concerning its trajectory and the direction of its perforators. On the contrary, its length can double from one subject to another. Geddes5 also write about the constant nature of this pectoral branch. Indeed, in his work on the perforators of the anterior wall of the thorax, he reports that the pectoral branch of the thoracoacromial artery is inconstant, and that it presents only tiny muscular-cutaneous perforators in the infero-lateral and middle zones of the pectoralis major muscle. This variation would have clinical repercussions, since it would make the probability of producing a pedicled perforating flap on this pectoral branch weak, as opposed to the flaps exploiting the deltoid and clavicular branches of the thoracoacromial artery. Moreover, according to the work of Geddes,5 despite the fact that the arterial territories vary significantly, the path of the different terminal branches of the thoracoacromial artery as well as that of their perforators is more constant, both integumentary than muscular. In our work, this regularity of the path appears essentially for the deltoid and pectoral branches.

Indeed, our study shows that the deltoid branch also appears to be relatively variable, except for the birth of the acromial artery, which is absent in 13 cases out of 24. Hallock6 also reports this constant character of the deltoid branch of the thoracoacromial artery. In his work, the deltoid branch irrigates the clavicular insertion of the pectoralis major muscle. It often gives an acromial branch which supplies a musculocutaneous perforator towards the integuments covering the deltoid muscle and the lateral extremity of the clavicle. This pectoral branch divides rapidly to irrigate the sternocostal portion of the pectoralis major muscle.

Our work also reports the existence of 2 inconstant acromial and clavicular branches. These inconstant branches are shorter (4.5 cm on average) and have smaller perforators than those of the deltoid and pectoral branches. When present, they are much more subject to anatomical variations than the pectoral and deltoid branches. These variations concern their dimensions as well as their path. However, our work did not show any variations according to the sex of the subjects.

In addition to the 4 "classic" terminal branches of the thoraco-acromial artery, the literature is already inconsistently reporting the existence of additional terminal branches. These include the lateral thoracic and supreme thoracic arteries. Lee23 & Loukas17 reported the existence of a radial artery directly from the thoracoacromial artery. This anatomical variation can be explained by embryological factors, it can have important clinical implications.

In surgical practice, the treatment of certain lesions of the regions of the head and neck sometimes requires large resections, thus requiring the realization of reconstruction flaps. The condition for achieving these flaps is a good arterial perfusion of the tissue removed. It is therefore essential to have a precise knowledge of the vascularization of the regions concerned and possible anatomical variations.

Beside the classical description of the origin and termination of the thoracoacromial artery, there are atypical aspects so the practitioner must take into account before any surgery involving this artery or one of its branches. Although in our work most of the variations concern the configuration of the terminal branches, several authors document particular cases showing an axillary origin of the thoracoacromial artery.

None.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this study.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.