Journal of

eISSN: 2475-5540

Review Article Volume 10 Issue 1

Department of Bioengineering, University of California, USA

Correspondence: Dr. Bill Tawil, Department of Bioengineering, UCLA School of Engineering, 420 Westwood Plaza, Room, 5121, Engineering V. P.O. Box: 951600, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1600, USA

Received: July 10, 2025 | Published: August 21, 2025

Citation: Jigisha H, Bill T. A review on vascularized breast reconstruction. J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;10(1):205-215. DOI: 10.15406/jsrt.2025.10.00207

Breast reconstruction after mastectomy is an essential part of modern cancer care, as it helps restore not only a patient’s physical appearance but also their emotional and psychological well-being. In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on achieving better aesthetic outcomes and long-term functionality, rather than simply replacing lost tissue. One of the most promising approaches in this area is vascularized breast reconstruction, which focuses on using well-perfused tissue to reduce complications such as fat necrosis, delayed healing, and tissue loss due to ischemia. This method improves overall graft survival and contributes to more natural-looking results.

This paper explores the current state of vascularized breast reconstruction by examining both the surgical techniques being used and the new technologies being developed to support them. It highlights major advancements in autologous flap procedures like the DIEP (Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator), SIEA (Superficial Inferior Epigastric Artery), and PAP (Profunda Artery Perforator) flaps, which are becoming more common because they allow for better blood flow and less donor site damage. The role of microsurgery in improving the precision and safety of these procedures is also discussed, including the growing use of surgical planning tools like 3D imaging and preoperative CT angiography.

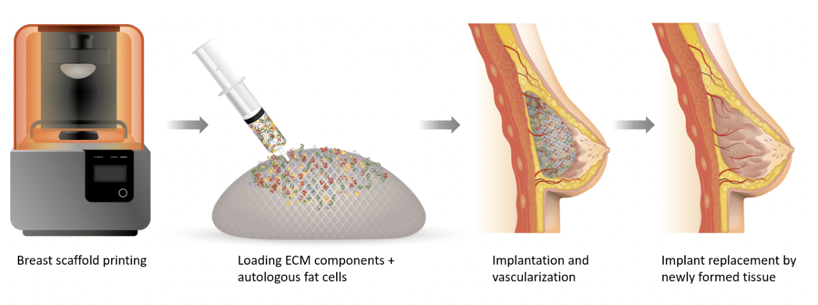

In addition to surgical innovation, the paper looks into the future of reconstruction through tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Technologies like 3D bioprinting, resorbable scaffolds, and stem-cell-based therapies are being developed to better mimic the body’s natural healing processes and encourage new blood vessel growth. These tools not only offer new possibilities for reconstruction but also address some of the limitations of traditional methods, such as implant rejection or lack of long-term durability.

Lastly, this paper examines the current trends in the breast reconstruction market, pointing out which solutions are gaining popularity, what gaps still exist in patient care, and how clinical needs are driving innovation. Overall, this review aims to give a comprehensive overview of how vascularized breast reconstruction is evolving and why it is becoming central to postmastectomy treatment.

Keywords: breast reconstruction, mastectomy, vascularized reconstruction, autologous flap, microsurgery, tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, 3D bioprinting, stem-cell therapy, resorbable scaffolds, CT angiography, implant rejection, surgical planning, accessibility

DIEP, deep inferior epigastric perforator; SIEA, superficial inferior epigastric artery; PAP, profunda artery perforator; TDLUs, terminal duct lobular units; CT, computed tomography; 3D, three-dimensional; ECM, extracellular matrix; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; CAGR, compound annual growth rate; ASCs, ambulatory surgical centers; ADMs, acellular dermal matrices; TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous; ADRCs, adipose-derived regenerative cells; VLNT, vascularized lymph node transfer; NAC, nipple-areolar complex

Breast reconstruction, especially vascularized breast and mammary gland reconstruction, is a highly technical but deeply meaningful branch of reconstructive surgery.1 It is primarily aimed at individuals recovering from mastectomy due to breast cancer, which remains the leading primary indication.2 Secondary conditions include congenital breast abnormalities like Poland syndrome, severe trauma, and complications from previous surgeries.3 The goal isn’t just cosmetic; it’s about restoring both the natural shape and feel of the breast using living tissue with its own blood supply.2 This is what sets vascularized autologous reconstruction apart. Common surgical techniques include the DIEP (Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator) flap, which harvests fat and skin from the lower abdomen while preserving muscle, and the Latissimus Dorsi flap, which uses muscle and tissue from the upper back. These methods create a more natural aesthetic and tactile result than silicone implants, although they come with higher costs, longer recovery times, and require microsurgical expertise.4

One major challenge is accessibility. These procedures are expensive, and insurance coverage varies drastically depending on location and provider. Patients in rural or underserved areas are often left behind due to poor reimbursement frameworks and lack of specialized centers. Despite that, the field is rapidly evolving.5 Clinical trials are now exploring stem cell-based regeneration, 3D bioprinting of breast tissue, and lab-grown vascularized grafts to improve integration, reduce complications, and offer options to those who can’t undergo traditional flap surgeries.4 Advanced imaging and pre-surgical 3D modeling have also revolutionized planning, giving surgeons precise blueprints for reconstruction. While we are not fully there yet in terms of making this care universally accessible, the direction is promising. Technology, research, and increasing patient awareness are reshaping the future of breast reconstruction.6

Healthy breast tissue in humans is a complex, dynamic, and hormonally responsive organ system that comprises multiple integrated tissue types, including epithelial, stromal, adipose, vascular, lymphatic, and immune components. Each of these elements plays a vital role in maintaining the structural integrity, functional capacity, and regenerative potential of the breast. A comprehensive understanding of healthy breast tissue architecture is essential for both diagnostic assessment and reconstructive interventions.7

At the histological level, the breast is organized into 15–20 lobes, each consisting of smaller lobules called terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs), the functional and developmental units of the breast. These TDLUs are composed of alveoli (milk-producing glands) and a branching ductal system. The epithelial layer within these units contains polarized luminal epithelial cells responsible for secretory function, supported by an underlying layer of contractile myoepithelial cells, which facilitate milk ejection. Both layers rest on a continuous basement membrane, which maintains cell polarity, regulates permeability, and acts as a barrier against invasive pathologies. The proper organization and differentiation of these epithelial cells, without signs of cellular atypia, dysplasia, or abnormal mitotic activity, are hallmarks of healthy tissue.8

Surrounding the epithelial units is the stromal microenvironment, comprising fibroblasts, immune cells, and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. The ECM includes collagen types I and III, laminin, elastin, fibronectin, and various glycosaminoglycans that provide both mechanical support and bioactive signaling. In healthy tissue, fibroblasts regulate ECM remodeling in a controlled manner, and there is no evidence of desmoplastic reaction or fibrosis. The stroma also modulates epithelial-stromal interactions, which are critical for development, maintenance, and response to hormonal changes.8

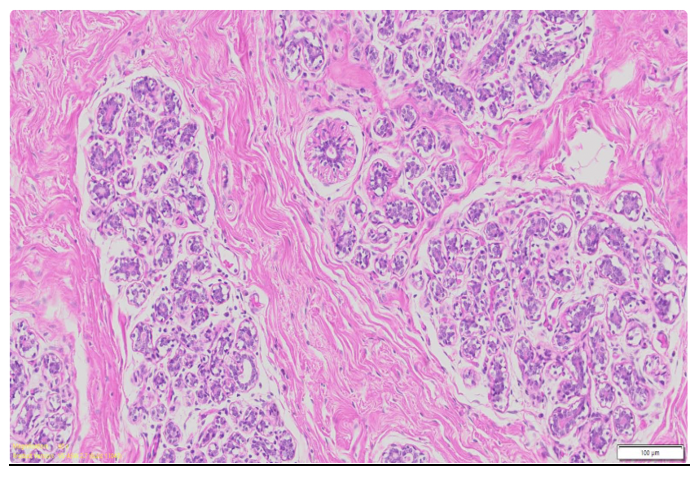

A significant portion of the breast is made up of adipose tissue (Figure 1), especially in post-adolescent, non-lactating females.9 Adipocytes not only determine breast volume and contour but also serve endocrine functions, producing adipokines (e.g., leptin, adiponectin, resistin) and cytokines that influence local immune responses and hormonal signaling. In healthy tissue, adipose deposits are well-vascularized, without necrosis, inflammation, or fibrosis. Their presence also contributes to the elasticity and pliability of the breast, factors critical for surgical manipulation and reconstructive applications.10

Figure 1 Microscopic cross section of the mammary tissue.33

This image shows the histological architecture of mammary tissue, highlighting ducts, adipose tissue, and connective stroma.

Vascularisation in healthy breast tissue is robust and well-distributed. The arterial supply comes primarily from branches of the internal mammary artery, lateral thoracic artery, and thoracoacromial artery, forming a dense capillary network that supports epithelial, stromal, and adipose compartments. Adequate venous drainage via the superficial and deep venous systems is essential for maintaining interstitial fluid balance and oxygenation. Importantly, this vascular infrastructure is crucial for procedures such as vascularised flap reconstruction, where microsurgical anastomosis relies on the integrity of these vessels.11

The lymphatic system in healthy breast tissue plays a critical role in immune surveillance and fluid homeostasis. Lymphatic drainage primarily flows toward the axillary, parasternal, and supraclavicular nodes. There is no evidence of lymphatic obstruction, inflammation, or dilation in healthy tissue. The immune environment includes resident macrophages, T cells, and dendritic cells which, under normal circumstances, remain in a state of tolerance and do not display excessive cytokine activity or infiltration.12

On the hormonal front, healthy breast tissue exhibits cyclic changes in response to endogenous estrogens, progesterone, prolactin, and growth hormone.13 During the menstrual cycle, for example, there is mild epithelial proliferation and stromal edema during the luteal phase, followed by regression in the follicular phase. These changes are regulated and reversible, without signs of abnormal growth or persistence of mitotic activity.14 In pregnancy and lactation, further changes occur in glandular density and epithelial function, which should resolve postpartum in healthy tissue. Importantly, hormone receptors (ER, PR, HER2) in healthy tissue are expressed in balanced levels and do not exhibit overexpression associated with malignancy.15

From a clinical standpoint, healthy breast tissue is typically soft, symmetrical, and non-tender on palpation, with no discrete masses, skin changes, nipple retraction, or discharge. Upon imaging, such as mammography or ultrasound, healthy breast tissue appears with a predictable pattern of fibroglandular density, consistent with the patient’s age, hormonal status, and body composition. There should be no architectural distortion, suspicious microcalcifications, or abnormal lymph nodes.16

In surgical contexts, such as vascularized breast reconstruction, healthy tissue provides the ideal physiological environment for grafting and healing. The preserved vasculature ensures flap perfusion, while pliable and elastic dermal and subcutaneous layers allow for more natural shaping and better cosmetic results. The absence of prior radiation, fibrosis, or infection minimizes the risk of complications such as necrosis, dehiscence, or delayed wound healing. Moreover, in patients undergoing prophylactic mastectomies (e.g., BRCA1/2 mutation carriers), the presence of healthy, non-diseased tissue dramatically improves both short-term surgical outcomes and long-term reconstructive success.17

Diseased breast tissue, particularly in the context of breast cancer and its treatments, undergoes significant pathological and physiological changes that pose major challenges to vascularised breast reconstruction. Unlike healthy tissue, which is structurally organized, well-perfused, and hormonally regulated, diseased tissue is often fibrotic, inflamed, and poorly vascularised, creating a biologically hostile environment for surgical intervention.18

In diseased breast tissue, normal architecture is lost. The terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs), which are the basic functional units of the breast, are frequently replaced or infiltrated by malignant cells. These cancerous cells exhibit features such as loss of cellular polarity, nuclear atypia, high mitotic index, and invasion through the basement membrane, leading to the breakdown of structural integrity.18

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), and lobular carcinomas are common forms of pathology seen in diseased tissue. These malignancies not only distort the glandular architecture but also promote local tissue remodeling, angiogenesis, and immune dysregulation. Inflammatory breast cancer, although rare, is another form where diffuse infiltration and lymphatic blockage lead to rapid tissue degeneration.19

One of the most defining features of diseased breast tissue, especially post-treatment, is fibrosis. Radiation therapy and surgical scarring lead to the excessive deposition of collagen I, tenascin-C, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).20 This results in a stiff, inelastic tissue environment. Fibrotic stroma not only reduces the mechanical flexibility needed for surgical manipulation but also hinders neovascularization, crucial for the integration of vascularized flaps.21

This fibrotic state is often reactive and chronic, forming part of a larger desmoplastic response, where stromal fibroblasts (particularly cancer-associated fibroblasts, or CAFs) perpetuate matrix remodeling and contribute to tumor progression and poor reconstructive outcomes.22

Vascular integrity is heavily compromised in diseased tissue. Tumors induce abnormal angiogenesis, forming vessels that are tortuous, leaky, and poorly functional. Radiation further damages endothelial cells, resulting in capillary rarefaction, thrombosis, and vascular occlusion. As a result, the tissue becomes hypoxic, which not only accelerates tumor aggression but also impairs wound healing and increases the risk of flap necrosis.23

The poor perfusion also affects nutrient and oxygen delivery post-reconstruction, making microsurgical procedures significantly more complex. Surgeons are often forced to identify and utilize distant, less-damaged recipient vessels or opt for delayed reconstruction to allow partial tissue recovery.

Diseased breast tissue exhibits a chronically inflamed microenvironment. This includes elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α), macrophage infiltration, and activation of immune checkpoint pathways.24 In the context of cancer, this inflammatory state often shifts toward a tumor-promoting phenotype, where immune cells fail to recognize or destroy cancerous cells and instead contribute to ECM degradation, angiogenesis, and local immunosuppression. Post-radiation, this inflammatory environment persists and further drives tissue damage through oxidative stress, delayed fibroblast function, and increased fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition. All these factors contribute to delayed healing, higher infection rates, and postoperative complications in reconstructive surgery.25

Breast cancer often arises from cells that are hormone receptor-positive (e.g., ER+, PR+), where hormone signaling pathways become dysregulated. This leads to estrogen-driven proliferation and cellular resistance to normal apoptotic signals. In more aggressive forms like triple-negative breast cancer, the absence of hormone receptor expression corresponds with poorly differentiated, highly proliferative cells that invade surrounding tissues more aggressively and respond poorly to conventional therapies. Even in patients’ not currently undergoing treatment, prior hormonal therapies (e.g., tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors) can induce long-term changes in breast tissue density, vascularity, and responsiveness, affecting reconstructive planning and outcomes.26

The presence of diseased tissue significantly alters the surgical landscape. Post-cancer tissue is often inhospitable for reconstruction due to its stiffness, reduced blood supply, and vulnerability to breakdown. Patients who have undergone radiation have a markedly higher rate of flap complications, including partial necrosis, fat necrosis, seroma, and infection.

Moreover, multiple previous surgeries, biopsies, or lumpectomies can lead to adhesions, anatomical distortion, and scar formation, making it difficult to plan and execute reconstructions that are both functional and cosmetically acceptable. Surgeons may need to employ preconditioning techniques like hyperbaric oxygen therapy or consider free flap procedures with recipient vessels outside the irradiated zone.27

Diseased breast tissue, whether due to malignancy, radiation, or chronic inflammation, presents a biologically and structurally compromised environment. The combined effects of fibrosis, vascular insufficiency, hormonal dysregulation, and immune disruption pose significant obstacles to successful vascularized breast reconstruction. Unlike healthy tissue, which supports healing and integration of grafts, diseased tissue requires tailored surgical strategies, rigorous patient selection, and often, multidisciplinary management to mitigate complications and achieve optimal outcomes.24

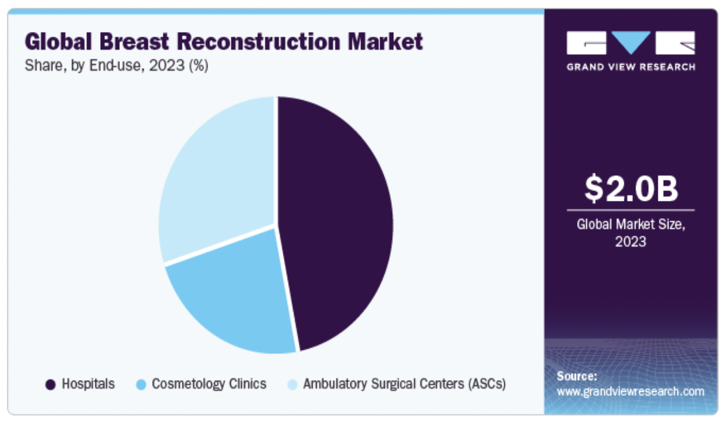

The global breast reconstruction market was valued at approximately USD 2.0 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.54% from 2024 to 2030 (Figure 2). This growth is driven by several factors, including the increasing incidence of breast cancer, favorable reimbursement policies, and advancements in surgical techniques.

Figure 2 Global breast reconstruction market.28

A graphical overview of the global market size and projected growth trends for breast reconstruction procedures.

The breast reconstruction market in the United States is well-established with high adoption rates of implant-based and autologous reconstruction techniques. Growth in this mature market is steady but slower compared to emerging regions. In contrast, emerging markets such as Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and parts of Europe are experiencing faster growth due to increasing breast cancer incidence, expanding healthcare infrastructure, and rising awareness about reconstructive options. These regions present significant opportunities for innovative vascularized and regenerative reconstruction technologies, which aim to improve long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction². Industry players are actively pursuing clinical trials, awareness initiatives, and tailored product launches to meet the unique demands of these growing markets.28

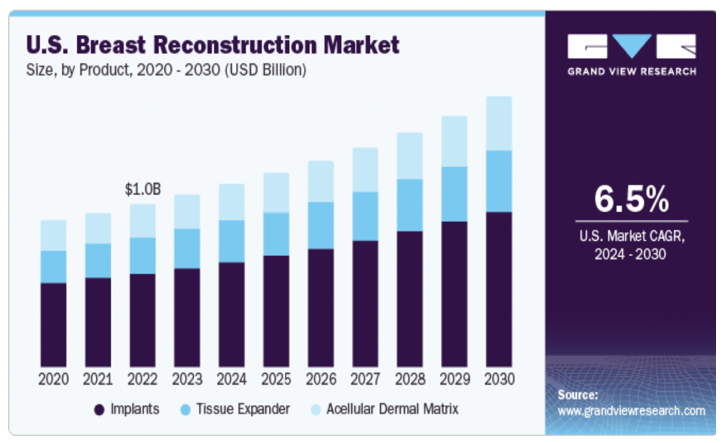

Favorable reimbursement policies, such as Medicare coverage for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction and Australia's external breast prosthesis reimbursement program, are encouraging more patients to opt for reconstruction procedures. Additionally, technological developments and a rise in the number of breast reconstruction procedures are anticipated to further drive market expansion (Figure 3).28

Figure 3 United States breast reconstruction market.28

Market data specific to the U.S., including procedure volume and financial projections.

Hospitals accounted for the largest share of the market in 2023, with a 46.79% share, due to the increasing number of hospitals worldwide and the rise in medical tourism. Ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) are projected to witness the fastest CAGR of 6.64% from 2024 to 2030, attributed to the growing number of breast reconstruction surgeries performed in these settings.

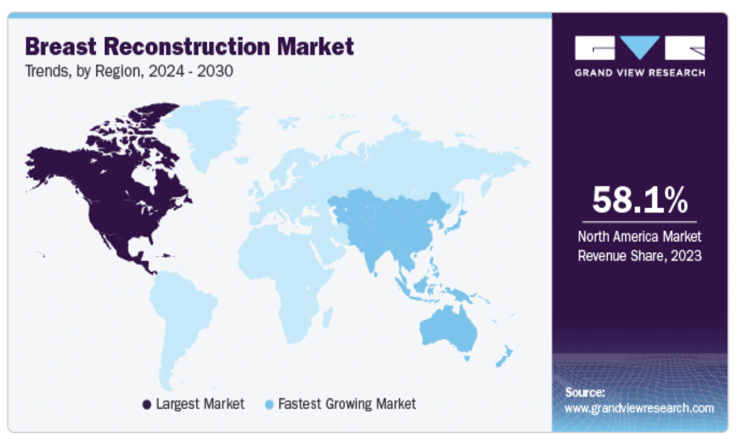

Regionally, North America dominated the market with a 58.09% revenue share in 2023, owing to the rising number of breast cancer cases and well-established healthcare infrastructure. Asia Pacific is projected to register a CAGR of 6.91% from 2024 to 2030 (Figure 2), driven by the rapidly increasing number of breast cancer cases and growing awareness about breast reconstruction surgeries.

Key players in the market are undertaking strategic initiatives such as product launches, awareness campaigns, and geographic expansions to meet the increasing demand for breast reconstruction. For instance, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and The Plastic Surgery Foundation organized the Breast Reconstruction Awareness Day program on October 18, 2023, to create awareness about breast reconstruction among women diagnosed with breast cancer.

The breast reconstruction market is experiencing significant growth due to rising breast cancer cases, supportive reimbursement policies, and technological advancements (Figure 4). With continued efforts in awareness and innovation, the market is poised for sustained expansion in the coming years.28

Figure 4 Trends in the breast reconstruction market.28

Illustrates key industry trends, including shifts in surgical preferences and emerging technologies.

Currently, the breast reconstruction market is dominated by implants and autologous tissue grafts in combination, such as abdominal or thigh-based flaps. While these methods have been refined over the years and remain the standard of care, there is a notable absence of commercially available vascularized tissue-engineered products. However, the field is rapidly evolving, with significant research and development efforts underway to create next-generation solutions that integrate vascularization into engineered constructs. These emerging technologies hold promises for improving functional and aesthetic outcomes while minimizing donor site morbidity.28,29

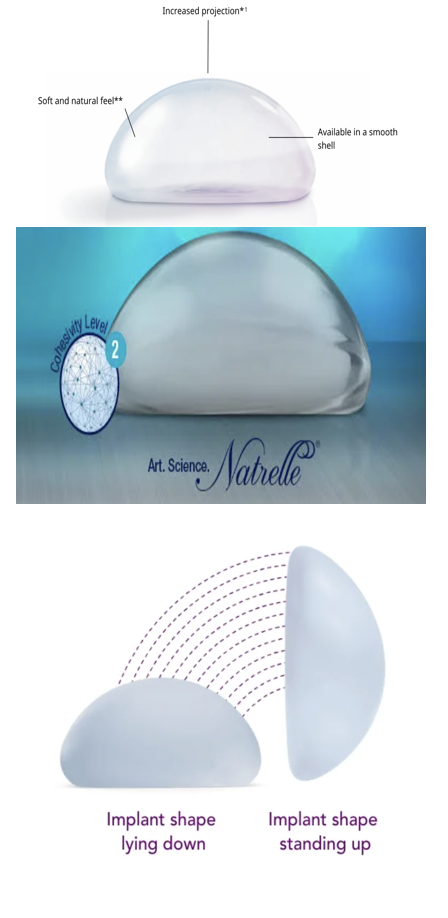

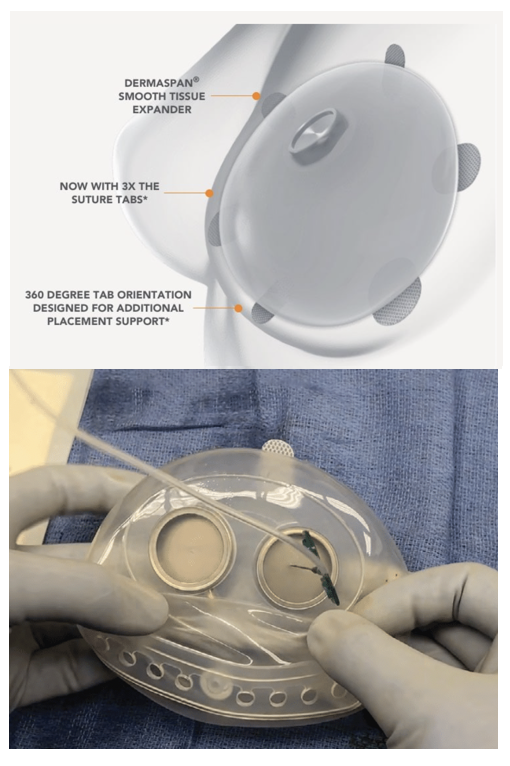

The breast reconstruction market is competitive and diverse, with several companies offering implants tailored to surgical needs and patient preferences. Mentor Worldwide LLC, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, leads with products like MemoryGel™, MemoryShape™, CPX4™ tissue expanders, and the Becker™ expandable implant, praised for their durability and FDA approval (Figure 5A). Mentor's global reach, innovative product development, and focus on surgeon education have further solidified its dominance. In 2024, it gained FDA approval for the MemoryGel™ Enhance Breast Implants, addressing demand for larger reconstructions. Allergan Aesthetics, part of AbbVie, offers Natrelle® silicone and saline implants and tissue expanders, known for clinical safety and efficacy (Figure 5B). It also launched the Reblossom Project in 2023 to promote reconstruction awareness.30,31

Sientra Inc. differentiates itself with AlloX2 Pro™ dual-port tissue expanders and the Vitality™ fat transfer system, which shows over 80% volume retention in clinical studies (Figure 6). Establishment Labs' Motiva® Implants, including SmoothSilk® Ergonomix™, stand out for digital tracking and biocompatibility, with recent FDA clearance expanding their U.S. market presence (Figure 5C).32,33

Figure 5 (A) MemoryGel™ (B) Natrelle® silicone and saline breast implants (C) Motiva® implants, including SmoothSilk® Ergonomix™.30-32

Visual comparison of leading commercial breast implant products based on structure and texture.

Figure 6 Sientra specializes in silicone gel breast implants and tissue expanders, including the AlloX2 Pro™ Tissue Expander with dual-port technology.32

Depicts innovations by Sientra, particularly their advanced tissue expansion systems used in reconstruction.

Integra LifeSciences markets SurgiMend® acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) that reduce risks like capsular contracture and improve tissue coverage.34 BellaSeno GmbH introduces 3D-printed, bioresorbable Senella® scaffolds, aiming to eliminate the need for silicone.35 GC Aesthetics’ FixNip NRI implant enhances nipple reconstruction outcomes.36 Other notable players include POLYTECH Health & Aesthetics (Germany), Sebbin (France), Silimed (Brazil), and HansBiomed (South Korea), offering varied implant types and patient-specific options.37

Breast reconstruction using autologous tissue, particularly for individuals who have previously undergone implant-based reconstruction, offers a more natural and long-term solution. Among the most commonly utilized techniques are abdominal flaps, which include the pedicled TRAM (transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous) flap, the free TRAM flap, the DIEP (deep inferior epigastric artery perforator) flap, and the SIEA (superficial inferior epigastric artery) flap. The pedicled TRAM flap involves the use of skin, fat, and the entire rectus abdominis muscle from the lower abdomen, which remains attached to its original blood supply and is tunneled to the chest. However, this approach often results in a loss of abdominal muscle function and increased postoperative weakness.38

The free TRAM flap refines this method by harvesting only a portion of the rectus muscle and completely detaching the tissue, which is then reconnected to chest blood vessels via microsurgery. The DIEP flap represents an even more advanced technique, preserving the abdominal muscle entirely by isolating and transplanting only the skin, fat, and perforator vessels. This method significantly reduces the risk of abdominal weakness and postoperative complications. Microsurgical equipment such as the Leica Proveo 8 microscope and the Synovis Microvascular Anastomotic Coupler are commonly used to assist with vessel reconnection and improve surgical precision.38-40

The SIEA flap, while similar in its use of lower abdominal tissue, relies on superficial blood vessels that do not traverse the abdominal muscle. Although it offers an even less invasive alternative with quicker recovery, it is limited by the inconsistency and small caliber of these vessels in many patients.41

In cases where abdominal tissue is not available or sufficient, thigh-based flaps provide an alternative. These are particularly suitable for patients with small to medium-volume breasts and can be combined with implants or other flaps for greater volume. The flaps are based on the gracilis muscle in the inner thigh, which is generally nonessential for daily function. Variations in incision orientation include the TUG (transverse), VUG (vertical), and DUG (diagonal) flaps. While these procedures often result in improved thigh contour, they may leave visible scarring depending on incision placement and healing.42

Similarly, gluteal-based flaps such as the SGAP (superior gluteal artery perforator) and IGAP (inferior gluteal artery perforator) flaps offer a muscle-sparing option using skin and fat from the buttocks. These flaps are ideal for patients who cannot use abdominal or thigh tissue or prefer not to use implants. SGAP flaps are typically preferred over IGAP flaps due to scar placement and comfort, as the latter may impact seated positions.43

Recovery from microsurgical tissue transfer, including free TRAM, DIEP, SIEA, SGAP, and IGAP flaps, involves close monitoring of flap viability in a hospital setting. Timely intervention may be required in case of compromised blood flow.

Currently, while there is limited commercial development of vascularized tissue implants, the field is rapidly evolving.44 Implant-based reconstructions dominate the current market, with leading products such as Natrelle by AbbVie, Mentor MemoryGel by Johnson & Johnson, and Motiva by Establishment Labs used in combination with autologous flaps or as standalone solutions (Table 1).

|

Company / Method |

Product / Technique |

Type |

Key features |

|

Mentor Worldwide (J&J) |

MemoryGel™, MemoryShape™, CPX4™, Becker™ expandable implant, MemoryGel™ enhance |

Silicone implants, tissue expanders |

FDA-approved, durable, customizable sizes, global reach |

|

Allergan (AbbVie) |

Natrelle® silicone & saline implants, tissue expanders |

Implants & expanders |

Clinically safe, extensive options, supports Reblossom awareness initiative |

|

Establishment labs |

Motiva® SmoothSilk® Ergonomix™, digital tracking implants |

Silicone implants |

Biocompatible, digital traceability, high global adoption |

|

Sientra |

AlloX2 Pro™ dual-port expanders, viality™ fat transfer system |

Expanders & fat grafting |

80%+ volume retention, innovation in dual-port expanders |

|

Integra lifeSciences |

SurgiMend® acellular dermal matrix (ADM) |

ADM scaffold |

Reduces capsular contracture, enhances soft tissue integration |

|

BellaSeno GmbH |

Senella® 3D-printed bioresorbable scaffolds |

Tissue scaffold |

Silicone-free, customizable shape, bioresorbable |

|

GC aesthetics |

FixNip NRI implant |

Nipple reconstruction implant |

Enhances nipple reconstruction outcomes |

|

POLYTECH health & aesthetics |

Varied implant portfolio |

Implants |

Custom shapes, European standards |

|

Sebbin (France) |

Range of silicone implants |

Implants |

Focused on customization, European presence |

|

Silimed (Brazil) |

Silicone implants |

Implants |

Latin American market focus |

|

HansBiomed (South Korea) |

Implants and tissue expanders |

Implants |

Regional availability, R&D in biomaterials |

|

TRAM Flap (Pedicled) |

Transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap |

Autologous tissue |

Uses full rectus muscle, more muscle loss, higher complication risk |

|

Free TRAM flap |

Microsurgical transfer of partial rectus tissue |

Autologous tissue |

Less muscle removed, improved abdominal function |

|

DIEP flap |

Deep inferior epigastric perforator flap |

Autologous tissue |

Muscle-sparing, high precision, less morbidity |

|

SIEA flap |

Superficial inferior epigastric artery flap |

Autologous tissue |

Minimally invasive, but vessels often inadequate |

|

TUG / VUG / DUG flaps |

Transverse/vertical/diagonal upper gracilis flap |

Thigh-based autologous tissue |

Good for small-medium reconstructions, leaves thigh scar |

|

SGAP / IGAP flaps |

Gluteal artery perforator flaps |

Buttocks-based autologous tissue |

No muscle used, suitable alternative for patients avoiding abdominal tissue |

|

Leica microsystems |

Proveo 8 microscope |

Microsurgery tool |

Enhances precision in vascularized flap microsurgery |

|

Synovis MCA |

Microvascular anastomotic coupler |

Microsurgical device |

Aids in faster and more reliable vessel reconnection |

Table 1 Existing products and treatments comparison table29-44

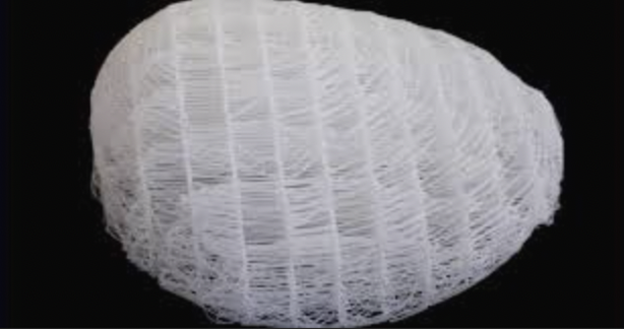

While implants remain a mainstay in breast reconstruction, the field is rapidly shifting toward vascularized and biointegrative techniques that promote natural tissue regeneration, improved aesthetic outcomes, and reduced long-term complications.29 At the forefront of this movement is Tensive Srl, an Italian biomedical firm developing REGENERA (Figure 7), a bioabsorbable scaffold engineered to support natural breast tissue regeneration post-lumpectomy.45 The scaffold gradually degrades as it is replaced by the patient’s own tissue, eliminating the need for permanent implants and minimizing foreign body-related complications.46 REGENERA is currently undergoing multicenter clinical trials in Italy, including at the European Institute of Oncology and Santa Chiara Hospital, to evaluate its efficacy and safety in real-world settings.47

Figure 7 Regenera, a bioabsorbable scaffold by Tensive Srl.45

An image of the Regenera scaffold designed to support natural tissue regeneration post-reconstruction.

Complementing this approach is BellaSeno GmbH, based in Germany, which has created Senella® (Figure 8), a 3D-printed, bioresorbable scaffold designed to support autologous fat grafting.48 Using additive manufacturing, Senella® provides a porous architecture that encourages the infiltration and stabilization of fat tissue harvested from the patient, enabling the growth of vascularized, volume-stable breast tissue.49 The scaffold degrades over time, reducing long-term risks associated with synthetic implants. First-in-human trials began in 2019 in Germany, with ongoing studies focused on long-term outcomes.50

Figure 8 Senella®, a 3D-printed, bioresorbable scaffold by BellaSeno.48

Highlights a customizable, 3D-printed scaffold aimed at promoting adipose tissue integration.

InGeneron Inc. contributes to this regenerative landscape with its Transpose RT System, which isolates adipose-derived regenerative cells (ADRCs) from the patient's own lipoaspirate at the point of care. These cells exhibit pro-angiogenic and tissue regenerative properties, making them valuable for enhancing integration and healing in autologous fat grafts or tissue-engineered constructs. Although the system is not exclusive to breast reconstruction, its applications in regenerative medicine are broad and impactful.51

For procedures requiring vascular integration such as DIEP flap reconstruction, LeMaitre Vascular offers biologic patches and grafts that promote host tissue in-growth and vascularization. These products are often used to reinforce vascular anastomoses and enhance soft tissue regeneration in complex reconstructions. Integra LifeSciences plays a dual role in both implant-based and vascularized reconstruction. Its SurgiMend® Acellular Dermal Matrix (ADM) is derived from fetal bovine dermis and serves as a biologic screconstruction (ular infiltration and neovascularization. It is widely used in autologous flap procedures to support and integrate transplanted tissue, reducing tension and improving outcomes in soft tissue coverage.34

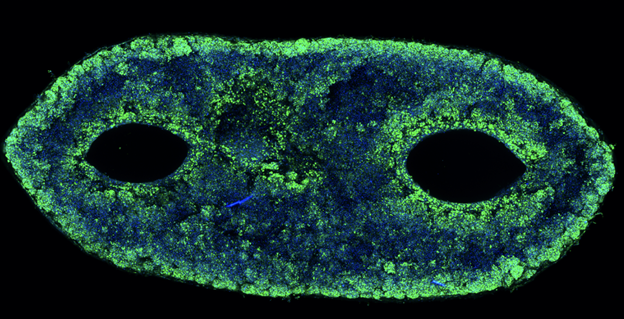

In the space of vascularized breast reconstruction, there are a few exciting pipeline products and clinical trials focused on pushing the boundaries beyond traditional autologous tissue flaps like the DIEP flap.29 One of the most cutting-edge developments is “ReConstruct” by the Wyss Institute at Harvard, which uses bioprinting (specifically, a method called SWIFT: Sacrificial Writing Into Functional Tissue) to create vascularized adipose tissue grafts from the patient’s own cells (Figure 9). These 3D-printed tissues are designed to integrate with the patient’s natural vasculature and mimic the shape and softness of real breasts, offering a potentially safer, more aesthetic alternative to implants. In the U.S., the Wyss Institute at Harvard is pioneering the ReConstruct platform, which utilizes 3D bioprinting to fabricate personalized, vascularized adipose tissue constructs for breast reconstruction. This innovative method integrates endothelial and stromal cells within bioinks to form functional microvascular networks, supporting both tissue viability and integration. The platform seeks to address limitations of fat grafting by improving graft retention and vascularization. The research team is preparing to commercialize this platform through a startup venture, targeting translational application in reconstructive microsurgery.53

Figure 9 Microscopy image of the vascular channels within the adipose tissue bioprinted by Wyss Institute.53 Shows engineered vascular networks critical for sustaining tissue viability in bioprinted implants.

Meanwhile, clinical trials are increasingly focusing on combining breast reconstruction with lymphatic reconstruction to reduce long-term complications like lymphedema.54 For instance, CollPlant Biotechnologies is developing innovative breast implants aimed at regenerating natural breast tissue, offering alternatives to traditional silicone implants and fat grafting (Figure 10). Their approach includes two main products: injectable implants and 3D bioprinted implants. The injectable implants combine CollPlant's recombinant human collagen (rhCollagen) with autologous fat cells and other materials to create a scaffold that supports cell viability and promotes tissue regeneration. This scaffold is designed to gradually degrade and be replaced by newly formed natural breast tissue, eliminating the presence of foreign materials. The 3D bioprinted implants are constructed using rhCollagen, autologous fat cells, and extracellular matrix components. These implants aim to facilitate tissue regeneration and degrade in harmony with the development of natural breast tissue.55

Figure 10 Injectable implants and 3D bioprinted implants by CollPlant Biotechnologies Ltd.55

Displays cutting-edge regenerative solutions combining plant-derived collagen and 3D bioprinting.

In the evolving field of vascularized breast reconstruction, several promising clinical trials are underway that focus not only on aesthetic outcomes but also on improving lymphatic health post-mastectomy.56 One significant example is the trial led by MD Anderson Cancer Center (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03990610), which is evaluating whether prophylactic vascularized lymph node transfer (VLNT) can reduce the incidence of arm swelling, or lymphedema, in breast cancer patients undergoing autologous breast reconstruction. In this procedure, lymph nodes from an unaffected part of the patient’s body are transferred during the reconstruction process to replace those removed during cancer treatment (57). This approach aims to lower the long-term risk of lymphedema, a common and debilitating side effect (57). The trial specifically seeks to determine how many patients develop lymphedema after undergoing this combined surgery, and compares outcomes to historical controls who did not receive VLNT. As of now, the study has enrolled 25 participants, and results are expected in 2026.57

This trial exemplifies a broader shift in reconstructive strategies where surgeons are integrating vascularized tissue solutions for both form and function. The dual focus on aesthetic reconstruction and lymphatic repair shows how future breast reconstructions may be more comprehensive, healing not just physical appearance but also preventing chronic complications. The technique is still investigational but could soon become a standard adjunct to autologous breast reconstruction if long-term results show a clear benefit in reducing lymphedema incidence and complications.57

Another trial compares outcomes of VLNT alone versus VLNT paired with BioBridge® Collagen Matrix to evaluate how well they reduce arm swelling and improve lymphatic drainage.58 In Egypt, Assiut University is running a study (NCT04246034) combining free abdominal flaps and lymph node transfer to evaluate dual outcomes in aesthetics and lymphatic health. Supporting these studies, a systematic review in the Journal of Clinical Medicine analyzed data from over 100 papers and concluded that simultaneous VLNT and autologous breast reconstruction has promising functional and cosmetic benefits, though more rigorous trials are still needed. These clinical and preclinical innovations reflect a growing shift toward more integrated, vascularized, and biologically compatible approaches in breast reconstruction.59

Another notable advancement in the realm of vascularized and regenerative breast reconstruction is the use of decellularized donor nipple-areolar complex (NAC) grafts, currently being studied in a clinical trial sponsored by BioAesthetics. This trial focuses on improving both the aesthetic and functional outcomes of NAC reconstruction by using donor grafts that have been decellularized to reduce immunogenicity while maintaining biological structure.

The primary goal is to assess wound healing after implantation, but the study also evaluates nipple vascularization, dimensions, patient satisfaction, and sensory recovery over a 12-month period. This approach represents a step forward in regenerative reconstruction, as it attempts to reintroduce a biologically derived NAC that may integrate more naturally with host tissue compared to synthetic or tattoo-based methods.60

Secondary metrics being explored include operative time and surgeon preference, as well as whether the decellularized grafts perform better than standard NAC reconstruction techniques in terms of sensitivity and cosmetic results. The trial is still recruiting, with an estimated enrollment of 36 patients and a study completion target of October 2024. If successful, BioAesthetics’ DCLNAC graft could become a commercially viable, vascular-friendly alternative to current NAC reconstruction options, aligning with the larger trend toward bioengineered, patient-integrated breast restoration strategies (Table 2).60

|

Product type |

Example products |

Common materials |

Proposed advantages |

Proposed disadvantages |

General stage |

|

Bioabsorbable scaffold |

REGENERA (Tensive Srl) |

Bioabsorbable polymer scaffold |

Supports natural tissue regeneration, eliminates permanent implants, reduces foreign body risks |

Limited long-term data |

Clinical trials (Italy, multicenter) |

|

3D printed scaffold for fat grafting |

Senella® (BellaSeno GmbH) |

Bioresorbable polymer, 3D-printed porous structure |

Enables vascularized, volume-stable fat tissue growth, supports fat grafting |

Effectiveness dependent on fat graft retention |

First-in-human trials ongoing (since 2019, Germany) |

|

Adipose-derived regenerative cells |

Transpose RT (InGeneron Inc.) |

ADRCs from patient lipoaspirate |

Enhances fat graft integration and healing; point-of-care processing |

Not exclusive to breast reconstruction |

Broad regenerative use; not specific to breast |

|

Biologic patches & grafts |

LeMaitre Vascular |

Biologic tissue patches |

Promotes vascular in-growth and soft tissue regeneration |

Typically used adjunctively, not as standalone solution |

Commercially available |

|

Acellular dermal matrix (ADM) |

SurgiMend® (Integra LifeSciences) |

Fetal bovine dermis |

Biologic scaffolds support autologous flaps, reduces tension, promotes neovascularization |

Animal-derived material; potential immunogenicity |

Widely used in clinical practice |

|

3D Bioprinted adipose tissue grafts |

Reconstruct (Wyss Institute) |

Patient-derived cells, endothelial + stromal cells, bioinks (SWIFT method) |

Personalized vascularized grafts, integrates with natural vasculature, improves retention and softness |

Still in preclinical/commercialization phase |

Research phase, planning startup commercialization |

|

rhCollagen injectable implant |

CollPlant Injectable Implant |

rhCollagen + autologous fat + bioactive materials |

Degradable scaffold, supports natural tissue regeneration, no foreign body |

Limited large-scale human trial data |

Preclinical/early-stage |

|

3D bioprinted breast implant |

CollPlant 3D Bioprinted Implant |

rhCollagen + autologous fat + ECM components |

Promotes tissue regeneration in sync with degradation, avoids permanent foreign materials |

Requires advanced bioprinting infrastructure |

Preclinical/early-stage |

|

Vascularized lymph node transfer (VLNT) |

VLNT with/without BioBridge® |

Autologous lymph nodes, BioBridge® collagen matrix |

Reduces risk of post-mastectomy lymphedema, enhances lymphatic function |

Surgical complexity, investigational technique |

Clinical trials (e.g., MD Anderson; NCT03990610) |

|

Combined aesthetic & lymphatic surgery |

Assiut University Dual-Flap Trial (NCT04246034) |

Free abdominal flap + lymph node transfer |

Dual benefit: form + lymphatic repair |

Limited global data, still under investigation |

Clinical trials (Egypt) |

|

Decellularized NAC grafts |

DCLNAC (BioAesthetics) |

Decellularized donor nipple-areolar complex |

Improved aesthetics + sensory recovery, biologically integrated alternative to tattoos/synthetic NACs |

Immunogenicity risks still under study |

Clinical trial phase (NCT05484934; ends Oct 2024) |

Table 2 Comparison of existing products45-60

Vascularized breast reconstruction represents a pivotal advancement in post-mastectomy care, offering patients improved aesthetic and functional outcomes through the use of autologous tissue and advanced microsurgical techniques.1 As breast cancer incidence continues to rise globally, the need for sophisticated, patient-centered reconstructive solutions is becoming increasingly urgent.61 These procedures not only provide a more natural look and feel but also reduce long-term complications associated with synthetic implants, such as capsular contracture or the need for revision surgeries.62

Emerging technologies, including robotic-assisted microsurgery, 3D bioprinting, and regenerative tissue engineering, are at the forefront of reshaping the reconstructive landscape. These innovations enable unprecedented levels of surgical precision and customization, while also holding the potential to address longstanding challenges like donor site morbidity and vascular integration in tissue-engineered constructs. The integration of digital health tools, AI-guided planning, and real-time intraoperative imaging further enhances clinical outcomes and surgeon confidence.63,64

Simultaneously, favorable reimbursement frameworks, public-private healthcare partnerships, and growing awareness among both patients and providers are accelerating the adoption of these advanced techniques.65 Developing healthcare markets are also beginning to recognize the value of investing in long-term, functional reconstructive outcomes, paving the way for more equitable access to state-of-the-art care.66

With ongoing clinical trials, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and global health initiatives aimed at improving education, training, and infrastructure, the future of vascularized breast reconstruction appears promising. The field is evolving beyond the goal of simply restoring form, toward a more holistic vision, one that empowers patients with meaningful choices, respects their individual journeys, and prioritizes both quality of life and long-term psychosocial well-being. In this light, vascularized reconstruction is not just a surgical procedure, but a critical component of comprehensive cancer survivorship.67

There is no funding to report on this study.

Jigisha Hota expresses appreciation to Professor Bill Tawil for overseeing the framework of this review, and for the insightful lectures and advice concerning biomaterials and tissue engineering, which contributed to the development of this paper.

Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Jigisha, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.