Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Case Report Volume 15 Issue 3

1Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Coordinator, Fundación San José de Buga, Professor of Paediatrics, Central Unit of the Valley, Colombia

2Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Colombia

3Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Fundación San José de Buga, Professor of Paediatrics, Unidad Central del Valle, Colombia

4Paediatrics Service, Fundación San José de Buga, Professor of Paediatrics, Unidad Central del Valle, Colombia

5Radiology Service, Fundación San José de Buga, Professor of Paediatrics, Unidad Central del Valle, Colombia

6Faculty of Health, Universidad del Valle, Colombia

7Faculty of Health, Universidad Javeriana, Colombia

Correspondence: Mendoza Tascón Luis Alfonso, Pediatrician and Neonatologist, MSc Epidemiology, Calle 12 A Sur #5-33, neighborhood El Albergue, Guadalajara de Buga, Valle del Cauca, Colombia, Tel +(57) 3155707422

Received: September 01, 2025 | Published: October 31, 2025

Citation: Mendoza LA, Mondragón ML, Mondragón HF, et al. Pyloric jaundice syndrome in a neonate. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2025;15(3):159-163. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2025.15.00602

What is known about the subject of this study?

Although there are publications on pyloric jaundice syndrome, most neonates who are admitted do so independently or due to unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia or emesis, with very few cases being admitted with pyloric jaundice syndrome. For our institution, this is the first case of pyloric jaundice syndrome among the 9730 discharges we have had since we opened our neonatal intensive care unit.

What does this study contribute to what is already known?

This case teaches us that we must suspect pyloric jaundice syndrome in neonates who are admitted with non-bilious emesis and unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is associated, regardless of the total bilirubin value and the age of the newborn. He calls on us to suspect the diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and to perform an ultrasound study of the pylorus when a neonate is admitted with jaundice and emesis.

Keywords: neonate, infant, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, hyperbilirubinemia, pyloric jaundiced syndrome

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is one of the most common surgical conditions in younger children that typically occurs between the 2nd and 12th week of life,1 although some cases are reported outside this period.1,2 It is most common in boys in a ratio of 4-6:1 and the median age is around day 40 of life.1,3 It is most common in boys in a ratio of 4-6:1 and the median age is around day 40 of life.1,4

HPS is a condition in which there is an elongation of the pylorus and a hypertrophy of its circular and, to a lesser degree, longitudinal muscle fibers, resulting in involvement of the pyloric canal and obstruction of the outlet of the stomach.5

Since 1977, ultrasound has been the test of choice for the diagnosis of HPS, and in most institutions, it has completely replaced contrast radiography for this purpose. The obvious advantage of using ultrasound is to avoid a dose of ionizing radiation. Ultrasound has gained space with better sensitivity and specificity, while palpation of the pylorus, which in the different studies had shown a sensitivity between 10% and 93%, has decreased over the years, perhaps due to the earlier presentation and/or less experience of the medical staff.6

On the other hand, hyperbilirubinemia at the expense of unconjugated bilirubin affects about 60% of full-term infants and 80% of preterm infants in the first week of life; however, it is less frequent after the second week of extrauterine life.7 Among the causes of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, apart from those related to isoimmunization by group and blood Rh, are congenital hypothyroidism, administration of sulfonamides, ceftriaxone, penicillins, intestinal obstruction, pyloric stenosis, jaundice due to breast milk, and suboptimal intake with breastfeeding.8

HPS and unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia are frequently diagnosed entities; however, the concomitant occurrence of the two is rare. Despite its rarity, hyperbilirubinemia has been described as associated with HPS.9,10 This hyperbilirubinemia has had various explanations, such as the reduction of hepatic activity of bilirubin, uridine diphosphate, glucoronyl transferase (UDPG-T), among other hypotheses10. The objective of this report is to describe a neonatal case of hyperbilirubinemia associated with non-bilious vomiting and pyloric HPS in an 18-day-old neonate at the time of admission.

A female neonate at term, 18 days of age, born vaginally, of adequate weight, height, and head circumference at birth, with positive blood group O, was referred to the pediatric emergency department with a 5-day history of postprandial emesis of non-bilious dairy content in projectile form, associated with marked mucocutaneous jaundice. She is the first daughter of a 32-year-old father with a history of similar symptoms during her childhood. A 27-year-old mother, OR positive, with adequate prenatal control.

On admission, she was hydrated, with adequate weight, height, and head circumference for her chronological age, with normal vital signs (Table 1). During her emergency care, she presented 4 emetic episodes. It is left on an empty stomach and with intravenous fluids of dextrose with electrolytes. Phototherapy was initiated due to significant unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, which was withdrawn the next day. An ultrasound of the abdomen and pylorus was ordered, and a pediatric surgery evaluation was requested.

|

Clinical feature |

Description |

|

Age at admission |

18 days |

|

Female sex |

|

|

Gestational age |

38 + 5/7 weeks |

|

Birth route |

Vaginal |

|

Birth weight in grams (percentile) |

2,435 (4.01) |

|

Height at birth in cm (percentile) |

48 (38.23) |

|

Head circumference at birth in cm (percentile) |

32 (11.67) |

|

Age of symptom onset |

13 days |

|

Clinical manifestations |

Five days of non-biolous dairy content emesis, in projectile a few minutes after being fed. |

|

Concomitantly, marked mucocutaneous jaundice was present. Mother and neonates with blood group O positive. |

|

|

Physical examination on admission |

Hydrated, weight 2,825 g, size 51 cm, head circumperimeter of 34 cm. Good clinical condition, systolic blood pressure 74 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure 42 mmHg and mean arterial pressure 55 mmHg, pulse rate 138 beats/minute, respiratory rate 48 breaths/minute, preductal saturation 96%, postductal saturation 94% and temperature 36.5°C. |

|

Surgery |

Pyloromyotomy at day 19 of life |

|

Condition at discharge |

Alive |

Table 1 Clinical features

Laboratories reported a normal blood count; normal sodium, potassium, and chlorine; elevated serum ionized calcium and magnesium; normal clotting times; elevated total bilirubin at the expense of the unconjugated fraction; and arterial blood gases with metabolic alkalosis (Table 2).

|

Laboratory |

Result |

Interpretation |

|

Cbc |

||

|

Hemoglobin |

13.4 d/l |

Normal |

|

Hematocrit |

36.7% |

Normal |

|

Leukocytes |

7,610/ mm3 |

Normal |

|

Neutrophils |

1,450/ mm3 |

Normal |

|

Lymphocytes |

5,040/ mm3 |

Normal |

|

Monocytes |

960/ mm3 |

Normal |

|

Platelets |

451,000/ mm3 |

Normal |

|

Metabolic |

||

|

Thyro-stimulating hormone |

4.54 mIU/l (0.3-4.2 mIU/l) |

Normal |

|

Total bilirubin |

19.97 mg/dl |

Elevated |

|

Unconjugated bilirubin |

19.24 mg/dl |

Elevated |

|

Coagulation tests |

||

|

Thromboplastin part-time |

36.6 segundos (24.5-33.8 segundos) |

Normal |

|

Prothrombin time |

10.7 segundos (9.9 – 11.8 segundos) |

Normal |

|

Serum electrolytes |

||

|

Sodium |

135 mmol/l (135-148 mmol/l) |

Normal |

|

Potassium |

4.87 mmol/l (3.5-5.1 mmol/l) |

Normal |

|

Chlorine |

100.1 mmol/l (98-107 mmol/l) |

Normal |

|

Magnesium |

2.75 mmol/l (1.7-2.4 mg/dl) |

Normal |

|

Ionized calcium |

1.48 mg/dl (1.1-1.3 mmol/l) |

Normal |

|

Arterial gases |

||

|

pH |

7.506 (7.35-7.45) |

Elevated |

|

PaCO2 |

37.8 mmHg (35-48 mmHg) |

Normal |

|

PaO2 |

80 mmHg (60-100 mmHg) |

Normal |

|

Exceso de base |

6.7 mmol/l (-2.0 ; 3.0) |

Normal |

|

HCO3 |

30.0 mmol/l (1.1-1.3 mmol/l) |

Elevated |

Table 2 Neonatal laboratories

Ultrasound of the abdomen. The liver, gallbladder, bile ducts, pancreas, spleen, right and left kidneys, bladder, and retroperitoneum are normal. Additional examination focusing on the pylorus reveals a pyloric canal diameter of 20 mm, a muscle layer thickness of up to 5 mm, and an anteroposterior diameter of the pyloric canal of 16.4 mm.

Conclusion: Ultrasound findings suggestive of developing pyloric hypertrophy, to be correlated with current clinical presentation (Figures 1–3).

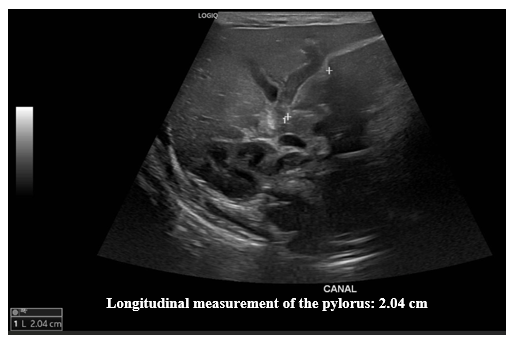

Figure 1 Pylorus ultrasound. Longitudinal measurement.

Ultrasound images of the pylorus showing a longitudinal measurement of 2.04 cm.

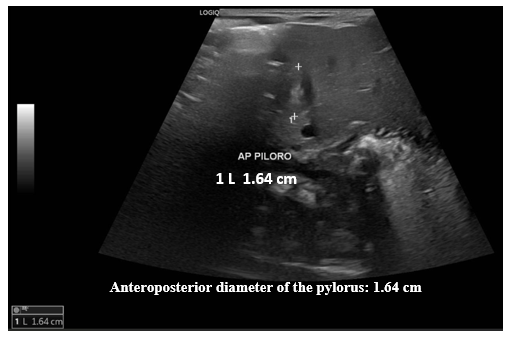

Figure 2 Pylorus ultrasound. Measurement of the anteroposterior diameter (AP) of the pylorus.

Ultrasound images of the pylorus identified an anteroposterior diameter of 1.64 cm.

Figure 3 Pylorus ultrasound. Measuring the thickness of the muscle layer.

Ultrasound images of the pylorus show a thickness of the muscle layer of 0.50 cm.

The day after admission, she underwent surgery under general anesthesia. After confirming the diagnosis, pyloromyotomy was performed with exposure of gastric mucosa (Figure 4). Hassle-free procedure. After this, he is transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit, where he finishes the clinical recovery until his discharge home.

Figure 4 Pylorus ultrasound. Measuring the thickness of the muscle layer.

Ultrasound images of the pylorus show a thickness of the muscle layer of 0.50 cm.

10 days after hospital discharge, the newborn was evaluated on an outpatient basis by pediatricians, who found the newborn in excellent clinical condition, with adequate weight gain, with an adequate breastfeeding process, without emesis and with a normal basic metabolic screening result (Table 3).

|

Metabolite evaluated |

Result |

Reference value |

Interpretation |

|

Hemoglobina A |

15.3% |

8.1% - 623.7% |

Normal |

|

Hemoglobina F |

84.7% |

49.9% - 98.4% |

Normal |

|

Thyro-stimulating hormone |

5.83 mUI/L |

Menor de 10 mUI/L |

Normal |

|

Immunoreactive trypsin |

19.8 ng/mL |

Menor de 60 ng/mL |

Normal |

|

Galactose neonatal |

<1.7 mg/dl |

Menor de 10 mg/dl |

Normal |

|

Fenilalanina neonatal |

<0.50 mg/dl |

Menor de 2.0 mg/dl |

Normal |

|

Biotinidase activity |

80 unidades |

Dpeficit grave hasta 58 U |

Normal |

|

17 Hydroxiprogesterone |

28.6 nmol/L |

Menor de 180 nmol/L |

Normal |

Table 3 Basic metabolic screening

This case report refers to a female term newborn who, at the end of the second week of life, began episodes of non-bilious projectile vomiting as a primary symptom of HPS. Bašković et al.,1 reported that HPS was a less frequent pathology in women (22.6%), with a median age of 31 days (interquartile range [IR]: 24-44 days), being more frequent in term neonates (90.6%), with symptom duration at diagnosis of 4 days (IR: 2-7 days). This study reported that one patient (1.89%) had a family history, indicating that one parent also had pyloric stenosis.

The association between hyperbilirubinemia and HPS has been described in the literature since 1955. Block MA,11 1965, described the pyloric jaundice syndrome in a three-and-a-half-week-old neonate. Chaves-Carballo et al.,12 described in 1969 three neonates and one minor infant with hyperbilirubinemia associated with HPS. Lippert,13 in 1986, reported a case of hyperbilirubinemia associated with HPS similar to our case with 17 days of life and an elevated bilirubin level at the expense of unconjugated bilirubin of 21.7 mg/dl.

The prevalence of pyloric jaundice syndrome has been described as between 2% and 8% in neonates and infants with HPS.10,14 Kwok15 reports an incidence of this association of 1.9%, which for Sieniawska et al.,16 was 17%, while Hua et al.,17 reported that pyloric jaundice syndrome had an incidence of 14.3% among 237 neonates with HPS. On the other hand, A.L. Hakeem et al.,18 reported that among 31 infants between three and six weeks of age with HPS, 100% presented vomiting and 48.4% hyperbilirubinemia.

Hyperbilirubinemia has been reported as unconjugated in most cases. Half of neonates with HPS-associated hyperbilirubinemia have unconjugated bilirubin levels between 5 and 10 mg/dL. However, other authors report higher levels of total and unconjugated bilirubin. Rhea et al.,19 reported a case with a total bilirubin of 21.5 mg/dl, a value similar to that of our patient. Bleicher et al.,20 a full-term male neonate who develops non-bilious projectile vomiting at 12 days of age and, at 15 days of life, is admitted to the hospital with total bilirubin of 46.1 mg/dl with an indirect fraction of 32.0 mg/dl. The pylorus was palpated on the third day of being hospitalized. Total bilirubin was increased to 50 mg/dl with an indirect dose of 46.1 mg/dl, requiring two exchange transfusions. On day 19 of life, pyloromyotomy was performed, with a rapid decrease in total bilirubin. Although our patient did not require an exchange transfusion, he did remain under conventional phototherapy for one day. Four cases reported by Chaves-Carballo et al.,12 had unconjugated bilirubin (mg/dl) levels of 16.2, 11.1, 24, and 26, respectively. These authors describe that in some neonates with HPS, hyperbilirubinemia appears at 2 days of age and resolves around 7 days, and then reappears at 2 or 3 weeks of age. Most neonates have unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in the first week of life; for other neonates, hyperbilirubinemia initially appears at 3 or 4 weeks of age.12

The literature mentions that non-bilious vomiting occurs more frequently between the second or third week of life,12 as occurred in our patient, who began with non-bilious vomiting at the end of the second week of life. However, some infants have vomiting in the first week and others at 4 weeks of age. Our patient initially consulted for jaundice and non-bilious vomiting simultaneously; however, the literature reports that in about 50% of cases, jaundice precedes vomiting, and in about 30%, jaundice appears after vomiting.12

The hypotheses to explain the association between total hyperbilirubinemia at the expense of the unconjugated fraction and idiopathic HPS mention the mechanical obstruction of the common bile duct by the pylorus, the imbalance of the autonomic nervous system that produces spasm of the common bile duct, dehydration with decreased bile flow and biliary stasis, a hepatocellular defect, decreased glucoronyl transferase activity, reduced hepatic blood flow with cellular anoxia, or competitive inhibition of bilirubin formation by breast milk steroids.20 Other authors summarize these hypotheses in the following proposals: A. Mechanical obstruction of the bile ducts by (1) angulation of the pylorus; (2) compression of the bile ducts by a lymph node, ligament, duodenal band, or scar; or (3) inflammation of the bile ducts. B. Decreased hepatic glucuronyl transferase activity is possibly related to (1) an inhibitory substance in the bile; (2) competition between pregnanediol and bilirubin for glucuronic uridine diphosphate acid; (3) decreased portal venous blood flow to the liver due to increased intra-abdominal pressure; (4) hypoglycemia; or (5) dehydration. However, the hypotheses associated with mechanical obstruction are difficult to accept since hyperbilirubinemias are of the unconjugated type, without dilation of bile ducts or biliary stasis. Other reports show progressive deterioration of glucoronyl transferase activity in the liver of rats after common bile duct ligation.12 Etzion et al.,21 evaluated some characteristics of duodenal fluid in 11 infants with HPS in an attempt to understand the mechanisms of hyperbilirubinemia in this event. However, they conclude at the end of their analysis that the unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia observed in some patients (36%) with HPS is not associated with bacterial overgrowth, changes in glucuronidase levels, pH, electrolytes, or biliary obstruction.

A compromise that is associated with a polymorphism in a promoter of the bilirubin-uridine diphosphate-glucoronyltransferase (UDP-GT) gene (UGTA1) with seven instead of six TA repeats in this region has also been described. Eylem et al.,22 demonstrated in a report after direct sequencing analysis of the promoter region of the UGT1A1 gene revealing a genotype of (TA) 6/7TAA in a 45-day-old patient with jaundice and recurrent vomiting caused by HPS. The study was extended to the fathers who were sequenced for the same region, and it was found that the mother was heterozygous for the same polymorphism ((TA) 6/7TAA), while the father was (TA) 6/6TAA.

It has also been postulated that serum gastrin inhibits glucuronyl transferase activity and that HPS hypergastrinemia causes the resulting unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.20 Hua et al.,17 obtained blood for mutation analysis from 17 infants with pyloric jaundice syndrome and 30 subjects with HPS of the same age, sex, race, breastfeeding, and disease activity among 34 neonates and infants with pyloric jaundice syndrome and 203 neonates and infants with HPS. These authors found a genotype of Gilbert's syndrome in 10.7% of infants with HPS, within the range known for the general population; however, they found a genotype of Gilbert's syndrome in 43% of infants with pyloric jaundice syndrome. For these authors, it appears that the severity of metabolic stress, as measured by increased bicarbonate and decreased chloride, plays a role in the manifestation of jaundice in infants with HPS. When controlling for all demographics and biochemical tests, the risk of having a mutation for Gilbert's syndrome is 4.1 times higher in pyloric jaundiced syndrome than in HPS. Trioche et al.,23 present three patients with jaundice associated with HPS. Two of them had a homozygous insertion of TA dinucleotide into the TATA box of the bilirubin glucoronyl transferase gene, and the third was heterozygous for the same TA dinucleotide insertion (whereas all 5 exons and exon-intron junctions were normal). These results suggest that jaundice associated with pyloric stenosis is due to molecular defects within the TATA box of the bilirubin glucoronyl transferase gene and suggest that this condition is an early manifestation of Gilbert's síndrome.

In terms of family history, Bašković et al.,1 describe in their report of 53 neonates with HPS that in one of their patients (1.9%) there was a history of HPS in the father of the newborn. Our patient also apparently had the history of the father of HPS in his neonatal stage. Other authors describe that the familial inheritance of HPS is found in about 15% of cases.17

Regarding the acid-base state, our neonate presented metabolic alkalosis on admission, without alteration of sodium, potassium, and chlorine, with increased ionized calcium and serum magnesium. Vomiting stomach contents on multiple occasions, as occurs in HPS, without loss of intestinal contents, leads to the loss of hydrochloric acid (HCl) secreted by the gastric mucosa, resulting in loss of acid from the extracellular fluid and the development of metabolic alkalosis, as occurred in our patient, being specific to newborns with HPS.1

In the report by Bašković et al.,1 blood pH was 7.457 (IQR: 7.425–7.517), pCO₂ 33.7 mmHg (IQR: 31.2–38.2 mmHg), pO₂ 60 mmHg (IQR: 54–65.2 mmHg), HCO₃ 25 mmol/L (IQR: 23–27 mmol/L), and excess base 0.8 mmol/L (IQR: -1.2; 2.9). Serum potassium, sodium, and chlorine (mmol/L) were 5 (IQR: 4.2-5.6), 137 (IQR: 136-138), and 103 (IQR: 100-105), respectively. Ionized calcium 1.28 mmol/L (RI: 1.25-1.31 mmol/L). Total bilirubin 2 mg/dL (<2-5.1 mg/dL). Vomiting for more than three days has been significantly associated with metabolic alkalosis1.

Ultrasound is the test of choice for the diagnosis of HPS. There are ultrasound parameters that allow the diagnosis of this entity to be made. Among these are the length of the pylorus, the muscle thickness and the diameter of the pylorus. However, there are variations in the measurements of these parameters. Piotto et al.,5 report studies where the measurements of these parameters vary, with pylorus length between 14-20 mm, muscle thickness between 2.5-4.8 mm, and pylorus diameter between 10-25 mm. In their study, Piotto et al.,5 found among 321 neonates without HPS an average length of 2.8 mm, standard deviation (SD) 0.6 mm; muscle thickness of 1.3 mm, SD 0.3 mm; and pylorus diameter of 8.2 mm, SD 1.1 mm. Among 286 neonates with HPS, the mean length was 16.3 mm, SD 2.3 mm, muscle thickness 2.9 mm, SD 0.5 mm, and pyloric diameter 38.4 mm, SD 18.5 mm. The ultrasound findings of our patient identified a diameter of the pyloric canal of 20 mm, a thickness of the muscle layer of up to 5 mm, and an anteroposterior diameter of the pyloric canal of 16.4 mm, all above normal values.

The sensitivity and specificity of pyloric thickness ≥3 mm and ≥4 mm have been reported, with sensitivity between 91.9% and 100% and specificity between 85.1% and 100%. Regarding sensitivity and specificity based on the length of the pyloric channel, the different reports report a sensitivity between 54.1% and 100% and a specificity between 89% and 100%. Regarding sensitivity and specificity based on pyloric diameter, sensitivity between 55% and 93% and specificity between 96.1% and 100% are reported. On the other hand, the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of childhood HPS based on combined measurements have sensitivity between 87.1% and 100% and specificity between 98.7% and 100%.6

According to the same authors, the most commonly used parameters were pyloric muscle thickness (≥3 mm or ≥4 mm) or a combination of pyloric muscle thickness (≥4 mm) and/or pyloric canal length (≥16 mm). Pooled sensitivity and specificity for both pyloric muscle thickness alone and in combination with pyloric canal length were high. However, pyloric muscle thickness ≥ 3 mm is only slightly more accurate than pyloric muscle thickness ≥ 4 mm or the combination of pyloric muscle thickness ≥ 4 mm and/or pyloric canal length ≥ 16 mm and is therefore preferable. The authors recommend using a pyloric muscle thickness ≥ 3 mm to confirm the diagnosis of HPS.

If ultrasound is positive for HPS in neonates or infants with non-bilious projectile vomiting, the patient should be sent to the operating room. In the case of a negative ultrasound, additional studies should be performed to exclude other causes of HPS. Additional studies may consist of clinical follow-up or repeated ultrasound, and a gastroduodenal series with contrast medium may be considered. Keep in mind that palpation of a pyloric "olive" has limited sensitivity.

This case report documents that we should suspect pyloric jaundice syndrome in neonates and infants with jaundice and non-bilious vomiting. It also supports the current diagnostic approach, demonstrating that ultrasonography in an experienced hand is a valid method for diagnosing HPS. If ultrasound is highly suspicious of HPS in a newborn or infant with projectile non-bilious vomiting, he or she should be operated on.

Although pyloric jaundice syndrome and Gilbert's syndrome appear to be two different conditions, in some selected patients, more laboratory tests with genetic studies must be obtained to make the differential diagnosis.

None.

None.

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

©2025 Mendoza, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.