Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 2

1Lieutenant Colonel, Classified specialist in Pediatrics, Combined Military Hospital, CMH, Bangladesh

2Lieutenant Colonel, Classified specialist in Surgery and Commanding Officer, Combined Military Hospital, Bangladesh

3Brigadier General, Advisor specialist in Pediatrics and Neonatologist, Combined Military Hospital, Bangladesh

Correspondence: Lt Col Nure Ishrat Nazme, Classified specialist in Pediatrics, Combined Military Hospital, CMH Bangladesh, Tel +8801817314349

Received: April 25, 2023 | Published: May 26, 2023

Citation: Nazme NI, Jafran SS, Sultana J. Knowledge and practice of caregivers for the management of their febrile children: Bangladesh perspective. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2023;13(2):93-98. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2023.13.00498

Background: Fever is the most common pediatric symptom and one of the most prevalent public health issues, which warrants frequent visits to the doctors. Evidence-based practices are widely lacking due to a scarcity of knowledge regarding the management of febrile children.

Objective: This study aims to determine caregivers' knowledge and practices for managing their febrile children and to assess the factors influencing these practices.

Method: This cross-sectional study was conducted at two military hospitals in Bangladesh. The study subjects comprised a convenient sample of 350 caregivers attending the OPD with a feverish child under twelve years.

Results: Knowledge about fever management was deficient in the majority of participants, in terms of fever definition, the Paracetamol dose, and frequency. Most of the participants were worried about febrile convulsions. Unsatisfactory practices were observed in regards to faulty temperature measurement, giving inadequate fluid to febrile children, and preferring antibiotics to reduce body temperature. Maternal age, education level of the mother, income of the family, number of children, occupation of the mother, type of family, and history of recurrent illness in children were found to be significantly associated with the knowledge and practice level of parents.

Conclusion: Poor knowledge and unsatisfactory practice of the parents regarding the management of their febrile children lead to undue concern, which increases the burden on healthcare facilities. It provides insight for healthcare providers to enhance parental expertise by offering evidence-based information and spreading awareness in the community to augment the general outcomes of febrile episodes in children.

Keywords: fever, febrile illness, children, knowledge, practices, antipyretic

Pediatric fever is a common symptom that is mostly caused by self-limiting infections. However, fever in children is often inappropriately managed by the parents, driven by a lack of appropriate knowledge and it leads to undue anxiety and frequent health care consultations.1,2 Globally fever accounts for more than 30% of healthcare visits. Many of these consultations could be avoided if the parents were informed about the initial fever management practices at home.3

Defining fever remains a subject of controversy with varied definitions by different authors.4 A slight rise in body temperature not higher than 37.8°C might be seen in the infants for teething or after vaccination or due to excessive clothing.5 However, most authors describe fever as a state in which core temperature is increased above the normal range (greater than 38°C).2,6,7 Fever occurs as a part of the host defense mechanism against exogenous pyrogens (temperature-raising chemicals released by inflammatory cells) including microbial pathogens.8 Nevertheless, a significant number of febrile children are diagnosed with self-limiting viral or non-complicated, milder forms of bacterial illness, which can be managed at home by the primary caregiver with supportive care measures like adequate rest and hydration.9 Therefore, the pediatric policy is not intended to treat the fever with medicines except for those who are sick and distressed or at risk for further complications.10 Still, the negative perceptions of fever, like fears of febrile seizures and brain damage, remain unchanged among the parents. All these misconceptions cause the mother's frustration, uncertainty, dissatisfaction with care, and unnecessarily aggressive and inappropriate management of feverish children for speedy reduction of the temperature.10,11

The fever phobia remains extremely widespread all over the world and the scenario is almost the same in different international studies.2,12–14 Inappropriate practices include measuring temperature by hand, providing an inappropriate dose of antipyretics, cessation of breastfeeding in febrile children, making iced-cold water sponging or baths, and rubbing the child's body with alcohol, vinegar, or lemon.15–17 In addition to the over or under-dosing of antipyretics, the substantial misuse of antibiotics to manage pediatric fever by over-concerned parents is frequently associated with antimicrobial resistance, a global issue for developing countries.2,18 The parents' anxiety and dissatisfaction may sometimes lead to repeated consultations with different doctors, and increased hospital admissions thereby increasing the burden and cost to the healthcare setup.19

Literature suggests that effective educational programs targeting specific knowledge, beliefs, and practices are of paramount importance to modify caregivers’ incorrect knowledge, phobic beliefs, and practices regarding the management of febrile children.9,10 Therefore, at the first step, it is essential to recognize, what self-control activities they practice, and which factors contribute to their knowledge and behavior gap. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies on the knowledge of caregivers regarding childhood fever in Bangladesh and therefore, evidence regarding the current state of knowledge and practices of the caregivers and the diffusion of new recommendations are crucial.

This cross-sectional study was conducted from September 2022 to February 2023 involving all the parents or caregivers who attended the Pediatric Outpatient Departments (OPD) of two organizations. The first half of the cases were collected from Defence Services Command and Staff College (DSCSC), Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka which is a training institute for military officers and comprises a medical inspection room including outdoor services of different subspecialties. The rest of the cases were taken from CMH Ramu, Ramu Cantonment which is a 299 bedded tertiary level hospital of Bangladesh Army, placed at Cox’sBazar, Bangladesh. Around 30 pediatric patients report to the OPD of these hospitals every day on average during working hours. A convenience sample of 350 mothers, fathers, or attendants other than parents (actively playing the role of primary caregiver of the respected child) who attended the OPD with a complaint of fever in their child under twelve years and agreed to participate in the study was purposively selected as the study subjects. Only one respondent for each case was selected as the study subject. The attendants who refused to participate or contacted the doctor over the phone were excluded from the study.

Data collection

A close-ended questionnaire was developed by the researcher after a thorough review of relevant related literature and accomplishing a pilot study on 20 mothers. The clarity and applicability of the questionnaire was checked, and necessary modifications were made accordingly. The participants who participated the pilot study were excluded from the final results. The questionnaire consisted of four parts. It included mainly the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants including age, education, residence, occupation of mother, type of family and family income (1st part); difficulties encountered by parents while managing febrile children (2nd part); and level of knowledge (3rd part) and practice (4th part) in multiple dimensions regarding the management of their children when they suffer from febrile illness. Most of the responses were labeled as ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ except for the socio-demographic features. Participants were scored one (1) for a correct answer and zero (0) for an incorrect answer in terms of scoring knowledge and practice level.

Ethical consideration

Informed written consent was obtained from every participant after explaining the aim of the study. Privacy and anonymity were ensured during data collection. The confidentiality of data was always ascertained and the participants were assured that the information will be used for the research only. The participants and their children had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Official approval for the study was obtained from the authorized ethical committee.

Statistical analysis

After data collection, data were coded manually, then, data were entered and analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) version 26.0. Quantitative data were described using mean ± standard deviation and median (minimum-maximum) where appropriate. Qualitative data were described using numbers and percentages and the chi-square test was performed for the comparison of categorical data. The p-value was considered to be significant at ≤0.05.

A total of 350 caregivers responded to the questionnaire, and their detailed sociodemographic characteristics were shown in Table 1. Most respondents were mothers (96%, n=335) among whom nearly two-thirds (67%) were in the young age group (20 to 30 years). The mean age of the mothers was 25.9±5.5 years with the minimum to maximum age range from 17 to 43 years. More than half of the mothers (74%) were at the undergraduate level and acted as homemaker (86%). The majority of the respondents came from urban areas (87%). Most of the families (97%) were nuclear variety and solvent (89%). Most of the participants (78%) had 2 children, followed by 3 children or more (13%) and 1 child in 9% of cases. Knowledge of the respondents about fever was assessed in Table 2. Only 18 respondents (5%) had correct knowledge about the definition of fever. Regarding the use of Paracetamol, 48 cases (14%) had adequate knowledge about the age-appropriate dose and 92 parents (26%) knew the frequency of Paracetamol insertion. About 41% (n=144) of respondents had overall good knowledge versus 59% (n=206) having poor knowledge.

|

Characteristics of parents of febrile children |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

|

Respondent |

||

|

Father |

11 |

3 |

|

Mother |

335 |

96 |

|

Attendants other than parents |

4 |

1 |

|

Mother’s age in years |

|

|

|

<20 |

25 |

7 |

|

20-30 |

234 |

67 |

|

30-40 |

87 |

25 |

|

>40 |

4 |

1 |

|

Min.-Max. |

17 - 43 |

|

|

Mean ± SD |

25.9 ± 5.5 |

|

|

Level of mother’s education |

|

|

|

Illiterate |

0 |

0 |

|

<Secondary education (SSC) |

22 |

6 |

|

<Higher Secondary education (HSC) |

30 |

9 |

|

HSC completed |

205 |

59 |

|

University education completed |

67 |

19 |

|

Postgraduate education |

8 |

2 |

|

Technical education |

18 |

5 |

|

Residence |

|

|

|

Urban |

305 |

87 |

|

Rural |

45 |

13 |

|

Occupation of mother |

|

|

|

Working |

48 |

14 |

|

Not working (Home maker) |

302 |

86 |

|

Type of family |

|

|

|

Nuclear |

339 |

97 |

|

Extended |

11 |

3 |

|

Family income |

|

|

|

Sufficient for maintaining a family |

312 |

89 |

|

Insufficient for maintaining a family |

38 |

11 |

|

Number of children |

|

|

|

One child |

32 |

9 |

|

Two children |

273 |

78 |

|

Three children or more |

45 |

13 |

|

Mean ± SD |

2 ± 0.5 |

|

|

Total |

350 |

100 |

Table 1 Distribution of caregivers’ sociodemographic characteristics; (n=350)

|

Pattern of knowledge |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

Correct knowledge about fever definition |

||

|

Yes |

18 |

5 |

|

No |

332 |

95 |

|

Correct knowledge about Paracetamol dose |

||

|

Yes |

48 |

14 |

|

No |

302 |

86 |

|

Correct knowledge about the frequency of Paracetamol |

||

|

Yes |

92 |

26 |

|

No |

258 |

74 |

|

Overall knowledge about managing febrile children |

||

|

Good |

144 |

41 |

|

Poor |

206 |

59 |

|

Total |

350 |

100 |

Table 2 Knowledge of respondents about fever; (n=350)

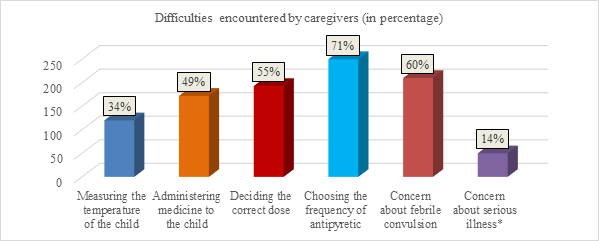

Parents' practice regarding home management of febrile children showed wide variability (Table 3). Here we have seen that seldom caregivers (14%) used a thermometer for measuring temperature, 95% of them preferred the armpit as the site of measuring body temperature. Oral route was the best choice for antipyretic in 95% caregivers. More than half of them (54%) had no practice of sponging their febrile children and only 15% gave more fluid to their sick children with fever. Other than antipyretics, 35 caregivers (10%) used different traditional methods for reducing the temperature in their children and 42% of them preferred antibiotics at the early onset of fever. Overall practice level was adequate in 37% of cases (n=129) whereas poor practice level was discovered in 63% (n=221) cases. Figure 1 manifests the difficulties encountered by caregivers. Selecting the appropriate antipyretic dose for febrile children was an important challenging issue for many caregivers (55%), next to difficulty in choosing the frequency of antipyretics (71%). Around 60% of participants expressed their anxiety about the propensity of convulsion due to fever, and 14% of them assumed fever as an indication of some serious illness.

|

Practice domain |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

Way of measuring body temperature |

||

|

By hand |

300 |

86 |

|

With thermometer |

50 |

14 |

|

The preferred site for measuring body temperature |

||

|

Armpit |

332 |

95 |

|

Oral cavity |

18 |

5 |

|

The preferred route of antipyretic |

||

|

Oral |

332 |

95 |

|

Per rectal |

18 |

5 |

|

Sponging/cold compress in fever |

||

|

Yes |

162 |

46 |

|

No |

188 |

54 |

|

Increase in fluid intake during fever |

||

|

Yes |

53 |

15 |

|

No |

297 |

85 |

|

Try traditional method† |

||

|

Yes |

35 |

10 |

|

No |

315 |

90 |

|

Prefer antibiotics for febrile children |

||

|

Yes |

148 |

42 |

|

No |

154 |

44 |

|

Overall practice about managing febrile children |

||

|

Good |

130 |

37 |

|

Poor |

220 |

63 |

|

Total |

350 |

100 |

Table 3 Caregivers’ practice regarding home management of childhood fever; (n=350)

†Using herbal or homeopathy drugs, Ice cooling of the body

Figure 1 Difficulties encountered by caregivers (n=350). *Brain damage, dehydration, coma, death, etc.

Table 4 shows the factors affecting the knowledge and practice of parents regarding fever. The significant factors for knowledge and practice of parents were (P value ≤0.5) maternal age, education level of the mother, income of the family, number of children, occupation of the mother, type of family, and history of recurrent illness in children. There was no strong correlation between parental knowledge and practice with having a child with febrile convulsion. Younger (<30 years old) and undergraduate mothers had significantly poor knowledge and practice regarding managing their febrile children. The case was the same in non-solvent parents, parents having a single child and living in an extended family. On the contrary, working mothers and mothers having children with chronic or recurrent illnesses seemed to be significantly confident in managing febrile children with better knowledge and practice experience.

|

Characteristics |

Knowledge score |

Practice score |

||||

|

Good |

Poor |

P-value |

Good |

Poor |

P-value |

|

|

Mother’s age |

||||||

|

< 20 |

0 |

25 |

0 |

25 |

||

|

20-30 |

85 |

149 |

0.000 |

83 |

151 |

0.000 |

|

30-40 |

57 |

30 |

45 |

42 |

||

|

>40 |

1 |

3 |

||||

|

Mother’s educational level |

||||||

|

Below University level |

67 |

190 |

0.000 |

69 |

188 |

0.000 |

|

University and above the level |

77 |

16 |

77 16 |

60 |

33 |

|

|

Income of family |

||||||

|

Solvent |

140 |

172 |

0.000 |

126 |

186 |

0.000 |

|

Not solvent |

4 |

34 |

3 |

35 |

||

|

Number of children |

||||||

|

Single child |

2 |

30 |

0.000 |

1 |

31 |

0.000 |

|

Two children |

127 |

146 |

114 |

159 |

||

|

Three or more children |

15 30 |

14 |

31 |

|||

|

Occupation of mother |

||||||

|

Working |

36 |

12 |

0.000 |

24 |

24 |

0.042 |

|

Not working (Home maker) |

108 |

194 |

105 |

197 |

||

|

Type of family |

||||||

|

Nuclear |

144 |

195 |

0.005 |

129 |

210 |

0.010 |

|

Extended |

0 |

11 |

0 |

11 |

||

|

History of affected child with febrile convulsion |

||||||

|

Yes |

17 |

22 |

0.742 |

12 |

27 |

0.403 |

|

No |

127 |

184 |

|

117 |

194 |

|

|

History of affected child with recurrent illness |

||||||

|

Yes |

28 |

17 |

0.002 |

23 |

22 |

0.034 |

|

No |

116 |

189 |

106 |

199 |

||

|

Total |

|

|

350 |

|

|

100 |

Table 4 Factors associated with the knowledge and practice of caregivers regarding childhood fever; (n=350)

Fever is considered a foremost disease symptom in children. Accurate knowledge of the caregivers is therefore crucial which could affect the attitude and performance while initial monitoring and management of a febrile child.20 In this regard, we investigated the level of knowledge and practice of the Bangladeshi parents or primary caregivers towards childhood fever, using a self-administered questionnaire. In the present study, most of the participants were mothers (96%), as fathers were mostly available in their respective working places and could not accompany their wives. We considered 4 grandmothers (01%) as the participants of the study due to the unavailability of working parents at the hospital, who were the primary caregivers of the children and expected to reflect almost the same knowledge and practice as the parents of the children.

The majority of participants were young mothers (67%) which is very close to other studies.21 Here, more than half of the mothers (74%) were at the undergraduate level which goes with the studies from Egypt and, Malaysia.1,22 Alex-Hart, & Frank-Briggs, contradicts the present study finding who concluded that 66.2% of the mothers completed graduation.23 The level of parents' literacy is an important factor contributing to the overall health care of children and uncompleted education might lead to insufficient knowledge and unsatisfactory practices.20 The majority of the respondents of the current study came from urban areas (87%) which go with the study by Abdinia and colleagues.17 In contrast, other studies revealed that the maximum number of participants resided in rural areas.20 The families residing in rural areas are attributed to the limited access to health services, thereby carrying poor knowledge and practice skills for managing their sick children.20

The present study showed that unemployed mothers formed the greatest proportion of the sample (86%) (Table 1). This finding coincided with Arica et al., who reported that 91% of the mothers were housewives.24 On the contrary, more than half of the mothers were employed in a study by Athamneh and colleagues.14 Alike Al-Eissa and colleagues, most of the families (97%) in our study were nuclear variety and only 3% were extended type.13 Only 11% of the participants of our study had a low household income level which favors a study from Ireland and contradicts another Malaysian study.22,25 At the time of the study, most of the participants (78%) had 2 children which were almost similar to the study by Hamideh.21

The study gave more insight into the parental knowledge and practice towards managing their febrile children. It showed lacking parental knowledge of the exact definition of fever (Table 2). According to Das and colleagues, a high body temperature of 38.0°C or more when measured rectally, 37.5°C or more when taken orally, and an axillary temperature of 37.2°C or more, are all considered a fever.17,26 Considering the influence of external factors like physical exercise, warm clothing, hot or humid weather, or warm food/drinks on high rise in temperature above 38.0°C, they should be eliminated before measuring the temperature.26 A gross misconception about defining fever was observed in many international studies including ours.16,17,26 Parents still tend to give antipyretics to their febrile children perceiving fever at a lower temperature.19 On the contrary, some other studies reported better knowledge scores regarding fever’s definitions (>38˚C in general) among parents.13,27

In the present study, poor responses were reported regarding the mothers’ knowledge about proper dosing and frequency of antipyretics (Table 2). These results were concordant with the findings of other studies.16,26 The dose calculation of antipyretics should be according to the child’s weight and increasing the dose, and frequency is not beneficial and not recommended in managing pediatric fever. In different studies, mothers had good knowledge about antipyretic usage.1,16,27 In agreement with other studies, more than half of the caregivers (59%) had overall poor knowledge regarding management of their febrile children.14,21,27

Parents’ practice regarding home management of febrile children showed a wide variability (Table 3). In the present study, the site used for the recording of body temperature was most commonly by touching the forehead by hand (86%), while 95% reported the armpits of the child as the site to measure temperature which were similar to many other studies.17,19 On the contrary, the results of some studies revealed better responses regarding the use of thermometers to determine the existence of fever in children.27 The NICE guideline advises against the use of rectal measurements because of safety concerns and indicates that tympanic or axillary methods are preferred despite being less accurate.28 This statement is in the agreement with the daily practice of healthcare professionals in different countries, and axillary measurement using a digital thermometer is generally recommended in all febrile children at home.29 In this study, 95% of parents preferred oral administration of antipyretics to rectal administration like in earlier research.25 Considering the greater risk of overdose due to the rectal administration of Paracetamol, rectal dosing is recommended based on the child’s body weight to ensure the child’s safety. Administration of rectal Paracetamol is encouraged under any conditions that prevent oral administration such as vomiting or refusal.4

Physical temperature-reducing methods such as peripheral cooling by cold application and rubbing the body with alcohol are practiced in different countries which are not recommended, as their usage may be associated with adverse effects like a paradoxical increase in fever (cold application) and hypoglycemia, coma even death (alcohol rubbing)4,27 Using Iced water for sponging is also a wrong action, still used by many parents which increases the risk of chills and a rapid drop in the child’s body temperature that eventually might cause brain damage.16,17 Bathing with warm water, and applying warm compresses to a febrile child have been used as good practices without major complications.12 Still, tepid sponging is of limited value and is not to replace the use of antipyretic, hence it is better to avoid it if it makes the child shiver, cry, or be uncomfortable. The feverish child should not be forced to eat against his or her will, but a high fluid intake is important to prevent dehydration.10,12 In our study, more than half of the parents (54%) had no practice of sponging their febrile children and only 15% gave more fluid to their sick children with fever which seems to be a good practice (Table 3). Some studies reported other traditional practices in a wide range, including administering homeopathic or herbal medicines, which was observed in the present study only in 10% of cases.27 In the present study, 42% of participants preferred antibiotics to reduce fever in their children, similarly in other studies.1,16 A substantial population also agreed to frequent physician visits, influencing the physician to prescribe antibiotics or even changing the doctor in case the fever doesn’t resolve early.19 This attitude may lead to the irrational use of antibiotics leading to the development of antimicrobial resistance.30 Overall inadequate practice was observed in 63% cases of our study which goes in favor of other studies.14,21,27

Caregivers faced a lot of difficulties while managing their febrile kids expressed in Figure 1 which coincides with other studies.26 As in our study, a variety of concerns regarding the harmful effects of fever were documented by mothers in different studies including fear of convulsion, brain damage or stroke, coma, dehydration, blindness, and death.26,27 Fortunately, fever in children rarely reaches high temperatures (above 41°C) and usually doesn’t cause any brain damage.10 A febrile seizure is also a rare complication of fever, which occurs in 2-4% of febrile children and most are self-limited without any long-term sequelae. The most common side effects of fever are benign and include minimal dehydration, increased sleepiness, and discomfort.26

According to Hussain and colleagues, cultural backgrounds, socioeconomic status, and educational levels are the major determinants of the level of knowledge and management of febrile children which was consistent in our study (Table 4).27 In this study, younger (<30 years old) and undergraduate mothers had significantly poor knowledge and practice regarding managing their febrile children. This is in line with the previous finding by other authors.2,21,27 The present study echoed the reports by Bong and Waly, where high-income group or solvent parents were found to have better knowledge and practice levels in comparison to those from low-income categories.1,22 This finding may be explained by the fact that the majority of the mothers from lower socioeconomic status may prefer to take advice from relatives and neighbors for managing the fever to save the cost of visiting a physician or health care facility. In our study, where health service was free of cost, the lower income groups might correlate with lower educational status and thereby hampering adequate knowledge gaining.

Parents of this study, having increased number of children were more confident in managing febrile children (Table 4), which is similar to Hamideh and Hussain’s findings.21,27 The scenario is same for the caregivers having children with any chronic or recurrent illness. Successive dealing with same sort of symptoms might make the parents having multiple children more knowledgeable and confident. On the contrary, no significant correlation was found in our study, between knowledge-practice level and parents having children affected with febrile convulsion. In our study, mothers from extended families showed poor knowledge and practice level, which was concordant with another study by Hussain and colleagues.27 This issue might reflect a poor level of confidence and increased anxiety of mothers due to overinfluence of other family members. The present study showed that working mothers had a better level of knowledge and practice in comparison to those who are homemakers. This finding coincided with Arica and colleagues.24 This may be attributed to the fact that working mothers' knowledge and their drive to evidence-based practices in caring for their feverish children make them more confident.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in our country to specifically explore parents’ knowledge, concerns, and practice regarding the management of their febrile children. As with all research of this nature, interviews were restricted to those who agreed to participate, which may have excluded parents of children having more vision. All participants were from a single station of Defense services, and there was limited demographic diversity, hence cannot be generalized to the varied and large Bangladeshi population. So, there is a chance of selection bias. But we tried to gain a range of participants on other dimensions (Table 1), such as parental age, working mother, and the number of children, etc. The large sample size (n=350) and high response rate are the major strengths of this study. On the other hand, the main limitation of this study is related to the cross-sectional design, which cannot provide temporality. Our study represented a large population of educated and solvent parents with an easy accessibility of healthcare setup which may not be the reality in the whole community. Therefore, opportunities to perform further studies in different localities of Bangladesh with the diverse socioeconomic background are yet to think.

There is a lack of knowledge and conflicting information regarding fever and febrile illness among caregivers of children which is reflected by inadequate attitude and practice towards initial home-based management of febrile children. This remains a primary concern to the health care workers as they are frequently subjected to parental anxiety, and repeated consultations, with an unnecessary burden on the health care services. This emphasizes the need for the implementation of various educational programs and interventions from the government and media along with the formulation of an evidence-based national guideline on the management of febrile children in Bangladesh, to empower parents in disseminating correct information for the care and management of children with febrile illness.

The authors thank all parents and other caregivers who contributed to this research.

Lt Col Nure Ishrat Nazme: Conceptualized the study, collected analyzed, and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript;

Lt Col Sardar Shahnabi Jafran: Edited the manuscript;

Brig Gen Jesmin Sultana: supervised the course of the study and the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

©2023 Nazme, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.