Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Case Report Volume 13 Issue 1

1Department of Neonatology, Mediclinic Alnoor Hospital, UAE

2Department of Neonatology, SSMC, UAE

3Department of Pediatrics and Neonatology, NMC Hospital, UAE

4Retired Neonatologist, UK

Correspondence: Dr. Mohamed Lotfy Eldawy, Department of Neonatology, Mediclinic Alnoor Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE, Tel 00971529064016

Received: January 28, 2023 | Published: February 6, 2023

Citation: Eldawy ML, Osman RE, Laban M, et al. A case report of mispositioned bilateral catheterization of the umbilical arteries in a neonate and review of the literature. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2023;13(1):15-17. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2023.13.00484

Background: Arterial catheters are frequently needed to optimize the intensive care in the sick newborn. Umbilical Arterial Catheters (UAC) is more popular than peripheral arterial catheterization. They are utilized to provide continuous accurate arterial blood pressure monitoring, frequent assessment of gas exchange efficiency, frequent blood sampling and rarely for exchange blood transfusion. Umbilical Arterial Catheters may be used in emergencies to infuse fluids or medications in the absence of venous access. Malposition of the Umbilical Arterial Catheter requires immediate attention. The main complication of UAC malposition is obstruction of the arterial lumen of a small caliber branching artery. This may lead to impedance of arterial flow and predisposes to arterial thrombosis and embolism.

Case Presentation: We present a rare case of bilateral UAC catheterization where the second umbilical artery was erroneously catheterized instead of the intended umbilical vein.

Conclusion: This case reinforces the need for thorough assessment of the position and course of any recently inserted umbilical vascular catheter.

Keywords: UAC, UVC, malposition, misposition

Case report

A 38+3 weeks term neonate, with a birth weight of 3517 grams, was mechanically ventilated on day 2 of life for ventilator failure arising from early onset pneumonia complicated by non- tension Pneumothorax. Umbilical venous catheter (UVC) and umbilical arterial catheter (UAC) were planned. The invasive lines were inserted by 2 different neonatologists. Both procedures were completed smoothly at first attempts. The catheters were fixed at the appropriately calculated distances. The back flows from both catheters were fluent and non-interrupted. Invasive blood pressure monitoring was commenced on the presumed arterial line. Appropriate arterial pulse waveforms and blood pressure readings were observed. This confirmed the placement within an arterial vessel. One milliliter per hour of physiological saline was infused through the presumed umbilical venous catheter pending confirmation by the x- ray.

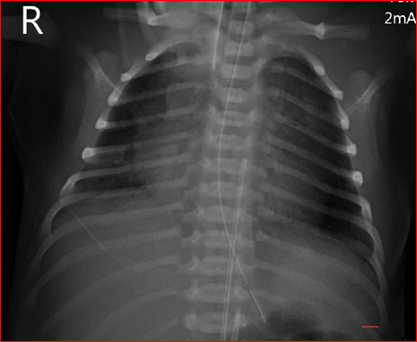

The x-ray (Figure 1) confirmed the position of the both lines at thoracic vertebra 7 levels (T 7) for the UAC and thoracic vertebra 10 level (T10) for the presumed UVC. The X- ray included the chest only and hence the whole courses of both catheters were not identifiable. However, they both looked heading toward the left side of the vertebrae. Dextrose 10% was infused through the lower central line which is presumed to be UVC, while antibiotics were given through peripheral venous line as per the neonatal unit policy.

Figure 1 (First X-ray: Two vascular catheters were identified with the tips positioned at level T7 and T10 thoracic Vertebrae, The view did not include full course of the catheters).

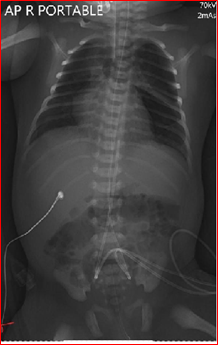

A repeat x-ray (Figure 2) including both chest and abdomen was performed on the following morning as the first X-ray did not demonstrate the whole course of both catheters. The second X-ray demonstrated that both the catheters were in the umbilical arteries. The catheter that ends at T10 (lower UAC) was catheterized via the right umbilical artery and the UAC that ended at T7 was catheterized via the left umbilical artery.

Figure 2 (Second X-ray: The two vascular catheters were identified as umbilical arterial catheters).

The lower positioned umbilical arterial catheter was removed promptly. The subsequent course of the baby was uneventful. There were no observed complications arising from the bilateral catheterization of the umbilical arteries. The baby was monitored for signs of ischemic manifestations to the lower limbs. Blood pressure and urine output were continuously monitored and appropriate for age. There were no adverse effects stemming from the bilateral catheterization of the Umbilical arteries despite the significant partial occlusion of the abdominal aorta. The baby was discharged in good general condition. Blood pressure, peripheral perfusion and renal function remained normal at 1, 3 and 6 months of follow up.

To our knowledge this is the first reported case of bilateral catheterization of the umbilical arteries.

UAC and UVC are key procedures during provision of neonatal intensive care especially in the first few days of life. UAC are used as a credible and durable arterial access for continuous accurate blood pressure monitoring, frequent blood gas assessment and repeated blood sampling.1 Umbilical vein catheterization is a reliable central venous access. The main uses are for administering fluids, medication infusions; parenteral nutrition and blood products.2 It may be used for measurement of central venous pressure.3 Both UAC and UVC are utilized to perform exchange blood transfusions.4

The location of the tip of UAC and UVC should be ascertained and monitored, as malposition or migration can cause various complications. These complications may occasionally lead to significant morbidity and even mortality.5

There are various reports in the literature of complications related to umbilical arterial catheterization including air embolism, thromboembolic complications, and vessel perforation.6,7 Other reported complications include refractory hypo glycaemia which had been observed when glucose-containing fluids were infused where a catheter tip was near the coeliac axis and mesenteric arteries.8 Mal-positioning of the UAC is of common occurrence.9,10 Furthermore, occlusion of the mesenteric arteries can result in gut ischemia, bowel infarction, and necrotizing enterocolitis.11 Occlusion of the renal artery may lead to hypertension or acute renal failure.11 Arrhythmias and catheter rupture are rare but recognized complications.12

Molanus et al.13 (BMJ 2017) reported a case of Umbilical Artery perforation following UAC which led to severe hemorrhagic shock, subsequent renal failure and severe periventricular leukomalacia. A case of transected segment of the UAC which migrated to the right internal iliac artery was reported by Doodnath R et al.14 in Journal of Neonatology 2022. The baby underwent laparotomy to retrieve the transected UAC segment. A more recent case of transected umbilical artery catheter in an 840 gram new born was reported in 2022 by Maggioni A, et al.15 in the British Medical Journal.

Aortic aneurysms are rare but recognized complications of UAC insertion.16 Jeffrey Mendeloff MD, et al.,16 in the Journal of Vascular Surgery 2001, presented a case of aortic aneurysm including a comprehensive literature review as well as management algorithm of this rare complication.

Our case highlighted the importance of ascertaining the correct placement of the umbilical arterial catheters. The tip of the UAC should be placed in one of two locations, high position at T6 -T9 level or low position at L3 - L4 level.17 High placement appears to have fewer complications.18 It is highly recommended to avoid positions which are between T10- L3 due to the potential for associated thrombosis of major aortic branches.17

The location of the catheter within the aorta and the position of catheter’s tip should be ascertained with AP x-ray examination of a combined abdomen and chest film. Lateral chest-and-abdominal radiograph are occasionally added if the AP films are inconclusive. The characteristic x-ray appearance should show the catheter passing through the umbilical stump in an inferior direction through the umbilical artery, traversing the anterior division of the internal iliac artery, into the common iliac artery. At this point, the catheter should be seen curving cephalad to approach the aorta. It should then proceed inside the aorta in a straight line which is clearly towards the left side of the vertebral column. It is essential to ensure that the tip of the catheter is not in a branch of the aorta. Furthermore, it is of vital importance to ensure the single x-ray film includes both the abdomen and the chest views. An umbilical venous catheter may be mistaken for an umbilical arterial catheter if the full radiological anatomical course is not exposed. Umbilical venous catheters travel cranially from the point of entry inside the umbilical vein while the umbilical arterial catheter travels inferiorly from the point of entry inside the umbilical artery to reach the common iliac artery.

Over the last few years ultrasound and targeted echocardiography have emerged as better tools for identification of the catheter course and localization of the tip.18 Ultrasound or targeted echocardiography are more accurate than the x-rays as they provide real-time assessment of the tip position and precise catheter course.18 Their added advantages are the radiation free environment and the quick procedure time as the waiting time for radiology will be spared. They require minimal training and involve minimal handling of the neonate. Furthermore, they can be used as a safe tool to help identification of migration of central lines as well as real time repositioning of umbilical and central lines. The present evidence shows good sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value when compared with a radiograph.19

Malposition of the umbilical arterial catheters should be rectified immediately. Unacceptable positions include the location of the catheter’s tip outside the recommended sites described above. Malposition of umbilical artery line in left iliac artery in particular carries a high risk of thrombosis and lower limbs thromboembolic complications.20 Folded catheters within the abdominal aorta should be removed.

The presence of 2 vascular catheters within the aortic lumen, as in our case, should be avoided. One of the catheters should be removed with urgency. The abdominal aorta mean diameter at the level of the diaphragm is 5.4 mm in an average weight term newborn and 4.8 mm in a preterm baby weighing 1 kilogram. A 3.5F umbilical catheter have a diameter of approximately 1.1 mm while a 5F catheter have a diameter of approximately 1.6 mm. Multiple or folded catheters within the aorta lead to significant narrowing of the aortic lumen with the potential of impeding the blood flow as well as predisposition to aortic thrombosis. This can lead to catastrophic sequelae including mortality, limb amputation and permanent hypertension.

Key points

None.

None.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

©2023 Eldawy, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.