Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6445

Review Article Volume 3 Issue 4

University OUCOM, Ohio, USA, WCMC, Qatar

Correspondence: Adel Sleiman Zaraa, Professor of Clinical Psychiatry, University OUCOM, Ohio, USA, WCMC, HMC, ED, Po Box 3050, Doha, Qatar, Tel 974 3342-7277

Received: September 09, 2015 | Published: September 9, 2015

Citation: Zaraa AS, Abdulla MAL, Abdallah W, aborabeh M, Mahmoud S (2015) Prevalence of Antipsychotic Polypharmacy: Prescribing Practices at the Psychiatry Department at HMC (Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar). J Psychol Clin Psychiatry 3(4): 00140. DOI: 10.15406/jpcpy.2015.03.00140

Combining antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders is relatively common. Rates in the literature have varied with an average ranging from 10% to 40%.1 A recently published systematic review that summarized 173 studies reporting on rates and correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy from the 1970s to today in over 1.5million patients found that the overall mean antipsychotic polypharmacy rate was 26%.2 Concerns about antipsychotic polypharmacy include the possibility of higher than necessary numbers of medications, greater than necessary total dosages, increased acute and long-term adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, increased non-adherence, difficulties in determining the effect of each treatment, substantially higher cost, a risk for increased mortality, and the general lack of evidence for the effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic polypharmacy.3‒8

It is our observation that despite the lack of clinical evidence, the anti-psychotic prescribing practices are very prevalent in our department. So far there was no quantitative or qualitative study that looked into this important issue. But there is little literature evidences found regarding the benefits of adding another antipsychotic. We are set to review the prescribing practices at the department of Psychiatry, HMC, in regard to the Antipsychotic polypharmacy, and see how it compares to the international general psychiatric practice then compare it to the existing guidelines. The results are discussed, recommendations are drafted and we plan on follow up in a separate yet later study the progress we would made in bringing about any change in the prescribing behavior after a remedial one year of educational intervention.

Keywords:polypharmacy, antipsychotics, treatment of psychotic disorders

Concerns about antipsychotic polypharmacy

Concerns about antipsychotic polypharmacy include the possibility of higher than necessary numbers of medications, greater than necessary total dosages, increased acute and long-term adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, increased non-adherence, difficulties in determining the effect of each treatment, substantially higher cost, a risk for increased mortality, and the general lack of evidence for the effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic polypharmacy.3‒8

Regional and geographic differences in prescribing practices

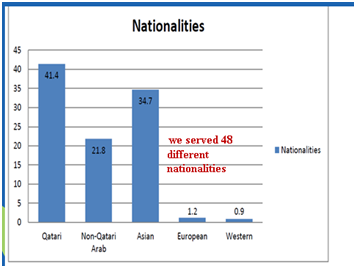

It was important to us to look into any possible variation in prescribing practices based on regional and ethnic back ground because our department provides services to more than forty different nationalities and ethnic groups. This factor is equally valid for the prescribers as well.

Across 147 studies (1,418,163 participants, 82.9% diagnosed with schizophrenia IQR=42-100%, the median APP rate was 19.6% (IQR=12.9-35.0%). Most common combinations included first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs)+second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (42.4%, IQR=0.0-71.4%) followed by FGAs+FGAs (19.6%, IQR=0.0-100%) and SGAs+SGAs (1.8%, IQR=0.0-28%). APP rates were not different between decades (1970-1979:28.8%, IQR=7.5-44%; 1980-1989:17.6%, IQR=10.8-38.2; 1990-1999:22.0%, IQR=11-40; 2000-2009:19.2% IQR=14.4-29.9, p=0.78), but between regions, being higher in Asia and Europe than North America, and in Asia than Oceania (p<0.001). APP increased numerically by 34% in North America from the 1980s 12.7%) to 2000s (17.0%) (p=0.94) and decreased significantly by 65% from 1980 (55.5%) to 2000 (19.2%) in Asia (p=0.03), with non-significant changes in Europe. APP was associated with inpatient status (p<0.001), use of FGAs (p<0.0001) and anticholinergics (<0.001), schizophrenia (p=0.01), less antidepressant use (p = 0.02), greater LAIs use (p=0.04), shorter follow-up (p=0.001) and cross-sectional vs. longitudinal study design (p=0.03). In a meta-regression, inpatient status (p<0.0001), FGA use (0.046), and schizophrenia diagnosis (p=0.004) independently predicted APP (N=66, R2=0.44, p<0.0001). Antipsychotic poly pharmacy is common practice in psychiatry.

Despite that the controlled evidence for its efficacy and safety as a strategy remains inconclusive. Moreover, antipsychotic polypharmacy was more common in schizophrenia, inpatients, adults, patients treated with decanoate formulations and with anticholinergics, and in patients treated in Asia. The number of studies reporting on rates of antipsychotic polypharmacy is in stark contrast to investigations of prescriber reasons and patient responses, data that are needed to inform clinical practice.

Tolerability of antipsychotic polypharmacy

There are relatively consistent reports of higher antipsychotic doses in patients receiving antipsychotic polypharmacy.6 Therefore, it is not surprising that antipsychotic polypharmacy has been associated with dose-related side effects at the dopamine receptor, such as hyperprolactinemia9,10 and extrapyramidal side effects that were reported either directly,11 or indirectly, expressed as hyper-salivation.10,12 or an increased use of anticholinergics.13,14 Other than that, reports about the tolerability of antipsychotic polypharmacy are limited and mostly inconclusive. In isolated reports, antipsychotic polypharmacy has been associated with increased side effects in general,15,16 sedation,9 cognitive problems,17 weight gain,18 dyslipidemia,19 glucose elevation and diabetes mellitus,20,21 metabolic syndrome,19 and cardiovascular death.22,23

In this study, the authors are set to review the prescribing practices at the department of Psychiatry, in regard to the Antipsychotic polypharmacy, and see how it compares to the international general psychiatric practice then compare it to the existing guidelines. This is a retrospective descriptive study based on electronic charts review of all admissions to the psychiatry department during a six month period of 2012; among other parameters, we have analyzed them for prescribing patterns related to polypharmacy. We recorded the diagnosis, number of prescribed anti psychotics and doses, age, sex, ethnicity and the length of stay of the patients admitted in that period. The data was collected anonymously, pooled and then studied, and analyzed using SPSS 21 statistical software program. All admissions were included and there were no exclusion criteria.

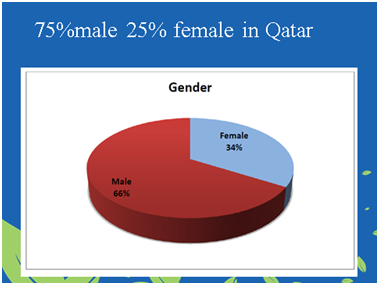

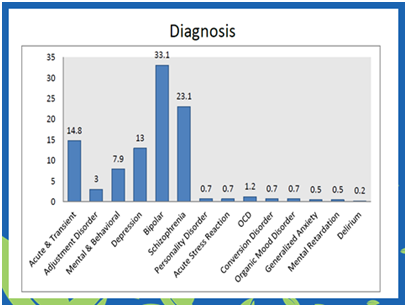

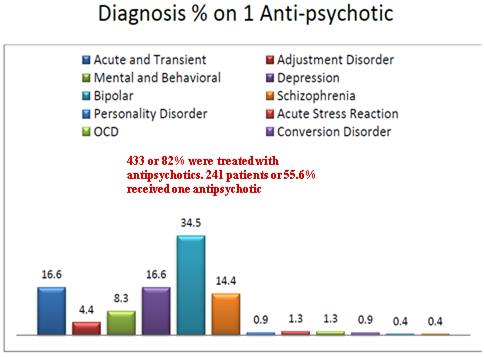

The review of 527 patient files, 33.8% female and 66.2% males (Table 1) who originated from 48 different nationalities (Table 2) with age ranging from 13years old to 77 years old and an average length of stay of 15.5 days were admitted to psychiatry (Table 3). The distribution of admitting diagnosis was peculiar for having a rather large representation of Acute and transient Psychosis mainly among the newly arrived guest workers, also that the number of bipolar disorder patients hospitalized surpassed those with schizophrenia (Table 4). 433 or 82% were prescribed antipsychotics. 241 patients or 55.6% received one antipsychotic (Table 5). While 192 patients a 44.4% received polypharmacy; of those patients 59.3% (114) received two antipsychotics (Table 6), (61) a 31.8% were given three antipsychotics). Most of those who were taking 3 antipsychotics were diagnosed as schizophrenic, being at twice the number of patients with bipolar diagnosis. The patients with acute and transient psychosis continued to be highly represented at 17% of the sample. 17 patients, an 8.9% were treated with four simultaneous antipsychotics. Here, we looked at the dosage of drugs prescribed, and in every case, each drug was in small, subtherapeutic doses(Table 7).

Table 1 That amounted to a total of 527 patients. Compared to the Qatari population, the distribution of gender was slightly skewed toward the number of female patients compared to male patients, but that was expected because globally

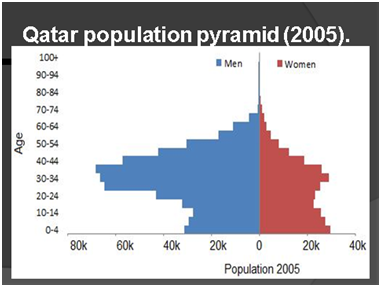

Table 2 The pyramid of population living in Qatar does not follow a normal pattern, where we have 1 female for every 3 males, and the expat working population between the ages of 20 and 45 represents the majority in both sexes

This is also congruent and reflective of our patients

Table 3 Qatar is a host to over 50 nationalities, representing different percentages of the total population. During the six months of review, we counted a service rendered to 48 different nationalities, being that the Qatari population was represented by over 41% of all inpatient services, while it represents only about 20% of the existing population

Table 4 The frequency of admitting diagnosis shows more Bipolar disorder patients admitted at a rate of 33% compared to schizophrenia at 23%. It was noticeable that the diagnosis of acute and transient psychosis reaches 15% of admissions, mostly with recently-arriving guest workers

Table 5 Out of the 527 patients who were admitted, 433 patients were on some kind of antipsychotic, which represented 82% of all admitted patients. Of those patients, 55% were prescribed one antipsychotic and 192 patients, being 44%, were on some kind of antipsychotic polypharmacy

It is clear that we do have a problem. The prevalence of anti-psychotic polypharmacy in our hospital is by far much higher than the commonly found trend in hospitals across the world where the overall mean antipsychotic polypharmacy rate was 26%;2 despite all evidence-based medicine and guidelines that do not support a systematic practice of polypharmacy and no benefit from adding another antipsychotic before reaching therapeutic level for a therapeutic length of time with the first antipsychotic, that was another trend that is not supported by literature where a second and even third anti-psychotic was prescribed before reaching a recommended and therapeutic dosage and level on the first prescribed substance, thus many patients ended receiving two, three or four subtherapeutic dosages of anti-psychotics which added the burden of cumulative side effects without any proven clinical benefit. We made a conscious effort not to look into individual practitioners prescribing habits for our goal was to find what benefits our patients.

The impact of anti-psychotic polypharmacy has been associated with increased morbid obesity, increased diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia as well as increased movement disorders and cardiac morbidity. By shedding the light on poly pharmacy practices we hope to raise the awareness of prescribers regarding the many added side effects that inflicts the patients receiving these drugs: Metabolic syndrome (Diabetes and Hyper-lipidimiea), obesity, Hypertension, increased extra pyramidal symptoms and Tardive Dyskinesia, increased cardiac morbidity.

Our aim is to use these results to raise the awareness of the prescribers about the Evidence Based Medicine and the guidelines regarding polypharmacy. One of the first steps would be implementing cyclical seminars for all psychiatric staff to educate those regarding accepted practices and approved guidelines when it comes to prescribing and monitoring antipsychotics; then, a year later, re-audit a similar number of admissions so we can measure outcome. To appoint a utilization review specialist and or a clinical pharmacist who would flag a file with polypharmacy that is lacking justifying documentation right at the start of the prescription.

Further research and audits to the level of monitoring the psychiatric patients for metabolic syndrome, cardiac changes are needed to continue to improve patient health and treatment outcome. An incidental finding was the prevalence of acute and transient psychosis which is a matter with limited data in the literature. It could be the subject of another and separate review of the profile of patients admitted or discharged with that diagnosis.

None.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2015 Zaraa, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.