Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6445

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 6

University of Leicester, UK

Correspondence: Parandaman Thechanamurthi, University of Leicester, UK

Received: March 30, 2016 | Published: May 18, 2016

Citation: Thechanamurthi P, Bull R (2016) Evaluating the "12 Steps" Programme: Relapse Reduction for Substance Dependency in Relation to Ethnicity. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry 5(6): 00313. DOI: 10.15406/jpcpy.2016.05.00313

Aim: This study investigates if the 12 steps programme reduces relapse rates for substance dependency population in Singapore.

Methods: This quantitative research study adopted a within subject times design. Psychometric tests were administered to the treatment group and the control group on five occasions; pre-test, 1st month, 2nd month, 3rd month and post-test.

Participants: This research involved two groups of participants; a treatment group (n=10) and a control group (n=10). The ethnic composition of the group consisted of Indians and Chinese from Singapore.

Findings: Measures indicated that there were some differences in scores between the treatment group and control group. For example, during the pre-test there was a difference in scores between the treatment and the control group regarding the dependent variables and except for depression, the scores did not change as a function of time, with depression only changing as a function of time from the second month.

Conclusion: The results suggest that the 12 steps programme may not be an effective treatment for the reduction of negative emotional states, social anxiety and relapse probability.

Step down care is important1,2 and could play a vital role in the substance dependent not relapsing. Miller and Caroll 3 have claimed that such aftercare forms one of the three effective areas which need to be considered when delivering substance abuse or dependence treatment.

The main aim of the current study is to examine if TSP is effective for substance dependency (SD) in Singapore.

The 12 Steps

TSP was developed in 1935 to address a wide spectrum of substance dependency by Dr Bob Smith (www.12steps.org). While originally used to help alcoholic dependents obtain and sustain sobriety, others have also found the programme to be helpful in addressing a myriad of addictive issues.4

How is 12 steps conducted?

TSP is intended to be a guide for recovery from substance dependence; the programme is not only about stopping the substance dependency process but also aids the addict in understanding the emotional and mental consequences of substance dependence. The programme has 12 suggested steps. Each step of the programme serves a different purpose and the substance dependent population is guided by a facilitator through each step. The facilitator encourages but does not force the participants to follow the steps, which is done so that the participants have a personal desire to change which could mean that the substance dependents’ probability of recovery could be higher as the willingness for recovery comes from the substance dependents themselves.

When do the 12 steps not work?

TSP is a group based self-help programme. It has a composition of many different substance dependents who come together to address their substance dependency issues. Hester and Miller5 advocated the concept of treatment matching to facilitate individual needs rather than group treatment, as in a group treatment setting not everyone would be comfortable in sharing their issues. Thus the whole essence of peer support advocated by the TSP would not be utilized. This becomes more significant when dealing with different ethnic groups who may not like sharing about their issues amongst people who may not be close kith and kin, moreover Singapore is a small country, it is highly possible to bump into each other in public places which may potentially.

Research by Caetano6 indicates that only 76% of Asian Americans have a positive inclination towards the TSP. This may be a clear indication that they may have not embraced the treatment modality due to several reasons such as association with a self-help group (which deals with substance dependency) may be viewed as a loss of self-esteem and confidence, inability to fit into the treatment due to different dynamics within the group and not being able to function within the group due to the prescribed modality of the TSP such as making amendments (step 9), acknowledging that they are powerless and that their lives have become unmanageable (step1).

Further research by Wesson et al.,7 Hall and Harvassy,8 and Peterson and Seligman9 indicates that acceptance of the addict label and the unmanageability (as reflected in step 1 of the TSP) may bring with it several negative effects such as low self-image and low self-esteem. Findings by Miller10,11 and Cox and Klinger12 tend to disagree with the 12 steps modality of acceptance of being an addict and the unmanageability that it causes has to be initiated to begin the TSP. Advocates of TSP feel that acceptance of being an addict and the unmanageability it causes is the primary step of the complex treatment process and acceptance is needed on the first step to begin the TSP. However recent advancements in psychotherapy indicate that therapeutic work can begin without acceptance. This could mean there is a probability that the rehabilitation process could be initiated through expectations of others, motivation towards substances, anger management, relapse prevention, demerits of substance dependence and looking into their triggers without acceptance of the addict label. However it is also important to view the issue from a cultural perspective where acceptance of a label especially so in a society which is governed by Asian ideals and which is not forgiving becomes a major issue for the addict, the issue of self-respect becomes a potential barrier to treatment.

Findings by Dorsman,13 Galif & Sussman14 and Kaskutas15 point out that certain ideologised aspects of TSP may not suit the substance dependents, such as the concepts of higher power, god, spirituality and substance dependence as a disease. These concepts may not be accepted by certain groups of people who attend the programme. There are four steps out of the 12 steps which contains the word god (Steps 2, 3, 5 & 6). Participants who are atheists or who may have negative experiences with religion may also find it difficult to assimilate within the group. Peele16‒18 reported that TSP maintains that substance dependence is a disease but not a medical one but a disease of eroded moral values. This concept of eroded moral values could be a major issue for people from Asian society55

What works for 12 steps programme (TSP)

Numerous studies of the TSP have shown that attendance during the 12 steps programme is associated with abstinence, improved substance use and psychological healthy outcomes.19‒21 This could be because participating in TSP provides a platform where by the treatment participants are exposed to people that could well be suffering from same problems and issues, and this could reinforce the belief that the individual is not the only one suffering from the substance dependence. Moreover, since TSP is facilitated by a person who is a recovering substance dependent, it also exposes the treatment participants to a role model which the treatment population could take strength from and could aid the treatment participants in their recovery process. However the facilitator may not be therapeutically trained to run the TSP like a clinical therapy group. Thus there may be possibilities that the facilitator may not be able to handle clinical issues present within the group, for example a depressed member or a member who manifests with social anxiety. However, Evans & Sullivan22 found that substance abuse co-occurring with mental illness is a chronic problem that requires long term structured help. It was felt that the TSP will be able to provide the structure that is needed for this particular population. TSP encourages personal growth like abstinence from substance usage and good psychological functioning through supportive social networks within the group. Humphreys19 found that association with TSP for substance dependents with dual disorders would help with long term remission of mental disorders. This could be because this population would be able to form close relationships with other peers within the twelve steps programme and may be able to share their issues with these new friends. The friends support may help them stabilize their psychiatric symptoms. Chi et al.,23 noted that dual diagnosed dependents form a close link to the twelve steps programme and benefit from participating in the programme probably due to strong supportive networks. Moos et al.,24 found that attending TSP was associated with less severe distress and fewer psychiatric symptoms and more stable behaviour at a one year follow up. However previous studies by Blau25 and Timko & Moss26 fail to support this claim. It is interesting to observe that older research findings contradict the findings of recent research.19,22 It may be that some TSP groups are more effective, expressive and aggressive.2,27 Another possibility could be due to differing dynamics, personalities and family backgrounds that may be present within different groups which may impede or facilitate the therapeutic process. Different facilitators may exhibit different approaches, as such though the steps and modality of TSP remains the same, the delivery may be different.

The TSP has been recognized as, important to the system of care and rehabilitation for substance dependent population, by being able to provide continued support of care and structure, TSP has reduced the rates of post treatment relapse and subsequent treatment utilization.28 This could be because TSP is accessible to anyone who has the desire to recover from addiction, other principles such as anonymity within the group, a support link that is linked worldwide, being exposed to positive peer influence could be possible reasons to reduction in rates of post treatment relapse and subsequent treatment utilization. This latter finding is important as it supports the notion that being surrounded by a group of people who are non-drug using peers gives the TSP attendees’ role models whom they could identify with and also increases the confidence amongst the TSP attendees that recovery is attainable. It also places them away from their old peers who were drug users which ultimately improves outcomes in terms of drug usage due to avoidance of drug using peers. Through TSP there is a structure to the “recovery addiction process” and the substance dependent population within the group would understand the addiction problem through personal experiences.

However there has been a lack of relevant literature on the number of substance dependents who have dropped out of the programme and could have relapsed. As such the current results provided in various researches could only be examining substance dependents who may have self-selected themselves into TSP which could provide a link to the positive numbers citied in various researches on the success of the 12 steps programme.19,20

Cultural, racial and ethnic subgroups

There has been very little research on involvement in TSP regarding ethnic and racial sub groups. Data that were extracted by Caetano from a national survey showed that in general, Hispanics (97%), African Americans (87%) and whites (94%) had positive views of TSP which actually means that these groups could recommend TSP over other treatment programmes such as CBT intervention or even counselling. A reason towards this positive inclination could have been due to substance dependent people from their own ethnic groups could have gone through TSP with positive outcome, plus the non-availability of professional treatment centres.29 Even though the above mentioned ethnic groups had positive inclination towards TSP, only 76% of Asian Americans recommended TSP as a treatment modality. The fact that the Asian Americans had the lowest inclination towards the TSP, could be attributed to many reasons such as participating in TSP could expose “the family secret” that someone in the family is having substance dependency issues, which could contribute to the shaming of the family. Another reason could be that the substance dependent would have to acknowledge that he or she is powerless over the substance dependency which could indicate a lack of power amongst the Asian mentality, thus their lack of positive inclination towards TSP.

Cultural aspects of each ethnicity in Singapore

It is important that when a treatment programme is being introduced, it takes the cultural aspect of the patients into account. As stated by Amodeo & Jones,30 culture and substance use interact and shape each other. This could be because for some ethnic groups, consuming drugs and alcohol may be part of their culture and thus it is necessary to have culture in mind when introducing a treatment programme. Thus research concerning the South East Asian Diasporas could play a role regarding treatment programmes that could be rolled out for substance dependent populations in Singapore.

Chinese Community

Amongst the Chinese community in Singapore it is accepted that gambling is a family activity; it is common to come across family members gambling during funeral wakes, wedding ceremonies and so on. When a family member accumulates heavy debts, it is common practice for the rest of the family to “bail” him out and not allow the little “family secret” to leak out as that would mean “losing face”. When working with this type of population there is a need to be able to appreciate this ideology when rolling out a treatment programme.

Just as how members of the Chinese community are sensitive to certain traits and exhibit certain characteristics that are unique to their community the Malay and Indian communities also exhibit uniqueness.

Malay Community

It is common knowledge that the Malay community live within a set of rules and regulations which they abide by strictly. Drug dependency is common among people from this ethnicity. When identifying motivation to change it is important to appreciate the Malay’s belief system and balance of hierarchical powers. Members of this community have a deep inclination towards spiritual appreciation and as such it would be good if the treatment modality for this substance dependent ethnic population has a form of spiritual concept or component to it. Then Home Affairs Minister Wong Kan Seng in 1994 noted that the higher rate of drug usage amongst this population is due to lax family supervision and the gregarious nature of drug taking amongst the community.

Indian community

A large number of alcoholic dependent people in Singapore are Indians. This trend is evident especially amongst the younger age group and women. The National Health Survey (NHS) conducted in 2004 revealed that alcohol dependence among Singapore residents aged 18 to 69years. The Indian population measured 2.7% of the 6.3% residents with high alcohol dependency rates. Indians are a highly protective group of people and prefer denial to avoid the issue of addiction in the family as such resistance to change would be high as it may be an embarrassment to the family.

The TSP modality of treatment may have included some ideologies that may not have been part of the major ethnic groups in Singapore, for example a spiritual component may not be relevant to participants who are atheists. There is also a need for the substance dependent person to make “direct amends” to people whom they have harmed when they were under the influence of substance, which might be an issue due to the concept of “losing face“. As such there is the need to evaluate the suitability of TSP for substance dependent population in Singapore

Hypotheses

TSP is associated with abstinence, improved substance use and psychological healthy outcomes.19‒21 The hypotheses here are that attendance adherence to the TSP would

(i) Reduce the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, stress

(ii) Lower levels of social anxiety and

(iii) Lower the relapse rate.

This quantitative research study adopted a within subject time series design. The study lasted about four months. There was periodical administration of tests at monthly intervals.

The program was conducted over three months and was conducted by the same facilitator who was a recovering substance dependent person. This was done to ensure that the delivery of the programme is consistent throughout the three months. During the three months each week will be focused on one of the 12 steps, for example, in week 1 the treatment group will focus on Step 1, in week2 they will focus on Step 2. There will be a group discussion based on the topic at the end of the lesson. That participating population were undergoing residential treatment meant that there would not be any form of external influence outside the halfway house setting on the participants.

Participants

The population was identified from Highpoint Community Services (HCS) (www.highpoint.org.sg). HCS is a halfway house which operates an in house rehabilitation service for ex-incarcerated male offenders who are substance dependent. The population was based on two ethnicities Chinese and Indian. Malays were not included because they were based in a different halfway house due to their religious background. Selection was based on random sampling. The assistant directors from Highpoint choose the participants for both the treatment as well as the control group. The sampling criteria were

(i) Substance dependent people who are Chinese or Indian by ethnicity

(ii) Males from eighteen to sixty years of age

(iii) Dependents who have been in the halfway house for a minimum period of three months

(iv) Not been through TSP.

The participants for the control and treatment group were selected using the simple random sampling method. Participants who fulfilled the above mentioned sampling criteria were chosen randomly by the assistant director. Participants who satisfied the sampling criteria were drawn out of the box and were further divided between “Treatment group” and “Control group”. The mean age for treatment group (M= 41.5, SD 10.23); control group (M=37.7, SD=10.98).

Control group

The participants from the control group were also from two ethnicities Chinese and Indian. They were matched to the treatment group as per inclusion criteria. During the whole process of the research, the control group was based in the halfway house. When the TSP was being conducted the control group were brought to the library in the halfway house so that there would be no form of exposure to the programme. The control group participants were also based in a different dormitory from the participants in the treatment group to prevent any form of information of the programme being passed.

Three psychometric tools were used to evaluate the efficacy of the programme.

Advance Warning of Relapse (Appendix A,B)

The Advance Warning of Relapse (AWARE) questionnaire was used to identify warnings signs of relapse and was administered pre and post program and at periodic intervals when TSP was being conducted. The questionnaire has 28 questions and each participant had to circle a 1 to 7 rating scale in respect to each question. The questions are arranged in the order of occurrence of warning signs, as hypothesized by Gorski.31

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Appendix C)

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) is a measure of emotional states with three self-report scale components which are designed to measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress. The shorter version was used for this research.

Social Avoidance Distress Scale (Appendix D)

The Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (SADS) measures anxiety via four sub- scales - distress, discomfort fear, anxiety and the avoidance of social situations (Friend, 1969). The SADS has scored an internal consistency at .94 and the test reliability score ranges from .68.32

Baseline self-report psychometric tests were administered two weeks prior to the start of TSP. The psychometric tests were re-administered on the last week of the first month second and the third month of the programme. The post test was administered two weeks after TSP had finished. Each participant was given 20minutes to complete each test and with five minutes break in between each test for the participants to rest.

Participation in the research was voluntary not mandatory. Permission was sought with HCS Assistant Director of Social Services. “Confidentiality” was maintained unless suicide ideation or any form of harm towards participant’s life became evident, where the information would be relayed to the Assistant Director.

In total there were five dependent variables (depression, anxiety, stress, sads and aware). Mixed analysis of variance (A NOVA) was conducted for each of the scores across five time periods (Pre-test, First Month, Second Month, Third Month and Post-test). Mean and standard deviation values are presented in Table 1.

|

Intervention |

Control |

||||

|

Time Period |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

|

|

Depression |

Pre-test |

10.4 |

10.49 |

26 |

12.58 |

|

1st month |

8.6 |

4.99 |

20.7 |

13.06 |

|

|

2nd month |

11.8 |

6.76 |

27.2 |

11.93 |

|

|

3rd month |

10.2 |

8.4 |

21.2 |

10.96 |

|

|

Post-test |

9 |

8.65 |

17.8 |

10.93 |

|

|

Anxiety |

Pre-test |

11.4 |

9.14 |

22.4 |

8.47 |

|

1st month |

8.2 |

6.36 |

18 |

7.3 |

|

|

2nd month |

9 |

9.72 |

17 |

8.29 |

|

|

3rd month |

6.4 |

6.31 |

18.8 |

9.94 |

|

|

Post-test |

6.6 |

9.85 |

17.6 |

8.73 |

|

|

Stress |

Pre-test |

9.2 |

9.25 |

23.8 |

7.97 |

|

1st month |

6.6 |

8.69 |

23 |

9.25 |

|

|

2nd month |

8.8 |

9.94 |

21.4 |

10.79 |

|

|

3rd month |

5.8 |

7.45 |

23.2 |

9.85 |

|

|

Post-test |

6 |

6.8 |

19.6 |

12.54 |

|

|

SADS |

Pre-test |

8.9 |

6.47 |

18.9 |

7.84 |

|

1st month |

7.3 |

7.05 |

16.2 |

8.84 |

|

|

2nd month |

9 |

8.99 |

17 |

8.63 |

|

|

3rd month |

6.7 |

6.6 |

15.5 |

9.25 |

|

|

Post-test |

8.1 |

6.2 |

11.5 |

8.32 |

|

|

AWARE |

Pre-test |

78.3 |

23.35 |

114.7 |

33.94 |

|

1st month |

80.4 |

16.27 |

115.3 |

36.45 |

|

|

2nd month |

76.8 |

14.11 |

115.7 |

31.7 |

|

|

3rd month |

78.4 |

20.58 |

104.1 |

34.08 |

|

|

Post-test |

74.6 |

19.64 |

99.8 |

40.23 |

|

Table 1 Mean and standard deviation values of scores for Intervention and control groups

nIntervention = 10, nControl = 10

At the beginning of the study the scores in the intervention group were already lower than the control group. There could be several reasons for this such as external positive influences away from the halfway house such as family reunion or family visits that could have made an impact on the treatment group which could have made the treatment group’s scores lower than the control group. The treatment group knowing that they would be enrolled into TSP, could have expected that being enrolled into the programme would help fight their addiction issues and therefore may have thought that their quest to fight the dependence issue would be easier through attending TSP

Depression

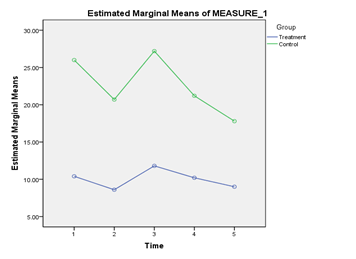

There was a significant main effect for Time, Wilks’ Lambda = .29, F(4,15) = 9.0, p = .001, Partial Eta squared = .71. For Depression scores, there was no significant interaction between Intervention and Time, Wilks’ Lambda = .56, F(4,15) = 2.93, p = .057, Partial Eta squared = .44. Further pair wise comparisons showed a significant decrease in Depression scores at a p <.05 level from the Second Month (M = 19.5, SE = 2.17) to the Post-test period (M = 13.4, SE = 2.21). The main effect comparing Intervention and Control groups was also significant, F(1,18) = 10.72, p = .004, Partial Eta squared = .37. Pair wise comparisons indicate that the Intervention Group (M = 10.0, SE = 2.72) had significantly lower Depression scores than the Control Group (M = 22.58, SE = 2.72); p < .0 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Presents the Depression scores obtained by the treatment group and the control group from the period of pre-test till post-test.

Anxiety

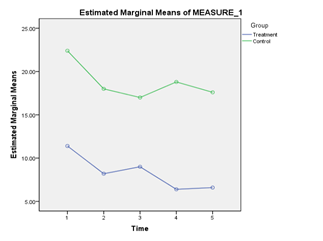

For Anxiety scores, there was no significant interaction between Intervention and Time, Wilks’ Lambda = .77, F(4,15) = 1.10, p = .39, Partial Eta squared = .23. There was also no significant main effect of Time, Wilks’ Lambda = .59, F (4,15) = 2.63, p = .076, Partial Eta squared = .41. The main effect comparing Intervention and Control groups was significant, F(1,18) = 10.58, p = .004, Partial Eta squared = .37. Pair wise comparisons indicate that the Intervention Group (M = 8.32, SE = 2.27) had significantly lower Anxiety scores than the Control Group (M = 18.76, SE = 2.27); p < .01 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Presents the Anxiety scores obtained by the treatment group and the control group from the period of pre-test till post-test.

Stress

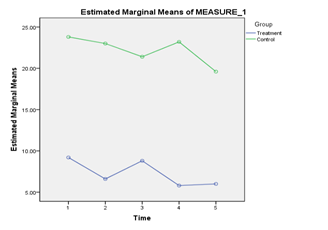

There was no significant interaction between Intervention and Time for Stress scores, Wilks’ Lambda = .80, F(4,15) = .94, p = .47, Partial Eta squared = .20. There was also no significant main effect of Time, Wilks’ Lambda = .86, F(4,15) = .63, p = .65, Partial Eta squared = .14. There was a significant main effect of Intervention, F(1,18) = 18.94, p < .001, Partial Eta squared = .51. Pair wise comparisons indicate that the Intervention Group (M = 7.28, SE = 2.42) had significantly lower Stress scores than the Control Group (M = 22.2, SE = 2.42); p < .001 (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Presents the Stress scores obtained by the treatment group and the control group from the period of pre-test till post-test.

Sads

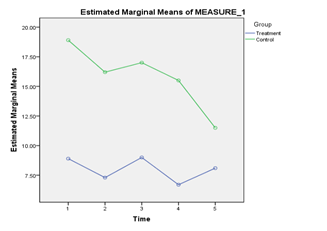

For the SADS scores, no significant interaction was found between Intervention and Time, Wilks’ Lambda = .76, F (4,15) = 1.19, p = .36, Partial Eta squared = .24. There was also no significant main effect of Time, Wilks’ Lambda = .69, F(4,15) = 1.72, p = .20, Partial Eta squared = .31. There was a significant main effect of Intervention, F(1,18) = 8.33, p =.01, Partial Eta squared = .32. Pair wise comparisons indicate that the Intervention Group (M = 8.0, SE = 1.92) had significantly lower SADS scores than the Control Group (M = 15.82, SE = 1.92); p <.05 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Presents the SADS scores obtained by the treatment group and the control group from the period of pre-test till post-test.

Aware

For the AWARE scores, there was no significant main effect of Time, Wilks’ Lambda = .74, F(4,15) = 1.34, p = .30, Partial Eta squared = .26. There was a significant main effect of group, F(1,18) = 9.03, p =.008, Partial Eta squared = .33. Pair wise comparisons indicate that the Intervention Group (M = 77.7, SE = 7.58) had significantly lower AWARE scores than the Control Group (M = 109.92, SE = 7.58); p <.01. No significant interaction was found between group and Time as well, Wilks’ Lambda = .82, F(4,15) = .80, p = .54, Partial Eta squared = .18 (Figure 5).

Overall the results indicate that the hypotheses , that TSP would lower negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, stress; lower levels of social anxiety and lastly lower the relapse probability has not been supported.

How do the current findings fit with the previous literature?

Much of the relevant literature has been focused on families of white middle class males (Steven & Smith, 2007) which could explain why the present study which focused on Asian population may be difficult to correlate with the prior research. This research examined the four factors, depression, anxiety, social anxiety and relapse probability. Some of the prior research reviewed was admitted with relaxed criteria but the articles did include components of these four factors.

While traditional TSP participation has been found to be beneficial for substance dependents,19‒21 it may be beneficial for substance dependents (who may also suffer from a psychiatric comorbidity) to attend a more appropriate programme that may address such psychiatric symptoms as well. Substance dependents who manifest psychiatric disorders have high rates of post treatment relapse and additional episodes of psychiatric treatment.33 In comparison with the current research study there is no significant main effect of time for depression, social anxiety, anxiety and relapse probability(pre-test versus post-test). It could be noted that participants from the treatment group may not have had any form of direct benefit from attending TSP. Scores of depression, social anxiety, anxiety and relapse probability did not improve over the treatment period. In fact the measures were fluctuating from pre-test to post which may indicate that the participants were not stable when attending TSP.

Wesson et al.,7 Hall et al.,8 Peterson et al.,9 and Beck et al.,34 findings indicate that acceptance of addict label and unmanageability (step1) may contribute to low self-esteem, undue stress and low self-image. The first step of TSP could be a destabilizing factor for many addicts as it requires the addict to admit that they are powerless over their addiction and that their lives have become unmanageable (step 1). This could result in harmful consequences such as developing depression, losing social support within the group who support step 1. They may also find it difficult communicating with the facilitator due to differing belief systems. The facilitator who would be a recovering person would be ingrained with TSP principals as such when TSP participants resist conforming to TSP steps, facilitators may use confrontation to achieve acceptance and decrease denial.35 This may be counterproductive as change should be innate personal process initiated by the participant not the facilitator.

Jordan et al.,36 noted that substance dependents who suffer from dual disorders tend deny and minimize their substance use. This makes them unworthy candidates of the TSP, as without owning up to their substance usage and the unmanageability it causes, they would not be able to progress through the TSP and may reduce their confidence in TSP which might affect their motivation levels of progressing through the TSP. As such there is a possibility that the treatment group might have encountered the same issues which could have caused the measure to fluctuate. This could be an indication that the group was not functioning well together and was not responding to the TSP. However one cannot ascertain if the non-functionality of the group is due to the facilitator or the denial the participants might have shown during certain steps which might have impeded their progress and stopped them from achieving positive results.

It was reflected by Wibrodt et al., Christine et al.,37 that there was an increase in abstinence rates only for participants who had attended substantial amount of TSP and those who had a sponsor to guide them. In comparison the current study did not provide the same form of stimulating environment that a TSP would provide. In a traditional setting of TSP, it would be filled with a number of recovering addicts who would be able to guide the newly inducted members. The members would also act as mentors traditionally known as “sponsors”. The sponsors would be able to give individual attention and would be available at all times. The sponsors would be able to manage expectations and provide supportive social networks, this may encourage personal growth that recovery is attainable. The only recovery person that the treatment group had access to, during this research was the facilitator. Thus there was limited good peer influence and support system when compared to normal TSP. Amodeo et al.,30 hypothesized that culture and substance interact and shape each other. The facilitator was a white American and there could be an issue of cultural barrier. He may not have understood the cultural sensitivity present amongst the participants. Montgomery et al.,27 Tonigan et al.,2 felt that some TSP groups may be more effective due to how the whole process is being facilitated and this may impede or facilitate the therapeutic process within the group. As such, future research could focus on setting up a more traditional TSP group with few recovering addicts who understand the local culture to facilitate the TSP which may result in better measures.

Spirituality is an important component of TSP, but spirituality and being associated with god may vary among individuals due to different beliefs and ethnicity, Caetano, 1983 found that only 76% of Asian Americans frequent TSP. Chen33 suggested that spirituality plays a significant role as it gives the group more stable and beneficial outcomes in terms of mental health. There are four steps in TSP that contains the word god, participants who may be atheists or who may have bad experiences with spirituality may not feel comfortable. Since the current research sample focused on Indians and Chinese in Singapore, there is likelihood that not all members of the group may have embraced the TSP, due to cultural insensitivity and belief systems. The issue of asking god to remove all defects of character (step 6); admitting to god the exact nature of wrongs done may not gel well within the group. This could be due to difficulty in accepting and trusting the idea of god due to unpleasant experiences in the past, forcing them to agree that they have a moral disease due to eroded moral values could reduce their sense of empowerment and self-esteem.16,17

The shame based model that TSP employs is outdated and potentially harmful as it may exacerbate psychiatric conditions or even revive painful memories and may cause the participants to relapse. The steps discussed above go on to justify that the participants are full of character defects even though substance dependence is a This may prevent them from getting desirable treatment outcomes.38 Treatment for substance dependents should be empowering, safe and non-judgemental environment and group therapy should incalucate skills in order for the participants to achieve insight and leave the group. However TSP states that addicts will never recover from this moral disease17 and need lifelong commitment to God despite empirical evidenced research stating that substance dependence is a physiological disease which alters brain chemistry,39 instead of empowering the participants, being enrolled in TSP could be counterproductive as it could be emotionally demoralising when participants here these comments which may prevent them from achieving optimal effect from attending TSP. This may have contributed to the non-significant main effect for anxiety, social anxiety, relapse probability and depression to a certain extent as one is not able to ascertain if the significant effect of time for depression occurred because of TSP or due to other external variables.

Limitations in the current research

There was a control group that was abstinent from substance from pre-test to post-test but the control group did not go through any type of therapeutic programme. It would be good if a comparison group were made to go through a therapeutic programme. Then it would be easier to compare if there was a main effect of the intervention between TSP and the other therapeutic programme.

The second limitation of the study is that it examined whether TSP to reduced negative emotional states, social anxiety and relapse probability. It is understood that negative emotional states and social anxiety may need pharmacological intervention on top of therapeutic group intervention. Being involved in the 12 steps programme may not effectively treat the issues as the 12 steps programme is primarily an addiction treatment programme. Thus instead of looking at negative emotional states and other psychological issues, issues pertaining to addiction, such as increased level of resilience, increased level of motivation to change and abstinence from substance abuse could be examined. This would make it more addiction specific and that is something within what TSP is designed to do.

Overall, the results from this study suggest that TSP may not be an useful approach in reducing dependents’ negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, stress, social anxiety and relapse probability rate. While the fact that the treatment group have had significantly better scores may initially seem like the intervention is working, analysis of the differences causing the significant results show that even at pre- test, the scores in the intervention group were already lower than the control group.

The lack of significant interaction effects showed that the scores did not change as a function of time. Hence, the results do not support the hypotheses.

None.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2016 Thechanamurthi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.