Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6445

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 6

Department of Educational Psychology, Minia University, Egypt

Correspondence: Sabry M Abd-El-Fattah, Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, Minia University, Minia City, Egypt

Received: October 08, 2018 | Published: November 9, 2018

Citation: Abd-El-Fattah SM. Emotional intelligence within the framework of the ability model: A nomological network analysis of a situational judgment test. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry. 2018;9(6):552?565. DOI: 10.15406/jpcpy.2018.09.00589

This study utilized a nomological network analysis approach to empirically validate the Arabic version of the Situational Judgment Test of Emotional Intelligence (SJTEI-AR). A nomological network analysis includes a within-network and a between-network construct validation. The sample of the study consisted of 236 Egyptian undergraduates. The within-network construct validation confirmed the multidimensionality of the SJTEI-AR. The three correlated factor model of the SJTEI-AR fit the data better than the one factor model and the hierarchical model and it was invariant across gender. Females scored significantly higher than males on the utilizing own emotion factor of the SJTEI-AR. The between-network construct validation showed that the SJTEI-AR significantly predicted academic achievement and personality dimensions. The predictability of the SJTEI-AR was evident by significantly predicting academic achievement after taking into account the effect of gender and personality dimensions.

Keywords: emotional intelligence, ability model, situational judgment test, nomological network analysis, personality dimensions, academic achievement

The concept of emotional intelligence first appeared in Michael Beldoch’s writings in 1964, but Daniel Goleman's 1995 book "Emotional Intelligence: Why Is It More Important than IQ" has made it popular. Goleman1 has presented the notion that the experience and expression of emotions is a domain of intelligence and has developed the construct of emotional intelligence to include several social and communications skills that are guided by the understanding of emotional expressions.2 Currently, there are several well-established models with alternate theoretical frameworks for conceptualizing and understanding the nature of emotional intelligence. One of these models is the ability model, also known as the cognitive-emotion ability model Salovey et al.3 developed the ability model that places emotional intelligence within the domain of intelligence where emotions and thought can interact together adaptively. The model emphasizes an individual’s skills to recognize emotional information and perform abstract reasoning using this information. According to the ability model, emotional intelligence refers to the ability to perceive, appraise, and express emotions precisely and adaptively, together with the ability to understand and conceptualize emotional knowledge, access, generate, and use emotions to assist and facilitate thought, and regulate emotions in oneself and others to promote emotional and intellectual growth.3,4

The ability model emphasizes four abilities of emotional intelligence:

Situational judgment tests

A situational judgment test (SJT) is a type of psychological tests that presents examinees with a variety of real-life hypothetical situations and possible responses to these situations. The SJT is described as low-fidelity stimuli because it does not require an examinee to perform actual behaviors or take real actions, and also the examinee is not observed or evaluated by trained evaluators.7 A SJT has three main components: (1) the scenario (stem), (2) the response instructions, and (3) the response forma.7,8

The situational judgment test of emotional intelligence (SJTEI)

Lievens and Chan19 suggested that the SJTs have high levels of ecological validity because SJTs require participants to respond to a variety of real-life hypothetical situations presented in different formats and therefore they are one of the most realistic ways to measure emotional intelligence. Researchers have also developed several SJT-based measures of emotional intelligence such as the Situational Test of Emotional Understanding (STEU) and the Situational Test of Emotion Management (STEM),10 each measures one component of emotional intelligence within the framework of the ability model. In addition, Bedwell & Chuah11 tested a situational judgment of emotional intelligence based on video technique.

More recently, Sharma et al.12 conducted a series of studies with samples from India to develop the Situational Judgment Test of Emotional Intelligence (SJTEI) within the framework of the ability model. An exploratory factor analysis with principal components and oblique rotation of data obtained from a heterogeneous sample (N=213) showed that the construct of emotional intelligence can be measured with 46items distributed over three factors. The first factor is utilizing own emotion (16items) which measures the ability to have perseverance and persuasion skills to respond appropriately to the setbacks of failure, communicate with people, and have intuition, commitment, determination, and confidence. The second factor is sensing others’ emotion (18items) which measures the individual's ability to recognize the emotions of others and adapt accordingly, and to be sympathetic, understanding, and friendly. The third factor understands of the emotional context (12items) which measures the individual's ability to understand the context in which emotions are expressed. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed that the 46 item, three correlated factor model of the SJTEI fit the data adequately. Another CFA with a sample of undergraduates (N=147) showed that the 46 item, three correlated factor model of the SJTEI fit the data more adequately than a 46items, one factor model and a hierarchical model (a 46 three factor model with a general model of emotional intelligence).

Several studies have examined the factorial structure of the SJTEI mainly within a Western context. For example, Shinder13 examined the factorial structure of the SJTEI using a sample of 200 students in a local college in London. An exploratory factor analysis with principal components and oblique rotations replicated the three factors posted by Sharma and his colleagues.12 A CFA showed that a 44 item, three correlated factor model fit the data adequately after deleting two items from the sensing others’ emotion subscale. The analysis also showed that the 44 item, three correlated factor model achieved a better fit to the data than the hierarchical model and the one factor model. A multigroup CFA demonstrated that the SJTEI was fully invariant across gender. Aellwing14 administered the SJTEI to a sample of 175 undergraduates in a Southwestern university in German. A CFA showed that a 46 item, three correlated factor model of the SJTEI fit the data adequately. However, the analysis further demonstrated that hierarchical model of the SJTEI achieved a better fit to the data than a three correlated factor model and a one factor model. Allowing cross-validated the hierarchical model using another sample of 162 undergraduates.

Wallbott15 using a sample of undergraduates in Italy (N=190) reported that a CFA showed that a 44items, three correlated factor model of the SJTEI fit the data adequately after deleting twoitems from the utilizing own emotion subscale. The analysis further demonstrated that a hierarchical model of the SJTEI achieved a better fit to the data than the 44 item, three correlated factor model and the one factor model. King16 analyzed data from a sample of 190 college students in Switzerland by means of CFA and reported that a 46items, three correlated factor model of the SJTEI fit the data adequately. The analysis further demonstrated that a 46 item, three correlated factor model achieved a better fit the data than the hierarchical model and the one factor model. King found the three correlated factor model of the SJTEI to be partially invariant across gender.

Gender differences in emotional intelligence

Research evidence regarding gender differences in emotional intelligence as measured by the SJTEI has been largely inconsistent. In their original study of the SJTEI, Sharma and his colleagues12 found significant mean differences between males and females in the three factors of the SJTEI favoring females. In contrast, Aellwing14 reported significant mean differences between males and females in the three factors of SJTEI favoring males. Shinder13 found significant mean differences between males and females in sensing others’ emotion and understanding of the emotional context favoring females. Wallbott15 reported a significant mean difference between male and females only the utilizing own emotion factor favoring females. King16 demonstrated nonsignificant mean differences between males and females in the three factors of the SJTEI.

Emotional intelligence and academic achievement

In their original study of the SJTEI, Sharma and his colleagues12 found significant correlation coefficients that ranged from .20 to .23 between academic achievement and the three factors of the SJTEI. Shinder13 reported significant correlation coefficients that ranged from .31 to .37 between academic achievement and the three factors of SJTEI. Aellwing14 found that the three factors of the SJTEI significantly predicted academic achievement even after controlling for the effect of students’ gender and self-esteem, and that understanding of the emotional context was the strongest predictor of academic achievement followed by the sensing others’ emotion and the utilizing own emotion respectively. Wallbott15 using path analysis technique, showed that the three factors of SJTEI have direct effects on academic achievement and that the utilizing own emotion has the strongest effect on academic achievement followed by the understanding of the emotional context and the sensing others’ emotion respectively. The three factors were found to have an indirect effect on academic achievement through academic adjustment. King16 reported significant correlation coefficients that ranged from .28 to .35 between academic achievement and the three factors of the SJTEI after partial ling out the variance due to academic engagement.

Emotional intelligence and personality dimensions

Three studies have examined the relationship between emotional intelligence as measured by the SJTEI and personality dimensions. The original study by Sharma and his colleagues12 reported that there were no significant correlation coefficients between the three factors of SJTEI and the Big Five personality dimensions with values ranging from -.002 to -.018 (p>.05). One exception is the significant correlation between utilizing own emotions and agreeableness (r=-.18, p<.01). Shinder13 reported that the correlation coefficients between the three factors of the SJTEI and the Big Five personality dimensions were no significant with values ranging from .07 to .10 (p>.05) even after controlling for the effect of students’ gender and academic specialization. Wallbott15 reported that all correlation coefficients between the three factors of the SJTEI and the Big Five personality dimensions were no significant with values ranging from .04 to .11 (p>.05) even after controlling for the effect of students’ gender.

Problem and rationale of the study

Psychologists recognize the role of culture in shaping human behavior. Thus, there have been several calls over the last fewyears for researchers within the field of psychological measurement to be alerted and sensitive to the effect of cultural context on the assessment of psychological constructs.17 The contribution of culture variation in shaping and construing human behavior becomes more imperative for the study of emotional intelligence because emotional intelligence is defined by cultural norms and values and thus culture can be seen as an antecedent of emotional intelligence. Individuals with high emotional intelligence can code and decode their own and others' emotions as they are expressed in various social situations within a specific culture. For many researchers, emotions are not universal or a biologically-based construct. Emotions are guided by the environment, and therefore there are distinct cultural differences in several aspects of emotions. Furthermore, the cultural context controls and guides how emotions are felt, expressed and displayed, recognized, interpreted, communicated, and evaluated in a social situation.18

Furthermore, we know little about emotional intelligence among native Egyptian students as described by the ability model because the number of studies conducted is limited for two reasons. Firstly, there has been a lack of Arabic language measures that are psychometrically sound and that can be used to measure emotional intelligence under the umbrella of the ability model. Most of studies on native Egyptian students have used Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test19 although this measure is somewhat problematic in terms of its validity and reliability. Secondly, Egyptian students are not competent enough in English to respond to English language measures of emotional intelligence. Thus, there is a lack of easily applicable and psychometrically sound measures of emotional intelligence within the scope of the ability model to be used with Arabic-speaking participants in Egypt. It is important to note that the scarcity of these Arabic language measures can have significant implications. Firstly, there is a lack of normative data on emotional intelligence among Egyptian students that can facilitate their clinical assessment. Secondly, Egyptian students’ responses to any measurement emotional intelligence that is not written in Arabic may result in several psychometric problems such as differences in construct conceptualization and item understanding and interpretation, and responses bias. Thirdly, it will not be possible to make reliable comparisons among participants across cultures or within certain cultures regarding emotional intelligence if different measures are operated in each culture or if there is a lack of standardized measures of emotional intelligence. On the contrary, the availability of such Arabic language measures of emotional intelligence is useful for providing information about emotional intelligence and for facilitating and promoting research on emotional intelligence among Egyptian students. In line with this argument and given the various effects of culture on individuals’ emotions, the problem being addressed in the present study concerning the validation of the SJTEI in a sample of undergraduates in Egypt. The SJTEI was originally developed using samples from India which represents an Asian culture and it has been validated with samples from several Western countries including England, German, Italy, and Switzerland. However, Egypt represents an Arabic Middle Eastern culture and thus the validity of the SJTEI needs to be further examined within an Egyptian context before it is used to measure emotional intelligence among Egyptian undergraduates because it is possible that instruments developed and validated within both Asian and Western contexts might not work properly in an Arabic Middle Eastern setting due to cultural differences.

The present study; therefore utilizes a nomological network analysis technique to empirically tackle this research problem. The term “nomological” is derived from Greek and means “lawful” or “Philosophy of science”. The nomological network approach was originally developed by Cronbach LJ20 who argued that this type of analysis is used mainly to establish measure construct validity. A construct validation approach utilizes both within- network and between-network constructs validation. Within network construct validation explores the internal structure of a construct by employing statistical techniques such as exploratory factor analysis, CFA, factorial-invariance, and reliability analyses. The between-network construct validation explores the patterns of relationships between the construct and other theoretically related constructs by applying statistical techniques such as correlation, regression, or path analysis modeling.

Questions of the study

The present study intends to answer the following research questions:

Aims of the study

The aim of the present study is twofold:

Significance of the study

Participants

A final total sample of 236 fourth year undergraduates (122 males and 114 females) participated in the present study. Students were enrolled in different academic programs at a Faculty of Education in a public university in Upper Egypt. The mean of students’ ages were 21.29 (SD=.71) and 20.84 (SD=.58) for boys and girls, respectively. Only students with complete data were retained for the present study. The percentage of students who had incomplete data was less than 3% and they were dropped from the sample. Those students failed to complete all theitems of the measurements of the present study. The analysis of demographic data showed that 97% of the students belonged to the working and lower classes.

Measurements

The Situational Judgment Test of Emotional Intelligence (SJTEI)

Sharma and his colleagues12 developed the SJTEI to measure emotional intelligence within the framework of the ability model using a situational judgment test approach. Their original sample (N=213) included people with different careers such as teachers, university students, doctors, managers, service providers, and housewives. The SJTEI consisted of 46items distributed over three factors. The first factor is utilizing own emotion (16items). This factor measures the ability to have perseverance and persuasion skills to respond appropriately to the setbacks of failure, communicate with people, and have intuition, commitment, determination, and confidence. The second factor is sensing others’ emotion (18items). This factor measures the ability to recognize others’ emotions and adapt accordingly, and to be sympathetic, understanding, and friendly. The third factor understands of the emotional context (12items). This factor measures the ability to understand the context in which emotions are expressed. Each item in the SJTEI consisted of a scenario that describes a general hypothetical real-life situation followed by three response options; each describes a possible reaction to the described situation (e.g., When you go to a slum, you see some children who cannot go to school because of poverty. (A) You will feel sad and you can experience it and try to help them, (B) You are not aware of your emotions when you see them, but will try to help them, and (C) You feel indifferent and just think that you cannot help them). Students respond to each item by responding to each of the three response options on Least-Most Preferred rating scale. A score of 1 is assigned to the Least Preferred and it means that this action is likely to make the situation worse. A score of 3 is assigned to Most Preferred and it means this action would almost certainly be most productive. The average of these scores yielding a score of the SJTEI. The possible range of scores on the SJTEI-AR is from 46 to 138 with a high score indicate a high level of emotional intelligence.

Translation of the SJTEI into Arabic

Applying a blind-back translation strategy,22 the researcher translated the SJTEI from English into Arabic. Next, one certified translator and one bilingual professor of educational psychology, working without referencing to the English version of the SJTEI, independently translated the Arabic version back to English. Finally, two certified translators independently compared the original English version of the SJTEI to the new English version that was translated back from Arabic, and rated the match between the two versions on a scale of 0 or 1. A score of zero described no match, whereas a score of 1 described perfect match. The average percentage of match was 96% which could be considered highly acceptable.22 Furthermore; the interpreter agreement was calculated using SPSS 23.0 program Crosstabs function. This produces a Kappa statistic for the level of agreement.23 Cohen23 argued that Kappa values can range between -1 and +1. Kappa>0 refers to greater than chance agreement, Kappa<0 refers to less than chance agreement, and Kappa=0 refers to chance agreement among interraters. Kappa<0.41 refers to a weak, 0.41<Kappa<0.60 refers to a moderate, and Kappa>0.60 refers to high level of agreement among interraters.24 The interrater agreement Kappa value for the SJTEI was 0.74 which indicated a high level of interrater agreement. The Arabic version of the SJTEI (SJTEI-AR) is used in all further analyses of the present study and it is available for free form the author upon request.

Neuroticism, extraversion, openness personality inventory-revised (NEO- PI-R)

Costa & McCrae25 developed the NEO-PI-R as a revised version of their original NRO-PI26 to measure the Big Five personality traits (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism). The NRO-PI consisted of 60items with 12items assigned for each of the five factors. Openness to experience measures individuals’ receptivity to different sources of experiences Conscientiousness measures individuals’ commitment to the purpose and goal-driven behavior. Extraversion measures sociability and energeticness. Agreeableness measures an individual’s interpersonal style and receptivity of the relationship with others. Neuroticism measures the intensity and frequency of negative emotions. Participants responded to each item of the NEO-PI-R on a 7-point Likert-type scale that ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree) to indicate the extent to which each item is a characteristic of them. A high score indicates a high level of the personality trait. Abd-El-Hakeem27 adapted the NEO-PI-R to the Egyptian context using a sample of 265 undergraduates in a public university in Delta Nile in Egypt. A confirmatory factor analysis showed that the NEO-PI-R Arabic Version (NEO-PI-R-AR) consisted of 55items: openness to experience (11items), conscientiousness (12items), extraversion (11items), agreeableness (11items), and neuroticism (10items). In the present study, the internal consistency reliability of the NEO-PI-R-AR using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .82 for openness to experience, .84 for conscientiousness, .80 for extraversion, .78 for extraversion, and .80 for extraversion. A high score on any subscale of the NEO-PI-R-AR indicates a high level of the Big Five factor measured by this subscale.

Academic achievement

Students’ academic achievement scores at the end of the first semester of the 2017/2018 academic year were obtained from their faculty records. These were the courses aggregated total scores, that is, the sum of on-course assignments and midterm examination score and were expressed as percentage.

Students were recruited to participate in the present study during their normal lectures at their faculty. Different numbers of students at different academic programs participated in data collection depending on students’ lectures schedule. Students were instructed that participation was voluntary and that their responses would be kept confidential. An oral consent to participate in data collection was obtained from the students. It was not possible to get approval from the institutional review board because such board is still under construction in my university. SJTEI-AR and the NEO-PI-R-AR were administered to students by trained experimenters as one package according to standardized instructions during the third week of the first semester of the 2017/2018 academic year. Students completed the SJTEI-AR and the NEO-PI-R-AR in 60 to 90 minutes. The cover sheet of all instruments instructed students to fill in some information about their names, gender, university identification numbers, ages, and socio-economic status. The researcher used students’ names and identification numbers to match students’ responses on the administered instruments and academic achievement.

Data screening

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and item-total correlations of the SJTEI-ARitems. The analyses conducted by the DeCarlo macro showed that there were nonsignificant multivariate outlier values. The variance inflation factor (VIF) and the tolerance values were 2.20 and .92 respectively, suggesting that there was nonsignificant multicollinearity in the data.28 Normality was examined both univariately and multivariately. Absolute values of skewness and kurtosis larger than 2 and 7, respectively, might imply a lack of univariate normality.29 Table 1 shows that the values of univariate skew and kurtosis of allitems were within acceptable range, suggesting that the data have normal univariate distributions. Kline suggested that multivariate normality can be assumed if the multivariate kurtosis is less than 3. The multivariate kurtosis of 2.10, Mardia’s coefficient of 39.16, and Normalized estimate of 21.33 were within acceptable range, suggesting that the data have normal multivariate distributions.29,30 Since the data appeared to be normally distributed univariate y and multivariately, the full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to analyze the variance–covariance matrices, estimate models parameters, and obtain fit indexes in all CFA analyses. The AMOS 23.0 program31 was used to run all CFA analyses.

Subscale/Items |

M |

SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Item-total correlation |

Loading |

Critical ratio (1) |

|

Utilizing own emotion |

||||||||

Item 1 |

2.2 |

0.23 |

0.34 |

0.88 |

0.66 |

0.69 |

6.55 |

|

Item 2 |

2.61 |

0.39 |

0.51 |

0.67 |

0.63 |

0.61 |

7.12 |

|

Item 3 |

2.11 |

0.45 |

0. 75 |

1.55 |

0.58 |

0.57 |

4.55 |

|

Item 4 |

2.25 |

0.23 |

-0.26 |

-0.72 |

0.65 |

0.6 |

8.2 |

|

Item 5 |

2.36 |

0.27 |

0.44 |

0.74 |

0.7 |

0.66 |

6.5 |

|

Item 6 |

2.2 |

0.31 |

0.32 |

-0.89 |

0.52 |

0.72 |

7.44 |

|

Item 7 |

2.45 |

0.51 |

0.43 |

1.33 |

0.63 |

0.59 |

4.5 |

|

Item 8 |

2.63 |

0.24 |

0.67 |

0.57 |

0.61 |

0.63 |

9.1 |

|

Item 9 |

2.44 |

0.29 |

0.56 |

0.46 |

0.5 |

0.67 |

11.54 |

|

Item 10 |

2.51 |

0.33 |

0.41 |

-1.7 |

0.55 |

0.65 |

8.45 |

|

Item 11 |

2.77 |

0.45 |

0.84 |

0.66 |

0.52 |

0.7 |

6.77 |

|

Item 12 |

2.61 |

0.47 |

0.49 |

0.45 |

0.44 |

0.69 |

10.69 |

|

Item 14 |

2.33 |

0.41 |

0.82 |

1.29 |

0.49 |

0.72 |

12.52 |

|

Item 15 |

2.6 |

0.23 |

-0.47 |

0.47 |

0.56 |

0.64 |

6.3 |

|

Item 16 |

2.51 |

0.29 |

0.59 |

0.52 |

0.64 |

0.7 |

5.2 |

|

Sensing others’ emotion |

||||||||

Item 17 |

2.8 |

0.49 |

0.41 |

0.63 |

0.72 |

0.63 |

7.2 |

|

Item 18 |

2.64 |

0.41 |

0.36 |

0.74 |

0.6 |

0.57 |

6.45 |

|

Item 19 |

2.77 |

0.36 |

-0.83 |

-1.29 |

0.56 |

0.75 |

9.45 |

|

Item 20 |

2.54 |

0.33 |

0.61 |

0.39 |

0.44 |

0.64 |

7.88 |

|

Item 21 |

2.49 |

0.24 |

0.7 |

0.41 |

0.6 |

0.72 |

9.45 |

|

Item 22 |

2.35 |

0.42 |

-0.64 |

-1.33 |

0.52 |

0.59 |

11.22 |

|

Item 24 |

2.31 |

0.36 |

0.77 |

1.11 |

0.64 |

0.62 |

4.6 |

|

Item 25 |

2.33 |

0.33 |

0.76 |

0.65 |

0.46 |

0.56 |

5.3 |

|

Item 26 |

2.76 |

0.28 |

0.25 |

1.22 |

0.59 |

0.7 |

7.19 |

|

Item 27 |

2.54 |

0.24 |

0.48 |

0.46 |

0.46 |

0.56 |

6.41 |

|

Item 28 |

2.33 |

0.19 |

0.56 |

-1.23 |

0.58 |

0.73 |

9.4 |

|

Item 29 |

2.45 |

0.47 |

-0.73 |

0.89 |

0.41 |

0.58 |

7.33 |

|

Item 30 |

2.44 |

0.53 |

0.66 |

0.46 |

0.52 |

0.64 |

5.55 |

|

Item 31 |

2.36 |

0.43 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.48 |

0.7 |

12.22 |

|

Item 32 |

2.7 |

0.39 |

0.52 |

0.95 |

0.45 |

0.6 |

9.47 |

|

Item 33 |

2.64 |

0.37 |

-0.63 |

-1.63 |

0.52 |

0.68 |

8.24 |

|

Item 34 |

2.59 |

0.3 |

0.43 |

0.7 |

0.71 |

0.74 |

6.77 |

|

Understanding of emotional context |

||||||||

Item 35 |

2.22 |

0.42 |

0.53 |

.0.61 |

0.64 |

0.56 |

8.45 |

|

Item 36 |

2.45 |

0.55 |

0.42 |

0.45 |

0.56 |

0.61 |

6.76 |

|

Item 37 |

2.51 |

0.66 |

0.31 |

1.72 |

0.67 |

0.63 |

9.12 |

|

Item 38 |

2.7 |

0.45 |

-0.85 |

0.85 |

0.6 |

0.74 |

10.65 |

|

Item 39 |

2.64 |

0.33 |

0.48 |

-1.48 |

0.52 |

0.69 |

11.25 |

|

Item 40 |

2.34 |

0.22 |

0.66 |

0.66 |

0.49 |

0.58 |

6.66 |

|

Item 41 |

2.27 |

0.61 |

-0.76 |

-1.33 |

0.44 |

0.64 |

5.98 |

|

Item 42 |

2.33 |

0.34 |

0.82 |

0.77 |

0.63 |

0.69 |

4.67 |

|

Item 43 |

2.64 |

0.53 |

-0.66 |

-0.39 |

0.51 |

0.6 |

7.52 |

|

Item 44 |

2.55 |

0.6 |

0.76 |

1.55 |

0.43 |

0.66 |

6.58 |

|

Item 45 |

2.81 |

0.32 |

0.45 |

0.49 |

0.39 |

0.55 |

9.25 |

|

Item 46 |

2.69 |

0.37 |

-0.36 |

-1.2 |

0.55 |

0.59 |

11.36 |

|

Table 1 Descriptive statistics, item-total correlations, CFA factor loadings, and critical ratio of the 44 item three correlated factor model of the SJTEI-AR

NoteN=236, Item 13 from utilizing own emotion and Item 23 from sensing others’ emotion were deleted.1 p <.01. The means of each subscale was calculated by diving a students’ total score on this subscale by the number of items of the subscale

Question 1 Does the SJTEI-AR three correlated factor model fit the data adequately?

The fit of a three correlated factor model of the SJTEI-AR to the data of the present study was examined using CFA in order to establish the measure construct validity. CFA is used to validate and confirm the structure of a measurement tool based upon a theory or a model.30 Figure 1 shows that the hypothesized model of the SJTEI-AR included three correlated factors: utilizing own emotion (16items), sensing others’ emotion (18items), and understanding of the emotional context (12items). Theitems function as observed variables for their designated factors, which in turn function as latent variables. Several absolute and relative goodness-of-fit indexes were used to evaluate the model’s goodness-of-fit to the data. Absolute fit indices included Chi-square (χ2), Standardized Root Mean-Square Residual (SRMR), and Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Relative fit indices included Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Nonnormed Fit Index (NNFI). When modeling normally distributed data, Chi-square (χ2)/df<2.0, Standardized Root Mean-Square Residual (SRMR)<0.08, and Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)<0.06, Comparative Fit Index (CFI)>0.95 and Nonnormed Fit Index (NNFI)>0.90 suggest adequate model-data fit.32,33 The final three correlated factor model of the SJTEI-AR demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (χ2=1112.36, df=899, χ2/df=1.24, RMSEA=.04, SRMR=.03, CFI=.98, NNFI=.98) after trimming 2items from the model. One item was deleted from utilizing own emotion and one item from sensing others’ emotion subscales. Thus, the final model of the SJTEI-AR consisted of 44items: utilizing own emotion (15items), sensing others’ emotion (17items), and understanding of the emotional context (12items). The standardized regression weights of the two deleteditems on their designated factors were substantially low and ranged from .08 to .04 with critical ratio ranging from .95 to 1.11 respectively, suggesting that these standardized regression weights were not statistically significant (p>.05). The critical ratio is the test statistic used to investigate the statistical significance of the factor loadings. The critical ratio values need to be>±1.96 for factor loading to be acceptable (i.e., statistically different from zero).32 The standardized regression weights (factor loadings) of theitems on their designated factors ranged from .55 to .75. The standardized regression weights were considered statistically significant because their CR values ranged from 4.50 to 12.52. There was a significant relationship between utilizing own emotion and sensing others’ emotion (r=.39, p<.01), utilizing own emotions and understanding of the emotional context (r=.35, p<.01), and sensing others’ emotion and understanding of the emotional context (r=.33, p<.01). Table 1 shows the item loadings of the SJTEI-AR model on their designated factors and the critical ratio values associated with these loadings.

Question 2 Does the SJTEI-AR three correlated factor model fit of the data better than the one factor model and the hierarchical model?

The CFA was used to examine three alternative factorial structures of the 44-item SJTEI-AR as suggested by previous studies:

Model |

χ2 |

df |

χ2/df |

SRMR |

RMSEA |

CFI |

NNFI |

Three correlated factor model |

1112.36 |

899 |

1.24 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

Global one-factor model |

2789.45 |

902 |

3.1 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

0.9 |

0.92 |

Hierarchical model |

2866.12 |

898 |

3.19 |

0.11 |

0.1 |

0.89 |

0.91 |

Table 2 Goodness-of-fit statistics for three alternative measurement models of the 44-items SJTEI-AR

Note N=236

Question 3 is the factorial structure of the SJTEI-AR generalizable (i.e., invariant) across male and female students?

A multigroup CFA (i.e., a factorial invariance test) was conducted in order to examine the generalizability (invariance) of the SJTEI-AR three correlated factor model across male and female students. The invariance testing process involves several steps in which increasingly restrictive levels of measurement invariance are explored. The three levels of measurement invariance were tested respectively: (1) configural invariance, (2) metric invariance, and (3) scalar invariance.30,32,33

Model |

χ2 |

df |

χ2 /df |

Δχ2 (1) |

Δdf |

CFI |

ΔCFI |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

NNFI |

Configural invariance |

3775.8 |

1798 |

2.1 |

- |

- |

0.988 |

- |

0.04 |

0.05 |

0.98 |

Metric invariance |

3832.39 |

1841 |

2.08 |

56.59 |

43 |

0.981 |

0.007 |

0.04 |

0.07 |

0.96 |

Scalar invariance |

3850.11 |

1884 |

2.04 |

74.31 |

86 |

0.983 |

0.005 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.97 |

Table 3 Results of the measurement invariance test of the SJTEI-AR three correlated factor model for males and females

Note Males=122, females=114. SRMR =standardized root mean square residual; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; CFI, comparative fit index; NNFI, non normed fit index.32 (1)p>.05 for all model comparisons

Question 4 Does the SJTEI-AR show adequate test-retest, internal consistency, and composite reliability?

Test-retest reliability: The SJTEI-AR was re-administered to a subsample (n=108) after 4weeks. Table 4 shows values of the test-retest reliability coefficient (stability coefficient) which ranged between .74 and .76. These values support the stability of students’ performance scores on the SJTEI-AR subscales.

SJTEI-AR subscales |

Number of items |

Test-retest coefficient(1) |

Internal-consistency coefficient(2) |

Composite reliability |

Utilizing own emotion |

15 |

0.75 |

0.72 |

0.92 |

Sensing others’ emotion |

17 |

0.76 |

0.71 |

0.93 |

Understanding emotional context |

12 |

0.74 |

0.74 |

0.89 |

Table 4 Test-retest, Cronbach’s alpha, and composite reliability for the SJTEI-AR subscales

Note (1)n=108; (2)N=236

Internal Consistency reliability: The internal-consistency reliability of the SJTEI-AR was estimated using the full sample of the present study (N=236). Table 4 shows values of the internal consistency reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s Alpha) for the subscales of the SJTEI-AR which ranged between .71 and .74. These values support the internal consistency reliability of the SJTEI-AR subscales.

Composite reliability: One way to estimate reliability for a multidimensional measure such as the SJTEI-AR within the framework of the CFA is to use the composite reliability.35 The composite reliability is given as35,36

Whereby, λ (lambda) is the standardized factor loading for item i and ε is the respective error variance for item i. The error variance (ε) is estimated based on the value of the standardized loading (λ) as:

The item r-square value is the percent of the variance of item i, explained by the latent variable. It is estimated based on the value of the standardized loading (λ) as:

Table 4 shows the composite reliability of the three factors of the SJTEI-AR as estimated by the composite reliability calculator37 and which ranged from .89 to .93.

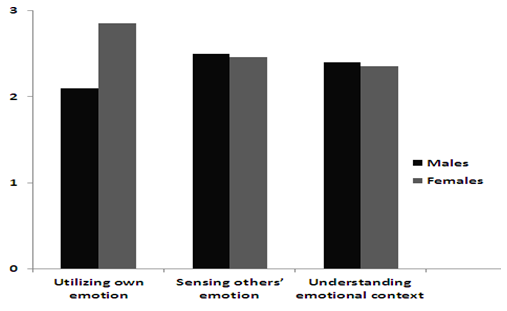

Question 5 Are there mean differences in students’ emotional intelligence as measured by the SJTEI-AR due to their gender?

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted wherein students’ gender was set as an independent variable and utilizing own emotion, sensing others’ emotion, and understanding of the emotional context were set as dependent variables. Given that the correlation coefficients among the three dependent variables were moderate and ranged from .33 to .39 (p<.01), it was appropriate to conduct MANOVA.38 The analysis showed that students’ utilizing own emotion, sensing others’ emotion , and understanding of the emotional context differed significantly by students’ gender, Pillai’s Trace=.54, F (5, 472)=11.22, p<001, η2=.19 which meant that 19% of the variance in the canonical dependent variable was explained by students’ gender . Cohen’s guidelines set .01 for small, .06 for medium, and .14 for large partial Eta Square effect size respectively.39 Thus, the η2=.19 represents a large effect size. To examine the effect of gender on each dependent variable separately, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVAs) was conducted for each dependent variable. Table 5 shows the means and the standard deviations of the three dependent variables by students’ gender.

Dependent variables |

Independent variable |

M |

SD |

F (1, 231)** |

Partial eta square η2 |

Utilizing own emotion |

20.26 |

0.21 |

|||

Males |

2.1 |

0.26 |

|||

Females |

2.85 |

0.54 |

|||

Sensing others’ emotion |

1.29 |

0.01 |

|||

Males |

2.5 |

0.47 |

|||

Females |

2.46 |

0.39 |

|||

Understanding emotional context |

1.22 |

0.02 |

|||

Males |

2.4 |

0.24 |

|||

|

Females |

2.35 |

0.19 |

|

|

Table 5 Means, standard deviations, F values, and partial eta square (η2) for the differences in utilizing own emotion, sensing others’ emotion, and understanding of the emotional context by gender

Note N=236. **p<.01. The means of each subscale was calculated by diving a students’ total score on this subscale by the number of items of the subscale

In the first ANOVA, students’ gender was set as the independent variable and utilizing own emotion was set as the dependent variable. The analysis showed significant differences in utilizing own emotion, F(1, 231)=20.26, p<.01, partial η2=.21, indicating that 21% of the variance in utilizing own emotion was accounted for by gender. Mean comparisons showed that females (M=2.85, SD=.54) showed higher levels of utilizing own emotion than males (M=2.10, SD=.26). In the second ANOVA, students’ gender was set as the independent variable and sensing others’ emotion was set as the dependent variable. The analysis showed no significant differences in sensing others’ emotion, F (1, 231)=1.29, p>.05, partial η2=.01, indicating that 1% of the variance in sensing others’ emotion was accounted for by gender. Mean comparisons showed that males (M=2.50, SD=.47) did not differ from females (M=2.46, SD=.39) in sensing others’ emotion. In the third ANOVA, students’ gender was set as the independent variable and understanding of the emotional context was set as the dependent variable. The analysis showed nonsignificant differences in understanding of the emotional context, F (1, 231)=1.22, p>.05, partial η2=.02, indicating that 2% of the variance in understanding of the emotional context was accounted for by gender. Mean comparisons showed that males (M=2.40, SD=.24) did not differ from females (M=2.35, SD=.19) in understanding of the emotional context. Figure 2 shows means of utilizing own emotion, sensing others’ emotion, and understanding of the emotional context by gender.

Figure 2 Means of utilizing own emotion, sensing others’ emotion, and understanding of the emotional context according to students’ gender.

Question 6 Does the SJTEI-AR predict academic achievement and personality dimensions?

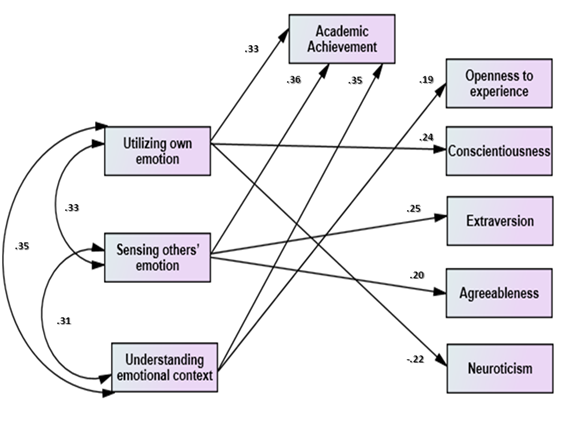

A path analysis modeling technique was used to investigate whether the SJTEI-AR can predict academic achievement and personality dimensions. In a hypothetical path analysis model, the SJTEI-AR subscales were set as independent variables (predictors). Academic achievement and Big Five personality dimensions were set as dependent variables (outcomes). Skewness and kurtosis values were between -1 and +1 supported the univariate normality of the variables in the path model. The data also showed multivariate normality because the Mardia’s Multivariate Kurtosis coefficient (Mardia's normalized coefficient=9.50) was lower than p(p+2), where p is the number of observed variables in the path model.29 Thus, the path model was examined and its parameters were estimated using the Maximum Likelihood estimation method.32,33 The AMOS 23.0 program31 was used to run the path analysis. The initial path model did not achieve adequate fit to the data fit (χ2=95.70, df=21, χ2/df=4.55, RMSEA=.10, SRMR=.10, CFI=.90, NNFI=.89). All non-significant paths in the model were trimmed one by one to improve the model fit. Figure 3 shows the final path model that achieved better fit to data than the initial model (χ2=36.45, df=25, χ2/df=1.45, RMSEA=.04, SRMR=.03, CFI=.98, NNFI=.98). The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is a criterion used to compare the fit of two nested models. A smaller AIC value indicates a better fit.30,32 The AIC for the final path model was 71.23 while the initial path model has an AIC of 82.17 suggesting the superiority of the final path model.

Figure 3 A final path model for the SJTEI-AR subscales (predictors) and academic achievement and Big Five personality dimensions (outcomes).

Does the SJTEI-AR predict academic achievement after taking into account the effect of personality dimensions and gender?

A hierarchal linear regression analysis was conducted to investigate whether the SJTEI-AR subscales could add to the variance explained in students’ academic achievement after taking into account the variance explained by students’ five personality dimensions and gender. Students’ five personality dimensions and gender were entered in block 1 as controlling variables. SJETI-AR subscales were entered in block 2 as independent variables. Academic achievement was set as a criterion variable. Table 6 shows that the R2 value for the analysis changed from .31 for block 1 to .52 for block 2. This change in the R2 value was statistically significant, F (8, 226)=18.55, p<.01. Subtracting the R2value for block 1 from the R2 for block 2, SJTEI-AR subscales were found to add 21% to the variance explained in academic achievement. Specifically, taking into account the variance explained by personality five dimensions and gender, it was found that utilizing own emotion (β=.42), sensing others’ emotion (β=.38), and understanding of the emotional context (β=.36) significantly (p<.01) predicted academic achievement respectively.

Analysis/Statistics |

Initial R2 |

R2 Final |

R2 change |

df |

F(1) |

t |

β |

Block 1 |

0.31 |

6, 229 |

11.33 |

||||

Gender |

3.95 |

-0.36 |

|||||

Openness to experiences |

4.25 |

0.32 |

|||||

Conscientiousness |

5.1 |

0.42 |

|||||

Agreeableness |

6.45 |

0.3 |

|||||

Extraversion |

4.6 |

0.3 |

|||||

Neuroticism |

4.77 |

-0.39 |

|||||

Block 2 |

0.52 |

0.21 |

8, 226 |

18.55 |

|||

Gender |

5.2 |

-0.35 |

|||||

Openness to experiences |

6.14 |

0.3 |

|||||

Conscientiousness |

7.62 |

0.39 |

|||||

Agreeableness |

5.55 |

0.28 |

|||||

Extraversion |

4.95 |

0.29 |

|||||

Neuroticism |

6.3 |

-0.37 |

|||||

Utilizing own emotion |

8.25 |

0.42 |

|||||

Sensing others’ emotion |

6.33 |

0.38 |

|||||

Understanding emotional context |

|

|

|

7.2 |

0.35 |

||

Table 6 A hierarchical regression analysis of the impact of SJTEI-AR subscales as predictors, gender and personality dimensions as controlling variables on academic achievement as an outcome

Note N=236. In block 1, the initial R2 refers to the impact of Big Five personality dimensions and gender on academic achievement. In block 2, the final R2 refers to the impact of Big Five personality dimensions, gender, and SJTEI-AR subscales on academic achievement. In block 2, the R2 change refers to the impact SJTEI-AR subscales only on academic achievement. (1) p<0.01

The present study utilized a nomological network analysis approach to empirically validate the SJTEI-AR using a sample of undergraduates in Egypt. The nomological network analysis functions at two levels; the within-network level and the between-network level.20 At the within-network level, several statistical analyses were conducted to determine the internal structure of the SJTEI-AR. A CFA showed that a three correlated factor model fit the data adequately. These three factors were labeled utilizing own emotions, sensing others’ emotions, and understanding of the emotional context. The utilizing own emotion factor described an individual’s ability to have persistence and persuasion skills to respond suitably and communicate with other people. The sensing others’ emotions described an individual's ability to recognize the emotions of others and adapt accordingly. These two factors are highly similar to the ‘managing emotions’ and ‘perceptions of emotions’ dimensions of the ability model. The understanding of the emotional context described an individual's ability to understand the context and situation in which people express and display their emotions. This finding is consistent with the findings reported by Sharma et al.’s in their original study about the factorial structure of the SJTEI using several samples from India12 and it also replicates the findings from research conducted in other countries such as England13 and Switzerland.16 Overall this finding indicates that the SJTEI-AR maintains the conceptual and theoretical content of Sharma et al.’s conceptualization of emotional intelligence within the framework of the ability model. It is important to note that the understanding of the emotional context is an exclusive and a unique dimension of emotional intelligence as described by the SJTEI-AR. This is true because previous research on emotional intelligence has failed to clearly discuss the importance of understanding the emotional context in which individuals express their emotions in order to have high emotional intelligence. This is surprising given that previous research has indicated that emotions are guided by the context in which they are expressed.40 For example, Stemmler et al.41 examined emotions of fear and anger and argued that both emotions can be displayed with remarkable differences when the context changed from a real-life situation to an imaginative one. Buss and Davidson42 argued that when children express emotions of fear that are contextually sensitive, they may not be at risk of developing behavioral problems and psychopathology. More recently, several researchers proposed that emotions context sensitivity represents a broad ability and it describes cognitive processes associated with emotional intelligence. Thus, understanding the emotional context in which emotions are displayed is a central component of measuring the emotional intelligence construct.43 In line with this notion; Sharma & Gangopadhyay12 have argued that individuals who have high levels of emotional intelligence are more likely to express emotional responses that are context-sensitive and appropriate. It is important for individuals to understand the context in which emotions are displayed in order to be able to use their own emotion and understand their own emotions as well as others’ emotions. Failing to understand emotional context and consequently display emotional responses that are context insensitive or inappropriate can damage an individual’s interpersonal relationship and threatened his or her belongingness to the social group. The CFA also demonstrated that the hierarchical model failed to achieve adequate fit to the data although Aellwing14 and Wallbott15 using samples from German and Italy respectively, argued that the hierarchical model of the SJTEI fit the data better than the three correlated factor model and the one factor model. These findings support the multidimensionality of the SJTEI-AR and indicate that the three correlated factor model is an acceptable measurement model for the SJTEI-AR as evidenced by appropriate goodness-of-fit statistics. In Fact, the nature of SJT conceptually supports the multidimensionality of the SJTEI-AR as a SJT-based measure of emotional intelligence because a SJT involves a hypothetical real-life situation with many details that indicate more than a single thing. In addition, the various response options for a SJT item typically express different constructs and the same response option can measure different constructs for different test-taker.7

The reliability analysis showed that the Cronbach’s alpha for the three factors of the SJTEI-AR were relatively low. This finding is consistent with the research findings that Cronbach’s alpha represents a low-bound estimate of reliability. Cronbach’s alpha is not appropriate of assessing reliability of a multidimensional scales because these measures are heterogeneous in nature (i.e., multidimensional) and Cronbach's alpha is based upon the assumption of parallelity which describes that all factor loadings and error variances are constrained to be equal in a given measure. Thus, Cronbach’s alpha requires the measured construct to be homogenous (i.e., unidimensional). In contrast, the composite reliability values of the SJTEI-AR were high because this type of reliability does not assume unidimensionality and it takes into account the differences in factor loadings of theitems. Hence, composite reliability is a more appropriate method for estimating the reliability of a multidimensional measure. Another advantage of the composite reliability is that it is based upon the standardized regression weights of CFA and measurement correlation errors for each item.35,36 The multigrain CFA revealed that the SJTEI-AR three correlated factor model was fully generalizable (i.e., invariant) across gender. Consistent with this finding, Shinder13 reported that the SJTEI was entirely invariant across gender and King16 found that the SJTEI was partially invariant across gender. The configural invariance indicates that males and females have the same basic conceptualization of emotional intelligence as measured by the SJTEI-AR. The attainment of configural invariance implies that males and females viewed the sameitems of the SJTEI-AR as relevant to the measurement of emotional intelligence. The attainment of metric invariance suggests that males and females might be using similar conceptual frames of reference when responding to allitems of the SJTEI-AR. That is,items have equal relevance for males and females.30 The attainment of scalar invariance highlights that males and females use the response scale in a similar way.33 Overall, these findings increase our confidence in the external validity of ASJEI-AR and provide additional evidence for the ASJEI-AR construct validity for the purpose of investigating emotional intelligence among Egyptian undergraduates and for making cross-gender comparisons. As suggested in previous literature, if measurement invariance has not been supported, valid cross-gender comparisons cannot be made.32,33

The analysis of gender differences in emotional intelligence as measured by the SJTEI-AR showed that female’s outperformed males in utilizing own emotions. This finding replicates the findings of other studies that have used the SJTEI to examine gender differences in emotional intelligence including, Sharma & Gangopadhyay12 and Wallbott.15 However, this finding is in contrast with the findings reported by Aellwing14 and King.16 Furthermore, Arteche & Chamorro‐Premuzic44 reported that females outscored males in terms of interpersonal facet of emotional intelligence. Females were also found to have higher levels of emotional skills, emotional-related perceptions, and empathy45 as well as perception of emotions including decoding facial expressions than males.45 Naghavi & Redzuan46 explained that females are more likely to be expressive of their emotions. However, males may be taught to be more conservative when expressing their emotions to emphasize their gender role stereotype. Thus, males are likely to be afraid and they may not aware of how to express and name their own emotions as well as others’ emotions. Jakupcak & Salters47 discussed that males may be more afraid of emotions and are not likely to expresses their inner feelings compared to females.

Naghavi & Redzuan46 further argued that parents talk to their daughters about feelings and emotions and provide them with necessary information and knowledge that help them display and express their emotions. Thus, females are more likely to label their emotions and feelings meaningfully and rapidly than males. Similarly, Bechtoldt48 proposed that mothers talk to their daughters in an emotional language, express their emotions with their daughters openly, read emotional stories to their daughters, and interact and support their daughters emotionally. Naghavi and Redzuan added that mothers’ emotional behavior develops and encourages daughters to become more emotional and to express their emotions more truthfully. Thus, females are more likely to perceive emotions and display high levels of social skills and emotional intelligence. However, females tended to be hesitant about feelings and taking of emotional decisions, and they place less emphasis on their intellect regarding emotional matters. Researchers have also showed that males and females differ in the type of emotions they are likely to express. While males tend to display highly-intensive healthy emotions such as excitement because this type of emotions can model their masculinity, females on the other hand are more inclined to express low or moderately-intensive emotions such as happiness because this type of emotions matches their feminine nature.49,50 The results from the path analysis modeling showed that the SJTEI-AR subscales significantly predicted the Big Five personality dimensions although the predictability of the SJTEI-AR subscales was weak (β ranged between .19 and .25). This finding supports the discriminant validity of the SJTEI-AR. This finding is partially consistent with the findings reported by Sharma et al.12 but it is in contrast with findings reported by Shinder13 and Wallbott.15 Specifically, understanding of the emotional context positively predicted openness to experience suggesting that students high in ability to understand the situation and context where people can express and display their emotions are likely to be curious, opened to experience, and interested in understanding and learning new experiences, and novelty seekers. Those students seek to discover the social environment around them to find out when and how they can express their emotions in a way that can help them gain social acceptance and maintain their belongingness to the group.51 Sensing others’ emotions positively predicted extraversion and agreeableness indicating that students with the ability to identify and recognize the emotions of others, detect emotional signals, decode emotional expression, and differentiate between real and phony emotions are more likely to be sociable, friendly, and outgoing. For students to develop their ability to sense others’ emotions, they need to interact positively with others, establish successful social networks, maintain their social ties, establish new friendships, and be respectful, kind, considerate, and helpful of others.52

Utilizing own emotions positively predicted conscientiousness because emotions usage entails the ability to use emotions to facilitate cognitive activities, pay attention to significant events, generate emotions to facilitate decision making, use emotions to consider different viewpoints, and utilize emotions as a means to develop new approaches to solve problems. These characteristics are likely to develop a conscientious person who is best described as focused, goal-oriented, and self-disciplined.53 In contrast, utilizing own emotions negatively predicted neuroticism because students lack of ability to manage and regulate emotions within self and others are likely to have high levels of neurotic behavior including moodiness, stressfulness, and irritability.54 Furthermore, the results from the path analysis modeling further demonstrated that the SJTEI-AR subscales significantly predicted academic achievement. This finding supports the predictive validity of the SJTEI-AR and is consistent with the findings of several previous studies about the psychometric properties of the SJTEI .12,13,15,16 This finding is also consistent with the research findings that have linked emotional intelligence skills to individuals’ academic achievement, professional success, and cognitive-based performance beyond the contribution of general intelligence. In addition, this finding firmly embeds emotional intelligence within the framework of the ability model that places emotional intelligence within the domain of intelligence where emotions and thought can interact together adaptively. For example, the emotions use ability within the ability model emphasizes the use of emotions to facilitate various cognitive activities and utilize emotions as a means to develop new approaches to solve problems.3

There are several pathways that linked emotional intelligence skills to academic achievement at the university level. Students with high emotional intelligence skills tend to display more positive functioning when engaged in interpersonal relationships with others and are considered by others to be prosocial and less conflictual. These favorable social skills and quality interrelationships can boost cognitive and intellectual development leading to better academic achievement and professional success. In other words, high emotional intelligence skills can facilitate prioritization of thinking, behavior management and life style adaptability which improve academic performance. Students high in emotional intelligence, particularly emotional management, are able to maintain positive social relationships with other students and significant others. These positive relationships are necessary not only for students’ collaboration to perform academic team work tasks and thus improve academic achievement but also for securing social support and boost well-being in the learning academic environment. Furthermore, Low & Nelson55 argued that emotional intelligence is a crucial factor to students’ success. Students with high emotional intelligence skills are better capable of coping with academic life demands and stressors. When students feel that they can lead their academic life successfully, they are more likely to focus on their learning and achieve academically. Jaeger & Eagan56 explained that interpersonal emotional intelligence skills, management of stressful academic events, and adaptability are important predictors of academic achievement. They argued that students’ ability to manage academic stress help them to “manage the anxiety of tests, deadlines, competing priorities, and personal crises” (p. 527) and consequently improve their academic achievement. Jaeger & Eagen56 proposed that students who are calm, flexible, and realistic when handling stressing academic events are more likely to succeed academically. They linked poor academic achievement to lack of emotional intelligence skills and argued that students with low emotional intelligence skills suffer some adjustment challenges and are likely to fail academically.

The hierarchical regression analysis further supported the predictability and incremental validity of the SJTEI-AR by demonstrating that it could significantly predict academic achievement after taking into account the effect of gender and personality dimensions. In a more conceptual and direct way, the analysis showed that the SJTEI-AR subscales could add significantly to the variance explained in academic achievement after taking into account the variance explained by gender and personality dimensions. This finding means that the emotional intelligence as measured by the SJTEI-AR could contribute to the improvement of the prediction of academic achievement beyond what can be predicted by gender and personality dimensions. Specifically, the analysis showed that utilizing own emotion was the strongest predictor of academic achievement, followed by sensing others’ emotion, and understanding of the emotional context respectively. This finding is consistent with the findings of other studies that have investigated the contribution of emotional intelligence to academic achievement after taking into account other psychological traits such as gender and self-esteem14 and academic engagement.16 In summary, the development of the SJTEI-AR is one of the assets of the present study. The findings indicated that the SJTEI-AR as a measure of emotional intelligence within the framework of the ability model demonstrated satisfactory within-network and between-network validity. Although future studies are needed to replicate these findings in additional settings, these findings suggest that researchers and practitioners can be more confident in their interpretation of SJTEI-AR scores when used with educational and clinical settings.

Educational and clinical implications for emotional intelligence

The findings of the present study highlighted several important educational and clinical Implications for the assessment and application of emotional intelligence:

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Abd-El-Fattah. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.