Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6445

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 1

Department of Psychology Technical University of Darmstadt Germany

Correspondence: Bettina Schumacher Department for Psychology Technical University of Darmstadt Alexanderstra e 10 64282 Darmstadt Germany

Received: January 29, 2019 | Published: February 11, 2019

Citation: Schumacher B, Schmitz B. Art-of-living: Validation of a novel concept to enhance one’s well-being. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry. 2019;10(1):45-52. DOI: 10.15406/jpcpy.2019.10.00625

Background: Positive Psychology (PP) explores the question of how to lead a fulfilled life with the overarching goal of increasing the general population’s well-being. Established PP approaches focus on individual characteristics such as personality attitudes and traits. A relatively new focus of well-being research that was inspired by ancient Greek philosophy, art-of-living, additionally focuses on the behavior of individuals with high well-being. Art-of-living is a holistic model of self-care strategies that address several areas (body, mind, and soul) and can be integrated into everyday life. The current paper will test the convergent and incremental validity of the art-of-living construct and investigate its potential use for PP research. To do so, we assessed the relationship of art-of-living with both well-being and two well-established concepts shown to promote well-being: happiness orientation as well as character strengths and virtues. In addition, we examined whether the art-of-living concept has added value in terms of predicting well-being as well as how it relates to other interrelated constructs. In doing so, we assume that art-of-living behaviors function as a mediator between global attitudes, character strengths, and well-being. We conducted an online survey with 636 participants from German speaking countries. Our results suggest that art-of-living is a valuable concept worthy of further attention in PP research.

Keywords: art-of-living, well-being, life satisfaction, subjective happiness, character strengths and virtues, orientation to happiness, validation

Positive Psychology (PP) seeks to improve the well-being of society as a whole.1,2 Accordingly, the primary concern of PP is the investigation of the specific conditions of well-being. According to Veenhoven,3 one must distinguish between well-being, on the one hand, and means with which to achieve it, on the other. He views well-being as a goal that can be approached in various ways. To some extent, well-being is the result of special efforts. Lyubomirsky4 for instance suggests that the variance of well-being is not only explained by genetic dispositions and external circumstances, but a huge part might be determined by individual behavior. This would imply that people are indeed able to actively influence their own well-being to a great extent. Viewing well-being as an outcome of behavior also makes sense from an educational perspective, because teaching and learning how to become happy is presumably easier than how to be happy.5 However, additional PP research is needed examining how individuals effectively increase their own well-being. Striving for well-being is an important issue for humankind that can be observed in all cultures.4 Consequently, the question of “the good life” has prevailed across both cultures and time periods and even traces back to ancient Greece.6 Pioneers such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus, and Seneca examined the question of the good life extensively, which resulted in numerous elaborations on how to lead a fulfilling life.7 Even then, people realized that there is not a single path to well-being – an idea that resulted in the distinction between hedonίa and eudaimonίa, which still serve as fundamental approaches to well-being in studies today.8,9 Hedonίa means enhancing happiness by maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. Eudaimonίa, in contrast, describes reaching fulfillment by personal growth and development. Peterson et al.10 investigated hedonίa and eudaimonίa empirically and added a third concept based on Csikszentmihalyi’s11 concept of flow. Flow describes a state of attention that results when individuals fully immerse themselves in an activity. Peterson and colleagues integrated the three orientations into a self-report questionnaire that determines one’s individual orientation to happiness (OTH). Findings show positive relations between the three orientations and life satisfaction. Greatest life satisfaction was found in people with strong scores on all three orientations. Furthermore, all three orientations were shown to be adequate predictors for life satisfaction10 – a finding that was also replicated in German-speaking countries.12 Another concept of leading a good life introduced by Peterson and Seligman13 is character strengths and virtues. Character strengths are defined as individual traits that are typically perceived to be desirable. The assumption is that using character strengths represents a virtuous life which leads to well-being. This concept, too, was inspired by ancient Greek philosophy including the works of Plato (born in 427 B.C.) and Aristotle (born in 384 B.C.). Peterson and Seligman13 compared the ancient works to the results of their own international interview studies and extracted six virtues: wisdom and knowledge, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. The researchers derived observable character strengths that, as a whole, represent the superordinate virtues and categorized them in the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA). Table 1 shows the six virtues together with the corresponding strengths. Park et al.14 found significant correlations to life satisfaction, which again were replicated in a German sample.15

|

Virtue |

Character Strengths |

|

Wisdom and knowledge |

Creativity, curiosity, judgement, love of learning, perspective |

|

Courage |

Bravery, perseverance, honesty, zest |

|

Humanity |

Love, kindness, social intelligence |

|

Justice |

Teamwork, fairness, leadership |

|

Temperance |

Forgiveness, humility, prudence, self-regulation |

|

Transcendence |

Appreciation of beauty and excellence, gratitude, hope, humor, spirituality |

Table 1 Virtues and corresponding character strengths13

Schmitz16 considered another approach to well-being that also has its roots in the ancient Greek philosophy – art-of-living. Art-of-living was conceptualized by Socrates, Aristotle, and Plato and also addresses the question of the good life. Today, art-of-living is still a subject of philosophical discourse.15 However, despite the broad philosophical base, art-of-living has received little attention in psychological research.17 Thus, Schmitz16 first examined the concept from a psychological point of view and then developed a measurement instrument. Because the concept focusses on strategies that enhance well-being in everyday life, art-of-living is relevant to PP. Key to art-of-living is a healthy relationship to oneself, which requires a deliberate, self-determined, and amicable way of living. According to Schmid16 “art-of-living is not meant as the easy, happy-go-lucky life but the conscious, reflected conduct of life. Therefore, it can cost great efforts as well as be a special source of fulfillment”. Art-of-living provides strategies to implement this way of living. It is assumed that a successful self-relation results from self-care. Self-care means being supportive to oneself, treating oneself well, and building a friendship with oneself. The areas in which self-care can be implemented are roughly divided into body, mind, and soul. The resulting self-relationship is viewed as the foundation on which one’s relationship to others and the environment is based. It is important to note that art-of-living is not narcissism or egoism but rather a healthy level of self-care. A functional self-relationship, resulting from art-of-living, is viewed as a prerequisite for building supportive social relationships and vice versa. Below, we will explain the self-care areas in more detail using psychological terms rather than the philosophical terms body, mind, and soul. Physical self-care aims at somatic well-being, which can be increased, for example, by healthy nutrition and physical activity. Emotional self-care is related to affective aspects and involves emotion management. For example, it can be achieved by successfully coping with stressful experiences. Mental self-care is related to cognition and describes the pursuit of knowledge, experiences, and broadening one’s horizon, which can be achieved by being open to new insights and experiences.

Because the concept integrates the different areas of existence, we view art-of-living as a holistic model. Sin and Lyubomirsky18 suggest that practicing multiple and different PP exercises combined might be more effective than only single isolated exercises. We assume that art-of-living meets this criterion. It should be noted that there are wide overlaps between physical, emotional, and mental self-care, so that the areas are inextricably interwoven. For example, we would agree that somatic well-being includes not only physical but also emotional parts. A strict separation is not necessary to benefit from art-of-living. On the contrary, the interconnections between the areas might be an advantage in training contexts because, due to the art-of-living’s holism, if one area is influenced positively, it might subsequently positively affect the others. To operationalize the art-of-living concept, Schmitz19 compared the philosophical conceptions of art-of-living with the results of qualitative interviews, which were based on open questions, e.g. What does art-of-living mean to you? Schmitz then designed a categorical system based on the interviews to identify several core components of art-of-living and, subsequently, generate items. Most common associations with art-of-living related to optimism, a self-determined way of living, and openness. Further associations were conscious exploration of pleasant activities, good relationships, pragmatism, balance and reflection. Apart from the general understanding of art-of-living, Schmitz19 was particularly interested in the question of whether art-of-living is assumed to be learnable. To address this question, he added the item Art-of-living is something you are either born with or not.

Overall, results indicated that the philosopher’s conceptualization is close to what the general population associates with art-of-living. The majority of participants viewed art-of-living to be learnable and associated with something positive – i.e., they saw the concept as a conscious and desirable way of life including an accepting and serene attitude. The findings were integrated into the self-report art-of-living-questionnaire (ALQ). Initial studies indicate that the ALQ is a promising measure of art-of-living. Art-of-living as measured with the ALQ appears to be normally distributed and largely independent of demographic variables such as age, sex, and education level.19 Regarding initial analyses of convergent validity, Traulsen et al.20 confirmed expected correlations (r) with related concepts such as resilience (.68***), sense of coherence (.69***), and wisdom (.58***). Regarding the relationship to life-satisfaction, the ALQ predict life satisfaction quite well: As shown by Schmitz [19], nearly two-thirds of the variance in satisfaction with life is explained by the art-of-living variables (R²=.61, F(11,1093)=170.4, p<.001). In follow-up studies, the questionnaire was further improved and supplemented with three additional components that appear to be crucially related to the art-of-living concept: Self-actualization (inspired by Carl Rogers,21 reflection, and meaning. Analyses suggested that the revised version is superior and measures art-of-living more accurately.19 In numerous training studies with different target groups, art-of-living indeed was revealed to be learnable.22−25 All components are described in Table 2.

|

Self-determined way of living |

setting one’s own goals and making decisions by oneself |

|

Self-efficacy |

being able to deal with difficult situations and problems |

|

Self-knowledge |

knowing one’s own strengths and weaknesses |

|

Self-actualization |

striving for growth and personal development |

|

Meaning |

giving meaning to life |

|

Physical care |

caring for one’s body, e.g. by physical activity |

|

Savoring |

doing something one likes and enjoying it |

|

Balance |

finding balance between different emotions and cognitions |

|

Integrating different areas of living |

living a flexible work-life balance |

|

Coping |

being able to cope with unpleasant events |

|

Positive attitude towards life |

having a positive look on life |

|

Serenity |

keeping calm even in difficult situations |

|

Openness |

being open to new developments in one’s life and the world |

|

Optimization |

trying to get good results and trying to become better |

|

Shaping of living conditions |

shaping one’s environment to meet one’s own needs, e.g. home |

|

Reflection |

thinking about oneself and life |

|

Social contact |

caring about others, building supportive relationships |

Table 2 Descriptions of art-of-living components

The current study examines the art-of-living concept’s value for PP research. To do so, we will explore the art-of-living’s potential for well-being studies under consideration of other PP constructs – i.e., orientation to happiness as well as character strengths and virtues. The three concepts can be described as resource orientated, everyday relevant, and focused on human well-being. They also overlap conceptually. For example, openness, optimism, and social contacts are discussed in both the VIA concept and art-of-living. Regarding OTH, the orientations hedonίa and eudaimonίa are reflected in diverse art-of-living components. For example, the art-of-living component savoring is related to the hedonistic approach. Despite common roots and overlaps in terms of content, the three concepts are also fundamental distinct. We consider orientation to happiness as global attitudes of life, similar to universal life mottos, whereas the art-of-living concept contains attitudes, too, but additionally describes what people actually do to realize a certain orientation. We explicitly refer to the need for a model describing actual behavior, as art-of-living does. With respect to character strengths and virtues, we also see contrasts to art-of-living. That is, the former is rather a character model in which existing potentials must be discovered and developed, whereas the latter includes selectable and learnable strategies that depend less so on predetermined resources and more so on practice. As a consequence, it is difficult to learn character strengths, whereas art-of-living strategies are easier to learn because they are less dependent on previous potential. Another difference is that the VIA concept is more related to social norms and thus rather includes moralizing aspects. However, the art-of-living’s nature is more self-focused and less strong related to social conventions, in that art-of-living is less normative. Because we assume that well-being is the outcome of a conscious way of living represented by art-of-living, we included satisfaction with life and subjective happiness as criteria, since both are regarded as components of well-being. Eger and Maridal26 view well-being as a continuum with a cognitive and an affective pole. The evaluation of satisfaction with life is located more towards the cognitive pole, whereas the evaluation of subjective happiness is located more towards the emotional pole. In summary, art-of-living is a new, holistic approach in PP research. The concept focuses on self-care, which can be implemented through a self-determined, conscious, and amicable way of living. Self-care can be realized in several areas (body, mind, and soul) and leads to self-friendship, which in turn supports intact relationships to environment and vice versa. The art-of-living model provides several learnable and selectable behavior strategies that are available for a broad group of people. Implementing art-of-living in everyday life is assumed to enhance well-being.

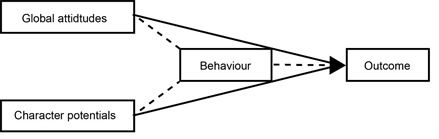

First, the present study aims to assess the convergent validity of art-of-living. Due to the strong relatedness between attitudes and behavior (represented by art-of-living) and outcome (represented by well-being), we assume significant positive relationships between art-of-living and satisfaction with life (hypothesis 1.1) as well as subjective happiness (hypothesis 1.2). We expect the effect magnitude to be moderate yet not high, thus reflecting the idea that behaviors and outcomes are not the same. We then investigate the relationships between art-of-living and both OTH (hypothesis 2.1) and VIA (hypothesis 2.2), again expecting positive relationships. Due to the fact that the concepts are viewed as alternative yet distinct means to well-being, those correlations should not to be too high. Second, we investigate the incremental validity of art-of-living. To do so, we first predict well-being on the basis of OTH and VIA and then include art-of-living. If art-of-living contributes to the prediction of satisfaction with life above and beyond OTH (hypothesis 3.1) and VIA (hypothesis 3.2) as well as the prediction of subjective happiness above and beyond OTH (hypothesis 3.3) and VIA (hypothesis 3.4), incremental validity can be viewed as given. Third, on a meta-level, we investigate the relationships among all variables – i.e., OTH, VIA SWLS, SHS, and art-of-living. With it, we aim to anchor art-of-living within the nomological network, which means trying to reveal the art-of-living’s position within the concealed structure among interrelated constructs. Due to its focus on everyday behavior, we consider the possibility that art-of-living takes on a mediating role in the prediction of satisfaction with life by OTH (hypothesis 4.1) and VIA (hypothesis 4.2) as well as in the predicting subjective happiness by OTH (hypothesis 4.3) and VIA (hypothesis 4.4). OTH represents global life attitudes, whereas the VIA concept represents rather character traits. Art-of-living, in contrast, represents selective behaviors that are less dependent on dispositional resources and are, instead, learnable. In addition, the concept is assumed to be connected to the relationship of both one’s global orientation to happiness and character strengths with well-being. That would implicate that global attitudes (OTH) and character traits (VIA) unfold their advantages in their entirety only in combination with appropriate behaviors, represented by art-of-living. If so, the correlations between OTH and VIA to the two well-being criteria disappear when the art-of-living’s influence is eliminated. The underlying, hypothetical, nomological network is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Hypothetical nomological network: Behaviors (represented by art-of-living) are assumed to mediate the relationships of both global attitudes and character traits to the outcome (well-being). If so, the direct effects (solid lines) disappear when controlling for the art-of-living’s influence.

Sample

A total of 2,005 individuals followed the link leading to the survey. The completion rate was 636 (31.72 %). No participant was excluded from the sample. 111 participants were males (17.45 %); six participants did not specify their gender (0.95 %). The mean age was 27.61 years (SD= 10.64). The youngest participant was 15 years old, the oldest 73.

Design

This cross-sectional study was implemented as an anonymous online-survey. The link to the survey was spread via social networks and email in German speaking countries. The measurements used were presented in the order of the description below. The questionnaire items were presented in randomized order. The study duration was approximately 40 minutes.

Measurement instruments

The instruments used for measuring art-of-living, character strengths and virtues, orientation to happiness, satisfaction with life, and subjective happiness are described in the following.

Art-of-living questionnaire

The art-of-living questionnaire consists of 131 items assigned to 17 scales. Participants indicated their agreement with the items on a six-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). For internal consistency (Cronbach’s α), Schmitz19 reported .95. We replicated this value in the current study (.97). Table 3 displays the internal consistencies for the sub scales. Example items are presented as well.

|

Scale (item count) |

α1 |

α2 |

Example item |

|

Balance (6) |

0.61 |

0.69 |

I can plan well but can also intuitively approach a task. |

|

Coping (7) |

0.52 |

0.69 |

Faced with stress and pressure, I specifically eliminate the causes. |

|

Serenity (6) |

0.77 |

0.83 |

I do not easily get worked up. |

|

Savoring (8) |

0.64 |

0.8 |

I spoil myself. |

|

Physical care (6) |

0.82 |

0.85 |

I pay attention to my body. |

|

Integrating different areas of living |

0.63 |

0.6 |

I take enough time for my hobbies. |

|

Openness (7) |

0.7 |

0.77 |

I like to take on new challenges. |

|

Optimization (8) |

0.69 |

0.75 |

I utilize my strengths quite well. |

|

Positive attitude towards life (10) |

0.78 |

0.87 |

Altogether, I expect that I will experience more good things than bad things. |

|

Self-determined way of living (7) |

0.77 |

0.73 |

I take control of my own life. |

|

Social contact (9) |

0.65 |

0.85 |

I care about my friendships. |

|

Self-efficacy (8) |

0.88 |

0.86 |

For every problem, I can find a solution. |

|

Self-knowledge (10) |

0.72 |

0.86 |

I know my own strengths and weaknesses. |

|

Shaping of living conditions (6) |

0.53 |

0.82 |

I design my home to my taste. |

|

Self-actualizationa (8) |

- |

0.83 |

I realize my possibilities. |

|

Reflectiona (9) |

- |

0.81 |

I analyze my behavior and learn from it. |

|

Meaninga (11) |

- |

0.83 |

My life has meaning. |

Character strengths and virtues

Character strengths and virtues were measured using a German adaption of the short form of the VIA provided by Furnham and Lester.27 It contains one item per character strength. The 24 items are assigned to six superordinate virtues. Table 4 provides one example item per scale. Participants assess the extent of their own character strengths in comparison to the general public using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from well below average to well above average. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in the current study is .80 for the overall scale, .67 for wisdom, .42 for courage, .40 for love, .38 for justice, .46 for temperance, and .60 for transcendence (Furnham & Lester27 reported .66, .55, .52, .48, .55, and .76 for the sub scales, respectively). Due to partially insufficient reliability of the subscales, we used the VIA overall score in our analyses; we used the subscales only for specific analyses.

|

Scale |

Example Item |

|

Wisdom |

Curiosity: interest in, intrigued by many things |

|

Courage |

Bravery: courage, valor, fearlessness |

|

Love |

Kindness: generosity, empathy, helpfulness |

|

Justice |

Citizenship: team worker, loyalty, duty to others |

|

Temperance |

Self-control: ability to regulate emotions, lack of impulsivity, transcendence |

|

Transcendence |

Appreciation of beauty: excellence seeking, experience of awe/wonder |

Table 4 Internal consistencies and example items of the VIA short form27

Orientation to happiness

The Orientation to Happiness Questionnaire developed by Peterson, et al.10 measures each of the three orientations (life of pleasure, life of engagement, life of meaning) with six items. Ruch et al.15 translated the questionnaire to German. Participants indicated their agreement with the items on a 5-point Likert scale (from very much unlike me to very much like me). An example item for life of pleasure is Life is short - eat dessert first. An example for life of engagement is Regardless of what I am doing, time passes very quickly. An example item for life of meaning is I have a responsibility to make the world a better place. For Cronbach’s α, Ruch et al.14 reported .73 for life of pleasure, .63 for life of engagement, and .75 for life of meaning. In the current, we found alpha values of .70, .52, and .71, respectively, as well as .74 for the overall OTH scale.

Satisfaction with life scale

To measure global life satisfaction, we used the well-established five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) from Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin.28 The German adaption comes from Glaesmer et al.28 The one-dimensional self-report instrument measures participants’ agreement on a 7-point Likert scale. An example item is The conditions of my life are excellent. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) is reported to be .92. In the present study, we found an alpha value of .88.

Subjective happiness scale

The extent to which people judge themselves as happy was measured with the German version of the one-dimensional Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) of Swami et al.30 The original version is from Lyubomirsky and Lepper.31 Participants indicated their agreement with the four items on a 7-point Likert scale. An example item is Some people are generally very happy. They enjoy life regardless of what is going on, getting the most out of everything. To what extent does this characterization describe you? The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) is reported to be .82. This value was replicated in the present study (.81).

Scores on the art-of-living questionnaire could range from 0 to 786 points. The overall mean score was 579.30 (SD=61.77). The lowest value attained was 261, the highest 748. As expected, the graphical analysis revealed art-of-living to be normally distributed. We tested whether the demographic variables have an impact on art-of-living. We found no correlation (r) between gender and overall art-of-living (.02). We found a significant, yet weak correlation (r) between overall art-of-living and age (.15***). To test convergent validity, we first calculated the correlations controlled for age and gender between the overall scores scale. The correlation between ALQ and SWLS is .60 and SHS .61. The correlations between ALQ and VIA and ALQ and OTH both are .58. We then examined the ALQ subscales. As mentioned above, we could not replicate all Cronbach’s α values for the OTH and VIA subscales. Thus, scales with low reliability should be interpreted carefully. All values are displayed in Table 5. Due to space reasons, we will concentrate on the strongest correlation per column. SWLS has the strongest correlation with the ALQ subscale meaning and the SHS subscale positive attitude towards life (both .70). VIA’s wisdom correlates highest with the ALQ subscale openness (.51). VIA’s transcendence correlates highest with ALQ’s positive attitude towards life (.58). OTH’s pleasure correlates highest with ALQ’s savoring (.44). OTH’s meaning shows the strongest connection to ALQ’s meaning (.41). An unexpected result is the weak negative correlation of ALQ’s self-reflection scale with SWLS (-.07) and SHS (-.11). In order to determine whether the art-of-living concept explains variance in well-being beyond character strengths and virtues and orientation to happiness, we calculated two hierarchical regression analyses. We used satisfaction with life and subjective happiness as criteria. Again, the calculations were conducted using the overall scale values. In the first step, we calculated the reduced model with VIA and OTH as predictors. In the second step, we expanded this model to ALQ. Subsequently, we tested the reduced and extended model for significant differences using F-tests. The results are presented in Table 6. In both cases, the proportion of explained variance in the criteria showed a significant increase when including art-of-living (for SWLS, F(1, 632)=209.28, p<.001; for SHS, F(1, 632)=195.38, p<.001).

|

Art-of-living |

SWLS |

SHS |

Character Strengths and Virtues (VIA) |

Orientation to Happiness (OTH) |

|||||||||

|

Total |

WISD |

COURa |

LOVEa |

JUSTa |

TEMPa |

TRAN |

Total |

PLEA |

ENGAa |

MEAN |

|||

|

Total |

.60*** |

.61*** |

.58*** |

.44*** |

.38*** |

.29*** |

.34*** |

.13*** |

.53*** |

.58*** |

.42*** |

.49*** |

.36*** |

|

Balance |

.28*** |

.37*** |

.45*** |

.32*** |

.22*** |

.32*** |

.29*** |

0.04 |

.43*** |

.42*** |

.34*** |

.37*** |

.22*** |

|

Coping |

.31*** |

.37*** |

.41*** |

.30*** |

.27*** |

.15*** |

.26*** |

.19*** |

.33*** |

.41*** |

.25*** |

.44*** |

.23*** |

|

Serenity |

.32*** |

.41*** |

.26*** |

.14*** |

.17*** |

0.04 |

.09* |

.30*** |

.22*** |

.18*** |

0.01 |

.21*** |

.09* |

|

Savoring |

.43*** |

.52*** |

.31*** |

.21*** |

.08* |

.17*** |

.12** |

0 |

.43*** |

.42*** |

.45*** |

.29*** |

.18*** |

|

Physical care |

.30*** |

.26*** |

.30*** |

.23*** |

.25*** |

.11** |

.15*** |

.09* |

.25*** |

.31*** |

.21*** |

.22*** |

.24*** |

|

Integrating different areas of living |

.42*** |

.37*** |

.26*** |

.17*** |

.10** |

.11** |

.17*** |

.10** |

.27*** |

.28*** |

.26*** |

.23*** |

.12** |

|

Openness |

.25*** |

.34*** |

.45*** |

.49*** |

.29*** |

.15*** |

.24*** |

-0.04 |

.41*** |

.43*** |

.27*** |

.33*** |

.32*** |

|

Optimization |

.52*** |

.41*** |

.44*** |

.35*** |

.43*** |

.20*** |

.28*** |

.14*** |

.30*** |

.34*** |

.21*** |

.39*** |

.17*** |

|

Positive attitude towards life |

.60*** |

.70*** |

.47*** |

.25*** |

.21*** |

.28*** |

.23*** |

.09* |

.57*** |

.51*** |

.41*** |

.38*** |

.32*** |

|

Self-determined way of living |

.46*** |

.41*** |

.38*** |

.32*** |

.39*** |

.14** |

.21*** |

0.03 |

.30*** |

.37*** |

.27*** |

.35*** |

.20*** |

|

Social contact |

.41*** |

.40*** |

.37*** |

.17*** |

.19*** |

.41*** |

.28*** |

0.05 |

.35*** |

.31*** |

.27*** |

.24*** |

.17*** |

|

Self-efficacy |

.48*** |

.53*** |

.51*** |

.42*** |

.41*** |

.17*** |

.29*** |

.11** |

.43*** |

.45*** |

.31*** |

.42*** |

.26*** |

|

Self-knowledge |

.41*** |

.38*** |

.53*** |

.45*** |

.37*** |

.29*** |

.35*** |

.11** |

.40*** |

.46*** |

.32*** |

.38*** |

.29*** |

|

Shaping of living conditions |

.47*** |

.38*** |

.31*** |

.26*** |

.21*** |

.14*** |

.17*** |

0.01 |

.29*** |

.38*** |

.36*** |

.30*** |

.17*** |

|

Self-actualization |

.47*** |

.41*** |

.48*** |

.42*** |

.36*** |

.22*** |

.27*** |

.02*** |

.42*** |

.52*** |

.34*** |

.43*** |

.36*** |

|

Reflection |

-.07* |

-.11** |

.21*** |

.27*** |

0.05 |

0.05 |

.15*** |

.14*** |

.09* |

.22*** |

0.06 |

.13* |

.27*** |

|

Meaning |

.70*** |

.64*** |

.45*** |

.27*** |

.33*** |

.29*** |

.25*** |

0.05 |

.46*** |

.55*** |

.36*** |

.43*** |

.40*** |

Table 5 Partial correlations of art-of-living to VIA and OTH as well as satisfaction with life (SWLS) and subjective happiness (SHS)

N=636. ***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05. Correlations controlled for age and gender

WISD, wisdom; COUR, courage; JUST, justice; TEMP, temperance; TRAN, transcendence; PLEA, pleasure; ENGA, engagement; MEAN, meaning

aCaution: Scale shows low reliability (α≤.55)

|

|

SWLS |

SHS |

||

|

Β |

ΔR2 |

β |

ΔR2 |

|

|

Step 1 |

|

.16*** |

|

.19*** |

|

VIA |

0.07 |

|

.18*** |

|

|

OTH |

.36*** |

|

.32*** |

|

|

Step 2 |

|

.21*** |

|

.20*** |

|

VIA |

-.17*** |

|

-0.05 |

|

|

OTH |

.13** |

|

.10* |

|

|

ALQ |

.61*** |

|

.59*** |

|

|

Total R2 |

|

.37*** |

|

.39*** |

Table 6 Hierarchical regression analyses to predict well-being

N=636. *p<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001

SWLS, Satisfaction with Life Scale; SHS, Subjective Happiness Scale; VIA, Values in Action Inventory of Strengths short form; OTH, Orientation to Happiness; ALQ, Art-of-Living Questionnaire

Subsequently, to account for the complexity of the art-of-living concept, we repeated the prediction. However, in the second step, we added art-of-living not as an overall value but instead as the 17 subscales by forced entry. In doing so, the explained variance increases to 56% for SWLS and 58% for SHS. Thus, by using art-of-living subscales for prediction, in both cases we can explain an additional 19% variance compared to the overall ALQ values. Again, both F-tests revealed significant improvement in the expanded models (for SWLS, F(616, 17=33.28, p<.001; for SHS, F(616,17)=33.26, p<.001). To examine the underlying nomological structure and the connections among the constructs, we calculated a mediated path model including all five constructs. For the sake of clarity, the model is pictured separately for the two predictors below. We investigated the direct as well as the indirect effects of VIA and OTH on SWLS and SHS. Art-of-living was inserted as a mediator. As apparent from Figure 2, the correlations between OTH and the two well-being indicators SWLS and SHS are stronger when art-of-living is not included. The β-weight between OTH and SWLS decreases from .36 to .13 when controlling for art-of-living. With OTH and SHS, it behaves similarly: The regression weight decreases from .32 to .10. VIA does not appear to be related to SWLS. However, controlling for the influence of art-of-living results in a weak negative relationship of -.17. VIA and SHS show a weak positive relationship of .18, which disappears when controlling for art-of-living (Figure 3).

In summary, our analyses support hypothesis 1. We found significant relationships between art-of-living and two different well-being criteria. Art-of-living appears to be closely related to satisfaction with life (hypothesis 1.1) and subjective happiness (hypothesis 1.2). The most important ALQ subscale in regard to SWLS is meaning and in regard to SHS positive attitude towards life. All other art-of-living components with the exception of reflection are positively related to well-being. Nevertheless, art-of-living and well-being are not the same – otherwise, the correlations would have been higher. The negative correlation of ALQ’s self-reflection scale to the well-being criteria could be owed to the circumstance, that self-reflection can include both short-term and long-term effects which potentially differ from each other. Thinking about one’s own life, motives, values, needs etc. might be uncomfortable in the first moment. But this self-confrontation could initiate functional changes of own attitudes and behavior in the long term, so that positive effects might occur delayed. Similar values were found for OTH (hypothesis 2.1) and VIA (hypothesis 2.2), again indicating conceptual overlaps. On the subscale level, we found additional support for convergent validity, since conceptually similar subscales show particularly high correlations (e.g. VIA’s wisdom and ALQ’s openness, VIA’s transcendence and ALQ’s positive attitude towards life, OTH’s meaning and ALQ’s meaning, as well as OTH’s pleasure and ALQ’s savoring). Again, these moderate correlations indicate that art-of-living is distinct from other established PP concepts. We conclude that the broad nature of the art-of-living concept contains certain personality aspects, attitudes and, in particular, concrete behavioral aspects not represented by the consulted established constructs.

Hypothesis 3 refers to incremental validity by proposing that the ALQ scale explains variance in well-being above and beyond character strengths (hypothesis 3.2 and 3.4) and orientation to happiness (hypothesis 3.1 and 3.3) in context of regression analyses. This hypotheses were supported by the analyses. Thus, the notion that art-of-living includes facets relevant to well-being beyond OTH and VIA appears to be justified. The results indicate that the art-of-living variables explains variance in well-being even if it is introduced in the second step. This shows not only that art-of-living contains novel aspects but also that those supplementary aspects are indeed relevant to one’s life satisfaction and subjective happiness and, thus, should be taken into account in well-being research. Hypothesis 4 assumed a mediating role of ALQ. In a mediated path analysis, VIA and OTH were used to predict both SWLS and SHS, in which art-of-living was used as a mediator. When controlling for the art-of-living influence, the impact of OTH decreased but did not disappear completely. This indicates a partial mediation effect of art-of-living on the relationship between OTH and SWLS (hypothesis 4.1) as well as SHS (hypothesis 4.3). We found evidence of a complete mediation for the relationship between VIA and SHS (hypothesis 4.4), in that the relationship disappeared when controlling for art-of-living. Regarding VIA and SWLS (hypothesis 4.2), the non-significant regression weight became negative and significant, indicating a weak suppression effect caused by art-of-living. In summary, the results indicate that art-of-living does indeed partially explain the relationship between the predictors and the criteria, thus partially confirming the mediation hypotheses (with the exception of 4.4, which was confirmed completely and 4.2 for which we found a suppression effect). Altogether, we found support for the necessity of including art-of-living as a novel construct in well-being studies. Art-of-living has been shown to be valid with regard to convergent and incremental validity. Furthermore, we obtain first indications that art-of-living is located in the concealed nomological structure among different constructs. Art-of-living has a mediating character in terms of the relation between global attitudes, character potential, and well-being. Explaining this in more detail, it is conceivable that art-of-living provides the required strategies to live in accordance with one’s global orientation to happiness. For example, an individual with a pleasure orientation will probably benefit most if it possesses and actually uses concordant strategies such as regularly taking time for conscious enjoyment. Similarly, art-of-living might facilitate the exploitation of one’s character strengths. If the concrete behavior strategies represented by art-of-living are lacking, the advantages of global happiness orientations as well as existing character potential appear to be reduced. We interpret this as support for the importance of art-of-living in PP research. Art-of-living includes information not represented in current PP concepts. Particularly the emphasis on behavioral aspects of the good life appears promising. Accordingly, PP should focus even more strongly on what happy people actually do in their everyday lives. Furthermore, a holistic view of well-being including global attitudes, character strengths and everyday behavior seems appropriate. The art-of-living strategies are designed to be easily implemented by a broad target group while, at the same time, can be integrated into everyday life with practice. Thus, we see huge potential to enhance well-being by using the art-of-living approach.

The findings provide hints for the need of a holistic approach such as art-of-living. However, it is important to note that the result of the current study are limited. First, the sample does not represent the German population with regard to basic characteristics such as age and gender. Besides, self-selection of people interested in philosophical and psychological topics might have impacted the results, since people interested in art-of-living might have been more likely to participate in the survey. A further restriction results from the use of the VIA 24-item short version. Using one item per strengths might not adequately measure the concept. In addition, the factor structure of the measurement obtained by Furnham & Lesters27 differs slightly from the original VIA conception by Peterson & Seligman.13 Thus it might be, that in some parts different concepts are assessed and the VIA concept is not perfectly represented by the short form. However, due to the length of our survey, in practical sense the short version was more appropriate – i.e., the survey took approximately 40 minutes to complete and completion rate was only 31.72%. Hence, the extent to which the results can be replicated using a more detailed survey of VIA such as the VIA-120 or -240 is unclear and a potential topic for future research. It is also important to discuss the unexpected result shown in the mediation model in regard to VIA and SWLS. As already mentioned, the formerly non-existent relationship became significant and negative when art-of-living was controlled for, indicating art-of-living to neutralize an existing weak, negative relation. Due to the above mentioned limitations, this weak effect should not to be attributed too much importance. Nevertheless, we will provide a possible explanation below. As mentioned in the beginning, the VIA concept is naturally related to questions of moral and ethics – after all, it is characteristic of a decent and reputable character. Thus, the VIA concept might be partly in contradiction to art-of-living, because art-of-living stronger focuses on self-determination. By eliminating the art-of-living influence, and with that the emphasis on self-endorsement and self-care, the moralizing aspects represented by VIA related to social conventions, judgement, and conscience that remain may be responsible for the observed negative effect on life satisfaction.

As we have shown, introducing art-of-living in PP research might have potential advantages, because it is related to well-being and includes aspects not represented in current PP concepts. The art-of-living’s advantages are the holistic view of human beings, the freedom of strategy choice, the emphasis on actual behavior rather than solely on global attitudes or character traits, and the resulting implication of learnability. Art-of-living combines various components and provides concrete behavior strategies to implement a good life. The approach’s versatile nature makes art-of-living appealing for a broad target group. The statistical analyses provide support for the concept’s validity. We’ve got an idea of where art-of-living is located in the nomological network of interrelated constructs and the underlying mechanisms. Hence, we approached the conceptual anchoring of art-of-living in PP research. Because art-of-living appears to provide required behavior strategies that enable people to make the most of their global happiness orientation and exploit existing character potential, we advocate for well-being studies to include the art-of-living concept.

We thank Samsung Electronics of the Amazon LTDA by means of the Amazon Informatic Law; it foments research and technological development of the region in partnership with the University of the State of Amazonas, and the Research and Development Center UNA-SUS Amazonia of the said university.

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Schumacher, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.