Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6445

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 4

1Division of Clinical Cancer Epidemiology, Department of Oncology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sweden

2Department of Women's and Children's Health, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden

3Sophiahemmet University, Sweden

4Division of Clinical Cancer Epidemiology, Department of Oncology and Pathology, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden

5Children?s Cancer Hospital Egypt 57357, Egypt

6Cairo University Hospital, Department of Oncology, Egypt

7Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden

8Department of Social Work, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

Correspondence: Hanan El Malla, Division of Clinical Cancer Epidemiology, Department of Oncology, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy at University of Gothenburg, SE 413 45 Gothenburg, Sweden, Tel 46 735 004512

Received: January 31, 2017 | Published: March 15, 2017

Citation: Malla HE, Kreicbergs KNU, Steineck G, Elborai YES, Wilderäng U, et al. (2017) Advances in Pediatric Oncology- a Five-Year Nation-Wide Survival follow-up at Children’s Cancer Hospital in Egypt. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry 7(4): 00443 DOI: 10.15406/jpcpy.2017.07.00443

Background: Childhood cancers survival rates in Egypt are appreciated to less than 30 percent while the treatment options are stagnant in progress and the reasons behind are undisclosed. The Children’s Cancer Hospital Egypt has adopted the Western treatment protocols since 2007, which gives new means to improve cancer survival and care.

Methods: This study was designed to investigate possible predictors of mortality to childhood cancers. We administered two questionnaires, one at the start of chemotherapy and one at the third chemotherapy cycle, to 304 parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer. The five-year survival rate was estimated

Results: Among the 304 children diagnosed with cancer at the Children’s Cancer Hospital, 274 children were followed up five years after data collection. We found that 58 percent (n=176) had survived while 10 percent were lost to follow-up. The only statistically significant difference found between the group that survived and the group that did not survive in relation to numerous psychosocial and demographic factors was mother’s level of education with a p-value 0.02.

Conclusion: The observed survival rate of the children in our group is 58 percent, with an addition of 10 percent lost to follow-up. An increase in childhood cancer survival is clearly noted compared to official statistics for earlier years. The only predictor for survival in our study group was higher education level among mothers.

Keywords: childhood cancer, survival, mortality, pediatric oncology, Egypt, children’s cancer hospital, CCHE

“The struggle of life is one of our greatest blessings, it makes us patient, sensitive, and Godlike, it teaches us that although the world is full of suffering, it is also full of the overcoming of it” (Helen Keller). Indeed childhood cancer is a major challenge and a crisis to any family, and by knowing that there is hope, the challenge is easier to endure. Childhood cancer has a worldwide incidence of more than 175000 per year and a mortality rate of approximately 96000 per year.1 In the United States in 2012, approximately 12 060 children under the age of 15 were expected to be diagnosed and 1340 children expected to die from cancer.1 In Sweden, approximately 300 children are diagnosed with cancer annually and three out of four children are estimated to become long-term survivors.2 In Egypt, like in many Arab countries, the true cancer incidence is unknown since there is no national registry. According to the Children’s Cancer Hospital Egypt (CCHE), 8500 children in Egypt are estimated to be diagnosed with cancer every year.3 WHO estimated in 2004 that more than 70 percent of all children diagnosed with cancer in the North African region including Egypt are expected to die annually.4,5 The reasons for such a high mortality rate has to our knowledge neither been investigated nor reported in the literature due to the lack of correct and cohesive data and the underreporting of cases.

There are fifteen specialized pediatric cancer wards spread throughout Egypt, yet the major ones are in the capital, Cairo. The National Cancer Institute and three major governmental hospitals in Cairo have served pediatric oncology patients up until 2007 when CCHE, North Africa’s and Middle East’s largest pediatric oncology hospital, opened in Cairo. CCHE is a non-governmental hospital, built and sustained completely by donations. The hospital currently houses 187 inpatient beds, a 300-500 patient capacity outpatient department, a specialized clinical pharmacy, intensive care and bone marrow transplant units, a comprehensive surgery department and multiple special clinics.

CCHEhas an electronic journal system and a research department that generates all kinds of statistics regarding its patients.In CCHE, up-to-date cancer treatment at state-of-the-art radiation and surgery departments are provided. Besides the free of charge health care service offered to the entire country and the compensated transportation to and from the hospital, CCHE also provides the child, upon discharge, with all required medications during the home stay.

This study was undertaken to estimate a five-year survival rate in childhood cancer at CCHE in Cairo, Egypt. Moreover, the study was designed to investigate possible psychosocial predictors of mortality. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg and the Children’s Cancer Hospital research committee.

Study population

The study population comprised one parent of every child newly diagnosed with cancer and admitted to receive the first chemotherapy treatment cycle at CCHE in Cairo, Egypt, during a period of 7months (February until September 2008). Of the 313 eligible parents, 304 (97%) gave their consent to participate.

All parents were approached and asked to answer the questionnaire (Pre-1) at the first day of admission (which was our baseline) either at the day-care center or at the inpatient ward, depending on where the child was planned to receive their first treatment. The same parents were additionally approached for a second questionnaire (Pre-3) upon admission to the third chemotherapy cycle. We excluded parents to children admitted for surgery and radiation therapy only, as they did not fit the inclusion criteria.

Due to the high illiteracy level in Egypt, the study team decided to have an interviewer read the questionnaires to the parents and fill them in. The data collection was performed at CCHE in Cairo, Egypt.

The questionnaires

We constructed two study-specific questionnaires based on 29 in-depth interviews performed by El Malla in 2005 with parents of newly diagnosed children undergoing chemotherapy treatment because of cancer at the pediatric oncology units in three governmental hospitals in Cairo, Egypt. The development and validation of the questionnaires used for this study followed established routines at the Division of Clinical Cancer Epidemiology, which have been described in many articles.6‒8

The two questionnaires were written in colloquial Arabic. To ensure that all questions and response alternatives were fully understood, face-to-face validation were conducted (in spring 2007) with 28 parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer at three governmental hospitals in Cairo, Egypt. The final questionnaires were validated in a subsequent pilot study (in autumn 2007) comprising 54 parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer at CCHE. During this study, we estimated a likely participation rate and checked whether some questions were left unanswered. None of the parents declined participation; thus, we proceeded to the main study.

Both questionnaires (Pre-1: prior to first chemotherapy cycle and Pre-3: prior to chemotherapy cycle 3) consisted of almost 90 questions each. In addition, a Case Report Form (CRF) was filled in from the child’s medical journal prior to our meeting with the parent. The CRF contained the following information: name of child and parent, address, age, gender, length, weight, diagnosis, date of interview, scheduled chemotherapy treatments, medicine received and dose. The two questionnaires were divided as follows: Pre-1: socio-demographic data, cancer diagnosis, family history, the information provided about disease and treatment, hospital stay experience, diagnosis disclosure, communication with physicians and health care professionals, and psychosocial and emotional experiences; Pre-3: reasons for any delay to medical treatment, information provided by health care professionals, side effects of medical treatment, investigations, hospital stay experience, next treatment cycle attendance, adherence to medical treatment at hospital and home, psychosocial and emotional experiences, and trust in the physician, the other health care professionals and the medical care.

For the purpose of this report, data was extracted from both questionnaires and the children’s Case Report Form (CRF). The children were followed up for up to five years from date of entry in 2008.Mortality data was extracted in September 2013 from each patient’s journal in collaboration with the hospital’s medical center. Every patient has its own specific hospital ID that was used when extracting the data, which assures the reliability and accuracy of the data. In the primary analysis, we investigated the survival rates in our study group, and in the secondary analysis, we aimed at identifying psychosocial predictors of survival.

Statistical method

For each outcome we calculated the percentage. Subsequently, the relative risks (RR) were calculated as the ratio of the percentages of each category of the independent variable, together with a 95 percent Confidence Interval (CI). All calculations were performed using SAS for Windows version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Five-year observed survival rate was calculated.

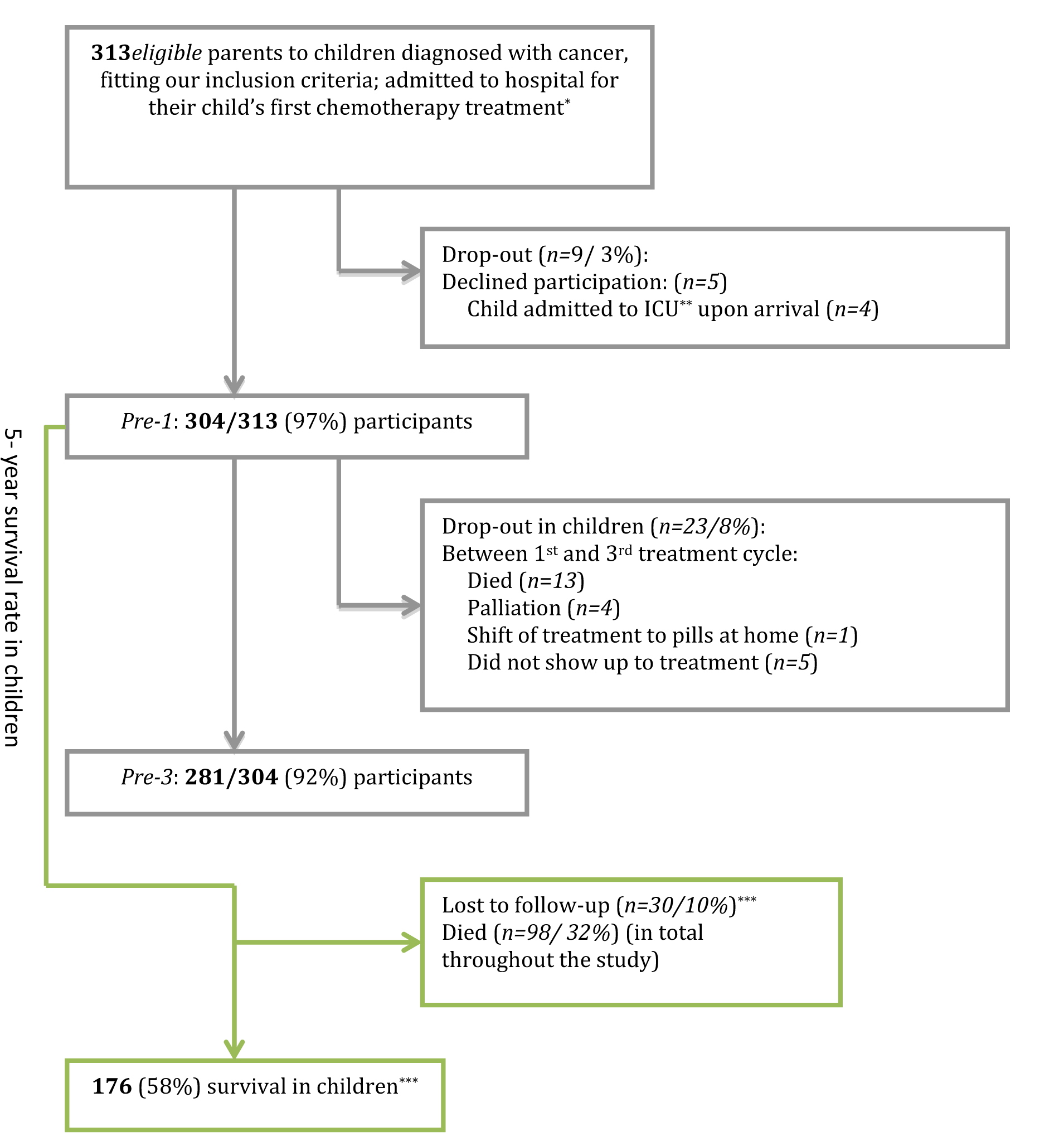

Of the 313 eligible parents to children diagnosed with cancer, 304 (97%) gave their consent to participate (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Study Population.

*One parent of every child

**ICU: Intensive Care Unit

***The survival rates are likely to be between 58% and 68% due to the 10% lost to follow-up

At the time of the second questionnaire, n=281 (92%) of the patients remained in the study, and at 5-years follow-up in September 2013, n=274 (90%) had a known survival status whereas n=30 (10%) of the children were lost to follow-up.

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of the 304children and their parents in our study group, stratified by survival. The majority of the children were in the age group 0-4(44%). Males (59%) dominated and most children had a normal BMI (63%). The majority of the children had both parents as primary caregivers (82%), but the mother was the accompanying parent during the hospital stay (82%). One third of the mothers (30%) and the fathers (30%) did not have any education, whereas more than 10 percent of both mothers and fathers had a university degree. The absolute majority of the mothers (90%) were housewives, and the fathers were laborers (67%). Most of the families lived in rural areas (64%). The majority of the children were diagnosed with leukemia (n=131) followed by lymphoma (n=49), neuroblastoma (n=28), sarcomas (n=25), “other” malignancies (n=20) and brain tumor (n=17). Table 2 describes the survival rate for the different diagnoses. The leukemia and lymphoma patients had the best prognosis, above 70 percent, which corresponded well with Western world figures.

|

Characteristics |

Surviving n (%) (n=176*) |

Total n (%) (n=304) |

|

Age |

||

|

0-4 Years |

78 (44) |

134 (44) |

|

5-8 Years |

39 (22) |

63 (21) |

|

9-15 Years |

46 (26) |

91 (30) |

|

16-18 Years |

13 (7) |

16 (5) |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

Male |

103 (59) |

177 (58) |

|

Female |

73 (41) |

127 (42) |

|

Body Mass Index** |

|

|

|

Under Weight |

37 (23) |

65 (25) |

|

Normal |

101 (63) |

161 (61) |

|

Over Weight |

10 (6) |

20 (8) |

|

Obese |

12 (8) |

17 (7) |

|

Residence |

|

|

|

Urban |

61 (35) |

95 (31) |

|

Rural |

113 (64) |

201 (66) |

|

Abroad |

2 (1) |

8 (3) |

|

Primary Caregiver of the Child |

||

|

Mother |

9 (5) |

18 (6) |

|

Father |

22 (13) |

30 (10) |

|

Both Parents |

145 (82) |

256 (84) |

|

Accompanying/Staying with the Child at the Hospital |

||

|

Mother |

144 (82) |

245 (81) |

|

Father |

27 (15) |

53 (17) |

|

Both Parents |

1 (1) |

2 (1) |

|

Other |

4 (2) |

4 (1) |

|

Mother’s Level of Education |

||

|

No Education |

53 (30) |

106 (35) |

|

Primary/Preparatory |

32 (18) |

58 (19) |

|

Secondary |

33 (19) |

59 (19) |

|

Institute-Diploma |

36 (20) |

48 (16) |

|

University |

22 (13) |

33 (11) |

|

Father’s Level of Education |

||

|

No Education |

52 (30) |

98 (32) |

|

Primary/Preparatory |

25 (14) |

43 (14) |

|

Secondary |

40 (23) |

72 (24) |

|

Institute-Diploma |

39 (22) |

56 (18) |

|

University |

19 (11) |

31 (10) |

|

Not Stated |

1 (<1) |

4 (1) |

|

Mother’s Occupation |

||

|

House Wife |

158 (90) |

275 (90) |

|

Laborer |

7 (4) |

11 (4) |

|

Employee |

11 (6) |

17 (6) |

|

Own Business |

0 (0) |

1 (<1) |

|

Father’s Occupation |

|

|

|

Un Employed |

8 (5) |

18 (6) |

|

Laborer |

117 (67) |

203 (67) |

|

Employee |

43 (24) |

61 (20) |

|

Own Business |

6 (3) |

16 (5) |

|

Not Stated |

2 (1) |

6 (2) |

Table 1 Basic Characteristics of 304 Children

*N=30 patients are lost to follow-up

**BMI from WHO’s guidelines, calculated by age and sex.

|

Diagnosis |

Survival |

|

|

Leukemia |

73% (96/131) |

|

|

Pre-B ALL* |

84% (68/81) |

|

|

Pre-T ALL* |

63% (17/27) |

|

|

AML** |

52% (11/21) |

|

|

JMML*** |

0% (0/2) |

|

|

Lymphomas |

73% (36/49) |

|

|

Non-Hodgkin |

68% (26/38) |

|

|

Hodgkin |

90% (10/11) |

|

|

Brain |

76% (13/17) |

|

|

Medulloblastoma |

75% (6/8) |

|

|

PNET**** |

75% (3/4) |

|

|

Other |

80% (4/5) |

|

|

Neuroblastoma |

39% (11/28) |

|

|

Sarcomas |

48% (12/25) |

|

|

Ewing sarcoma |

45% (5/11) |

|

|

Osteosarcoma |

50% (3/6) |

|

|

Rhabdomyosarcomas |

50% (4/8) |

|

|

Wilms Tumor |

25% (1/4) |

|

|

Hepatoblastoma |

33% (2/6) |

|

|

Germ cell tumor |

43% (3/7) |

|

|

Other |

29% (2/7) |

|

|

Total***** |

64% (176/274) |

|

Table 2 Observed Five-Year Cancer Survival in Study Group

*Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

**Acute Myeloid Leukemia

***Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia

****Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor

*****N=30 children lost to follow-up

We found a five-year survival rate of 58 percent (n=176/304) with a 10 percent lost to follow-up (Figure 1).

Survival was not related to age, gender, BMI, diagnosis, residence, education of fathers and occupation of parents, being late to treatment, adherence to prescribed medication at home, information received at first admission, or trust in the physician, the health care professionals or the medical care in general (Table 3&4). The only factor that was related to survival was the mother’s level of education, P=0.02 (Table 4).

|

Survival vs Death |

No./Total no. (%) |

RR (95% CI) |

No./Total no. (%) |

RR (95% CI) |

|

|

In Time to Treatment |

|

|

|||

|

|

Survivors |

|

Non-survivors |

||

|

Second Cycle |

150/176 (85) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

77/98 (79) |

0.9 (0.8-1.0) >1 |

|

|

Third Cycle |

135/176 (77) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

74/98 (76) |

1.0 (0.9-1.1) |

|

|

Total (Pre-1 to Pre-3) |

123/176 (70) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

63/98 (64) |

0.9 (0.8-1.1) |

|

|

Adherent to Prescribed Medication upon Discharge |

|||||

|

(Pre-3)** |

34/105 (32) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

20/58 (34) |

1.1 (0.7-1.7) |

|

|

Information Received |

|||||

|

Disease (Pre-1) |

117/176 (66) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

63/98 (64) |

1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

|

|

Disease (Pre-3) |

121/174 (70) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

50/82 (61) |

0.9 (0.7-1.1) |

|

|

Treatment (Pre-1) |

124/176 (70) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

59/98 (60) |

0.9 (0.8-1.0) >1 |

|

|

Treatment (Pre-3) |

133/174 (76) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

56/82 (68) |

0.9 (0.8-1.1) |

|

|

Trust |

|||||

|

Medical Care (Pre-1) |

121/176 (69) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

68/98 (69) |

1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

|

|

Medical Care (Pre-3) |

106/174 (61) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

50/82 (61) |

1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

|

|

Health-Care Staff (Pre-1) |

123/176 (70) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

69/98 (70) |

1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

|

|

Health-Care Staff (Pre-3) |

105/174 (60) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

48/82 (59) |

1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

|

|

Doctor (Pre-1) |

127/176 (72) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

76/98 (78) |

1.1 (0.9-1.2) |

|

|

Doctor (Pre-3) |

111/174 (64) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

50/82 (61) |

1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

|

|

Opportunity Communicating with Child’s Doctors |

|||||

|

80/174 (46) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

47/82 (57) |

1.2 (1.0-1.6) <1 |

||

|

Satisfied with the Conversation Style of Child’s Doctors |

|||||

|

101/174 (58) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

48/82 (59) |

1.0 (0.8-1.3) |

||

|

Consider that your Child’s Doctors have been kind |

|||||

|

115/174 (66) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

57/82 (70) |

1.1 (0.9-1.3) |

||

|

Consider that your Child’s Doctors have met with Care |

|||||

|

106/174 (61) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

56/82 (68) |

1.1 (0.9-1.4) |

||

|

Consider that Child’s Doctors are Thoughtful |

|||||

|

86/174 (49) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

45/82 (55) |

1.1 (0.9-1.4) |

||

|

Given Chance Express |

|||||

|

Doctors |

5/174 (3) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

2/82 (2) |

0.8 (0.2-4.3) |

|

|

Nurses |

6/174 (3) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

4/82 (5) |

1.4 (0.4-4.9) |

|

|

Perceived Child’s Doctors as Sensitive to Emotional Needs |

|||||

|

84/174 (48) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

49/82 (60) |

1.2 (1.0-1.6) <1 |

||

|

Perceived Child’s Doctors as to Intellectual Needs |

|||||

|

|

69/174 (40) |

1.0 (Ref.) |

37/82 (45) |

1.1 (0.8-1.5) |

|

Table 3 Psychosocial Differences between the Survivor and Non-Survivor Group

1Less than 1.0

2Before receiving first chemotherapy cycle

3Higher than 1.0

4Before receiving third chemotherapy cycle

|

Demographic Factor |

No./Total no. (%) |

P value* |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

Male |

103/163 (63) |

0.66 |

|

Female |

73/111 (66) |

|

|

Age |

||

|

0-4 |

78/124 (63) |

0.08 |

|

8-May |

39/57 (68) |

|

|

15-Sep |

46/79 (58) |

|

|

16-18 |

13/14 (93) |

|

|

BMI |

||

|

Normal |

102/148 (69) |

0.57 |

|

Underweight |

37/59 (63) |

|

|

Overweight |

10/16 (63) |

|

|

Obese |

12/15 (80) |

|

|

Geographical Area |

||

|

Urban |

61/90 (68) |

0.57** |

|

Rural |

113/180 (63) |

|

|

Abroad |

2/4 (50) |

|

|

Mother’s Level of Education |

||

|

University |

58/75 (77) |

0.02 |

|

Non-university |

65/106 (61) |

|

|

No education |

53/93 (57) |

|

|

Father’s Level of Education |

||

|

University |

58/78 (74) |

0.09 |

|

Non-university |

65/104 (63) |

|

|

No education |

52/89 (58) |

|

|

Mother’s Occupation |

||

|

Employee |

11/16 (69) |

0.68** |

|

Laborer |

7/11 (64) |

|

|

Own business |

0/1 (0) |

|

|

Housewife |

158/246 (64) |

|

|

Father’s Occupation |

||

|

Employee |

43/57 (75) |

0.16 |

|

Laborer |

117/186 (63) |

|

|

Own Business |

6/12 (50) |

|

|

Unemployed |

8/15 (53) |

|

Table 4 Socio-Demographic Factors in Survived and Non-Survived Children and their Parents

At least 58 percent of the children in our study population were still living five years after their cancer diagnosis. The observed survival rates of the children in our study group are substantially higher compared to the official statistics by NCI Egypt and WHO.4,7‒9 To be noted, the observed survival rate may even be higher due to the 10 percent lost to follow-up. Yet, we believe it is unlikely to be much higher than 58 percent as those children who were still alive would have revisited the hospital unless they had moved outside the country. Despite the overall improvements, the survival rates are still lower than corresponding rates in Western countries.

One of the major concerns regarding survival in childhood cancer in Egypt has been the long distance and the lack of transportation to hospitals among rural inhabitants.4,9 Interestingly, we found that the five-year survival rates were the same among rural (63%, 113/180) and urban residents (68%, 61/90). This could to a certain degree be explained by CCHE’s complimentary transportation to and from the hospital and the accommodation offered during treatment if the child lives too far from hospital or is too tired to travel back home. Furthermore, the hospital has established a welfare foundation for financial assistance, i.e. compensation due to reduced working hours/days when the parent is at the hospital for the child’s treatment.

In a previous study we found that parental information sharing is a strong predictor for adherence to medication 10 and trust in the health care professionals and the medical care.11 Hence, we investigated those factors along with other psychosocial and demographic factors to find out if any of those are related to survival.Interestingly, the only statistically significant difference found between survivors and non-survivors in relation to age, gender, BMI, diagnosis, residence, education of fathers and occupation of both parents, being late to treatment, adherence to prescribed medication at home, information received at first admission, or trust in the physician, the health care professionals or the medical care in general was the mother’s level of education P=0.02 (Table 3&4). A large body of empirical evidence support a positive relation between education and health.

CCHE has resources that were not previously found in Egypt such as highly advanced treatment protocols and a holistic cancer treatment offering radiation, surgery and physiotherapy free of charge and available to every child. The hospital has an electronic journal system and offers high technology up-to-date equipment and the treatment protocols correspond to the ones used in the US.

Besides the free of charge treatment provided and the compensated transportation to and from the hospital, CCHE also provides the child, upon discharge, with all required medications (dose adjusted) during the home stay. According to the latest five-year survival rate from CCHE in 2012, the survival rate has increased dramatically and some of the rates have actually reached the survival rates found in Sweden and the US.3

Nevertheless, CCHE only accommodates one-fourth of all diagnosed children with cancer in Egypt, thereforeit may not be representative of the quality of care that is found in other hospitals in Egypt or the rest of the region. Nevertheless, this is the first psychosocial study conducted at CCHE and, to our knowledge, the only prospective study within this field in the Arab World in which data has been collected on more than one occasion and with a five-year follow-up. In summary, we found that mother’s level of education was statistically significant predictor of child mortality at the CCH in Egypt.12‒14

The study group would like to thank all the participating parents in the study. A special appreciation to Professor Dr Sherif Aboulnaga, Dr Samir Abulmagd, Dr Osama Refaat, Dr Mohamad Nasr, Dr Mohamad Ezzat, Dr Mohamad Alshami, and RN Patricia Pruden for their invaluable support during the data collection.

There are no conflicts of interest. All authors have contributed to the manuscript in significant ways and they have all reviewed and agreed upon the manuscript content.

None.

©2017 Malla, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.