Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Research Article Volume 11 Issue 2

Department of Otolaryngolody-Head & Neck surgery, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Talal Al-khatib, Associate professor, Department of Otolaryngolody-Head & Neck surgery, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Tel 00966550574333

Received: March 16, 2019 | Published: March 29, 2019

Citation: Al-khatib T, Haneef SH, Alhusaini OA, et al. Transnasal puncture technique vs endoscopic transnasal choanal atresia repair. J Otolaryngol ENT Res. 2019;11(2):124?127. DOI: 10.15406/joentr.2019.11.00421

Aim: to evaluate the outcome of endoscopic technique for treating choanal atresia (CA) cases as well as to compare it with that of transnasal puncture.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study was performed at the Otolaryngology-Head Neck Surgery department, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, KSA during the period between 2010-2017.

Results: The type of first operation (endoscopic or transnasal puncture) was shown to have a significant relation to the restenosis rate after the first operation (P=0.02), where initial puncture repair had less restenosis rate. On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the two surgical techniques regarding the duration between the first and second operations (p-value=0.064), the required stenting period postoperatively (p-value=0.934), nor the total number of required operations (p-value=0.206). The use of Mitomycin, stents and decongestants had no significant effect on restenosis rate (p-values=0.515, 1.00 and 0.838 respectively).

Conclusion: Endoscopic transnasal choanal atresia repair technique did not prove to be superior to older puncture technique. Stenting had no significant effect on repair outcome. Mitomycin C had somewhat a positive effect on prolonging restenosis. We believe that a transoral endoscopic approach might be superior technique to current transnal technique.

Keywords: choanal atresia repair, transnasal, puncture technique, endoscopic, stent, mitomycin

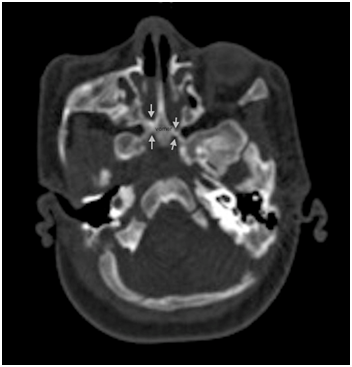

Choanal atresia (CA) is a congenital anomaly arising from failure of canalization of the posterior nasal passage (the choana) which forms the communication between the nose and pharynx.1 Normally, canalization occurs during embryological development between the 4th and 11th weeks of gestation.2 Failure of canalization results in a persistent bucco-pharyngeal membrane or naso-buccal blockage,3 either bony or membranous in structure. CA can occur unilaterally or bilaterally.1,4 Estimated prevalence of CA ranges between 1 per 7000 to 8000 live births. Two-thirds of the cases are unilateral while one third are bilateral. It is twice as common in females.5 Twin pregnancies; chromosomal anomalies and antithyroid treatment during gestation are possible risk factors for CA.6 Since neonates are obligate nasal breathers, bilateral cases are detected at birth due to severe respiratory difficulties and are considered neonatal emergencies. The diagnosis is initiated when a soft catheter cannot pass transnasally, and confirmation is done by a CT scan (Figure 1).1

Figure 1 CT scan of nose and paranasal sinuses showing bilateral choanal atresia (arrowns). Note also thickening of vomer.

Bilateral CA is the most common indication for nasal surgical intervention in infants.7 Unilateral cases usually are detected later in life with complete nasal blockage unilaterally and mucoid discharge. Nasal endoscopy is done to confirm blockage.1 CA is treated surgically by one of three techniques: transnasal puncture, endoscopic and transpalatal techniques. Some surgeons place stents for a period of 6 to 8 weeks. No standard treatment protocol is applied.5 The Ideal approach would be the one able to restore the child’s nasal passage.8 This study aims to evaluate the outcome of endoscopic technique for treating CA cases as well as to compare it with an older technique namely transnasal puncture technique, at King Abdulaziz Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

A retrospective cohort study was performed at the Otolaryngology-Head Neck Surgery department, King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Approval was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, KAUH (approval number 179-17). Patients who underwent endoscopic or transnasal puncture choanal atresia (CA) repair between 2010 and 2017 were included in the study. The following data were extracted from each patient’s medical record: type of CA surgical repair, type of CA (unilateral\bilateral), type of CA seen on computed tomography scan (bony, membranous or mixed), gender, nationality, age at time of first operation, intraoperative and postoperative complications, number of operations needed to cure, use of adjuvant therapy, use of stents, stenting periods and associated congenital anomalies. Statistical analysis was done via SPSS V21 using independent T-test and chi-square test.

Transnasal puncture technique

In this technique, the surgeon would introduce hegar’s dilators through the nasal passage along the floor of the nasal cavity until reaching the choana. A puncture through the atresia is performed. Serial dilation using hegar’s dilators of various sizes until a large size dilator can go through. A 3.5 endotracheal tube is used as a stent in a U-shaped fashion with both ends coming through anterior nares. The stents are then removed in the operating room six weeks later.

Endoscopic transnasal technique

In this technique, the surgeon introduces a 2.9mm endoscope through the nasal cavity. Identification of choanal atresia is then performed. Using a straight suction, a puncture is performed anterior-inferiorly close to the vomer bone of the nasal septum (Figure 2A). Visualization of adenoid pad in the nasopharynx assures proper puncture through atresic palte and not into soft palate (false passage). The opening is then enlarged using a drill or shaver depending on the thickness of the atretic plate (Figure 2B, Figure 2C). A mucosal flap is usually not possible to preserve by the end of the procedure. The other choana atresia side is addressed similarly. Lastly, the vomer is removed using a backbiter forceps. Two size 3.5 endotracheal tubes are used one in each side and tied together anteriorly using a sub-labial suture for fixation to avoid collumellar pressure. The stent are removed in the clinic six weeks later.

We identified 36 patients who underwent choanal atresia repair at KAUH. After reviewing the records, 2 patients were excluded because the repair was transpalatal approach and 4 due to incomplete records. 30 children operated for CA repair during the 7-year period between 2010-2017 were studied. Their ages ranged from 3 days to 7 years. 30% of the sample were males and 70% females, significantly higher incidence than males, (P-value=0.028). Associated congenital anomalies were found in 17 of cases (56.7%), including, but not limited to: CHARGE syndrome, cleft palate, patent ductus arteriosus, heart defects and malformations of the nose and pharynx. 22 (73.30%) of patients were from Asian ethnicity, while 8 (26.70%) were from African ethnicity and none of Caucasian, showing significant association between ethnicity and CA (P-value=0.011).

Regarding the type of atresia, the incidence of bilateral cases was significantly higher than unilateral (p-value=0.011). 22 patients had bilateral CA, 14 of which were females and 8 were males. Of the bilateral cases, 6 (27.3%) had bony type. Nine (40.9%) had membranous type and 5 (22.7 %) had mixed type, as diagnosed by CT scan. The age range for initial surgery was between 0.10 to 51 months for bilateral cases, and most of them required the use of stents (20 patients, 90%). 40.9% of bilateral cases were asymptomatic after the second operation, and only 3 had intraoperative complications, including: small injury to the soft palate and columellar separation (the separation was a complication of the first operation that was done elsewhere).

8 patients had unilateral CA, 7 of which were females and 1 was male. Of the unilateral cases, 2 had bony type (25%), 4 had membranous type (50%), 1 had mixed (12.5%) type and 1 had no identified type on CT scan. The average age for initial surgery was 36.38 months (range 67 to 72 months) for unilateral cases, and a smaller percentage of them required the use of stents (8 patients, 75%) as compared to those with bilateral CA. 37.7% of unilateral cases were asymptomatic after the 2nd operation. There was neither difference in restenosis rates nor the incidence of associated congenital anomalies between unilateral and bilateral CA. Generally, the incidence of membranous type of CA was the highest compared to bony and mixed types. Table 1 summarizes the differences between unilateral and bilateral cases.

|

Unilateral CA |

Bilateral CA |

N |

8 |

22 |

Gender |

Male:1 |

Male:8 |

Female:7 |

Female:14 |

|

Mean Number of operations |

1.88 |

1.95 |

SD 0.835 |

SD 1.214 |

|

Use of stents |

6(75%) |

20(90%) |

Type of CA |

Bony:2(25%) |

Bony:6(27.3%) |

Membranous:4 (50%) |

Membranous:9(40.9%) |

|

Mixed:1(12.5%) |

Mixed:5(22.7 %) |

|

Missing:1 |

||

Type of 1st surgery |

Endoscopic:4(50%) |

Endoscopic:9(40.9%) |

Puncture:4(50%) |

Puncture:13(59.1%) |

|

Restenosis |

5 |

12 |

Congenital anomalies |

5 |

12 |

Table 1 Comparison of unilateral and bilateral cases of Choanal atresia

In regards to surgical technique, 13 patients (43.30%) initially underwent endoscopic surgery. 4 had unilateral CA (30.7%) and 9 had bilateral CA (69.2%). Removal of vomer was done in 2 patients, puncture in 1 patient and flap in 1 patient. 12 of those patients (92.3%) had stents placed after the first endoscopic operation; with average stenting duration of about 14 days. 11 patients (84%) had restenosis. There was no significant difference in restenosis rate between unilateral and bilateral cases undergoing initial endoscopic repair (p-value=0.848). Patients required about 2 operations on average when the initial surgery was endoscopic (total number of required operations M=2.23, SD=1.36, range 1-6). Adjuvant therapy was used in 10 patients postoperatively (76.9%) and had no significant effect on restenosis (p-value=0.994). The durations between the first endoscopic operation and the following operation had a mean of 4.2 weeks (SD=4.73 [0.3-15]).

17 patients (56.70%) initially underwent transnasal puncture surgery, 4 of which had unilateral CA (23.5%) and 13 had bilateral CA (76.4%). 14 (82.4%) had stents placed postoperatively, with average stenting duration of about 14 days. 6 patients (35.3%) had restenosis. There was no significant difference in restenosis rate between unilateral and bilateral cases undergoing initial transnasal puncture surgery (p-value= 1.00). Patients required about 2 operations on average when the initial surgery was transnasal puncture (total number of required operations M=1.71, SD=0.84, range 1-4). Adjuvant therapy was used in 13 patients postoperatively (76.5%), and had no significant effect on restenosis (p-value=1.00). The durations between the first transnasal puncture operation and the following operation had a mean of 14.1 weeks (SD=14.27 [1-48.5]). Regarding complications, 1 patient who underwent puncture surgery had small injury to the soft palate.

The type of first operation (endoscopic or transnasal puncture) was shown to have a significant relation to the restenosis rate after the first operation (P=0.02), where initial puncture repair had less restenosis rate. On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the two surgical techniques regarding the duration between the first and second operations (p-value=0.064), the required stenting period postoperatively (p-value= 0.934), nor the total number of required operations (p-value=0.206). Table 2 summarizes the differences between the two techniques.

Frequency |

Endoscopic |

Puncture |

Number of Operations |

13 |

17 |

Mean number of operations |

2.23 |

1.71 |

Types of operated CA |

Unilateral:4(30.7%) |

Unilateral:4(23.5%) |

Bilateral:9(69.2%) |

Bilateral:13(76.4%) |

|

Use of stents |

12(92.3%) |

14(82.4%) |

Restenosis |

11(84%) |

6(35.3%) |

Adjuvant therapy used in |

10(76.9%) |

13(76.5%) |

Table 2 Comparison between endoscopic and puncture techniques

Mitomycin C was used as an adjunct therapy to surgery in 10 patients (33.3%). It made no significant difference in the outcome when compared to those not used on, based on the total number of required operations, the duration between 1st and 2nd operation and restenosis rates (p-values=0.071, 0.083 and 0.515 respectively). Topical decongestants were applied also as adjunct therapy to surgery in 11 patients (36.6%). Decongestive agents that were used are: xylometazoline, mometasone furoate monohydrate and dexamethasone Na Phosphate. It had no significant effect on the outcome (the total number of required operations, the duration between 1st and 2nd operation and restenosis rates [p-values=0.209, 0.252 and 0.838 respectively]).

Postoperative intranasal stents were placed in 26 patients (86.70%). Longer stenting durations followed the first operation (M=14, SD=9.73 days). After the second operation, the mean stenting time in days=7.7, and SD=5.9. Shorter stenting periods followed the third and fourth operations (7 and 5 days, respectively). The overall average stenting period was about 14 days. However, there was no significant effect on restenosis rate with the use of stents (p-value=1.00) nor with stenting period (p-value=0.446).

Chaonal atresia (CA) is treated surgically by one of three techniques; the first is transnasal puncture using Hegar dilators. Second is endoscopic technique using endoscopic instruments, shaver and/or drill. And lastly transpalatal technique. No standard treatment protocol is applied.5 In recent years, the intranasal endoscopic route has displaced the classical palatal pathway, as it less invasive and provides excellent results, offers good visualization and avoidance of midpalatal suture with less blood loss, and no risk of palatal fistula or stunted palatal growth.5,9–11

We have found that the revision rate after initially undergoing endoscopic repair was 84%, which is high in comparison to that after initial puncture repair (35.3%). It was previously suggested that recurrence rates of endoscopic repair were higher when compared to those of transpalatal approach as well, which can be explained by the technical difficulty due to the small nasal cavities of neonates.5 Although, revision rates as low as 21% have been reported.12 Some authors consider the second surgery as “touch up” or stents were removed in the operating room but is not counted as revision or failure.

Some authors use topical Mitomycin C as an adjuvant therapy post-operatively to prolong nasal patency by preventing scar tissue growth.13 We found no significant effect to its use on the outcome of our study, based on the number of operations, the duration between the first two surgeries, and restenosis. Although this can be attributed to the small sample size, since the p-values were close to being significant. Similar results supporting the insignificance of Mitomycin use were reported by proceeding authors.14,15 Some authors haven’t included mitomycin in their therapy plan and had an excellent success rate.13 On the other hand, a study on 114 CA patients reported a significant association between the use of Mitomycin and a greater number of required operations (3.31 vs 2.01;P<.001), yet no association was found in terms of patency.16 Poorer outcome association with the use of Mitomycin was observed in other studies as well; since it’s used to manage refractory atresia.17,18 To the contrary, a retrospective review on 17 patients demonstrated the efficacy of Mitomycin on many aspects. It was associated with less formation of granulation tissue, less restenosis and fewer surgeries.19 A systemic review comparing five articles and a total of 155 cases support the previous study. The rate of restenosis was less in those who had mitomycin applied compared to those who hadn’t, with the percentages 24.28% and 35.29% respectively.20 Due to this discrepancy of data in literature, the adoption of mitomycin as an adjuvant therapy is still controversial as prospective studies on its efficacy are yet to be done.

Some surgeons use Stents during the post-operative period to stent the neochoana. It is believed by some that stents prevent re-stenosis by promoting the formation of adequate fibrous tissue.8There’s an ongoing debate on the benefits and risks of stenting post CA repair. The risks of placing stents include: nasal mucosal damage caused by excess pressure, bacterial overgrowth, granulation tissue, scar formation and blockage of mucus drainage.11 Stents were utilized in most of the patients included in this study [26 patients (86.70%)]. We found no difference in the outcome whether stents were implemented or not. A similar outcome was observed in a case series of 43 patients operated endoscopically, where stenting did not affect the outcome.12 A previous study, which included 10 patients who underwent nasal endoscopic surgery without using stents on any of them, have reported a success rate of 100% and no complications.13 On the other hand, another study included 49 patients with CA whom underwent transnasal endoscopic repair with placement of stents to all of them. 7 patients out of the 49 developed stent related complications, and good nasal ventilation was eventually achieved in 93.9%.11 The mean durations of stenting described in literature varied, ranging from as short as 48hours to as long as 16 weeks.21 Some have suggested that shorter durations of stenting (5-7days) aid better outcome, while others proposed that longer periods (up to 12 weeks) are necessary,12 although stenting durations weren’t found to significantly alter revision rates.12,21,16 Similarly in our study (with average stenting period of two weeks) we found no significant effect on the outcome by prolonged stenting.

Transnasal approach in newborns was not superior to puncture technique perhaps due to small working area inside neonatal nasal cavity. We think that a transoral endoscopic approach might provide better working space and lager instruments can be accommodated. A detailed description of the technique along the patented instruments is described in our previous publication.22

Endoscopic transnasal choanal atresia repair technique did not prove to be superior to older puncture technique. Stenting had no significant effect on repair outcome. Mitomycin C had somewhat a positive effect on prolonging restenosis. We believe that a transoral endoscopic approach might be superior technique to current transnal technique.

We would like to thank and acknowledge dr. Khalel Sendi, retired ENT surgeon, as some of the trans nasal puncture technique cases were his.

Author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2019 Al-khatib, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.