Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Case Report Volume 2 Issue 1

ENT Department, Canberra Hospital, Australia

Correspondence: Rahuram Sivasubramaniam, ENT Outpatients Department, Level 2, The Canberra Hospital, Yamba Drive, Garran, ACT 2605, Australia, Tel +61 2 62442222

Received: January 10, 2015 | Published: January 21, 2015

Citation: Sivasubramaniam R, Choroomi S, Stone HE. Sialolithiasis in a remnant wharton’s duct: a case study and discussion. J Otolaryngol ENT Res. 2015;2(1):51-53. DOI: 10.15406/joentr.2015.02.00012

A common indication for removal of the submandibular gland is recurrent infection due to the presence of a stone (sialolith) in Wharton’s Duct. We present a case of infection due to sialolithiasis in a remnant of Wharton’s duct, 11years after removal of the submandibular gland. A literature review of this unusual condition and various management options in treating submandibular sialolithiasis has been performed and discussed. Stones may be present and become symptomatic in remnant Wharton’s ducts, either remnant from original surgery or via de novo formation. We suggest that patients undergoing submandibular gland excision for sialolithiasis should be made aware of this.

Keywords: wharton’s duct, sialolothiasis, sialolith, submandibular

Sialolithiasis is a common disorder affecting an estimated 12 in 1000 people each year and it accounts for more than fifty percent of the salivary gland diseases.1 Although it can be found in children, it more commonly affects adults in their third to sixth decades.2 There is a male predominance in sialoliths with some authors quoting that over 80% of the salivary calculi occur in the submandibular gland and less than 20% occurs in the parotid gland.3 The sublingual and minor salivary glands are rarely affected. The great majority of the stones in the submandibular gland are located in the Wharton’s duct, with a ratio of 7:3 compared to intraglandular stones.4 In this paper, we present a case of a Wharton’s duct stone presenting with pain and swelling in the submandibular region and floor of mouth in a female patient who has had her submandibular gland removed 11years prior to presentation.

36 year old female presented with right sided submandibular area and floor of mouth pain, swelling and tenderness to the emergency department in a tertiary hospital. She had been experiencing these gradually worsening symptoms for 24-36hours prior to presentation. Her background medical history showed previous right submandibular gland resection for sialolithiasis 11years ago. She had nil other significant medical issues. On examination she had pain and tenderness over the submandibular triangle and also had a tender focal swelling in the floor of mouth on the right side, possibly representing a stone. She was organised to have a computerised tomography (CT) scan done along with an orthopantomogram (OPG) x-ray. She was admitted to the hospital for intravenous antibiotics and analgesia.

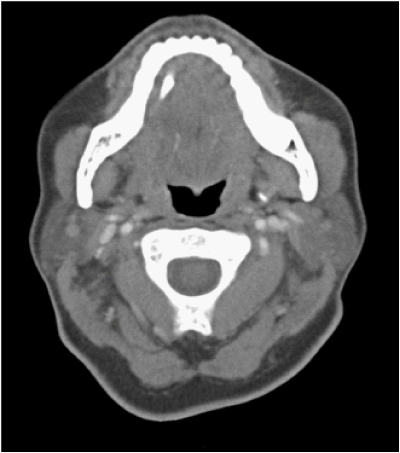

The CT showed a calculus in the region of distal submandibular duct measuring 5 X 3 X 13mm and evidence for acute inflammation (Figures 1&2). On further history taking, she has had no such similar episodes since the removal of her right submandibular gland and this was her first attack. She has also not noted any lump in her floor of mouth or neck in the past.

Figure 1 Computerised Tomography (CT) scan image of the patient showing the stone in the Wharton’s duct.

Figure 2 Computerised Tomography (CT) scan image of the patient showing the stone in the Wharton’s duct.

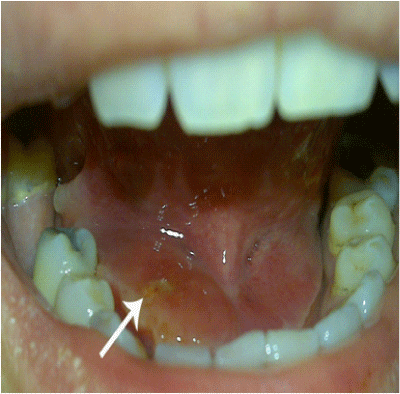

On day one of admission, she passed the stone out without any surgical intervention, leaving a dilated opening of the Wharton’s duct in the floor of mouth (Figure 3). The stone was yellow, firm with relatively smooth surface. The stone was 17 X 4 X 3 mm and was “olive-pit” shaped, almost fitting the shape of the duct (Figure 4). This appearance is similar to the normal ductal sialoliths in patients with submandibular gland. Since the stone had passed, she clinically improved and was later discharged home.

Figure 3 Photo of the patient’s floor of mouth showing the dilated opening of the Wharton’s duct after the stone had passed.

We explained the scientific importance of her disease and presentation and obtained her consent for the case study.

Salivary gland stones are not an uncommon occurrence in the population; however the exact cause of the formation of sialoliths remains unknown. The formation of sialolith is a multifactorial event, in which disturbances in secretion, microliths and bacteria may play the major role. The nuclei of the sialolioths are mostly made of inorganic materials such as calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate, but some studies have shown that the nidus could be bacterial matter as well.5 Surrounding this nucleus are the laminar layers of both organic and inorganic substances and this content varies within a single sialolith. The outer shell is coated by the organic materials such as glycoproteins, mucopolysaccharides, lipids and cell detritus. Teymoortash et al.,6 looked at the mineral composition of sialoliths in different parts of the ductal system and observed that there was a higher concentration of the whitlockite crystals in the stones in the Wharton’s duct compared to intraglandular ducts and this could be due to the higher concentration of calcium and phosphate in the saliva of the Wharton’s duct.6

In our case, we have sialolith in the Wharton’s duct where there was no remnant submandibular gland on that side. Thus, the pathogenesis of this stone is difficult to ascertain. One explanation is that the stone could have been present in a much smaller size at the time of her initial surgery for removal of submandibular gland and had grown in size over the past 11years. It is well documented that a stone grows by about 1 – 1.5mm each year However, in this patient for this to occur, she must have had some retrograde flow of saliva from the mouth.7 in to the Wharton’s duct to allow the stone to increase in size. Studies have shown that 90% of salivary ducts in the distal 3cm had a sphincter like mechanism and this could allow for retrograde migration of oral material.8,9 The other possibility is that the stone could have developed in the duct de novo after the gland was excised. In this case, the nucleus could have been present from before or could have developed secondary to a subclinical infection in the duct and the subsequent layering of the nucleus was aided by retrograde flow of saliva into the duct. Further investigation and research is needed to better understand the pathogenesis of intraductal sialolith post removal of the salivary gland.

Management of salivary gland stones have been widely discussed in recent literature, however this finding of ductal stones after resection of the gland brings an added element in to the variety of available treatment for sialolithiasis. Gland preservation is recommended in several new trials due to studies showing normal histologic finding in submandibular glands resected for sialolithiasis and also salivary scintigraphy performed before and 6 months after stone removal has shown return of secretory function to normal.10 There have been multiple methods described in the literature for removal of intraductal sialolioths without removal of the gland according to their location in the duct. In our case, a transoral sialodochoplasty would have been sufficient, however the other modalities could have included interventional sialendoscopy with wire-basket extraction or a combined approach as described by Marchel et al.,11,12 It is important to note that there is also evidence to show that salivary flow rate decreases following stone formation and even after removal of the stone, placing the gland at risk for recurrent infections and stone formation.13 Thus, in the case of recurrent sialadenitis and or intraglandular stones, submandibular gland removal is still widely performed and recommended.14 In most cases scans are performed prior to surgery to assess for presence of obvious sialolith in the duct, however a small nidus would be impossible to pick up in these scans. Thus, we believe it is important to recognise that sialoliths can develop in remnant Wharton’s duct and should be considered when a patient presents with submandibular or floor of mouth inflammation with previous history of submandibular gland resection.

This case summarises that even in patients with prior removal of submandibular gland, they can develop sialoliths in the remnant Wharton’s duct and subsequently get infected and cause symptoms years after initial surgery. We believe that there are only few published case studies on such presentation and that this further adds to the importance of considering such scenario when reviewing a patient presenting with such symptoms.15

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2015 Sivasubramaniam, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.