Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Research Article Volume 14 Issue 3

Surgical Clinical Teaching Hospital, Havana, Cuba

Correspondence: Dr. Ivonne Delgado Juan, Surgical Clinical Teaching Hospital, Havana, Cuba, Tel +5930996991411

Received: September 17, 2022 | Published: December 9, 2022

Citation: Juan ID, Alfredo L, Regalado R. Esophageal foreign bodies. J Otolaryngol ENT Res. 2022;14(3):103-106. DOI: 10.15406/joentr.2022.14.00515

Esophageal foreign bodies are a relatively frequent emergency in our country and their removal is necessary as quickly as possible to avoid complications and suppress the discomfort they cause to patients, so an emergency esophagoscopy is performed by the Otolaryngology Specialist who is is on duty, so all otolaryngologists must know this entity and have experience in the diagnosis and performance of the surgical technique for its extraction, wanting with this exhibition to contribute to have a better knowledge of this entity.

Keywords: foreign body, esophagus, dysphagia

Foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus are a relatively frequent emergency in our country due to the increase in the intake of alcoholic beverages with the intake of poultry and pork. Ingestion is usually accidental or involuntary and only in patients with mental disorders and in children is it done voluntarily.1

The esophagus is a vertical muscular tube that in the adult measures 23 to 25cm and extends from the lower border of the cricoid cartilage above, to the level of the sixth cervical vertebra, passes through the neck and the superior and posterior mediastinum through in front of the cervical and thoracic vertebrae, and ends at the level of the cardia in the stomach, at the level of the eleventh thoracic vertebra. It passes through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm at the level of the tenth dorsal vertebra together with the vagus nerves and some small esophageal vessels.2–4

The esophagus in its course through the neck and thorax is related to several structures:

In the neck: Ahead: the trachea and the two lobes of the thyroid gland, with the largest contact area with the left lobe due to the deviation of the esophagus to the left at that level. From behind: the vertebral column, separated by the long muscles of the neck and the prevertebral aponeurosis. On each side: the carotid sheath and its contents, and the lobes of the thyroid gland. The recurrent laryngeal nerves ascend in the groove between or slightly anterior to the esophagus and trachea.

In the thorax: In front: the trachea, the left main bronchus, the pericardium and the diaphragm. Behind: the vertebral column, the thoracic duct, the azygos veins and the terminal parts of the hemiazygos veins. It rests on the anterior part of the descending thoracic aorta, below, near the diaphragm. On the left side: the aortic arch, the left subclavian artery, the thoracic duct, and the left pleura. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve travels up the groove between the esophagus and the trachea. On the right side: the right pleura in its entire length and the azygos vein. The vagus nerves descend in close contact with the esophagus, below the hilum of the lung, the right one preferentially behind it and the left one in front.

The esophagus has four layers. The mucosal layer: lined by a thick non-keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium. The muscularis mucosa appears to be a continuity of the epithelium and takes the place of the elastic layer of the pharynx. The submucosal layer consists of thick elastic and collagen fibers, contains mucous glands and Meissner's plexus. The muscular layer in its upper third contains only striated muscle, the middle third, striated and smooth, and the lower third only smooth muscle. This in turn has 2 layers: the internal circular that is continuous above with the inferior constrictor muscle of the pharynx (cricopharyngeal sphincter) and the external longitudinal: it forms a complete cover except at its upper end, on the back (Triangle of Lamier) where these fibers leave a gap because they divide into three fascicles, one is inserted anteriorly to the cricoid cartilage and the other two on each side are continuous with the pharyngeal musculature. Between both muscle layers is the Auerbach's mesenteric plexus. And finally the external fibrous layer formed by a loose fibroelastic tissue 5–12

The esophagus participates in the involuntary phase of swallowing. When the pharyngeal constrictor muscles contract, the upper esophageal sphincter (cricopharyngeal muscle) relaxes, thereby propelling food into the esophageal lumen, initiating peristalsis. The cricopharyngeal muscle functions as an upper esophageal sphincter, being a transitional segment between the pharynx and esophagus, usually maintained in a constant state of contraction, relaxing at the moment of swallowing in a short period of time of 0.5-1.2 seconds. During which the food bolus enters the esophagus. The lower esophageal sphincter is a high-pressure area of the 2 to 4cm in length that prevents gastroesophageal reflux by relaxing during swallowing, being formed by the complex interaction of a series of anatomical and physiological factors and its function being regulated by a set of interrelated muscular and hormonal mechanisms.

The voluntary or oral phase represents the first phase of swallowing, during which the food bolus is pushed towards the pharynx, being in the pharynx it activates the oropharyngeal sensory receptors, initiating the swallowing reflex or involuntary phase. The bolus is pushed backwards by the tongue, the larynx moves forward and the upper esophageal sphincter opens. When the bolus enters the esophageal lumen, peristaltic waves are triggered, which are responsible for propelling food to the lower esophageal sphincter. Which remains open until the wave ends.7–9,12

The cricopharyngeal muscle relaxes and contracts periodically, a dilation and closure seen through an esophagoscope placed behind the cricoid cartilage. The constrictions of the aortic arch and the left mainstem bronchus are not easily observable by endoscopy. The diaphragmatic hiatus appears as an oblique narrowing of an anterior situation that, when exceeding it, the star-shaped shape of the esophagus disappears, observing the red gastric mucosa with its grooves or prominent wrinkles.

The constrictor muscles of the pharynx are very powerful and can propel bulky and irregularly shaped objects into the esophagus, and since muscle activity in the lower part of the esophagus is very weak, there is a good chance that the foreign bodies are lodged immediately below the esophagus. cricopharyngeal muscle. Thus we see that most of the esophageal foreign bodies are located in the upper third at the cricopharyngeal level, some publications mention 60-70% and others that up to 95% can remain embedded in this location, followed in order of frequency the lower third, in the gastroesophageal junction with 10-20% and in the middle third in the constrictions generated by the aortic arch and the left main bronchus only 10-15%.1,2,4,5,8,9

Esophageal foreign bodies are classified as organic and inorganic. The organic ones are made up of meat, thorns or bones and the list of inorganic ones is infinite such as coins, buttons, needles, safety pins, dental prostheses, etc. Regardless of the nature of the foreign body, it tends to stop at anatomical narrowing of the esophagus or pathological strictures.

Foreign bodies in the esophagus are usually observed in young children, since the possibility of this accident taking place exists every time the child puts an object in the mouth. The penetration of foreign bodies also occurs frequently in the elderly, especially among the edentulous or those who wear dental prostheses who are less sensitive to the presence of bones or other non-swallowable objects in food. Also, any pre-existing esophageal disease, particularly strictures, predisposes to the retention of foreign bodies, just as on occasions, the food itself that has not been carefully chewed becomes a foreign body. People with mental disorders and drunkards are especially exposed to the ingestion of foreign bodies.

In adult patients, after ingesting the foreign body, dysphagia clinically occurs, making it impossible to swallow, including saliva, odynophagia or retrosternal pain, in the back or in both places, sialorrhea and/or sensation of a foreign body or discomfort at the cervical or retrosternal. Dysphagia and hypersalivation are suggestive of foreign body entrapment in the esophagus. When they are rough or pointed, they can cause abrasion or tear of the pharynx or esophagus and pass through the gastrointestinal system, in which case the pain caused by swallowing subsides after 24 hours10–14

Sharp foreign bodies are likely to cause esophageal perforation, which can take place initially or after about 24 hours of permanence of the foreign body in the esophagus, presenting the patient with fever, tachycardia, crepitus and cervical swelling. "The longer a foreign body is retained in the esophagus, the more likely it is that perforation will occur".

Respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, and stridor suggest that the foreign body is trapped in the hypopharynx, pyriform sinus, or may be so large that it causes extrinsic compression of the trachea through its posterior membranous wall.

The history is of paramount importance. The patient presenting with a history of ingestion of a non-chewable substance places the physician in the position of having to ascertain whether or not the substance has been retained.

As a physical examination, an examination of the ENT specialty is performed with oropharyngoscopy and indirect laryngoscopy to first rule out that the ingested foreign body is in the oropharynx or hypopharynx and in the indirect laryngoscopy an accumulation of saliva can be observed in the pyriform sinuses called the sign of Chevalier Jackson indicating that there may be an obstruction in the esophageal lumen. On examination of the neck, crepitus may appear due to subcutaneous emphysema and swelling if there is esophageal perforation.

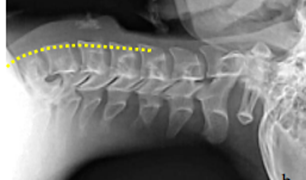

For the diagnosis, in addition to the symptoms, a radiographic study is performed. When it comes to radiopaque foreign bodies located in the cervical portion, they are identified with a simple lateral neck radiograph (Image 1) and when they are found in the thoracic portion, posteroanterior, lateral, or oblique simple chest radiographs are performed (Image 2). These same radiographs show evidence of non-opaque foreign bodies in the esophagus in the form of an increase in the distance between the cervical vertebrae and the larynx or trachea, or by the presence of air inside the esophagus. If nothing is found in this way, a contrast study of the esophagus should be performed, using a small cotton swab saturated with a suspension of barium sulfate or a water-soluble radiopaque solution, The same radiographic views are made and the stoppage of the swab inside the esophagus is observed (Images 3) (Image 4). Frequently, the patient continues to have the sensation that the foreign body persists despite the lack of radiographic evidence that this is the case. In these cases, the possibility of the presence of a foreign body must be excluded by esophagoscopy after the first 24 hours.15–18

Image 3 & Image 4 The same radiographic views are made and the stoppage of the swab inside the esophagus is observed.

Once the diagnosis of an esophageal foreign body has been made, its extraction must be carried out as quickly as possible to avoid complications such as esophageal perforations and the edema that the foreign body itself can produce, making extraction difficult, so as the Golden Rule ¨every esophageal foreign body must be removed or attempted to be removed urgently.

Esophagoscopy for foreign body removal is performed with a rigid (open-tube) esophagoscope or with a panendoscope or flexible esophagoscope. In our specialty we use the traditional method of extraction by rigid esophagoscopy under general anesthesia and on occasions they are extracted with flexible esophagoscopy under local anesthesia performed by gastroenterologists, although the diagnosis is always made by otolaryngologists.19–22

Rigid esophagoscopy technique.23

A perforation of the esophageal wall with a rigid esophagoscope is a life-threatening event. Therefore, rigid esophagoscopy must be performed with extreme caution and finesse; this requires clinical judgment as to when to abandon the procedure or call for expert assistance.

Figure 1 The proximal esophagus follows the lordosis of the cervical and thoracic spine; keep the cervical spine in a straight line with the thoracic spine elevating the head.

In some cases, the foreign body cannot be removed by esophagoscopy and it is necessary to perform a surgical intervention that can be: cervicotomy, thoracotomy or laparotomy, depending on its location.

Most complications from esophagoscopy for foreign body removal are due to inexperience in inserting the esophagoscope or in pulling on the presenting part of the foreign body without first determining the consequences that traction might cause. Complications are serious when they occur, although they are rare and have been controlled more quickly since the advent of antibiotics. Non-perforating ulcerated lesions or tears of the esophageal mucosa and esophageal perforations are mentioned as the most frequent, for which cervical mediastinotomy is indicated. Paraesophageal emphysema, cellulitis or neck abscess, mediastinal emphysema, mediastinitis or mediastinal abscess, pneumothorax, edema of the larynx, perforation of the aorta, tracheoesophageal fistula and sepsis.24–30

Esophageal foreign bodies are a frequent pathology in emergency services in our country. Early diagnosis and immediate control are essential to ensure appropriate treatment. Diagnosis is made through simple or contrast radiology. The treatment of choice in our specialty is rigid endoscopy. Open surgery is limited to endoscopic failures or complications.

None.

None.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

©2022 Juan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.