Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Case Report Volume 7 Issue 3

Department of Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery India

Correspondence: ID Singh Department of Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery India, Tel +91-7767834137

Received: April 04, 2017 | Published: May 30, 2017

Citation: Singh ID, Galagali JR (2017) Cervical Vagal Schwannoma Presenting as Paroxysmal Cough-A Case Report. J Otolaryngol ENT Res 7(3): 00206. DOI: 10.15406/joentr.2017.07.00206

schwannomas, peripheral nerve tumours, diagnosis, treatment, mr evaluation

Schwannomas are rare peripheral nerve tumours; about one third occur in the head and neck region. Clinically, they present as asymptomatic slow-growing lateral neck masses that can be palpated along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Approximately half of the reporte parapharyngeal schwannomas arise from the vagus nerve. Most schwannomas of the vagus nerve are benign tumors. Most cases of schwannomas manifest between the third and sixth decades of the patient’s life as a slow growing firm, painless mass in the lateral neck. Hoarseness, pain, or cough may be the presenting complaints. They displace the carotid arteries anteriorly and medially, jugular vein laterally and posteriorly. These swellings are mobile transversely but not vertically. In symptomatic patients, the most common complaint is hoarseness and coughing, which can be revealed during palpation of the mass.

The cough is caused by stimulation of afferent vagal nerve endings due to prominent cystic degeneration of the tumour. This clinical sign is quite specific for cervical vagal schwannomas. A preoperative diagnosis of vagal schwannoma may be difficult, and is often not made up to the time of surgery. However, diagnostic techniques in the form of FNA and imaging modalities, including computed tomography (CT) and MRI scans, have lessened the problem of misdiagnosis to some degree. On imaging, anterior displacement of the common or internal carotid artery is a characteristic finding of parapharyngeal neurogenic tumors. On CT images, vagal schwannomas appear as well-defined masses, usually of higher attenuation than muscle on contrast-enhanced images. MR evaluation typically shows masses of intermediate signal on T1-weighted images and increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images with smooth, well-delineated margins and a homogeneous overall appearance. Occasionally, necrosis and cystic degeneration are seen.

A 37year old male presented with complaints of Swelling (R) side of the neck for the past 2years, which was a n insidious onset, slow growing swelling. There was a history of paroxysmal cough for last one year and the cough could be elicited when the swelling pas palpated (Figures 1 & 2). There was history of mild voice change but no hoarseness or respiratory distress. There was no history of dyspnea, dysphagia, dysphonia, odynophagia, syncope/giddiness, palpitation, and tingling sensation in upper limb. There was no hypertension. On examination there was a 5x6cm swelling on the (R) side of the neck which extended from the angle of the mandible to the thyroid notch. It was a non tender, firm swelling which was mobile in the horizontal axis but immobile in the axis of the Sternocleidomastoid muscle of that side.

Figure 1-2 N=57; Epidemiological distribution of the pathological fractures, traumatic fractures, and nonunion.

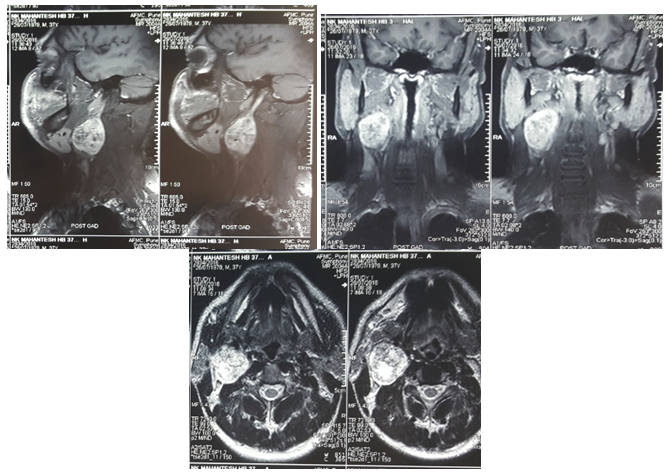

There was no other swelling palpable over the neck and the rest of the examination of the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx and ear were normal. The Hopkins Rod exam showed bilateral vocal cord mobility with slight sluggishness on the right side. The urine tests were negative for VMA and metanephrines. The USG of abdomen was normal. An MRI was done of the neck with showed a 5cm lesion in the (R) carotid space. It was displacing the sternocleidomastoid muscle laterally and displacing the external and internal carotid arteries anteromedially without spying the carotids. The (R) Internal Jugular Vein was compressed and displaced laterally by the mass. The features on imaging were suggestive of a schwannoma of the vagus nerve (Figures 3-5).

Figure 3-5 Contrast MRI-Smooth marginated mass right carotid space with anterolateral displacement of ECA, ICA & IJV but not splaying of the ECA and ICA.

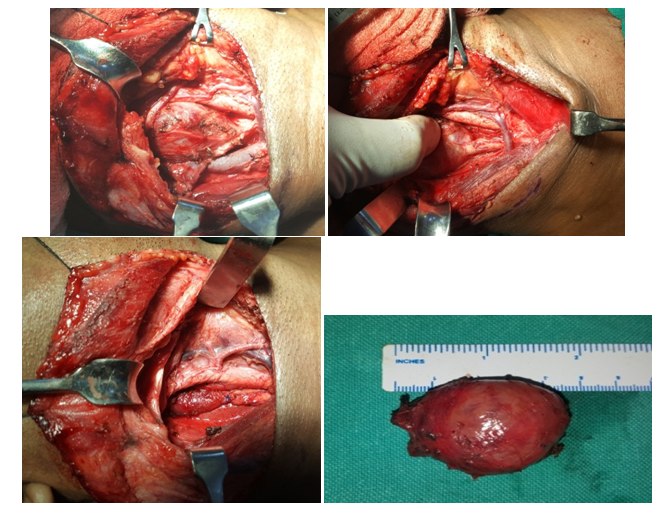

The tumour was found in the carotid sheath between the IJV and the common carotid. It was displacing the IJV laterally and the carotids medially. The vagus nerve was seen going into the tumour while the hypoglossal nerve was found lying adherent to the capsule and was dissected free. The inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve could be indentified and upper part was totally engulfed by the tumour till skull base. The tumour was removed in toto and vagus nerve had to be sacrificed. The cut end of the vagus nerve was sutured to the cervical sympathetic chain hoping that some regeneration may take place in the future though there is no evidence yet available. The HPE of the tumour was consistent with Schwannoma and the IHC was positive for S100 and negative for SMA, Vimentin, Desmin & CD34.

(Figures 6, 7 & 8) The cut end of the vagus nerve sutured with the cervical sympathetic chain and 5cm size of fusiform shaped mass was removed in toto.

Figure 6-8 The tumor is seen displacing the IJV laterally and it is arising from the vagus nerve above the inferior ganglion.

Post op the patient developed hoarseness and (R) vocal cord palsy for which the patient was started on speech therapy. One year follow up had not shown any sign of recurrence and his voice is compensated by the opposite cord.

Schwannomas are rare peripheral nerve tumours; about one third occur in the head and neck region.1 Clinically, they present as asymptomatic slow-growing lateral neck masses that can be palpated along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Pre-operative diagnosis of schwannoma is difficult because many vagal schwannomas do not present with neurological deficits and several differential diagnoses for tumour of the neck may be considered, including paraganglioma, branchial cleft cyst, malignant lymphoma, metastatic cervical lymphadenopathy.2 Furthermore, due to their rarity, these tumours are often not even taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis. When symptoms are present, hoarseness is the most common. Occasionally, a paroxysmal cough may be produced on palpating the mass. This is a clinical sign, unique to vagal schwannoma. Presence of this sign, associated with a mass located along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, should make clinicians suspicious of vagal nerve sheath tumours.3‒5

There is general agreement concerning the great value of MRI in the pre-operative work-up as it is helpful in defining diagnosis and in evaluating the extent and the relationship of the tumour with the jugular vein and the carotid artery. The MRI appearance is considered quite typical and may lead to suspicion of the diagnosis pre-operatively as the cervical vagal neurinoma frequently appears as a well-circumscribed mass lying between the internal jugular vein and the carotid artery. As reported by Furukawa et al.,6 MRI findings are also useful in providing a pre-operative estimation of the nerve of origin of the schwannomas and to differentiate pre-operatively between schwannoma of the vagus nerve and schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain. The vagal schwannomas, in fact, displace the internal jugular vein laterally and the carotid artery medially, whereas schwannomas from the cervical sympathetic chain displace both the carotid artery and jugular vein without separating them.6‒10 Treatment of vagal nerve tumours is complete surgical excision.11 At surgery, these tumours appear as yellowish-white, well-circumscribed masses. Dissection of the tumour from the vagus with preservation of the neural pathway should be the primary aim of surgical treatment for these tumours. Incomplete treatment, such as open biopsy, should be avoided, since it makes definitive excision of the tumour much more difficult. If it is not possible to find an adequate plane and is technically difficult to preserve the integrity of the nerve trunk, the involved segment may be resected and an end-to-end anastomosis performed using microsurgical techniques.

The reported incidence of pre-operative vocal cord paralysis is about 12%, but hoarseness is almost always present following surgery. Therefore, pre-operative assessment of vocal cord mobility should be strongly recommended. Although it is very rare, clinicians should bear in mind the possibility of a nerve sheath tumour in the presence of a neck mass. Pre-operative suspicion is very important, because the patient, and the patient’s family, should be informed about the possible post-operative neurological complications; as far as concerns post-operative vocal cord palsy, an incidence of 85%, has, in fact, been reported. Furthermore, since vagal schwannomas are almost invariably benign in nature, a conservative approach should always be considered in first instance. In the presence of post-operative vocal cord palsy, aggressive voice therapy, for vocal cord compensation, should be started soon after surgery.

None.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2017 Singh, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.