Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Editorial Volume 12 Issue 2

Department of Otolaryngology, Kim ENT Clinic, Republic of Korea

Correspondence: Hee-Young Kim, Department of Otolaryngology, Kim ENT Clinic, 2nd fl. 119, Jangseungbaegi-ro Dongjak-gu, Seoul, 06935, Republic of Korea, Tel +82 02 855 7541

Received: March 06, 2020 | Published: March 10, 2020

Citation: Kim HY. Alternobaric vertigo: eustachian tube function should be assessed before vestibular function. J Otolaryngol ENT Res. 2020;12(2):46-48. DOI: 10.15406/joentr.2020.12.00454

alternobaric vertigo, Eustachian tube catheterization, Eustachian tube dysfunction

ETD, Eustachian tube dysfunction; ABV, alternobaric vertigo

In 1838, Nicolas Deleau, an expert in Eustachian tube catheterization, reported at least one patient who presented with dizziness, tinnitus, and hearing impairment.1 These were later defined as the three symptoms of Menière’s disease.2 Deleau treated the patient by catheterizing the Eustachian tube and administering an air douche, which ameliorated symptoms.1 This early case is a typical example of occlusion of the Eustachian tubes resulting in hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo, and demonstrates why Eustachian tube dysfunction (ETD) should be ruled out before a diagnosis of Meniere’s disease can be made.2 In fact, ETD has long been recognized as a principal cause of hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Therefore, patients exhibiting such symptoms should undergo inflation of the Eustachian tubes as the first step in a thorough clinical investigation.3

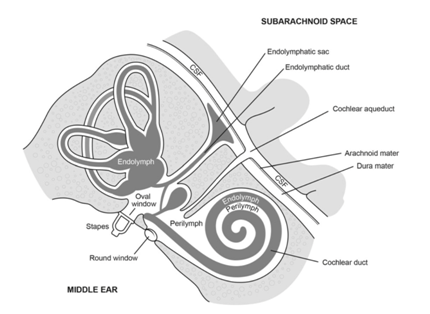

Over a century after Deleau’s first report, in 1942, F.W. Merica3 declared that vertigo caused by obstruction of the Eustachian tubes is a distinct clinical entity. Obstruction of the Eustachian tube disturbs the air pressure which stimulates the perilymph and interferes with normal balance which is maintained by the labyrinthine mechanism (Figure 1). Vertigo associated with ETD is caused in most (and perhaps all) instances by unilateral Eustachian tube obstruction or by more complete obstruction one side than the other. In the literature, most references to ETD-related vertigo are made in general discussion on vertigo due to various causes.3

Figure 1 Demonstration of the communication between cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and perilymph via the cochlear aqueduct. Adapted from “SCUBA Medicine for otolaryngologists: Part Ⅰ. Diving in to SCUBA physiology and injury prevention.” By Mallen JR, Roberts DS. 2019, Laryngoscope, 9999, 3.

Vertigo due to unilateral ETD was first defined as “alternobaric vertigo” (or ‘vertigo altenobarica’), by Dr. Claes Lundgren4 who coined the term in 1965 to describe vertigo in deep-sea drivers.4 It was also used to describe vertigo in aircraft pilots in 1966.5 In both professions, the phenomenon primarily occurs during ascent (and rarely descent) as a result of asymmetrical middle ear pressures (Figure 2).6

Figure 2 Cartoon depicting that alternobaric vertigo can occur in scuba divers and airplane pilots during ascent. Adapted from “Case Report: Persistent Alternobaric Vertigo at Ground Level due to Chronic Toynbee phenomenon.” by Bluestone CD, Swarts JD, Furman JM, et al. 2012, Laryngoscope, 122(4):7.

Alternobaric vertigo (ABV) results from unequal pressure between the middle ears and is usually caused by the pressures changing at different rates7 causing the brain to erroneously perceive the difference as movement. This fundamental mechanism of ABV can be applied to cases of ABV at ground level with asymmetrical middle ear pressures, no matter how minute the difference in pressure is. ABV may be accompanied by a feeling of fullness, tinnitus, and muffled hearing in one or both ears.7,8 In severe cases, nausea, vomiting, and nystagmus can also occur.

ABV should be differentiated from any condition conferring active risk of vertigo or severe disequilibrium. This includes peripheral causes such as Menière’s disease, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, and vertebrogenic dizziness, as well as central disorder.9

In 2012, for the first time, Dr. Charles Bluestone5,6 published a case report documenting a case of persistent alternobaric vertigo at ground level due to chronic Toynbee phenomenon. Bluestone reported that the pathogenesis of otitis media in such individuals may be related to abnormal anatomy causing ETD. In the reported case, vestibular function was abnormal and Eustachian tube function tests revealed dysfunction of the tube. In order to relieve the Toynbee phenomenon, surgery was performed to replace the obstructed ventilation tube with a patent one. Adenoidectomy and bilateral inferior turbinate reduction were performed to relieve chronic nasal obstruction. Postoperatively, the Eustachian tube remained dysfunctional, however vestibular function returned to normal, and vertigo was completely resolved. Bluestone concluded that nasal obstruction and the Toynbee phenomenon may be involved in patients who have vertigo (Figure 3).6

Figure 3 Cartoon showing the pathogenesis of persistent alternobaric vertigo in our patient who had chronic nasal obstruction, the Toynbee Phenomenon, and a unilaterally obstructed tympanostomy tube that created high positive middle-ear pressure. Adapted from “Case Report: Persistent Alternobaric Vertigo at Ground Level due to Chronic Toynbee phenomenon.” by Bluestone CD, Swarts JD, Furman JM, et al. 2012, Laryngoscope, 122(4):8.

One of the most important reasons for assessing Eustachian tube function is the need to make a differential diagnosis in patients with intact tympanic membrane without evidence of otitis media, but with symptoms potentially related to ETD (otalgia, snapping or popping in the ear, fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, or vertigo).5 This strongly indicates that ETD must be ruled out before any vestibular function test.

Vestibular organ dysfunction is caused by poorly regulated pressure in the middle ear. Vestibular organs are considered to be dependent variable organs.10 Every clinical test currently used to assess vestibular function should ideally be performed in a state where pressure in the middle ear cavity is at the perfectly normal value, and perfectly balanced between the two ears.2,11–13

Taking these points into consideration, I would like to call for further case studies and researches into cases of vertigo where Eustachian tube function is assessed before vestibular function is tested. Such investigation may provide exciting insights which impact practice. In addition, publication without consideration of this point, may require revision.

The author has no acknowledgments.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest to disclose.

The author has no funding, financial relationship.

©2020 Kim. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.