Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Case Report Volume 3 Issue 5

1Department of Otolaryngology, Command Hospital, India

2Department of Otolaryngology, Military Hospital Gwalior, India

Correspondence: , Tel +91-7767834137

Received: August 27, 2015 | Published: November 6, 2015

Citation: Galagali JR, Satish K, Abha K, et al. A case of primary aggressive non hodgkin’s lymphoma of parotid gland. J Otolaryngol ENT Res. 2015;3(5):330-333. DOI: 10.15406/joentr.2015.03.00079

Introduction: Primary parotid Non Hodgkin lymphoma is rare and is generally overlooked in differential diagnosis. A high index of suspicion is therefore warranted for the diagnosis. In the present case report, we describe a case of high grade diffuse large B cell Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the parotid gland.

Case presentation: A 24Years old Male presented with a painless mass over the Left parotid region. Imaging studies were suggestive of an infiltrative mass lesion in left parotid along with lytic lesions in vertebral bodies of dorsolumbar spine. The patient underwent total parotidectomy of left Parotid gland with facial nerve preservation. Histopathology of the resected specimen was consistent with primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the parotid gland.

Conclusion: Lymphomas arising from the parotid gland are an uncommon entity, said to account for only 0.6–5% of tumors or tumor-like lesions of the parotid, and are therefore commonly overlooked. This misdiagnosis often leads to unnecessary diagnostic procedures, delaying the initiation of proper treatment.

Keywords: non hodgkin’s lymphoma, parotid gland, diffuse large b cell lymphoma , tumors, parotidectomy, dorsolumbar spine, follicular lymphoma, b-cell lymphoma, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, cervical lymph nodes, erythema, malignant, oral cavity, nasopharynx, larynx , ear, swelling, hypo intense lesion, ultrasonography, preauricular skin incision, submandibular glands, pigmentation

DLBCL, diffuse large b cell lymphoma; MALT, mucosa associated lymphoid tissue; FNAB, fine needle aspiration biopsy; CECT, contrast enhanced computed tomography

Primary lymphomas arising from the parotid gland are uncommon and usually account for only 0.6–5% of tumors or tumor-like lesions of the parotid, and therefore are commonly overlooked. Most cases involve the major salivary glands, primarily the parotid (50-93%) and the submandibular glands.1 The misdiagnosis often leads to unnecessary diagnostic procedures thereby delaying the initiation of appropriate treatment. It is a common knowledge that it is often difficult to make distinction between lymphoma developing primarily in the parotid gland tissue or de novo in the intra-parotid lymph nodes. It has been reported that primary tumours of the parotid gland show no characteristic features on diagnostic imaging, reflecting none of their histological findings.2 The prognosis and morphology, however, is more or less similar between the two origins.3 In our case the main tumour was arising from the parenchyma of the deep lobe of the parotid gland. Most cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma arising in salivary glands are of B-cell lineage including low-grade B-cell lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and follicular lymphomas.4 It is difficult to differentiate between benign conditions from malignant tumours and therefore most patients are subjected to varied surgical procedures before a definitive diagnosis has been made. The head and neck region is the most common site where malignant lymphomas occur, but malignant lymphoma of the parotid gland is relatively rare.5 Generally, surgeons do not anticipate primary Non Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) in the salivary glands pre-operatively and pathologists too find it difficult to give a definitive and diagnostic report based on either frozen section or fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB).6 In contrast to other extra nodal locations of NHL, parotid gland involvement is more likely to be of low grade and the patients have a better prognosis.7 However, in our case it was of high grade. The treatment of primary parotid lymphoma includes chemotherapy and may be radiotherapy. Surgical excision is advocated only as a diagnostic tool.

A 24Yr old male non smoker without any known co-morbidities presented with painless swelling of left parotid region of four months duration which was insidious in onset and gradually progressive. There was no history of any constitutional symptoms, facial nerve involvement and rapid increase in the size of swelling. There was no other significant family or personal history. On examination, the swelling was 5 x 4cm, firm in consistency and fixed to the overlying skin just below the pinna and adherent to upper part of sternomastoid muscle. There was puckering of the overlying skin in the centre with surrounding areas of erythema and dark pigmentary changes. The facial nerve was intact. No other abnormality was found in the oral cavity, nasopharynx, larynx or the ears. There was no palpable enlargement of cervical lymph nodes. Routine biochemical lab tests were within normal limits (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1 Preoperative appearance of the tumour. Note the puckering of overlying skin and the surrounding erythema and hyper pigmentation (arrow).

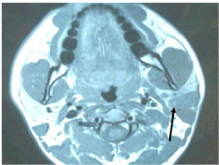

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance image (T1W1 axial) revealing a hypo intense lesion involving the left parotid. There is loss of fat plane with sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Ultrasonography (USG) of the neck revealed a lesion in left parotid with heterogenous echo texture with multiple enlarged lymph nodes at level II and II, largest measuring 1.3 x 1.7 x 2cm at level II on left. Initial FNAC showed pleomorphic adenoma and repeat USG guided Fine needle aspiration, which was repeated twice, showed suboptimal aspirate mixed with blood inadequate for opinion. MRI of the neck revealed multiple well defined lesions in left parotid gland, largest in the superficial lobe and tail of parotid and extending into the deep lobe measuring 32.6 x 20.4 x 22mm and two separate lesions in the deep lobe of the parotid largest being 9.4 x 7.3mm. Also, there were multiple subcentimeter lymp nodes noted at level IIb, III and IV bilaterally. Features suggestive of ‘Multicentric Warthin’s tumour left parotid gland’.

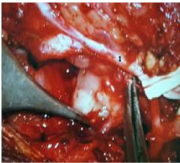

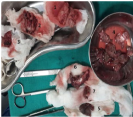

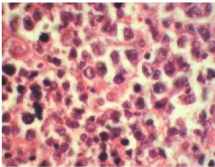

A total parotidectomy with preauricular skin incision was planned. However, intra-operatively involvement of surrounding muscles, periparotid lymph nodes and level II b / III lymph nodes was noted. Facial nerve and its terminal branches were preserved with careful dissection, however there was adherence of inferior division of facial nerve to the tumour mass which was cleared carefully under microscopic control. The retromandibular vein was ligated and a globular mass seen arising from the deep lobe of the parotid. The tumour was removed in to along with other smaller mass from the deep lobe. Total parotidectomy was performed along with excision of unhealthy overlying skin, part of upper and anterior border of Sternocleidomastoid muscle and a part of posterior belly of Digastric muscle. Level II b and III lymph node clearance was done. A suction drain was put for 48hours. Post operative recovery was uneventful with minimal deviation of angle of the mouth which recovered fully after two weeks. Histopathology of the mass revealed diffuse large B cell NHL showing sheets and strands of atypical lymphoid cells with involvement of superficial, deep lobe of parotid, Sternocleidomastoid muscle and Digastric muscle. Skin and level IIb and III lymph nodes also revealed similar population of atypical cells with perinodal extension. The tumour cells were positive strongly for CD20, LCA and CD79a on Immunohistochemistry (IHC). However, the cells were negative for CD5, CD3, EMA, CK and TdT on IHC. The Ki-67 labelling index was 100% (Figures 3-8).

Figure 3 Facial Nerve was identified and secured with careful dissection. Deep lobe tumour can be seen inferior to the lower division of facial nerve (arrow).

Figure 4 Intraoperative image showing: Deep lobe tumor of parotid being delivered1, sternomastoid muscle2, facial nerve3 and Spinal accessory nerve4.

Figure 5 Under microscopic control the adherent lower division of facial nerve1 was freed from the deep lobe tumour.

Figure 6 Resected specimen: Superficial lobe of parotid1, deep lobe of parotid2, parotid tumour mass3, lymph nodes4, skin5, part of SCM6 and post belly of digastrics muscle7.

Figure 7 HPE Specimen (H&E, x200) - Infiltration of salivary gland parenchyma with atypical lymphoid cells having high N: C ration and moderate degree of nuclear pleomorphism.

Figure 8 Postoperative image after removal of deep lobe and superficial lobe of parotid showing accessory parotid remnant1, sternomastoid muscle2, internal jugular vein3, retromandibular vein4, spinal accessory nerve5 and facial nerve6.

The patient complained of low back ache in the workup period for which a dorso-lumbar spine X-Ray was obtained which was normal. A Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) chest and abdomen was advised keeping a high index of suspicion in view of a high grade DLBCL. The CECT revealed multiple ill defined lytic lesions noted in the bodies of C7, DV4-DV6, DV10, DV12, LV2, SV1 and bilateral iliac bones. Also, a compression fracture of DV4 was noted. Rest of the metastatic workup including the bone marrow study was normal. With the clinical stage IV disease, patient was started on RCHOP chemotherapy regimen. As part of the RCHOP regimen the patient received eight cycles of Inj Rituximab (375mg/m2), Inj Cyclophosphamide (750mg/m2), Inj Doxorubicin (50mg/m2), Inj Vincristine (1.4mg/m2) and Tab Prednisolone 40mg/m2/day for 5days. The chemotherapy was well tolerated. Presently, the patient is disease free after one year and is on regular follow up (Figures 9 & 10).

Most of the extra nodal lymphomas of the head and neck are NHL and in 4%-5% of cases the parotid gland is involved.8,9 Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the parotid gland may be classified as extranodal if the origin is from the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) or nodal if the true origin is from lymph node within the gland. The lesions, in the opinion of few authors, arise from the intra-parotid lymph nodes associated within the gland and involving the gland parenchyma secondarily. The theory makes it difficult to establish the true origin of the disease.10 Although considered insufficient by some authors.11 Hyman & Wolff12 have suggested some criteria to consider a lesion as primary parotid gland lymphoma:

Parotid lymphoma most commonly presents as a painless mass indistinguishable from other non-malignant or other more common epithelial tumors. This explains why this diagnosis is commonly overlooked and patients are often subjected to unnecessary procedures and a delay in diagnosis. In most cases the facial nerve is not jeopardized.13 Diagnosing parotid lymphoma can be a difficult task, as evidenced by the unnecessary tests conducted before correct diagnosis is made.13 One should suspect it when the radiological picture is not matching with the FNAC findings. One should keep in mind that high grade NHL can involve the skin and underlying muscles. Also high grade NHL can metastasize in spine so such patients if they complaint of backache then a CT scan of spine is warranted as an X-ray may miss the lesions. Most salivary gland non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas tend to remain localized and relapse locally. Therapeutically, complete tumor resection with the addition of chemotherapy. Recently, the use of rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody has emerged as treatment option in patients with B-cell lymphomas.13,14

This case has been described to highlight the relatively rare presentation of primary NHL of the parotid gland. This difficulty in pre and intra-operative diagnosis often results in unnecessary radical operations to the patient with all its associated risks involved. Also, attention is drawn towards the warranted metastatic workup keeping a high index of suspicion in a case of high grade DLCBCL of the parotid gland.

None.

Author declareas there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2015 Galagali, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.