Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Despite the fact that disabling, age related hearing loss or presbycusis affects around 360million people globally World Health Organisation, there is quite often a lengthy delay between the time an individual first notices that they are having hearing difficulties and when they actually seek help from a hearing professional.1 So why is it that people take so long to accept that their hearing is impaired and investigate the potential solutions? The purpose of this paper is to discover, by means of a literature review, some of the barriers that an individual may encounter during the journey of ‘ownership’ of their hearing loss, and to determine how, once the decision has been made to address their hearing problems, the interaction between client and professional can facilitate or impede solution finding.

Keywords: delay, help-seeking, hearing loss, stigma

Despite the fact that disabling, age related hearing loss or presbycusis affects around 360million people globally World Health Organisation, there is quite often a lengthy delay between the time an individual first notices that they are having hearing difficulties and when they actually seek help from a hearing professional.1 So why is it that people take so long to accept that their hearing is impaired and investigate the potential solutions? Untreated age-related hearing loss can lead to negative consequences such as social isolation, depression, anxiety, loneliness and stress in relationships or at work. There have even been some suggestions that a delay in treating age related hearing loss may result in early onset dementia.2 We know that there is an argument to suggest that cost and expense play a major part in this delay but even in the UK, with the availability of free hearing-aids on the NHS, only 38% of adults with a treatable hearing loss are in possession of hearing-aids (Action on Hearing loss, 2011). Therefore, there must be additional factors that influence help-seeking for hearing impaired older adults.

The purpose of this paper is to discover, by means of a literature review, some of the barriers that an individual may encounter during the journey of ‘ownership’ of their hearing loss, and to determine how, once the decision has been made to address their hearing problems, the interaction between client and professional can facilitate or impede solution finding.

The main source for papers for this review was via the Shibboleth/Athens search engine, utilising key words; ‘delay’, ‘help-seeking’, ‘hearing loss’, ‘stigma’. A selection of peer reviewed articles were selected that focused on factors affecting help-seeking, stigma of hearing loss and hearing solution adoption.

When an individual is confronted with a potentially stigmatizing situation, they appraise that trait as a threat to their social identity.3 Because of this, an individual will start to compensate by developing ‘self-protection’ techniques and may try to ‘play down’ or ‘deny’ the stigma. In addition, people who present with age related hearing loss are often perceived by others to be socially inept with diminished cognitive ability, making them uninteresting and poor communication partners.4 A recent study that supports this was by Southall, Gagne and Jennings titled–“Stigma: A negative and a positive influence on help-seeking for adults with acquired hearing loss”, aimed to gain a better understanding of how stigma impacted upon the help seeking activities of adults with an acquired hearing loss. The study was conducted using audio-recorded, semi structured interviews with 10 members of a peer support group who had a hearing loss, to gain a two sided perspective on possessing a stigmatizing attribute. This ‘two-sided’ perspective would give them an insight into the thoughts and feelings encountered by an individual with a stigmatising attribute pre and post help-seeking. The study suggested that individuals with a hearing impairment experienced a climax of negative stress leading to an unmanageable situation due to stigma. Part of this stress was caused by ‘denial’; they did not want to be ‘hard of hearing’ due to the stigma. It was easier to conceal their hearing loss from friends and family for fear of being labelled ‘old’ or ‘stupid’. This is also supported by a study undertaken by Wallhagen,5 who established that hearing aid/loss stigma was associated with experiences of altered self-perception, e.g. able vs disabled; smart vs cognitively impaired, and that these experiences often delayed the decision to seek help regarding a solution.5

Mounting losses also contributed to a climax in negative stress, particularly in social and work situations.3 Participants expressed feelings of anger and resentment towards family and friends as they felt these relationships had changed for the worse – constantly having to repeat themselves in social situations and knowing that this was causing frustration for both parties. Mounting losses, also contribute to uncomfortable situations in the workplace, with participants stating that they feared negative actions such as demotion, termination or being asked to give up work-related duties due their hearing difficulties, almost as if they were ready for ’retirement’. This is supported by the MarkeTrak VIII survey6 which surveyed 3174 hearing aid owners and 4345 non-hearing aid owners, with a hearing impairment. The survey suggested that those who were in a possession of a hearing-aid were less likely to be ‘employed’ than those that did not own a hearing aid, with ‘retired’ being the employment status defined by those in possession of a hearing instrument.

Another aspect to be taken into consideration is the stigma of the very look and feel of the hearing aid itself causing an individual to delay in help seeking. For many years, hearing-aids have caused a reaction of distaste and displeasure regarding cosmetics and vanity. In recent years, manufacturers have exacerbated this reaction by continuing to strive for smaller, more cosmetic solutions and therefore re-enforcing the stigma of the visibility of a hearing aid. This is outlined in a study by Laplante-Levesque, Hickson and Worrall–‘Factors influencing rehabilitation decisions of adults with acquired hearing impairment’. In this study, 22 participants with acquired hearing impairment were given four different solutions to their hearing difficulties. The options offered were hearing aids, group communication program, individual communication program and no intervention. The stigma relating to the use of hearing aids was a prominent feature of the interviews conducted with the participants who chose not to have hearing aids as an intervention. “If you put hearing aids in your ears, this is pride, it’s an admission that you’re getting old”.7

The participants saw a direct correlation with wearing hearing aids and aging, with the visibility of the hearing instrument meaning that they would have to disclose their hearing difficulties. However, in the study conducted by Wallhagen5–‘The Stigma of Hearing loss’, it is not this ‘disclosure’ that is suggested as a barrier to help-seeking, but the emphasized marketing of the cosmetics of new hearing aids feeding the ‘vanity’ issue by hearing aid manufacturers.5

Overall, there is convincing evidence to suggest that the stigma of hearing loss and the wearing of hearing aids has a fundamental effect on ownership of and the decision making process of whether to seek help or not. Whilst there may be some differences in the motivation for this apparent delay in help-seeking by the papers reviewed on this subject, there is significant support to suggest that stigma is still the salient reason given for choosing to delay in seeking a solution.

Environmental factors

When it comes to an individual seeking help to address an acquired hearing loss, the decision to delay can be reinforced by external social factors, or environmental influences. There is some evidence to suggest that ‘stereotypes’ are formed which may deter many people from seeking help for their audiological needs.3 Individuals will feel the need to play down or disconfirm a stereotype and make favourable comparisons of their own situation to other who may appear to be in a much more difficult situation.

People with acquired hearing loss fear any association with a negative stereotype and therefore this can serve as a social barrier to rehabilitation.3 In the study by Southall, Gagne and Jennings previously described, the lack of understanding by the general public, family and friends of the challenges faced when an individual has an acquired hearing loss, contributes to the denial and the delay in help seeking. The study suggests that regular interaction socially with family and friends that are unable to relate to these challenges acted as a barrier to help seeking. It is easier to relate to someone with sight impairment – just close your eyes and immediately your vision is restricted – this is not as easy when trying to simulate a hearing loss, therefore it is more difficult to demonstrate empathy or understanding. “There is something noble about being blind and coping. Hearing impaired? What are you whining about?”.3

Other people’s experiences with hearing aids can also influence when an individual seeks help. A study conducted by Mahoney et al.,8 suggests that an individual’s decision to seek help for their hearing problems is strongly influenced by the attitude of their family, friends and doctor. The study of 95 clients with hearing impairment strongly suggests that these three afore mentioned influences were the reason for deciding to find a solution. However, the majority of these responses were from individuals that had retired and were no longer in employment, with those that still worked citing colleagues, lawyers and employers as the most influential, further supporting the suggestion that work based mounting losses as previously discussed may facilitate help seeking.8

The decision to seek help regarding hearing difficulties is also determined by the perceived benefit of wearing a hearing aid. An individual’s decision to adopt a hearing aid as a solution was influenced by their perceived disadvantages–for example, not having a significant effect on background noise, or that they are fiddly and uncomfortable.9 The MarkeTrak VII survey reported that two-thirds of no-hearing aid adopters perceived these disadvantages.6 In agreement with this theory is van den Brink et al.,10 who reports that hearing aid users stated that they appreciated the significant benefits of amplification over non-users.10

Overall, there is significant evidence to suggest that the attitudes and opinions of others affect the decision making process regarding help seeking. The literature suggests that external environmental and social factors can be a major deterrent when seeking a solution for hearing loss, particularly when the only solution is amplification as these negative attitudes reinforce the stigma surrounding them. Educating the general public and those with a hearing impairment on the challenges faced with a hearing loss may start to erode some of these negative attitudes and facilitate empathy.

Psychological factors

There are a number of psychological factors which may influence when and why an individual decides to seek help from either their doctor or a hearing professional. Several papers discuss the ‘perceived disability’ and how that can influence the decision to seek an audiological consult.9 Those affected by hearing loss tend to accept that experiencing hearing difficulties is a part of the ageing process and therefore do not need to consult with an audiology professional. It is only when an individual perceives that the severity of their loss has increased or worsened that this consult is sought. The psychosocial effects of presbycusis are variable, and therefore adaptation to tiny changes in diminished high frequency loss are more prevalent than recognition of the problem.1 Those affected by presbycusis may tend to adopt coping strategies. One such strategy is the communication of their difficulties to their significant others, who, in 50% of cases, advised that they seek help.11 A study by Carson,1 of 7 women (restricted to women to avoid the potential confounds of gender and noise-induced hearing loss] that were all seeking help for uncomplicated presbycusis, noted that the women undertook a form of ‘self-assessment’ known as ‘contrasting/comparing’. This was the process of comparing the slow decrease in hearing ability to that of losing one’s sight, or contracting a potentially life threatening illness. When ‘comparing’ is utilised in this way in relation to hearing loss (presbycusis), the severity of the loss is judged in relation to that comparison or the comparison to someone else’s hearing ability. In addition, ‘contrasting’ is adopted by means of assessing how they used to hear, contrasting their hearing ability now to how they heard at different points in time. The study suggests that contrasting/comparing is a way of putting hearing difficulties into context when it comes to help-seeking. Following this self-assessment, hearing impaired individuals adopt a ‘cost vs. benefit’ theme. This means that the individual will assess the relationship between the cost of the action and the value of the resulting benefit.1

Psychologically, those individuals with an acquired hearing loss are less likely to adopt hearing aids if they allow others to dominate their decision making. Research suggest that hearing-aid seekers have unique personality traits that allows them to have more personal control over the decision making process.9 A study by Cox supports this theory, suggesting that hearing aid users display traits such as low levels of neuroticism and high levels of agreeableness,12 and suggesting that hearing aid seekers are more pragmatic and conventional. However, a conflicting study by Humes did not show a significant difference between hearing aid users and non-users.9

There is also a suggestion in related articles, that an overwhelming fear of technology can have an adverse effect on when a person seeks help. Hearing aids are, in fact, small devices that contain intricate and perishable technology, which can deter some individuals from their adoption. In a study conducted by Gonsalves & Pichora-Fuller13 of 135 adults of 65years and older to determine the uptake of hearing aids, results showed that the majority of the participants with hearing loss who did not use hearing aids, also used the internet and other technologies less than the participants who did.13 As discussed in Meyer & Hickson 9, these results could be taken as that the fear of technology is influencing the decision to adopt hearing aids as a solution to hearing loss, however, there could also be other factors that could affect the result between the two group, such as other health issues, vision impairment, etc.9 In modern audiological consultations, end users can often be described as ‘silver surfers’, who are familiar with the internet and quite often present themselves in clinic referring to e-mails and texts received on smart phones and other devices. Therefore, an assumption cannot be made as to the influence of technology on seeking a solution to hearing impairment.

Overall, the impact of psychological factors on seeking help cannot be underestimated. The emotional and psychological stress of coming to terms with a hearing loss is critical when taking into account the triggers for accessing audiological consultation. These ’critical junctures’ as described in Southall et al.,3 caused most of the study subjects to seek help during a time when negative stress and positive energy were out of balance - critical juncture 1, and encouraged their involvement in peer support groups during times where positive energy far outweighed negative stress – critical juncture 2.3 Evidence suggests that there is a need to experience these emotional, psychological factors to facilitate the help-seeking behaviours required.

Physiological factors

The notion that hearing loss is just a part of aging and requires no attention and assistance appears to be a typical opinion of the older adult.14 When looking at the typical presentation of age-related hearing loss, literature suggests that the earlier the age of onset, for example prior to retirement age, the more likely an individual is to seek help for their hearing difficulties.15 Should the individual be no longer in employment, then the delay in seeking help is increased as this is almost an admission of ‘getting old’. However, there is evidence to suggest that should the hearing difficulties be more complicated in nature, such as an increased awareness of hearing sensitivity or asymmetry, then it is possible that a solution may be sought sooner.14

Gender has also been associated with the potential to delay when seeking help or advice for any illness, not just acquired hearing loss. Southall et al.,3 suggest that the approach one takes to help-seeking may be influenced by gender, which is supported by a study conducted by Erler & Garstecki,16 which focused on women perceptions on hearing loss. The suggestion here is that hearing-aid adoption and ownership of hearing difficulties is less daunting for women of retirement age. Contrary to this opinion, in a literary review by Saunders et al.,14 there is little to no evidence to suggest that gender, personal confidence or attributes influence help seeking behaviour, but that it is a combination of factors irrelevant of gender that ultimately prompts the step towards rehabilitation.

Almost linked with the fear of technology discussed under psychological factors, is the association of lack of dexterity with hearing aid uptake. Literature states that older adults have poorer finger dexterity possible due to such ailments as arthritis.9 Hearing aids are becoming increasingly smaller to address the stigma of visibility, and therefore require a certain amount of competent, manual dexterity to handle and insert the instruments correctly and to ensure that they are correctly cleaned and maintained. In the MarkeTrak VII study, Kochkin.6 showed results that demonstrated that poor vision or manual dexterity were a significant reason for no uptake of hearing aids –19% of 1031 subjects.6 Literature suggests that the fear of being able to ‘handle’ the hearing aids correctly and without damaging them, leads to the decision not to address the hearing difficulties being experienced. But in direct contrast to this, there is evidence to suggest that finger dexterity plays little part in the decision making process.9

From the literature reviewed, it appears that physiological factors may influence the decision to seek help or not, especially when taking into consideration the evidence surrounding age of onset and the stigma of ‘getting old’. However, there is little evidence to suggest that gender is a major factor, though the lack of ownership from older adult males could be seen as support for the gender argument, but more research is needed to understand if this is relevant or ‘historical interpretation’

It may seem that including the patient/clinician relationship as a barrier to help-seeking is a little like shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted, but there is evidence to suggest that an individual who has overcome the barriers discussed in this review, may be catapulted back into the cycle of denial following a poor initial consultation with an audiologist or hearing professional.

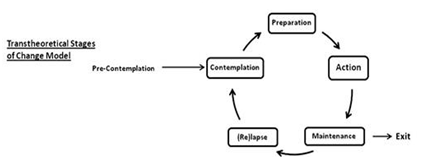

Because of the emotional reactions to a diagnosis of being hearing impaired, individuals often raise these emotional, psychosocial concerns during their audiology consultation. Figure 1 the Trans theoretical Stages of Change Model, shows the emotional and psychosocial thought processes experienced during the consideration of help-seeking. This process of contemplation and action can be exited at any time, such as in a poor consultation lacking in empathy by the conducting clinician, causing the patient to re-enter the ‘contemplation’ stage again, further encountering the barriers they had previously overcome.

Figure 1 Transtheoretical Stages of Change Model.14

A study by Ekberg et al.,17 of 63 video-recorded initial audiology consultations, aimed to demonstrate the importance of the empathic first consultation with the audiologist or hearing professional. The study focused on when and how patients present concerns about hearing aids and in turn, how these concerns are addressed by the audiologists. In 51%of the appointments, the subjects raised concerns that were emotional and psychosocial in nature, displaying a negative stance on the possibility of adopting hearing aids. It was observed that the audiologists did not respond to this ‘negative stance’ but were more focused on progressing the discussion regarding the purchase of hearing aids.17 When patients experience a consultation that fails to address their very genuine concerns, or to pre-handle their potential objections to adopting a hearing solution, these concerns, however trivial they may seem to the audiologist, remain invalidated and continue to trigger the ‘relapse’ element of the change cycle. When this happens, the risk of the patient leaving the consultation room without having made a positive decision regarding their rehabilitation is increased. Though it may be an uncomfortable move to make, it is suggested that further questioning by the audiologist regarding the patient’s feelings and concerns, may illicit a more positive outcome.17 This is supported by Laplante-Lévesque et al.,7 stating that both the patient and the clinician should participate in the information exchange and decision making, with the clinician eliciting the clients prior knowledge, fears and objections to a hearing solution.7 This study concluded that when an individual is engaged in the consultation by the clinician, focusing on ‘shared’ decision making, the adults with a hearing impairment were more likely to adopt and adhere to an intervention, such as hearing aids, than if the decision had been made for them. As previously discussed, a rush to provide a solution following a diagnosis does not give the patient time to absorb the fact that they have a hearing impairment and therefore may hinder their rehabilitation. The decision to address hearing difficulties by an individual may seem practically sound, but this decision has usually been driven by emotion; not being able to hear their grandchildren, or feeling isolated in social events. Ekberg et al.,17 suggest in their study that emotionally focused communication is fundamental to patient –centred care and that this response by the clinician to the psychosocial needs facilitates trust, without which rehabilitation may be lengthy or not chosen at all. Emotionally focused communication is thus a critical aspect in the delivery of healthcare as a whole and may need greater emphasis within audiology.17

Not addressing patient’s emotional, psychosocial concerns also has an impact on the efficiency of audiology appointments. Audiologists are becoming increasingly pressured within their daily clinics to complete a full assessment and recommend a solution within a strict time frame. This may suggest a reason for the lack of emotional communication within audiology appointments, as the clinician is focused on the time rather than the needs of their patient. Ekberg et al, suggest that this contributes to the patient-clinician interaction becoming increasingly extended as the client persists in re-raising their concerns. Taking time to understand and empathically respond to patients concerns may make the audiological process more efficient as well as increase compliance.17

From the evidence, it is hard to disagree that addressing the psychosocial needs is fundamental to a positive outcome regarding solution and rehabilitation. It may have taken an individual many years to make the decision to seek help, and if the clinician is too focused on diagnosis and prescribing rather than pre-handling the potential objections or barriers, then the risk is that no solution will be adopted. This is supported in the study by Ekberg et al, who noted that in the appointments where patient’s concerns were left unaddressed, then the appointment ended without the patient agreeing to hearing aids. In the cases where the hearing aids were available free of charge or state funded, they were taken, but their commitment to wearing them was equivocal.17 There appears to be some correlation between client - clinician relationships and the successful adoption of a rehabilitation solution.

In summary, the literature reviewed has highlighted there are a number of factors that influence when an individual seeks help for their hearing difficulties. This review has also demonstrated that once the decision has been made to seek help, then the calibre of the consultation received may greatly determine whether a solution is adopted, or if the cycle of fear and denial is re-entered. However, the literature reviewed focused on one or two potential factors in isolation, whereas this review has outlined there are multiple factors that contribute to a delay in help seeking and that they do not tend to occur in isolation, but manifest themselves at different stages along the journey of ownership of hearing loss. One should also take into consideration that the number of participants in the studies reviewed were not abundant (apart from the MarkeTrak study), and therefore may not give a true and fair representation of the emotional, physiological or psychological fears that present to an individual with hearing impairment. This review has noted however, that the stigma associated with hearing loss is still extremely prevalent and that this fear of being seen as ‘old’, ‘stupid’ or even ‘unemployable’ bears greatly on any decision to seek consult. It was interesting to note that, although some studies stated that cosmetics and visibility of hearing aids was still there as a concern, it was more that if the hearing aids were ‘seen’ then it would facilitate an ‘admission’ of their hearing loss , which supports the emotional and psychosocial barriers to help-seeking.

The most interesting finding was the effect a poor audiological consultation can have on the cycle to accept change and seek a solution. It would appear that the audiologist should not just see themselves as the ‘prescriber’ but as the ‘counsellor’ and ‘rehabilitator’. Too early a focus on suggesting hearing aids, rather than discussing the environmental, psychological, physiological and emotional barriers that have been overcome to arrive in the consultation room, may potentially result in the whole cycle being revisited - further validating the individuals original fears and concerns.

It is clear from the literature reviewed that hearing impairment is still extremely emotional and upsetting to older adults. Leaving hearing loss unaddressed may lead to other adverse effects on health and wellbeing so for this reason alone, further investigation and research is required to understand which of the barriers and factors discussed in this review are pivotal when considering the motivation to seek audiological consult or to adopt hearing aids.

I would like to thank Phil Gomersall, MSc (Audiology), for his guidance and support whilst researching and completing this literature review.

Author declareas there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.