Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Mucor is a saprophytic fungus. Although it commonly invades the nose and the paranasal sinuses, cutaneous, pulmonary or gastrointestinal lesions may also be seen and haematogenous spread to other sites can also occur. The predisposing factors include Diabetes Mellitus and other conditions causing immunocompromised state. However, rare cases without any underlying disorder have been also reported. This case is described to demonstrate rarer neurological presentation of Oto-cerebral Mucormycosis rather than the well recognized rhino-orbito-cerebral form. Early diagnosis and institution of treatment is the mainstay to successful therapy.

Keywords: mucormycosis, canal wall down mastoidectomy, amphotericin b, diabetic

CVST, central venous sinus thrombosis; ICA, internal carotid artery; GMS, gomori methamine silver; ZN, ziehl-neelsen; AFB, acid fast bacilli; KOH, potassium hydroxide; PAS, periodic acid-schiff staining

Mucormycosis is the common name given to clinical disease caused by fungi of the order Mucoraceae of class zygomycetes. Mucormycosis is a life threatening fungal infection which commonly affects the Immunocompromised hosts almost uniformly in developing as well as industrialised countries. Mucorales are distributed into six families all of which can cause cutaneous and deep fungal infections. Out of the six families Rhizopus oryzae is the commonest cause of infection. Among the other species that are isolated include Rhizopus microsporus var. rhizopodiformis, Absidia corymbifera, Apophysomyces elegans, Mucor species, and Rhizomucor.1 Mucormycosis is seen more commonly in the nose and paranasal sinuses, whereas candida and aspergillus fungal infection, which are rather commoner,2,3 are seen in the external auditory canal. The invasive variant of mucormycosis is commonly seen in diabetic patients. Mucormycosis involving the middle ear is a rare clinical entity. Probable portal of entry to the middle ear is either from nasopharynx through Eustachian tube or through the already existing perforated tympanic membrane.4 The rarity of involvement of the middle ear makes it difficult for the clinician to suspect the same as the principal diagnosis. Clinical presentation may be similar to Chronic Otitis Media with probably the chief complaint of predominant ear pain with referral to the mastoid and upper neck. Further complication of Mucormycosis of the middle ear involvement in terms of intracranial extension with brain and venous sinuses involvement further complicates the presentation adding to the diagnostic dilemma. Early diagnosis is the mainstay of successful therapy which involves surgical debridement and administration of antifungals like Amphotericin B.4,5

A 55yrs old Hypertensive and Diabetic male patient brought to the emergency department with history of right hemiparesis and slurring of speech. He also had history of foul smelling mucopurulent otorrhea left ear and otalgia left ear radiating to left hemicranium and upper neck of three months duration. Patient also developed deviation of angle of mouth to right a month before the hospitalization.

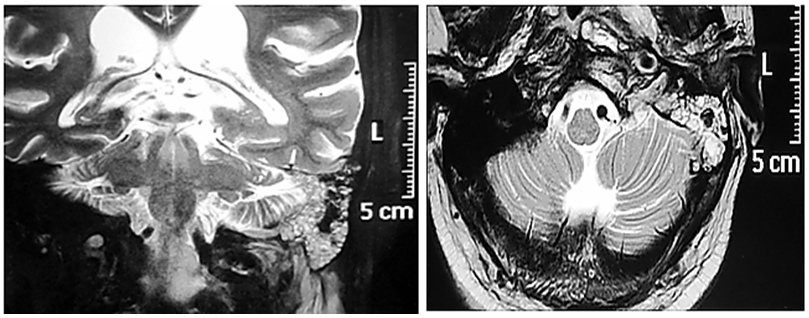

Thorough clinical examination revealed right hemiparesis, left Lateral rectus palsy suggestive of sixth cranial nerve palsy and deviation of angle of the mouth due to left Facial nerve Palsy (Lower Motor Neuron type) (Figure1). There was a palpable firm mass in the upper neck behind the angle of jaw on left side, post auricular lymphadenopathy and a positive Griesinger’s sign (Figure 2). Otoscopy revealed active mucopurulent discharge with granulations and necrotic tissue in external auditory canal and the middle ear (Figure 3). Magnetic resonance imaging and Contrast enhanced computed tomography temporal bones and neck revealed left coalescent mastoiditis with extension across the subperiostium with fluid collection involving the soft tissue of left postauricular region, extradural abscess from left petrous, basal meningitis and pontine infarct. Magnetic resonance venogram and angiogram revealed Central venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) of left sigmoid sinus, transverse and superior sagittal sinus, loss of luminal signal of left internal jugular vein at jugular bulb and decreased flow related to enhancement involving the petrous segment of the left internal carotid artery (ICA) (Figure 4).

Figure 1 Preoperative picture of the patient showing Cranial nerve VI and VII palsy (on the patient´s left side of the face).

Figure 2 Griesinger sign and Bezold abscess: Intra-operative picture of the patient showing swelling at the retro auricular region of the left pinna and the left side of the neck along the anterior border of sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Figure 3 Otoendoscopic picture of the left Ear showing necrotic material and granulations in the external auditory canal and the middle ear.

Figure 4 MRI revealing the lesion extending from the mastoid into the brain up to the cerebellopontine angle and upper neck on left side.

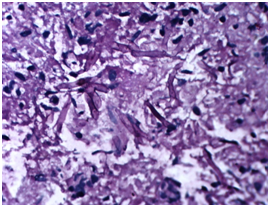

Patient was started on Amphotericin B after a test dose and a cumulative dose of 3grams was reached. A surgical intervention in terms of Tympanomastoidectomy with neck exploration was planned to decrease the disease load. However an extensive surgery was not possible because of poor surgical risk owing to multiple co-morbidities of uncontrolled hyperglycaemia, hypertension and deranged renal function tests. A canal wall down Mastoidectomy was done with exenteration of all the mastoid air cells including perisinus, perifacial, peri-labyrinthine and tip cells. The jugular fossa was cleared. Thick inspissated pus was evacuated from the mastoid cells. The postaural incision was extended on to the neck. Thick yellowish necrotic tissue involving upper part of sternocleidomastoid and posterior belly of Digastric muscle was seen Figure 5. The yellowish necrotic tissue was removed en block including the upper part of Sternocleidomastoid muscle reaching upto the stylomastoid foramen. Debridement was done and tissue taken for biopsy. Gomori Methamine Silver (GMS) staining of the biopsy material revealed fungal hyphae favouring Mucor species. Repeated cultures, Gram stain and Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain for Acid fast bacilli (AFB) were negative (Figure 6).

Figure 5 Showing the picture of thick inspissated pus and yellowish necrotic material in the neck in relation to the sternocleidomastoid muscle after its retraction and the posterior belly of digastric muscle indicating the possible breakout of the mastoid infection through the mastoid tip.

Figure 6 Histopathological specimen showing septate acutely branching fungal hyphae suggestive of Mucor.

Conservative measures in terms of control of blood sugar, hydration, nutrition and monitoring of renal function tests continued throughout. Post operative period was uneventful and the patient improved remarkably over a period of few days with a well healed postaural scar (Figure 7).

Mucorales are saprophytes found in the soil and decaying organic matter. Mucormycosis of the Temporal bone is rare clinical entity with only a few cases been reported.4,5 Mucormycosis is an aggressive, opportunistic fungal infection commonly involving the rhinocerebral site causing sinonasal, orbital or deep facial infection. It is commonly seen in Immunocompromised hosts for example Diabetics in ketoacidosis typically develop rhino-orbito-cerebral disease than the less common pulmonary and disseminated form.6‒8 However, cases in patients without any comorbidity have been reported. There are six major forms of this which include rhinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, disseminated, gastrointestinal and miscellaneous. The most common form of mucormycosis is rhinoorbitocerebral, followed by cutaneous and pulmonary. The spread is via the lymphatic system, vessels and nerves. Pathologically, patients in acidosis have increased load of iron owing to dissociation from the sequestering proteins. Also, hyperglycemia and acidosis negatively impact neutrophil chemotactic activity and phagocytosis. However, neither of the two mechanisms describes preferential rhinocerebral involvement in the diabetic patient in ketoacidosis than the other forms of mucormycosis. Involvement of the blood vessels leads to infarction, hemorrhage and thrombosis. The invasive Mucormycosis is characterized by vascular invasion causing haemorrhage, thrombosis and necrosis of tissue.9 The Temporal bone involvement in Mucormycosis is very rare and may resemble a refractory Otitis externa. McGill previously described Mucormycosis of the Temporal bone.10 Mucormycosis of the temporal bone may involve the middle ear cavity without necrosis or it may involve even the inner ear with extensive necrosis.11 It may involve the skull base or the intracranial compartment presenting with Cranial nerve deficits and other neurological symptoms.

Intracranial fungal infection can be caused by the extension of a localized nasal or paranasal sinus infections, cavernous sinus invasion, or direct infection of the brain parenchyma. Infection can invade adjacent blood vessels, including the retinal artery, ophthalmic artery and internal carotid artery, causing complications such as intracranial infection, systemic embolism, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral infarction. Very rare cases have shown ICA occlusion and secondary abscess formation.12,13 Cranial nerve involvement indicates a severe infection and a bad prognosis. Yun et al.14 first reported a case of middle ear Mucormycosis with facial palsy in a diabetic patient.

Complications of relatively rare Mucormycosis in terms of intracranial involvement with cranial nerve involvement adds to the diagnostic difficulty and delay in institution of treatment.

Diagnosis of Mucormycosis necessitates a high index of suspicion, as almost half of the cases are identified in post mortem studies.15,16 Diagnosis can be made by imaging studies and histopathological examination of the infected material. The fungus forms fluffy white, gray, or brownish colonies on Sabouraud dextrose agar within 1-7days. Direct microscopic examination can be done with 20% potassium hydroxide (KOH), Gomori's methenamine silver staining, hematoxilin and eosin staining, or periodic acid-Schiff staining (PAS). They are classically described as broad ribbon-like aseptate hyphae with right-angled branching. However, they are pauciseptate and the angle of branching can vary from 45° to 90°. Angioinvasion and tissue invasion are typical of this infection.

Our case was complicated by the presence of various comorbidities, and complication of the Mucormycosis of the temporal bone involving the intracranial cavity and the neck spaces. The diagnosis was clinched by the imaging studies and a positive histopathological finding.

Successful treatment of invasive mucormycosis necessitates prompt and early diagnosis, control of risk factors, surgical debridement of necrosed tissue and antifungal drugs. Amphotericin B is the antifungal of choice for the treatment of mucormycosis. Nephotoxicity, however, is a limiting adverse side effect of amphoterecin B. In our case, the patient developed deranged renal function tests during the course of treatment with Amphotericin B.

Various studies have explained the favourable role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on presumption that increased the oxygenation of the affected tissues improves the ability of the neutrophils to kill the organisms.17 Also, high oxygen inhibits the germination of fungal spores and growth of mycelia in vitro.

This case has been described to highlight the relatively rare presentation of Mucormycosis involving the Temporal bone and presenting with complex symptomatology including weakness left side of the body, slurred speech, diplopia, facial palsy, ear discharge and otalgia. Otocerebro mucor may involve cerebral venous sinuses and internal carotid artery in its course through cavernous sinus and can lead to intraluminal thrombosis locally and cerebral infarcts. It can also spread to involve the cranial nerves at cavernous sinus or at ear and it can trickle to involve the deep neck spaces. A prompt diagnosis, control of predisposing factors, early surgical debridement of infective tissue and administration of antifugals like Amphotericin B are keys to successful therapy.

A well informed consent has been obtained from the patient regarding publication of the case report including the clinical photographs. The specific consent had also taken from the patient to show his face photograph for the purpose of paper publication and medical research.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.