Journal of

eISSN: 2373-437X

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 1

1Egressa do Curso de Farmácia, Centro das Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Federal do Oeste da Bahia, Barreiras, Bahia, Brasil

2Docente do Centro das Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Federal do Oeste da Bahia, Barreiras, Bahia, Brasil

Correspondence: Dayane Otero Rodrigues, Docente do Centro das Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Federal do Oeste da Bahia, Barreiras, Bahia, Brasil, Tel (77) 9 8874-1879

Received: December 17, 2021 | Published: January 7, 2021

Citation: Silva ETM, Rodrigues DO. Risk factors for surgical site infection: challenges to public health. J Microbiol Exp. 2022;10(1):1-8. DOI: 10.15406/jmen.2022.10.00345

Surgical site infections are healthcare-related infections that succeeds post-surgical procedures in patients, associated with risk factors. Patients admitted in, healthcare facilities and medical institutions are vulnarable to these hospital associated due to lack of suitable infrastructure and hygiene protocols. The objective was to present the etiology and risk factors associated with the onset of surgical site infection, pointing out a critical view of the challenges and appropriate measures for its prevention in the country. The information was collected from various selective articles published between 2009 to 2020 indexed in databases, seeking to identify the etiology of surgical site infections and associated risk factors, followed by tabulating the data. Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae were among the most common perperators responsible for the development of hospital acquired clinical manifestation following a surgical procedure. Smoking, comorbidities, and the patient's advanced age, were other associated risk factors that were known to aggravate the clinical condition. The length of stay, type of surgery, and the use of invasive procedures were some extrinsic factors. The study revealed the role of bacteria from human microbiota of hospital origin as the main etiological agents of surgical site infections. It also addressed the need for reflection and adherence to measures to prevent and control this type of infection, and the imminent need for the development of National Programs for the Control of Hospital Infections in hospitals, qualifying multidisciplinary teams to face these challenges to public health.

Keywords: nosocomial infection, surgical site infection, risk factors, prevention

Hospital acquired infections (HAI) are a public health problem HAI increase patient stay, cost and lethality. These infections are considered as adverse events in the health services. It is resulting from infections that occur during the patient care process in hospitals and health care units.1 In this context, the presence of bacterial resistance, immunocompromised patients and irrational use of antibiotics are factors that can lead to an increase in HAI cases 2.

In Brazil, since 1997, it is mandatory that all hospitals maintain a National Nosocomial Infection Control Program (PNCIH) and a Nosocomial Infection Control Commission (CCIH),2,3 and the operation of the CCIH in the institution must rely on performance of qualified professionals in the areas of microbiology and epidemiology, carrying out active epidemiological surveillance.4

Surgical site infections (SSI) are one of the main types of HAI, in patients in intensive care units (ICUs), surgical wards and orthopedic wards.5 SSIs are the main causes of complications in post-surgical patients, which can promote a 60% increase in the time of hospitalization of patients and a consequent increase in the cost of treatment. In addition, this postoperative injury can cause physical consequences, which in the future may lead the individual to withdraw from social life,6 as retiring of the work.

SSIs are defined as a pathophysiological process that occurs after microbial invasion, facilitated by the inoculation of the pathogen during the surgical procedure, followed by multiplication and pathogenic development in human tissues.7 In addition, other aspects influence the development of SSIs, such as the virulence potential of the microorganism, as example the biofilm production, and factors associated with the patient, especially age, smoking, the presence of comorbidities such as diabetes and obesity, and risk factors extrinsic to the patient such as type of surgery and length of stay, among others.7,8

SSIs are characterized as infections related to surgical procedures, arising from the patient's exposure and contamination both to microorganisms from their own microbiota, such as Staphylococcus Coagulase Negatives, and those related to the hospital environment or contact with contaminated professionals, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococus ssp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacterias.9,10

Faced with the problem of HAIs, including SSIs, critical literature review studies such as this one are of fundamental importance to direct health professionals to a bibliographic source that provides assertive and clear information. From this perspective, the theoretical basis offered in our study aims to provide support for the promotion of interventions to control SSI in health units, contributing to the confrontation of these public health challenges. This study aimed to analyze the etiology and risk factors associated with the development of SSI in the literature through a critical assessment.

The present work was a critical literature review of scientific articles published from 2009 to 2020, emphasizing on the etiology and risk factors in accordance with SSIs, and relevant data validating the content were tabulated and discussed at the end. Scientific articles were selected through digital searches, using the following descriptors: surgical site infections and hospital infection. Articles published indexed in Pubmed, Scielo, Web of science, Medline, Google academic databases were selected, seeking to explain the problem from the theoretical references.As a way to guide the work, the following problem question was elaborated: “What are the epidemiological aspects and risk factors related to the development of SSI?” To guide the selection of articles, inclusion criteria (articles that presented the SSI rate and risk factors) and exclusion criteria (articles published outside of 2009 to 2020) were used (Figure 1).

The total of 20 selected articles were all observational, these types of studies can be divided into descriptive, which record the distribution of the disease according to the time, place and characteristics of individuals; and the analytical ones that identify the association between exposure and the disease.11 Among the analytical designs found in the analyzed articles, there was a predominance (45%) of cohort studies, 25% of the cross-sectional type and 0.2% of the case-control type , and in relation to the year of publication, the majority (45.0%) of the selected articles were from 2018 and 2019, 20.0% from 2011 to 2014 and 35.0% from 2016 and 2017 (Table 1).

|

Author |

Year |

Kind of study |

Type of surgery |

Risk factors |

|

VESCO NL et al |

2018 |

Retrospective, descriptive with quantitative approach |

Liver transplant |

Postoperative length of stay |

|

Use of immunosuppressant |

||||

|

Invasive Device Usage |

||||

|

Obesity |

||||

|

blood transfusion |

||||

|

marital status |

||||

|

KAHL ERPY et al |

2019 |

historical cohort |

Cardiac surgery |

Sexagenarian |

|

Arterial hypertension |

||||

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

||||

|

smoking |

||||

|

Obesity |

||||

|

Dyslipidemia |

||||

|

BELLUSSE GC et al |

2015 |

Transversal |

Surgery |

Obesity |

|

Neurological |

length of stay |

|||

|

blood transfusion |

||||

|

ANDRADE LS et al |

2019 |

Cohort |

Cardiac surgery |

Diabetes Mellitus |

|

Arterial hypertension |

||||

|

Obesity |

||||

|

Dyslipidemia |

||||

|

LERDUR P et al |

2011 |

Cohort |

Cardiac surgery |

Diabetes Mellitus |

|

Invasive Device Usage |

||||

|

smoking |

||||

|

Dyslipidemia |

||||

|

Arterial hypertension |

||||

|

GEBRIM CFL et al |

2014 |

Transversal |

Surgery clean |

Alcoholism |

|

Arterial hypertension |

||||

|

smoking |

||||

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

||||

|

MARTINS AJC et al |

2016 |

Cohort |

Urgency |

length of stay |

|

Emergency |

surgery time |

|||

|

Sexagenarian |

||||

|

blood transfusion |

||||

|

FERRAZ AAB et al |

2019 |

Cohort |

Surgery |

Diabetes Mellitus |

|

bariatric |

Obesity |

|||

|

smoking |

||||

|

MARTINS T et al |

2018 |

Transversal |

general surgeries |

length of stay |

|

MARTINS T et al |

2017 |

Transversal |

Contaminated surgeries |

Sexagenarian |

|

marital status |

||||

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

||||

|

Arterial hypertension |

||||

|

smoking |

||||

|

Invasive Device Usage |

||||

|

Use of immunosuppressant |

||||

|

length of stay |

||||

|

CHAGAS MQL et. al |

2017 |

case control |

Surgery |

Sexagenarian |

|

Orthopedic |

Invasive Device Usage |

|||

|

length of stay |

||||

|

Obesity |

||||

|

BYVALTSE VA et. al |

2018 |

Cohort |

Surgery |

length of stay |

|

Spine |

||||

|

FUSCO SFB et. al |

2016 |

Cohort |

Colon surgery |

length of stay |

|

Obesity |

||||

|

Alcoholism |

||||

|

smoking |

||||

|

Sexagenarian |

||||

|

ARAÚJO ABS et al |

2019 |

Transversal |

obstetric surgery |

length of stay |

|

Arterial hypertension |

||||

|

Obesity |

||||

|

smoking |

||||

|

BATISTA e CRUZ |

2019 |

Transversal |

Surgery |

Arterial hypertension |

|

General |

smoking |

|||

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

||||

|

Obesity |

||||

|

GEBRIM |

2016 |

Transversal |

Surgery |

hyperglycemia |

|

CFL et al |

General |

Asepsis of the operative field |

||

|

CIMA |

2017 |

Cohort |

Surgery |

Smoking |

|

RR et al |

colorectal |

Diabetes Mellitus |

||

|

DOS REIS RG |

2017 |

retrospective description |

Surgery |

length of stay |

|

et. al |

General |

Sexagenarian |

||

|

BARBOSA |

2011 |

Epidemiological |

Surgery |

length of stay |

|

MH et al |

retrospective |

General |

smoking |

|

|

antibiotic prophylaxis |

||||

|

Arterial hypertension |

||||

|

BICUDO SALOMÃO A et al |

2019 |

Cohort |

Surgery colorectal |

Longer length of stay |

Table 1 Presentation of scientific articles selected for the bibliographic review of the etiology and risk factors associated with surgical-site infections, in relation to authorship, year of publication, type of study methodology and surgery, and related risk factors to the development of ISC

In Table 1, in addition to the type of methodology used in the article and the year of publication, the risk factors and types of surgeries performed are presented, in order to present the variety of factors that may be associated with the development of SSI.

The occurrence of SSIs can be detected in the first 30 days after surgery, in case of superficial incisions, or within a year in deep incisions and in organ/cavity, if a prosthesis is placed and involves deep soft tissue in the incision, or involve any organ or cavity that has been opened or manipulated during surgery. The risk factors associated with this process may be related to patients, known as intrinsic factors, or to the procedures used in surgery and/or related to the hospital environment, characterized as factors extrinsic to patients.12

Assessment of intrinsic risk factors and patient characteristics

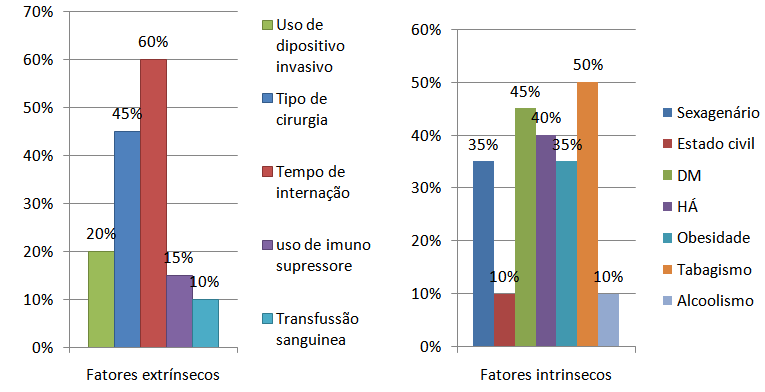

Progressing age is an important factor in the development of SSI, patients over the age of 60 years correspond to the age group that is more predisposed to develop SSI. In our study, children were not analyzed among the articles analyzed. Sixty-year-olds, because they have a deficiency in organic reserve and show a decrease in the functioning of the immune system, are people more susceptible to infections by microorganisms.13 This variable was significant in 35% of the evaluated articles, and the authors of these articles concluded that post- Surgical patients aged over 60 years are more likely to develop SSI and need more attention in the post-surgery period.

In a survey conducted with 150 patients at the Institute of Cardiology in Southern Brazil, 79.3% of those with surgical wounds were 61 years old, 74.7% were hypertensive, 44.7% diabetic and 40.7% had dyslipidemia.14 It is known that aging is a natural physiological process associated with the appearance of several chronic diseases that can hinder the recovery of post-surgical patients. Therefore, as a prevention measure for SSI, it is necessary to have a careful look at patients in their sixties, and those who have comorbidities that can influence their recovery.15

Comorbidities are one of the most relevant intrinsic factors when it comes to SSI, the ones with the highest prevalence in the reviewed studies were diabetes mellitus (DM), arterial hypertension (AH), obesity, smoking and alcoholism (Figure 2).15-17

Figure 2 Intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors related to the development of surgical site infection presented in scientific articles selected for the systematic and critical review of the etiology and risk factors of surgical site infections.

In 45% of the selected articles, DM was the prime risk factor for the development of SSI. DM is a chronic disease promoted by endocrine dysfunctions where the patient develops a state of absolute or relative hypoinsulinism and can influence the development of SSI through decreased collagen production and fibroblast proliferation, hindering the healing process in the post- surgical. In addition, DM hinders the nutrition and oxygenation of peripheral tissues, which leads to a decrease in systemic defense. Hyperglycemia also affects white blood cells, contributing to a decrease in the patient's immunity.18

In a survey conducted with 150 patients who had a surgical wound, it was identified that 46.3% of diabetics developed SSI (14). From this perspective, studies lead to the administration of preventive measures before surgery, such as monitoring blood glucose levels, keeping them between 80 to 120mg/dL. In cases of hyperglycemia, insulin administration continues to induce better therapy to reduce SSI cases.19 Several mechanisms are pointed out as important factors in reducing the healing process, among them, excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), decreased nitric oxide (NO), decreased response to growth factors (FG) and insulin signaling pathway proteins as with changes in vascularity , vasoconstriction.

Elevated blood pressure is also considered to be one of the intrinsic risk factors for the development of SSI as patients with lung disorders. In a study carried out at Hospital Escola in Southern Brazil,16 it was identified that 88.9% of patients who were diagnosed with AH progressed to SSI. Hypertension is a chronic disease that promotes dysfunctions in the body, affecting renal and cardiovasculares deficits, reducing peripheral circulation and affecting the immune system, which facilitates the development of SSI,13 being found in 45% of the articles analyzed.

Another important risk factor for the development of SSI is obesity, which was found in 45% of the articles. In a cross-sectional study,20 obesity was, among other chronic diseases, a risk factor for the development of SSI in 9.5% of patients undergoing surgery. Another study published in 2017,21 which aimed to assess risk factors for SSI, also showed a significant frequency of 21% of patients with obesity. In another cohort study with patients who underwent bariatric surgery, it was identified that there is a proportionality between the increase in the body mass index (BMI) range and the incidence of SSI cases. In this article, the author reports that patients with a BMI above 50 kilograms/square meters (kg/m2) indicated that they had a SSI index of 3.7%.22 Obese patients require greater attention in antibiotic therapy, given that the metabolism and excretion can affect the pharmacokinetics of the antibiotic, with a change mainly in the distribution volume and total clearance.23

Smoking is one of the main public health problems. This disease mainly affects the circulatory and respiratory systems and is responsible for the development of various types of cancer.24 According to some studies,14 chronic tobacco use also leads to the development of SSI. The smoking habit promotes some changes in the body that can interfere with postoperative recovery, including vasoconstriction of peripheral tissues and hypoxia, which contribute to the reduction in the formation of new blood vessels. In addition, it can reduce the production of collagen, the main component of the dermis that plays an important role at the end of the healing process, a stage named remodeling.25 This important comorbidity was found in 50% of the articles evaluated in this critical review. Hence, the urgent need for public policies with investment in health education is inferred, building the population's knowledge about this relationship between smoking and the development of SSI, to increase patients' awareness and autonomy in individual and collective care

Assessment of extrinsic risk factors

In all surgeries, there is a risk of contamination during and after the procedure causes the condition. The incision made in the skin during surgery corresponds to the entry point for various species of microorganisms, of exogenous or endogenous origin. The degree of contamination in a surgery is related to the anatomical region to be operated and the clinical status of the patient, and the classification of this degree of contamination must be performed by the surgeon at the end of the surgeries.

Regarding the articles analyzed, there is a predominance of potentially contaminated surgery, which are performed in places colonized by normal microbiota such as the digestive, respiratory and urinary tracts.26,27 Abdominal surgeries were the most frequent (45%) and are the most likely to develop ISC. Among the intestinal ones, cholecystectomy was in second place among the potentially contaminated ones and they are performed more frequently, with a prevalence of 30% among abdominal surgeries.12 In the report carried out by the National Healthcare Safety Network between the year 2015 to 2017, abdominal surgeries presented a very high frequency (54%) in cases of SSI in adult patients, compared to surgeries in other anatomical sites.28 The diversity of species and the large amount of microorganisms in the intestinal microbiota facilitate the contamination of the abdominal cavity and other anatomical sites in abdominais surgeries, being recommended the use of intestinal emptying, intestinal lavage, skin preparation, maintenance of preoperative fasting and use of antibiotics before abdominal surgeries. In addition to the need for patient awareness and humanized care from the health team in order to offer emotional support to the patient, since the emotional state can directly interfere with the postoperative evolution. This public health challenge can be faced by offering qualification courses to health teams, aiming to highlight the importance of humanization in patient care, in addition to the adequacy of the workload of health professionals, avoiding the emotional exhaustion of the team itself. hospital.

Among the studies analyzed, increased length of stay corresponded to one of the risk factors that presented a high frequency (60%) for the development of SSI, regardless of the type of surgery performed. This factor is related to the length of stay of post-surgical patients in hospitals, being exposed to contamination by environmental bacteria, which can lead to a worsening of the patient's prognosis and increase the cost of treatment, impacting the economic sector of public health and limiting the access of other patients to treatments.29,30 In addition, increased hospitalization time can lead to longer contact time between patients and health professionals, which will consequently lead to exposure to resistant microorganisms, requiring recurrent changes in treatment.15

In 20% of selected studies,15-17 it was validated that the use of invasive procedures and devices during surgery was correlated with the development of SSI. The articles showed that patients who acquired HAI and who were using an orotracheal tube, nasogastric tube, central venous catheter, indwelling urinary catheter, suction drain, dialysis catheter and tracheostomy had longer use due to complications of the devices.15 According to the literature, the increased permanence of central venous catheters in post-surgical patients is associated with the risk of developing SSI.17 In the study by Martins et al.16 with 46 patients who used CVC, two developed SSI, which is one of the alternatives for quick and immediate administration of the drug, but it must be installed by trained professionals in a safe and efficient way.

One of the selected articles pointed out the use of implants as one of the factors that predisposes to the occurrence of SSI, mainly related to the formation of biofilms on the implant surface, which can interfere with the patient's immunological defense and the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy.21 In addition , the bacteria that make up biofilms have the possibility of sharing genetic materials through conjugation, a worrying factor in the hospital environment as it facilitates the exchange of bacterial resistance genes, reducing the antimicrobial alternatives for treating SSI.26,27

Immunosuppressants are drugs that act by inhibiting cell division and decreasing the inflammatory process, they are indicated to prevent rejection of transplanted organs and to treat inflammatory diseases.31 Among the adverse effects of immunosuppressants, the risk of developing SSI is a fact pointed mainly in selective transplant surgery.31 The use of immunosuppressants, including tracrolimes, corticosteroids, microphenolate mofetil and mycophenolate sodium, was a significant factor for the development of infections in post-surgical patients (15) in 15% of the articles analyzed.

Etiology of SSI

The microorganisms present in the hospital environment and those that make up the microbiota of health professionals and patients are responsible for the development of SSI. Among the most prevalent microorganisms in promoting surgical site contamination are those of endogenous origin.32 In this context, knowledge of the etiology of SSI through literature review studies, such as this one, is of fundamental importance for the planning of measures of prevention and control of SSI. Table 2 shows the etiology of the microorganisms causing SSI among the six articles that presented etiological data.

|

Articles |

Year |

Micro-organisms identified |

|

VESCO NL |

2018 |

Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacterias, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa Acinetobacter baumanni |

|

KAHL ERPY |

2019 |

Serratia sp, Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase, Pseudomonas,Enterobacter, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter sp e Proteus mirabilis |

|

CHAGAS MQL et.al |

2017 |

Staphylococcus aureus, found one with the profile of Staphylococcus aureus resistant to methicillin (MRSA). |

|

Byvaltse VA |

2018 |

S. aureus e S.epidermidis. |

|

ARAÚJO ABS et al |

2019 |

Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacter aerogenes; Proteus mirabilis; Proteus vulgaris; Escherichia coli; Candida albicans; Klebsiella pneumoniae; Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

|

BARBOSA MH et al. |

2011 |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus , Escherichia coli. |

Table 2 Etiology of the microorganisms causing surgical site infection in the scientific articles selected for the literature review of the etiology and risk factors associated with surgical site infections

Source: Own authorship

S. aureus was the main etiological agent causing SSI, standing out in 85% of the selected articles. Samples of S. aureus and other microorganisms that colonize the skin of patients can become pathogenic after breaking the skin barrier and decreasing immunity, causing superficial or deep SSI.33 In this context, global guidelines recommend the adoption of prophylactic measures before surgery such as hand washing of the surgical team with antiseptic solutions for at least five minutes and bathing patients with neutral soap.34 In addition, antibiotic prophylaxis before surgery is indicated as a measure to intervene in possible cases of SSI 1.

In this scenario, the strains called methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) stand out, which can present a multi-resistant profile, which is currently one of the concerns of hospital teams due to the possibility of contamination of post-surgical patients.33-35 In the study developed with pediatric patients,21 the presence of one case of infection with MRSA was identified among the ten who presented SSI after implant surgery. The risk factors classified by the authors in this case were the presence of comorbidities and the duration of the surgery, which lasted eight hours. In this perspective, another team of researchers 23 found in a study with 700 patients undergoing clean surgery, that 10% had SSI caused by multiresistant microorganisms, and among them, 26.1% were identified as MRSA, among the risk factors they highlighted the irrational use of antibiotics in the hospital environment.

In the article that addressed the occurrence of SSI in urgent and emergency surgeries,29 the authors identified from isolated samples of wounds from post-surgical patients that approximately 8% were caused by P. aeruginosa, 5% by S. aureus and 3 % by E. coli. Samples of P. aeruginosa are commonly isolated in the hospital environment, mainly in humid places such as sinks, nebulizers and cleaning products, being considered one of the main causes of SSI and are associated with immunosuppressed patients, thus being opportunistic pathogens.36 The increase in cases of death from infections caused by P. aeruginosa is linked to the high frequency of antimicrobial resistance and, consequently, restriction of antibiotic therapy 37.

P. aeruginosa was found in 25% of the selected articles, and it has pathogenic characteristics and promotes serious infections. The use of high doses of antibiotics in postsurgical prophylaxis does not show additional benefit, but it increases the cost of treatment and allows the selection of resistant bacteria.23 Considering that P. aeruginosa is a pathogen of external origin, the adoption of measures prevention and control of infection, including hand hygiene of the health team during and after the surgical procedure would be feasible, and continue to be a challenge for public health in terms of adherence. It is necessary to carry out more awareness campaigns among health professionals for greater adherence to infection prevention and control measures.

E. coli also has a pathogenic action in cases of SSI. It is a component microorganism of the intestinal microbiota,38 which can promote diarrhea or extraintestinal diseases, and is involved in the development of SSI in cases of intestinal surgery.39,40 In this context, the high possibility of SSI occurring in intestinal tract surgery justifies the frequency of infections caused by E. coli. This microorganism was found in 66% of the articles analyzed and represents a worrying reason in the hospital area.

In an investigation carried out in 30 hospitals in China in 2018, the authors found an incidence of SSI in 4.8% of patients after 30 days of abdominal surgery, and among isolated microorganisms, E. coli prevailed in 32.5% of confirmed cases.40 In another study 39 there was also a high incidence (57.9%) of E. coli samples isolated from patients who presented SSI after rectal surgery. In this context, correct mechanical intestinal preparation with laxatives and use of prophylactic antibiotic therapy are fundamental preventive measures to be taken before intestinal tract surgeries, ensuring patient safety, as previously reported. This procedure aims to reduce the intestinal bacterial load, avoiding contamination of the patient by bacteria of intestinal origin at the time of incision, and the development of a possible SSI.41

K. pneumoniae is another enterobacteria that frequently causes SSI and was described in 50% of the articles evaluated. It can promote pneumonia, urinary infections, bacteremia, liver abscesses in immunocompromised individuals, among others. Recently, there has been an increase in infections also in healthy people by hypervirulent strains that are resistant to antibiotics.41 Regarding antibiotic resistance, K. pneumoniae that produces Carbapenemase (KPC) stands out, present among the most frequent bacteria in cases of SSI of patients undergoing cardiac surgery.14 Carbapenemases promote resistance to third and fourth generation cephalosporins and also to carbapenems, and the restriction of antimicrobial therapy in these cases increases the mortality rate.

In addition, there is a high recurrence of SSI caused by K. pneumoniae in post-cesarean patients, because this bacterium composes the microbiota of the lower genital tract, having the possibility of penetrating the abdominal incision performed during childbirth, thus, the hygiene measures in the pre- and post-surgical period, they are very necessary to prevent and control SSI rates.

SSIs are considered a worldwide public health problem, constituting one of the main HAIs, as they promote an increase in the time of treatment, the length of stay of post-surgical patients in hospitals and an increase in mortality. The frequency of SSI is a topic that has been questioned in the context of public health, and is a reason for scientific studies, and this critical review observed a frequency of less than 30% of cases of SSI, as pointed out by most of the revised articles.

The analysis of intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors indicated that the presence of smoking and comorbidities, and the patient's advanced age are one of the main intrinsic factors associated with the development of ICS and the length of stay, type of surgery and the use of an invasive procedure such as CVC and implants are important extrinsic factors. It is concluded that the association between risk factors related to the development of ICS increases the probability of aggravation of the infection picture.

The etiology associated with SSI cases points to common microorganisms in the human skin microbiota, such as S.aureus and SCN and those found in hospital environments such as P.aeruginosa. Knowledge of the etiology and resistance profile of SSI is of fundamental importance to health professionals for the planning, elaboration and adoption of measures for the prevention and control of SSI and in the treatment of these infections, since the increase in the frequency rates of Superresistant bacteria in the hospital environment associated with the development of SSI and HAI in general is a worrisome challenge to public health.

Adherence to SSI prevention and control measures are requirements to control both the frequency rates of SSI and to reduce the spread of resistant bacteria, with emphasis on the implementation of hand hygiene techniques for professionals and antisepsis of patients in pre and post -surgical, in addition to the rational use of antibiotic prophylaxis before the procedure. Confronting these public health needs must be based on the essentiality of the development of the PNCIH in hospitals, with the purpose of epidemiological surveillance and in the qualification of the multidisciplinary team, which must be able to identify risk factors and be able to intervene with the execution of infection prevention and control measures, enabling the patient to have a quick and safe surgical recovery.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2021 Silva, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.