Journal of

eISSN: 2373-437X

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 3

Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Correspondence: Dr. Rosni Ibrahim, Master of Pathology (MPath) (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia), Medical Doctor (MD) (University Sains Malaysia), Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia, Tel 03 89472363, Fax 03 89413802

Received: May 26, 2022 | Published: June 9, 2022

Citation: Saber H, Jasni A, Jamaluddin TZMT, et al. Diversity of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types among methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci (MR-CoNS). J Microbiol Exp. 2022;10(3):99-107. DOI: 10.15406/jmen.2022.13.00359

Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci (MR-CoNS) have become one of the important causes of nosocomial infections yet their clinical data in Malaysia is scarce compared to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec) genes play roles in their pathogenicity. This study thus aimed to determine species distribution, antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and SCCmec types among MR-CoNS isolated from blood cultures. A laboratory-based descriptive study was involved with non-probability sampling method. One hundred CoNS isolated from blood cultures were collected from Microbiology laboratory, Hospital Serdang and proceeded with phenotypic identification, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, mecA gene detection and SCCmec types classification. Staphylococcus epidermidis was the most common isolated MR-CoNS species. All 100 isolates were resistant to penicillin while being sensitive to vancomycin. The predominant SCCmec Type IV was observed in S. epidermidis which exhibited 100% resistant to penicillin and erythromycin besides dominating multiple antibiotic resistance. Meanwhile, the combination type was observed in type I & IVa (n=9, 9%) whereas 31 strains (31%) were non-typeable. Besides demonstrating MR-CoNS susceptibility pattern variations to commonly used antimicrobials for treatment of staphylococcal infections, this study could also preliminarily contribute in providing more local epidemiological data regarding MR-CoNS.

Keywords: antimicrobial susceptibility pattern, mecA, MR-CoNS, SCCmec, species distribution

CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci; MR-CoNS, methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci; SCCmec, staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec

Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) are normal flora that are found in mucous membranes and skin of mammals1 and have been reported causing nosocomial infections.2 They have the capability to produce biofilms for adherence to medical devices in hospitals, making them more successful in causing infections such as foreign body-related infections (FBRIs), preterm newborns infections and endocarditis.2,3 These biofilm-producing CoNS have been reported to increasingly become resistant to methicillin and multiple antibiotics groups such as lincosamides and macrolides.3,4 This matter can lead to serious clinical infections and becomes challenging in patients’ treatments in term of antibiotic prescription.2,5 Sanches et al.,6 had also studied that cross resistance occurred in methicillin-resistant staphylococci whereby 72.3% was observed in MR-CoNS.

Widely spread in hospitals, the most MR-CoNS species isolated include S. epidermidis and S. haemolyticus.7 These organisms harbour mecA gene encoding penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a) which allows only low binding to β-lactam antibiotics.2,8 The mecA gene is attained by SCCmec, a mobile genetic element.9 This element acquires two extensive components which are mec gene and cassette chromosome recombinase (ccr) gene complexes.10,11 The mec gene complex expresses methicillin resistance function whereas ccr and a few surrounding genes mediate integration and excision of SCCmec into and from the chromosome.10,11 Specific combinations of both complexes produce different types of SCCmec which include I-XI and an isolate may possess more than one type.11 Apart from that, SCCmec also possesses J regions that are applied in determining SCCmec subtypes, as well as a number of non-essential components which may carry additional antimicrobial resistance genes.10 Staphylococcal casette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types III, IV and V were prevalently found in MR-CoNS.11

Since the data related to MR-CoNS are limited in Malaysia, this study is conducted to determine the distribution of MR-CoNS species isolated from blood cultures, to observe their antimicrobial susceptibility profile, to detect their SCCmec types and to determine the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of the SCCmec types. The outcomes from this research particularly on the SCCmec genes, can be a set of preliminary data that may be used for further research to assist on management of MR-CoNS infections.

Bacterial identification

Staphylococci isolated from blood cultures were cultured on blood agar (BA) and the colony morphology was observed. They were subjected to phenotypic identification by performing gram-staining, catalase and coagulase tests. They were further identified up to species by using API® Staph kit. The results were interpreted according to the reference table provided and species was identified by entering the results in apiwebTM website. The CoNS isolates were stored in cryobeads (CryoCareTM) for further use.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method was performed using nine antibiotic discs (Oxoid, UK); cefoxitin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, erythromycin, fucidic acid, gentamicin, penicillin, rifampicin and vancomycin. Zones of inhibition were observed and referred with the interpretive criteria according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2016 (Table 1). Isolates resistant to cefoxitin (30 µg) (≤21 mm clear zone diameter) were indicated as MR-CoNS and kept aside for further confirmation.

Antimicrobial Agent (µg) |

Zone Diameter Interpretive criteria (nearest whole mm) |

|

Sensitive |

Resistant |

|

Penicillin (10) |

≥ 29 |

≤ 28 |

Cefoxitin (30) |

≥ 22 |

≤ 21 |

Gentamicin (10) |

≥ 15 |

≤ 12 |

Erythromycin (15) |

≥ 23 |

≤13 |

Clindamycin (2) |

≥ 21 |

≤ 14 |

Rifampicin (5) |

≥20 |

≤ 16 |

Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75) |

≥ 16 |

≤ 10 |

Fucidic acid (10) |

≥ 22 |

≤ 14 |

Vancomycin (30) |

≥ 22 |

≤ 14 |

Table 1 Antimicrobial agents and their respective zone diameter interpretive criteria for coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS)

(Source: Adapted from CLSI 2016)

Detection of mecA gene

Genomic DNA was extracted by using AxyPrep Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Axygen, USA) and the DNA purity was measured by using NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, USA). The presence of mecA gene was detected by using forward (5′-TCCAGATTACAACTTCACCAGG-3′) and reverse (5′-CCACTTCATATCTTGTAACG-3′) primers as proposed by Ghaznavi-Rad et al.12 Positive and negative controls were S. epidermidis ATCC 35984 and S. epidermidis ATCC 12228, respectively. A total of 20µL PCR mixture contained 10µL master mix (Thermo Scientific, USA), 10µM 0.5µL of each primer, 1µL DNA template and 8µL nuclease free water. The reaction was carried out in Bio-Rad MyCyclerTM, USA starting with 1 cycle of initial denaturation at 98°C for 30 seconds followed by 28 cycles of denaturation (98°C, 10 seconds), annealing (52°C, 30 seconds), and extension (72°C, 30 seconds) and finally 1 cycle of final extension at 72°C before holding at 4°C. The PCR amplicons were performed gel electrophoresis (58 V, 120 minutes) in 1.4% agarose gel containing 0.5µl gel stain (Bioteke, China). DNA ladder of 100 bp (Vivantis, Malaysia) was used as a standard marker. The gel was visualized under UV light and the image was captured using gel imager (Major Science, USA). One hundred confirmed mecA-positive CoNS (MR-CoNS) isolates were stored for further gene detection.

Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec) Typing

A multiplex PCR assay was first optimized by using primers of respective control strains as described in Table 2. A total of 20µL PCR mixture contained 10µL multiplex PCR master mix (Thermo Scientific, USA), 10µM 0.2µL of respective forward and reverse primers for each staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type including mecA, 1µL DNA template and 3.8µL nuclease free water. It was performed by using Bio-Rad MyCyclerTM (USA) thermocycler beginning with an initial denaturation step at 98°C for 30 seconds followed by 28 cycles of denaturation (98°C, 10 seconds), annealing (52°C, 30 seconds), and extension (72°C, 30 seconds) and finally 1 cycle of final extension at 72°C before holding at 4°C. Gel electrophoresis (58 V, 120 minutes) in 1.4% agarose gel containing 0.5µl gel stain (Bioteke, China) was performed with 100 bp plus DNA ladder (Vivantis, Malaysia) was used as a standard marker. The gel was visualized under UV light and the image was captured using gel imager (Major Science, USA). Representative strain of each successfully detected SCCmec types was sent to MyTACG (Malaysia) for sequencing. Sequencing analysis was performed accordingly by using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTn) available in National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) website.

Primer |

Oligonucleotide sequence (5’ – 3’) |

Control strain |

References |

Type I |

F: GCTTTAAAGAGTGTCGTTACAGG |

NCTC10442 |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(613 bp) |

R: GTTCTCTCATAGTATGACGTCC |

Zhang et al.,13 |

|

McClure-Warnier et al.,14 |

|||

Type II |

F: GATTACTTCAGAACCAGGTCAT |

N315 |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(287 bp) |

R: TAAACTGTGTCACACGATCCAT |

Zhang et al.,13 |

|

McClure-Warnier et al.,14 |

|||

Kondo et al.,15 |

|||

Type III |

F: CATTTGTGAAACACAGTACG |

85/2082 |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(243 bp) |

R: GTTATTGAGACTCCTAAAGC |

Zhang et al.,13 |

|

McClure-Warnier et al.,14 |

|||

Milheirico et al.,16 |

|||

Type IVa |

F: GCCTTATTCGAAGAAACCG |

CA05 |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(776 bp) |

R: CTACTCTTCTGAAAAGCGTCG |

Zhang et al.,13 |

|

McClure-Warnier et al.,14 |

|||

Type IVb |

F: AGTACATTTTATCTTTGCGTA |

8/6-3P |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(1000 bp) |

R: AGTCATCTTCAATATGGAGAAAGTA |

Zhang et al.,13 |

|

McClure-Warnier et al.,14 |

|||

Type IVc |

F: TCTATTCAATCGTTCTCGTATT |

MR108 |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(677 bp) |

R: TCGTTGTCATTTAATTCTGAACT |

McClure-Warnier et al.,14 |

|

Ma et al.,17 |

|||

Type IVd |

F: AATTCACCCGTACCTGAGAA |

JCSC4469 |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(1242 bp) |

R: AGAATGTGGTTATAAGATAGCTA |

McClure-Warnier et al.,14 |

|

Kondo et al.,15 |

|||

Type IVg |

F: TGATAGTCAAAGTATGGTGG |

JCSC 6673 |

Milheirico et al.,16 |

(792 bp) |

R: GAATAATGCAAAGTGGAACG |

||

Type IVh |

F: TTCCTCGTTTTTTCTGAACG |

JCSC 6674 |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(663 bp) |

R: CAAACACTGATATTGTGTCG |

Milheirico et al.,16 |

|

Type V |

F: GAACATTGTTACTTAAATGAGCG |

WIS |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(325 bp) |

R: TGAAAGTTGTACCCTTGACACC |

Zhang et al.,13 |

|

McClure-Warnier et al.,14 |

|||

Type VI |

F: GAGGGATGGAGTGGATGAGATA |

HDE288 |

Chen et al.,18 |

(415 bp) |

R: GGTGAAGGACGATGAATGAGTAG |

||

Type VIII |

F: CGAAGTAGTGATAGCCGCATAG |

C10682 |

Chen et al.,18 |

(901 bp) |

R: GTATGGATGATCGGGCGTTAG |

||

mecA |

F: TCCAGATTACAACTTCACCAGG |

S. epidermidis |

Ghaznavi-Rad et al.,12 |

(162 bp) |

R: CCACTTCATATCTTGTAACG |

ATCC 35984 |

|

Table 2 Details of primers used for detection of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec) types

Note: F, forward primer; R, reverse primer

Species distribution in MR-CoNS

Among 100 MR-CoNS, Staphylococcus epidermidis was the most common isolated species (n=56, 56%) followed by Staphylococcus haemolyticus (n=19, 19%), Staphylococcus chromogenes (n=12, 12%), Staphylococcus xylosus (n=6, 6%), Staphylococcus hominis (n=5, 5%), Staphylococcus capitis (n=1, 1%) and Staphylococcus cohnii (n=1, 1%) (Table 3).

Species |

Number of Isolates (n) |

Percentage (%) |

S. epidermidis |

56 |

56 |

S. haemolyticus |

19 |

19 |

S. chromogenes |

12 |

12 |

S. xylosus |

6 |

6 |

S. hominis |

5 |

5 |

S. capitis |

1 |

1 |

S. cohnii |

1 |

1 |

Total |

100 |

100 |

Table 3 Species distribution among 100 methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci (MR-CoNS) isolated from blood cultures

Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern

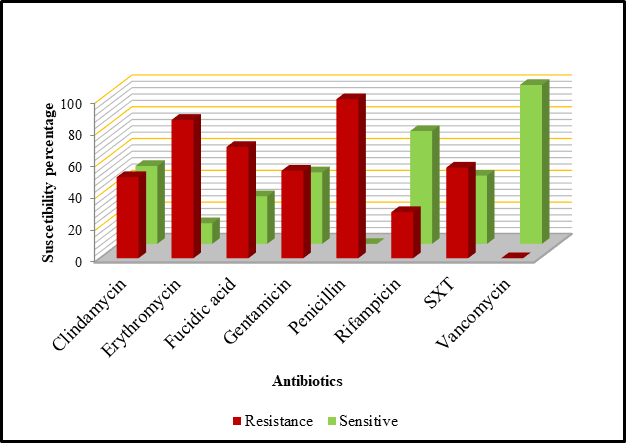

Figure 1 shows the susceptibility pattern against nine antibiotic discs among the cefoxitin-resistant CoNS isolates. One hundred percent resistance was observed towards cefoxitin and penicillin, followed by erythromycin (87%), fucidic acid (70%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) (57%), gentamicin (55%), clindamycin (51%) and rifampicin (29%). Meanwhile, all isolates were susceptible to vancomycin.

Figure 1 Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of 100 methicillin-resistant coagulase negative staphylococci (MR-CoNS) isolates.

Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec) Typing

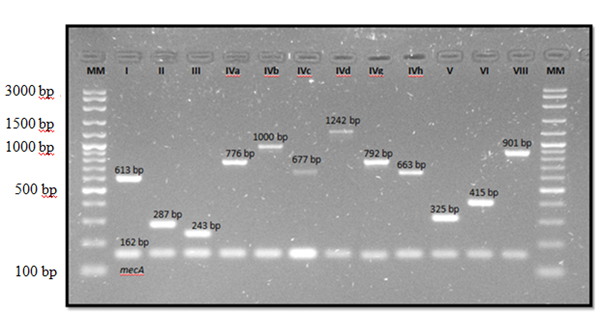

Twelve reference strains plus methicillin-resistance control strain (S. epidermidis ATCC 35984) were used as summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Multiplex PCR products of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types in control strains. MM, DNA molecular mass size marker (VC 100 bp Plus DNA ladder, Vivantis).

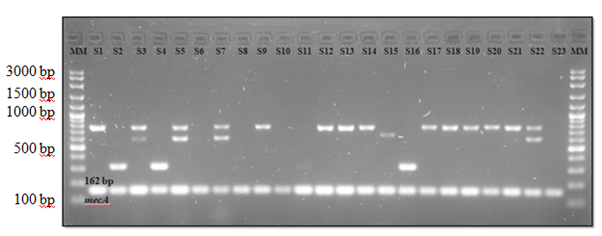

As shown in Table 4, the most common SCCmec type was IVa (n=32, 32%) followed by VIII (n=8, 8%) and V (n=6, 6%). Other types were also detected but with low distribution; type III (n=3, 3%), IVh (n=2, 2%), I (n=2, 2%) and IVb (n=1, 15). Fifteen (15%) combination types were detected as well with type I & IVa being the most common (n=9, 9%) followed by IVa & VIII (n=2, 2%), V & VIII (n=2, 2%) and II, V & VIII (n=2, 2%). Another 31 strains (31%) were non-typeable. Table 4 also shows that type IVa was most commonly found in S. epidermidis (n=27, 48.2%) compared to in other species. Figure 3 shows the distribution of SCCmec types among 23 S. epidermidis representative strains.

SCCmec Type (n) |

MR-CoNS Species |

||||||

S. epidermidis |

S. haemolyticus |

S. chromogenes |

S. xylosus |

S. hominis |

S. capitis |

S. cohnii |

|

(n=56) |

(n=19) |

(n=12) |

(n=6) |

(n=5) |

(n=1) |

(n=1) |

|

I (2) |

2 (3.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

III (3) |

2 (3.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (20) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

IVa (32) |

27 (48.2) |

3 (15.8) |

2 (16.7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

IVb (1) |

1 (1.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

IVh (2) |

2 (3.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

V (6) |

5 (8.9) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (100) |

0 (0) |

VIII (8) |

0 (0) |

1 (5.3) |

2 (16.7) |

3 (50) |

1 (20) |

0 (0) |

1 (100) |

I & IVa (9) |

9 (16.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

IVa & VIII (2) |

0 (0) |

1 (5.3) |

1 (8.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

V & VIII (2) |

0 (0) |

2 (10.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

II, V & VIII (2) |

0 (0) |

2 (10.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Non-typeable (31) |

8 (14.3) |

10 (52.6) |

7 (58.3) |

3 (50) |

3 (60) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Table 4 Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec) types distribution among MR-CoNS species

Note: Percentages in brackets show the proportion of MR-CoNS isolates of a particular species harbouring one SCCmec type

Figure 3 Detection of SCCmec types in S. epidermidis strains. S1, 9, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, type IVa (776 bp); S2, 4, 16, type V (325 bp); S3, 5, 7, 22, type I & IVa (613 bp & 776 bp); S15, type IVh (663 bp); S6, 8, 10, 11, 23, non-typeable; MM, DNA molecular mass size marker (VC 100 bp Plus DNA ladder, Vivantis). S1-S23 were representative strains of S. epidermidis.

Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types

Type IVa which was the most common type found in this study exhibited high resistance rates towards both erythromycin (n=32, 100%) and penicillin (n=32, 100%), followed by fucidic acid (n=25, 78.1%) and clindamycin (n=24, 75%) (Table 5). Type IVa was observed to predominantly dominating multiple antibiotic resistance compared to other types. While three combinations of I & IVa (n=9), IVa & VIII (n=2) and II, V, VIII (n=2) showed 100% resistance rates towards erythromycin, four combinations of I & IVa (n=9), IVa & VIII (n=2), V & VIII (n=2) and II, V, VIII (n=2) showed 100% resistance towards penicillin. As for the 31 non-typeable strains, all of them exhibited 100% resistance to penicillin followed by erythromycin (n=25, 80.7%) and fucidic acid (n=21, 67.7%). They also showed resistance to multiple antibiotics.

Antibiotics (n) |

SCCmec Type |

|||||||||||

I |

III |

IVa |

IVb |

IVh |

V |

VIII |

I & Iva |

IVa & VIII |

V & VIII |

II, V & VIII |

Non-typeable |

|

(n=2) |

(n=3) |

(n=32) |

(n=1) |

(n=2) |

(n=6) |

(n=8) |

(n=9) |

(n=2) |

(n=2) |

(n=2) |

(n=31) |

|

Clindamycin |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

24 (75.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (75) |

9 (100) |

1 (50.0) |

0 (0) |

1 (50.0) |

10 (32.3) |

Erythromycin |

1 (50.0) |

3 (100) |

32 (100) |

1 (100) |

2 (100) |

2 (33.3) |

8 (100) |

9 (100) |

2 (100) |

0 (0) |

2 (100) |

25 (80.7) |

Fucidic acid |

1 (50.0) |

3 (100) |

25 (78.1) |

0 (0) |

1 (50.0) |

3 (50.0) |

7 (87.5) |

7 (77.8) |

1 (50.0) |

0 (0) |

1 (50.0) |

21 (67.7) |

Gentamicin |

2 (100) |

3 (100) |

19 (59.4) |

0 (0) |

1 (50.0) |

2 (33.3) |

5 (62.5) |

8 (88.9) |

1 (50.0) |

0 (0) |

1 (50.0) |

13 (41.9) |

Penicillin |

2 (100) |

3 (100) |

32 (100) |

1 (100) |

2 (100) |

6 (100) |

8 (100) |

9 (100) |

2 (100) |

2 (100) |

2 (100) |

31 (100) |

Rifampin |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

14 (43.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (25.0) |

1 (11.1) |

1 (50.0) |

0 (0) |

1 (50.0) |

10 (32.3) |

SXT |

1 (50.0) |

3 (100) |

18 (56.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

7 (87.5) |

9 (100) |

2 (100) |

0 (0) |

1 (50.0) |

16 (51.6) |

Vancomycin |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Table 5 Distribution of SCCmec types in MR-CoNS according to resistance pattern to antibiotics

Note: Percentages in brackets show the proportion of MR-CoNS of one particular SCCmec type being resistant to an antibiotic. Percentages do not add to give a value of 100 since one isolate can be resistant to more than one antibiotic

In this present study, S. epidermidis (56%) was found as the most common isolated MR-CoNS species followed by S. haemolyticus (19%). These results are similar to the findings reported by Khan et al.,19 whereby S. epidermidis was the most common isolated strain (75.8%) in clinical blood cultures followed by S. haemolyticus (11.1%). Sani et al.,20 found that S. epidermidis was the most prevalent species identified in University Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC) in 2009 while Pereira and Cunha21 reported that 82% of their isolated strains from neonatal blood cultures in a Brazilian hospital were S. epidermidis. In one Turkish hospital, out of 200 CoNS isolated from blood samples between year 1999 to 2006, S. epidermidis was reported as the most prevalent species (n=87) followed by S. haemolyticus (n=23).22 Supported by Becker et al.,2 S. epidermidis often colonizes foreign bodies and associated with bloodstream infections since it is a major skin colonizer that can easily contaminate blood. However, studies done in India23 and Thailand24s reported contrast results with S. haemolyticus being the most common species isolated before S. epidermidis.

Distribution percentages in S. chromogenes (12%), S. xylosus (6%), S. hominis (5%), S. capitis (1%) and S. cohnii (1%) were also found similar to several studies. Staphylococcus chromogenes was once described as a rare human pathogen but it is becoming a more serious nosocomial pathogen and has been implicated in blood stream infections among a number of patients in Nigeria, whereby 5% has been isolated from clinical samples.25 On the other hand, Staphylococcus xylosus has been reported as an important cause of bacteraemia in India.26 Azih and Enabulele27 found S. xylosus (10%) as the only CoNS species isolated from blood samples. Meanwhile, 4% of S. hominis was isolated from blood samples in Iran.7 Chaves et al.,28 found that S. hominis was the main cause of sepsis in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in Spain and Roy et al.,29 observed that methicillin-resistance S. hominis has been causing septicaemia among cancer patients. As for S. capitis, 3% was isolated from blood samples.7 Being one of the emerged nosocomial pathogens, 28.6% S. capitis was known to cause prosthetic joint infections,30 endocarditis31 and catheter-related bacteraemia.32 Whilst, S. cohnii has been isolated in the cases of bacteraemia and septicaemia to patients with colon and pressure ulcers.33,34 This strain has the least distribution (1%) among blood samples in Iran.7 All of these studies showed that factors such as geography, environments and types of sample may influence the epidemiology of health-care associated CoNS and their species distribution.23,23,35,36

In terms of antimicrobial susceptibility, three antibiotics with the highest resistance which are penicillin, erythromycin and fucidic acid, are to be mainly discussed. This recent study found that MR-CoNS were most highly resistant towards penicillin and erythromycin. This resistance pattern was similar to a study conducted by Sani et al.,20 which found that their CoNS were most commonly resistant to penicillin (98.7%) followed by erythromycin (60%). This is due to the high use of penicillin as an old drug, to treat staphylococcal infection while erythromycin and clindamycin are commonly used to treat outpatients. As other studies also reported, majority of CoNS which are resistant to methicillin are well adapted to other antibiotics.20,37,38 Positive-mecA CoNS strains were reported to be more resistant to antibiotics such as erythromycin and clindamycin compared to mecA-negative strains.22,39 Akpaka et al.,40 mentioned that CoNS were reported to be inherently resistant to penicillin and its prolonged usage helps in increasing the number of methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Erythromycin and clindamycin were reported to be commonly used in treating outpatients41 thus may have contributed in the increasing rate of resistance in both antibiotics among MR-CoNS. Meanwhile, Duran et al.,42 however obtained highest resistance to clindamycin (54.7%), followed by SXT (40.9%) and erythromycin (38.4%) among their 159 CoNS strains. They concluded that such difference in level of resistance as compared to other studies occurred because the antibiotics have been widely used in their region.42 In India, Ahmed et al.,43 had observed 100% resistance in co‑trimoxazole besides penicillin. Similar results obtained by Murugesan et al.,44 where the highest resistance was to cotrimoxazole (n= 13, 26%) which these contrary findings may be because of their isolates which were isolated from community settings that may have different reactions towards antimicrobial susceptibility pattern.

On top of that, 70% of the isolates were resistant to fucidic acid which made it as the third most percentage of resistance. It could be due to the frequent use of fucidic acid in treating outpatients especially for skin infections. Resistance rate in fucidic acid has been increasing in developed regions such as in Australia and some parts of Europe due to its common use in treating staphylococcal skin infections.45 Castanheira et al.,46 reported that higher rate of fucidic acid resistance occurs in MR-CoNS (9.2%) than in methicillin-susceptible CoNS (5.2%). Howden and Grayson45 as well as Castanheira et al.,46 concluded that factors such as methicillin-resistance gene harbouring and frequent use of fucidic acid in treatments help to contribute to the high rate of fucidic acid resistance. In comparison to above findings, Murugesan et al.,44 observed only 10% of fucidic acid resistance among their MR-CoNS isolated from nasal swabs in community setting.

Additionally, the finding in respect to 100% sensitivity towards vancomycin reported in this recent study was supported by Sani et al.20, Ahmed et al.,43 and Bhatt et al.,47 where all of their CoNS isolates were also susceptible to vancomycin. As mentioned by Al-Tayyar et al.48, antibiotics such as vancomycin and rifampicin are still used in preventing and treating CoNS infections until recently. As can be seen, the variation of antimicrobial resistance pattern may be influenced by inappropriate use of antibiotics to treat staphylococcal infections in which some of the patients might seek treatment as outpatients where the compliance is difficult to assess. This is supported by other studies that also observed an increasing trend of resistance due to factors such as poor infection control practices, bacterial pathogenicity and inappropriate use of antibiotics.49,50

In regards to the distribution of SCCmec types, similar outcome was found between this study and Garza-Gonzalez et al.,51 whereby the most detected SCCmec type was IVa. Mert et al.,52 had reported that generally, majority of MR-CoNS isolated from blood harboured SCCmec type IV (n=65, 24.9%) while Sani et al.,53 found that type IV as the most common (42%) in clinical samples. In contrast, type III was observed as the most commonly distributed in Brazil in which more than 50% were isolated from blood cultures from 1990 to 2009.21 Previous study by Zong et al.,11 also reported that either single or in combination, the most common type among their 84 MR-CoNS was type III (n=33, 39.3%) followed by V (n=31, 36.9%) and IV (n=17, 20.2%). Similar findings reported by Chen et al.,54 whereby the predominant type was type III followed by type V. The differences in SCCmec type distribution in MR-CoNS in this present study as well as other previous studies were probably due to host species and geographical regions as also reported by Zong et al.11 For instance, Wisplinghoff et al.,55 and Ibrahem et al.,56 reported that type IV has been found the most in Finland (33%) and United Kingdom (36%) respectively whereas type III was the predominant type (52%) in southern Brazil.57 Meanwhile, type II was the most prevalent type in China58 and Nigeria.59 In addition, the SCCmec type distribution may also probably be influenced by horizontal gene transfer of SCCmec which eventually results in new variants with enhanced antimicrobial resistance and virulence level.60 On the other hand, point mutation, recombination, and deletion, with host & environmental pressures, may also lead to evolution of SCCmec.61

In this present study, type IVa was most widely distributed in S. epidermidis. From Figure 3, it can be seen that type IVa was mostly detected among the 23 representative of S. epidermidis strains. Similarity found in a study by Jamaluddin et al.,62 that reported type IVa as the predominant type in S. epidermidis isolated from clinical samples in Japan. Barbier et al.,63 also described that type IVa was very common in S. epidermidis. Ruppe et al.,64 that suggested an association of type IV with S. epidermidis, further clarified that settings, sampling method, demographic information and number of patients may influence the SCCmec type distribution. Type IVa was also common among S. haemolyticus (n=3, 15.8%) and S. chromogenes (n=2, 16.7%) strains. This is probably due to their serious association with human infections.25,65 As for the other species that did not harbour type IVa in this recent study, this may be because their isolates number were too low compared to S. haemolyticus and S. chromogenes. This study also found that combination type of I & IVa (n=9, 16.1%) was all harboured by S. epidermidis while S. haemolyticus and S. chromogenes respectively harboured combination type of IVa & VIII (n=1, 5.3% and n=1, 8.3%). On the other hand, type V & VIII (n=2, 10.5%) and II, V & VIII (n=2, 10.5%) were fully harboured by S. haemolyticus.

There were a few limitations in this present study which include the inability of the multiplex PCR to detect five SCCmec types (IVc, IVd, IVg, VI and VII) where these types could be harboured by the 31 non-typeable strains. This may be due to errors such as the cassette chromosome recombinase (ccr) genes might have been accidently deleted, unrecognized or their primer regions were mutated in which these factors may happen beyond our concern thus lead to unsuccessful type detection.66 In addition, certain types such as VI and VII have not yet been identified in MR-CoNS.11,56,63,64 The method however, could still detect quite a variety of types compared to some previous studies that were able to detect lesser types.

In this present study, multiple antibiotic resistance was commonly seen in SCCmec type IVa probably due to the influence of high number of MR-CoNS strains dominating this particular type. These observations were also reported by other studies summarizing that the difference in resistance pattern among SCCmec types may be influenced by factors such as number of isolates, type of predominant species and isolation settings.23,44

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among SCCmec types were also observed. Similarly, Sani et al.,53 also observed that more than half of their MR-CoNS strains (56.3%) had the most resistance towards penicillin (81.2%) and erythromycin (53.3%), with SCCmec type IVa being the predominant type. Murugesan et al.,44 however did not find type IVa as the most common type but this particular type did indicate multiple antibiotic resistance with 5/9 antibiotics resistance proportion. They further reported that type I was the type possessing multiple antibiotic resistance (7/9 antibiotics). This was probably due to the significant high number of SCCmec type I isolates (n=15, 30%).44 Ghosh et al.,23 also found that the most detected type in their study which was type I (61.4%) had strong resistance rates towards tested antibiotics, besides obtaining S. haemolyticus (n=29, 64.4%) as the most isolated species above S. epidermidis (n=6, 26.1%) among 44 MR-CoNS isolates.

In this recent study, Staphylococcus epidermidis was found as the most common isolated methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci (MR-CoNS) from blood samples and they exhibit variation results in antimicrobial resistance pattern. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type IVa was the most common type detected and it showed 100% resistance towards penicillin and erythromycin followed by multiple antibiotic resistance towards other tested antibiotics. It was also predominantly found in S. epidermidis. Even though coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) are low pathogenic Gram positive bacteria, but they may cause significance serious infection in high risk group of patients. Usage of vascular catheter and prosthetic devices are among the risk associated with CoNS infection. However, that information was not included in the research objectives of this study. Findings from the current research provides local baseline of epidemiological data regarding MR-CoNS species distribution, antimicrobial susceptibility profile and distribution of SCCmec that may aid future research. Perhaps more clinical data should be included in further studies to determine the clinical significance of CoNS that may help the management of patients.

A bunch of appreciation to my supervisory committees, Dr Rosni Ibrahim, Dr. Azmiza Syawani Jasni and Dr. Tengku Zetty Maztura Tengku Jamaluddin for the endless supports throughout the journey of this research. Special thanks to Professor Dr. Keiichi Hiramatsu and Associate Professor Dr. Yuki Uehara from Juntendo University (Tokyo), Professor Dr. Robert Daum from University of Chicago (Illinois), Professor Dr. Anders Rhod Larsen from Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen), Professor Dr. Herminia de Lencastre from The Rockefeller Univeristy (New York) and Associate Professor Dr. Neoh Hui Min from UKM Medical Molecular Biology Institute (Kuala Lumpur) for giving permission and assistance in providing SCCmec types controls. Thank you to the Head of Microbiology Unit, Pathology Department of Hospital Serdang (Selangor), Dr. Lailatul Akmar Mat Nor as well as other staff for their cooperation and guidance throughout the sample collection process. We would like to acknowledge National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC) UPM for providing ethical approvals. Not forgetting, UPM IPS Grant (9507200) for the financial support throughout this project.

RI, AJ and TZMTJ formulated the ideas of this study, supervised and advised the study design. RI, AJ, TZMTJ and HS developed the study concept and designed the experiments. HS planned and performed the experiments. RI and HS participated in manuscript drafting and data analysis. RI, AJ, TZMTJ and HS were involved with the manuscript preparation, editing and finalizing. All authors read and approved the finalized manuscript.

This research was funded by Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) IPS Grant, number 9507200.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the university (Ref. No: (05) KKM/NIHSEC/P16-1032.

All data generated and analysed in this study are included in this published article.s

All authors had experienced no competing interest in conducting this study.

©2022 Saber, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.