Journal of

eISSN: 2373-437X

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 4

Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, México

Correspondence: Amelia Portillo-López, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. Km 103 carretera Tijuana, Ensenada. Ensenada, B.C. México, Tel 526461528211

Received: June 30, 2021 | Published: July 19, 2021

Citation: Portillo-López A, Hoyos-Salazar L. Detection of Giardia duodenalis in sewage of Ensenada, Baja California, México. J Microbiol Exp. 2021;9(4):121-126. DOI: 10.15406/jmen.2021.09.00332

G. duodenalis is a pathogenic protozoan that affects animals and humans. This microorganism is transmitted by the fecal-oral route when it is ingested contaminated water or food. Giardia cysts are infectious, resistant to extreme environmental conditions, and their presence in sewage depends on the technologies used in the treatment plants. This study analyzes G. duodenalis and total (TC) and fecal (FC) coliforms in wastewater effluents of treatment plants (The Northeast, Gallo, Naranjo, Sauzal) and Emilio López Zamora dam of Ensenada Baja California. Water samples were taken monthly from June to November of 2019. Giardia was detected using the direct immunofluorescence (DFA) technique. TC and FC quantification were carried out according to the official Mexican standard (NOM-001-SEMARNAT-1996). Giardia was observed in Gallo (80-280 cysts/L), Sauzal (0-240 cysts/L), and Naranjo (0-360 cysts/L) effluents from July to November. FC was generally within the official standard (NOM-003), less than 1000 FC/100 mL for waters that will have indirect or occasional contact with the human being. Except for Naranjo effluent, where coliforms exceeded 1800 NMP/100 mL.

Keywords: parasites, sewage, coliforms, contamination, protozoan

Diseases transmitted by contaminated water occur mainly in developing countries, whose populations lack sewage, causing outbreaks in entire communities and sometimes epidemics.1 Among the most common organisms found in polluted waters is the protozoan Giardia duodenalis (syn; G. lamblia and G. intestinalis).2,3 This microorganism is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. Giardia cyst is the infectious and latent form within its life cycle, and it is released into rivers, lakes, and oceans through sewage and stormwater discharges that carry pollutants. Once a person becomes infected, the trophozoite hatches from the cyst and settles and reproduces in the duodenum causing abdominal spasms, anorexia, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea.3,4

Giardia infections tend to be more common among children than adults. Giardia has a high prevalence in developing countries (incidence rate of 6–42%) and underdeveloped countries (8-30%).1,4 In México, the incidence rate in 2015 was 9.57cases per 1000 inhabitants.5 The presence of this parasite in sewage has been reported in many studies around the world.6-8 However, it never has been studied in Ensenada city, and few studies have been done in México. The objective of this work was to detect the presence-absence of G. lamblia cysts in the effluent of treatment plants that are principally discharged into the seawater o reused for agriculture purposes. In addition, the presence of total and fecal coliform bacteria was evaluated as a traditional indicator of water contamination. Both organisms provide us information on the quality of the water discharged into the environment.

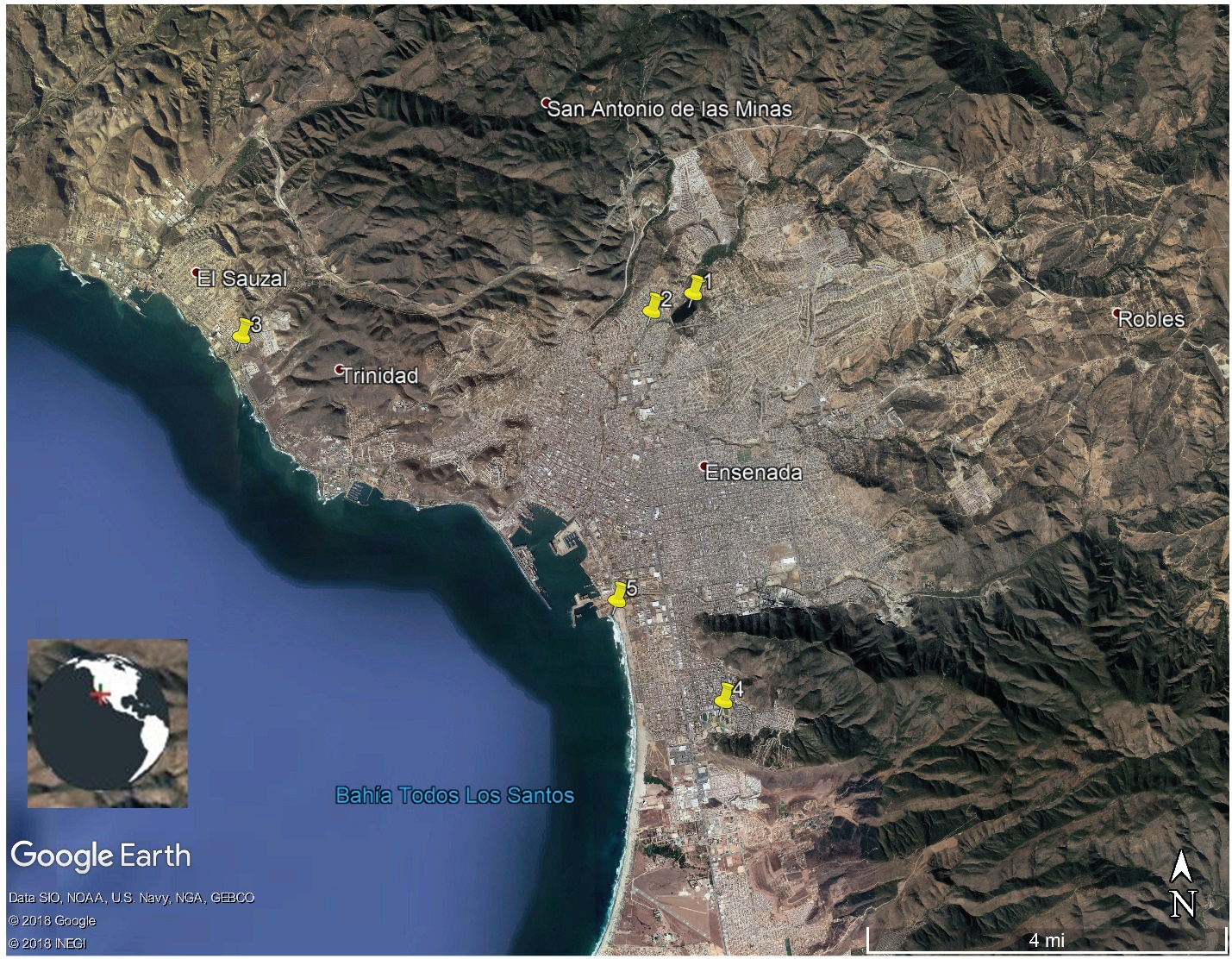

Water samples were taken for six months from outflows of sewage plants; The Northeast (31°54´16´ N, 116°36´34´O; treatment with activated sludge and disinfection with UV light and chlorine), Gallo (31°50´51´N, 116°36´42´´O; activated sludge and disinfection with chlorine), Sauzal (31°53´06´´N, 116°41´074´´O; activated sludge and disinfection with chlorine) and Naranjo (31°48´36´´N, 116°34´31´´O; activated sludge, rapid filtration with sand and anthracite and disinfection with chlorine). In the last one, samples were taken from a discharge located in Maneadero. In addition, a water sample was taken from the Emilio López Zamora Dam (ELZ) (31.88° N, 116.60° W) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Treatment plants of sewage and Emilio López Zamora dam at Ensenada, Baja California city: 1, ELZ dam; 2, The Northeast; 3, Sauzal; 4, Naranjo; 5, Gallo.

The samples were transferred to the laboratory in the Faculty of Sciences-UABC, kept in cold 8-10°C, to be processed in no more than 6 h. For the recovery of G. lamblia, 3.78 L of each sample were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min (SORVALL centrifuge, model: RC-5C PLUS). Subsequently, the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was washed twice with sterile distilled water and sterile saline phosphate buffer (PBS; NaCl 0.130 M, Na2HPO4 0.005 M, KHPO4 0.001 M, pH 7.4) and centrifuged as above. The resulting pellet was homogenized in 100μL of PBS and stored at -20ºC until subsequent use.

For the detection of Giardia cysts, the commercial direct fluorescent antigen assay kit (IVD Research INC®) was used, which provides all the reagents and materials. 10μL of the pellet of each sample, previously thawed, was taken, placed on slides, and dehydrated for 30 min in an incubator (MRC®) at 37ºC. Once dry, the samples were proceeded according to the methodology of the commercial brand. Finally, a drop of the preservative was added and immediately moved to its observation and quantification in an epifluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS BX61 motorized system) at 40 X with an excitation of 490-500nm and with a filter of 510-530nm. Each sample was analyzed by duplicate. The most probable number of total (CT) and fecal coliforms (CF) was used. The methodology is established in the Mexican standard (NMX-AA-042-SCFI-2015).

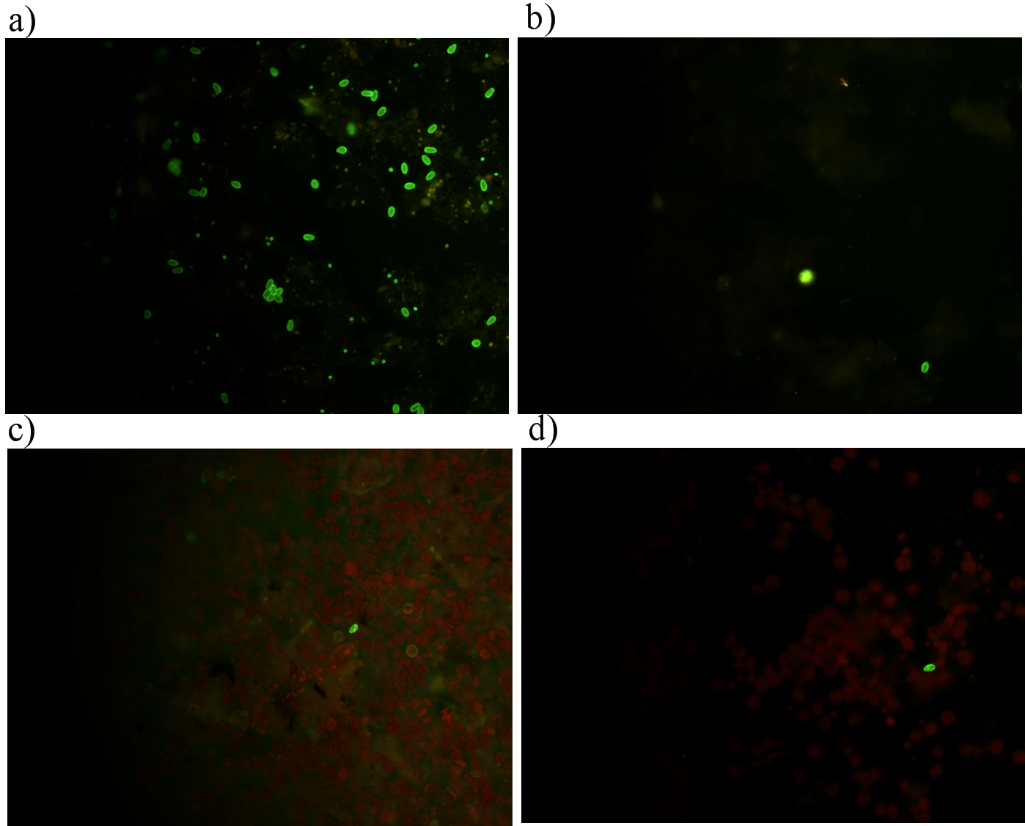

G. lamblia cysts were observed in the effluents from the wastewater of Gallo, Sauzal, and Naranjo (Figure 2). The higher number of cysts occurred at Gallo in September (280· L-1), while the lowest was observed in November (80· L-1). Naranjo has the highest in july (360· L-1) and the lowest in November (0· L-1). For Sauzal, the number of cysts fluctuated during the sampling months, being July the month with the highest concentration (240· L-1). There were no Giardia cysts throughout the study in the case of The Northeast and the ELZ dam.

Figure 2 Detection of G. lamblia by DFA by epifluorescence microscopy at 40X; a) positive control, b) El Gallo, c) El Sauzal, d) El Naranjo. 40X.

The quantification of G. lamblia cysts in the effluents studied ranged from 0 to 280 cysts/L for effluents with secondary treatment by activated sludge (Gallo and Sauzal) and from 0 to 360 cysts/L in the tertiary treatment effluent by rapid filtration by sand and anthracite (Naranjo) (Figure 3a). The coliforms (TC and FC) in the water of the Gallo were below 11 MPN/100 mL. In Sauzal, TC values reached up to 1600 MPN/100 mL in July, while FC values were below 240 MPN/100 mL. Naranjo has been found coliforms all months, being September the higher with more than 1800 MPN/100 mL of FC. The effluent from the Northeast had minimum values. However, October presented TC of 920 MPN/100 mL, while the other months were below 5 MPN/100 mL for TC and FC (Figure 3b, c).

Previous studies of Giardia in effluents from treatment plants in Canada, Spain, and Italy determined that the highest average concentration of cysts was in late summer and the lowest concentrations in winter,9 similar to this study. The number of cysts in this study ranges from 0–360 as Brazil of 2-898 cysts/L and Africa of 100-240 cysts/L.10-12 However, the results obtained in the effluent of Naranjo were higher than those obtained in Israel,9 where the same tertiary treatment was used, getting them from 0-8 cysts/L and this study 0-360 cysts/L. The reported values vary greatly; perhaps it may be due to the kind of treatment, plant conditions, the number of inhabitants to contribute to the volume of sewage, type of locality, physicochemical parameters, among others (Table 1).13

|

Place |

Treatment |

Giardia (cyst/L) |

Reference |

|

China |

Secondary/sand filter |

0 - 32 / 2.1 |

32 |

|

China |

Activated sludge/sand filter |

22 / 0 - 4 |

33 |

|

Canada |

Aerobic |

0.18 - 7.5 |

34 |

|

South Africa |

Secondary |

0 - 35 |

35 |

|

France |

Stability pond |

0 - 30 |

36 |

|

Malaysia |

Secondary |

1 - 500 |

37 |

|

USA |

Activated sludge/sand filter |

2300 / 18 |

38 |

|

USA |

Wetlands |

0.5 - 2.9 |

15 |

|

Ireland |

Wetlands |

11 - 111 |

16 |

|

Scotland |

Activated sludge/biological filter |

354.3 / 40 |

39 |

|

Italy |

Ultra filtration |

0 |

17 |

|

Brazil |

Activated sludge |

1100 |

40 |

|

Spain |

Stability pond |

0 - 5.3 |

41 |

|

China |

Secondary |

1187 |

42 |

|

México |

Activated sludge |

0 - 240 |

This study; Sauzal |

|

México |

Activated sludge |

0 |

This study; The Northest |

|

México |

Activated sludge |

48 - 280 |

This study; Gallo |

|

México |

Activated sludge and sand-anthracite filter |

0 - 360 |

This study; Naranjo |

|

México |

|

0 |

This study; ELZ dam |

Table 1 Giardia lamblia detected by DFA in sewage

Comparative studies of removal rates in treatment plants have found that higher rates are in those who use secondary treatments based on oxidation ditch and the anaerobic-anoxic-aerobic process than activated sludge; the last is used in Ensenada treatment plants. Other studies pointed out that tertiary treatments in ponds and lagoons help with cyst removal; however, this treatment depends on the available land.14 Although in the USA was reported 0.5–2.9 and Ireland 11-111 cyst L-1 using the wetland.15,16 In Italy was reported zero cysts using ultrafiltration; maybe this kind of treatment will be the best for Giardia cyst removal.17

The US Environmental Protection Agency points out that there is no correlation between the concentration of fecal coliforms and G. lamblia cysts; they also report that the amount of this parasite in untreated drainage waters ranges from 10,000 to 100,000 cysts/L, while in treated waters, it ranges from 10 to 100 cysts/L and ten cysts or less in surface water or hood piped water.18 However, Coupe et al. relate the presence of Giardia cysts with fecal coliforms and enterococci. In this work, no relationship was observed between them.19

It is important to say that the effluents from the treatment plants in this study discharge into the ocean of Todos Santos Bay. G. lamblia has been reported in seawater and marine organisms and is related higher incidence of the parasite where wastewater is discharged.20-22 On the other hand, a higher number of gastrointestinal infections has been observed in bathers who go to contaminated coastal areas.23,24 Although this study did not contemplate the survey in the seawater surrounding the sewage effluents, the presence of Giardia will be analyzed in the future since it represents a public risk.

The low concentrations of FC recorded in sewage effluents during June-November 2019 suggest that wastewater treatment removes a high FC concentration since it is assumed that the plant receives high concentrations of FC from domestic drains. On the other hand, most samples (97%) meet the parameters of the official Mexican standards for the discharge of wastewater into national waters and goods according to the official Mexican standard (NOM-001-SEMARNAT-1996), where FC values are less than 2,000 NMP/100 mL and are considered acceptable. However, NOM-003-SEMARNAT-1997 establishes that water for public services with direct contact must have a maximum FC of 240 NMP/100 mL, and for indirect or occasional contact, the maximum limit is 1,000 NMP/100 mL.

It is important to note that an exception was the ELZ dam, where FC was found, this is possibly due to leaks from homes that are near this area or to natural runoff with fecal matter from animals, like what was found in the Cacao dams in Cuba and San Rafael in Nayarit, Mexico.24-26 The results of this study are like those found by González-Moreno27 in the effluents of Gallo and Naranjo plants. It is important to note that the water coming from Naranjo and collected in dam 97 showed in September FC values higher than 1800 NMP/100 mL, this water is used for agriculture, so it is necessary to evaluate the microbial content before use to avoid infections.

According to Mendoza-Espinosa et al.28, high coliform values in some sampling stations may be caused by inadequate chlorination. Metcalf & Eddy29 mention that the lack of quality in a treatment plant that leads to non-compliance with the different regulations may be due to problems caused by mechanical failures such as design errors and operational failures, and the changing characteristics of the wastewater. On the other hand, it is essential to note that the sewage from Sauzal, The Northeast, and Gallo flow into the ocean, where the public performs recreational activities, and they are exposed to high concentrations of bacteria and parasites. Although it has been pointed out that seawater affects the survival of E. coli (the primary bacterium that constitutes the population of fecal coliforms), some studies indicate the viable form of this species in the ocean.30,31

In conclusion, this study demonstrated G. duodenalis in effluents from treatment plants in Ensenada, Baja, California; their presence represents a risk to public health since they are discharged in the coastal area with recreational activities population.

We thank CONACyT for their financial support No. C0011-CONACYT-CDTI-188920.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

©2021 Portillo-López, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.