Journal of

eISSN: 2376-0060

Case Report Volume 8 Issue 1

1Pneumology “C” Department, Abderrahman Mami Hospital, Tunisia

2Department of Immunology, Abderrahman Mami Hospital, Tunisia

3Research Laboratory “Analysis of the Effects of Environmental and Climate Change on Health”, Department of Epidemiology and Statistics, Abderrahmen Mami Hospital, Tunisia

4Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, Tunis El Manar University, Tunis, Tunisia

Correspondence: Amani Ben Mansour, Pneumology “C” Department, Mami Ariana Hospital, Medical faculty of Tunis, Tunisia

Received: November 23, 2020 | Published: February 22, 2021

Citation: Mansour AB, Saad SB, Yaalaoui S, et al. Antisynthetase Syndrome associated with mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, presenting as an acute respiratory failure. J Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2021;8(1):13-15 DOI: 10.15406/jlprr.2021.08.00243

Antisynthetase syndrome (ASS) is characterized by myositis, interstitial lung disease, Raynaud’s phenomenon, fever and mechanics hands. Diagnosis is confirmed with the detection of an antibody directed against anti–aminoacyl–transfer–RNA synthetases (ARS). The most common anti–ARS antibody is anti–Jo–1. Opportunistic infections are common causes of mortality in patients with autoimmune diseases. Immunosuppressive treatment further contributes to the risk of infection.

We report a rare case of a 68 year–old man diagnosed with antisynthetase syndrome associated to a pulmonary tuberculosis infection, revealed with an acute respiratory failure. The diagnosis of this rare combination of a connective tissue disease and tuberculosis revealed with an acute respiratory failure is difficult in a previously asymptomatic patient. Early diagnosis and immunosuppressive therapy associated to antituberculosis treatment started precociously prevented the disease progression and resulted in a good outcome.

Keywords: anti–synthetase syndrome, respiratory failure, interstitial lung disease, tuberculosis, mycobacterium tuberculosis

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies are rare autoimmune diseases characterized by proximal muscle weakness in association with various clinical involvements of the joints, skin, lungs, and esophagus.1 One subset, antisynthetase syndrome, requires an antibody directed against aminoacyl transfer RNA. Pulmonary tuberculosis in autoimmune conditions is may be accredited to various immune irregularities as well as to treatment with immunosuppressive therapy. Herein, we report a 68–year–old man who presents with fever and acute respiratory failure, who was diagnosed with anti–JO1 antibody associated antisynthetase syndrome. Associated pulmonary tuberculosis was secondary identified.

A 68 year–old man, builder, with non-smoking history was admitted to the pulmonology department for acute dyspnea, weakness and fever, with rapid deterioration of respiratory conditions. He has a history of erysipelas of the lower limb 10 years ago, single kidney (organ donation for his daughter in 2018) and newly diagnosed diabetes. He did not report any other symptoms and had been in good health until the last 4 weeks. The physical examination revealed the following: body temperature 37.8°C, respiratory rate 24breaths/minute, blood pressure 150/75 mmHg, pulse rate 107beats/minute, and oxygen saturation 81% on room air. Fine crackles were heard at the base of the lungs. A rough appearance of the hands was noted (Figure 1). Skin exam was negative for rash. There was no lymphadenopathy. The rest of the exam was normal.

Figure 1 Fissural and erythematous hyperkeratosis of the palmar face of the hands (mechanic's hands).

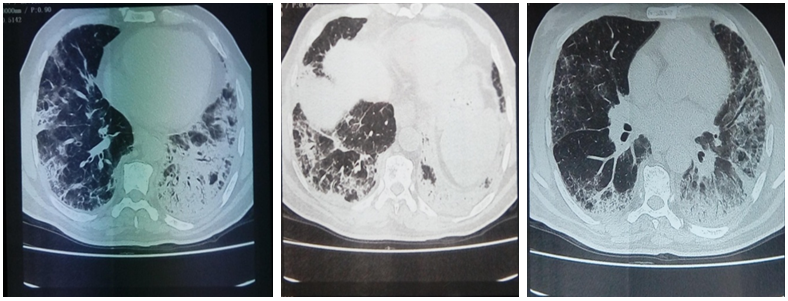

At admission, the patient had acute respiratory failure. Arterial blood gas analysis with oxygen 8 L/min showed a PaO2 of 67 mmHg, PaCO of 31 mmHg, pH of 7.47, and HCO3 of 23mEq/L. A thoracic radiograph showed multiple pulmonary infiltrates consistent with interstitial lung disease (Figure 2). Echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular function. Laboratory investigations revealed neutrophilic leukocytosis (white blood cells 14200/UL, neutrophils 11640/mL, lymphocytes 1670/mL); elevated sedimentation rate 136 (<20 mm/h); elevated lactated shydrogenase (LDH),313 U/L; creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level,24 U/L (0–195 U/L) aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level, 15 U/L (6–34 U/L); alanine transaminase (ALT) level, 16 (6–34 U/L); and C–reactive protein, 44 mg/dL (0–5 mg/dL). HIV test was negative.

He was diagnosed with severe community–acquired pneumonia and treated with oxygen, intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics (amoxicillin– clavulanic acid and Erythromycin).

High–resolution computed tomography of the chest showed bilateral micronodular opacities, thickening of septal lines, traction–bronchiectasis, all consistent with bilateral interstitial non-specific pneumonia (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Chest High–resolution computed tomography showing bilateral micronodular opacities, thickening of septal lines, traction–bronchiectasis, all consistent with bilateral interstitial nonspecific pneumonia.

On the third day of hospitalization, the patient’s general and respiratory conditions worsened. Atypical bacterial pathogens serologies was negative as well as RT–PCR influenza A (H1N1), negative cytobacteriological examination of sputum and negative mycobacterium tuberculosis sputum.

Since there was no evidence of bacterial, fungal, or viral infection, we suspected inflammatory myopathy with interstitial lung disease.

Thus, we checked specific markers for connective tissue diseases. Laboratory immunological tests revealed increased anti–nuclear antigen antibodies, as well as positive anti–extractable nuclear antigen (anti–Jo–1 antibodies positive and anti–SSA–Ro52 positive); rheumatoid factor and anti–neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (C–ANCA and P–ANCA) were at normal values. Bronchoalveolar lavage was not performed initially. The diagnosis of Antisynthetase syndrom was made, and the patient continued prednisone at the dose of 60mg/day (1mg/kg). Cyclophosphamide pulse therapy (750mg. once every 45 days × 6) was programmed.

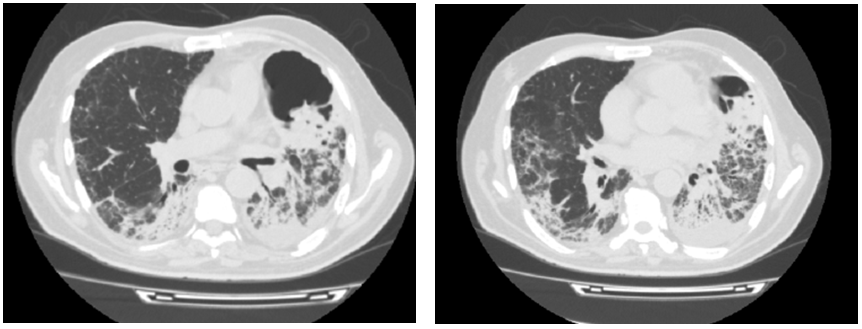

In the workup before beginning immunosuppressive treatment, a thoraco–abdomino–pelvic tomography was performed. In addition to interstitial lung disease lesions, mediastinal and hilar adenomegaly, lingular excavated lesion and confluent centrilobular micronodules of the left lung was noted (Figure 4). Rapid multiplex–PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis diagnosis using sputum samples was positive. The diagnosis of associated pulmonary tuberculosis was retained.

Figure 4 Chest High–resolution computed tomography showing lingular excavated lesion and confluent centrilobular micronodules of the left lung.

In addition to corticoids treatments, anti–tuberculosis drug has been started (Isoniazid 300mg/j, Rifampicin 600mg/j, Pyrazinamid 1600mg/j, Ethambutol 1100mg/j).

Three weeks after the begining of anti–tuberculosis treatment, the respiratory effort had improved, and the patient was discharged. At short–term follow–up, he reported significant improvement in his dyspnea. Patient’s respiratory condition improved (PaO2 82.9 mmHg, PaCO 33.5 mmHg, pH 7.46, and HCO32 24 mEq/L on 3 l/mn oxygen );and laboratory values for blood cell count, CPK, LDH, and CRP returned to normal ranges within three weeks.

The diagnosis of polymyositis/ dermatomyositis PM/DM–related to interstitial lung disease (ILD) is not difficult in patients with established disease or in newly diagnosed patients with typical disease manifestations.2 However, PM/DM may not be suspected to be the cause of ILD when ILD is the only manifestation.3 Severe respiratory failure as the presenting feature of ILD associated with ASS is extremely rare. Acute respiratory failure is an extremely rare presentation of the ASS syndrome.2 Clinical suspicion of polymyositis is high where muscle pain or tenderness is obvious, but these symptoms are present only in 50% of the cases.4 Antibodies are directed against aminoacyl transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetases. Eight antibodies have been discovered, including anti–Jo–1 (most common), anti–EJ, anti–PL7, anti–PL12, anti–OJ, anti–KS, anti–ZO, and anti–Ha.5 Nearly all are associated with ILD, but myositis is closely associated with Anti–Jo–1, Anti–PL–7, and Anti–EJ.6 Patients with non–Jo–1 antibodies are shown to have lower survival rates.7 Corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of initial empiric treatment for inflammatory myopathy.8 Among patients with antisynthetase syndrome–related ILD, the response to therapy with prednisone is heterogeneous, with 30–40% of the subjects showing improvement and 20–40% being stabilized.9,10 Other immunosuppressive drugs should be considered at the outset of treatment, particularly in ASS and other severe and progressive manifestations of ILD.11 For patients who have responded poorly to the conventional pulse steroid therapy, increasing the intensity of pulse cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, or other immunosuppressive therapy earlier remain the best approach.12

Individuals with systemic connective tissue diseases are at increased risk for developing infection, either from immune abnormalities, from the disease itself, or from immunosuppressive treatment. Bacterial infections are most common, but viral and fungal infections also contributed to increased morbidity and mortality.13

A study of eighteen patients with PM/DM showed a high frequency of opportunistic infections, with more than 50% being fungal.14 The incidence rate of M.tuberculosis infection in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies is greater than the incidence in the general population.15 Extrapulmonary patterns of tuberculosis have also been described to be more common in IIMs; in a retrospective case series of thirty patients who had tuberculosis and systemic rheumatic disease, 2/3 of the patients had extrapulmonary tuberculosis while only 1/3 had pulmonary tuberculosis.16 It is possible that the immunosuppression in our patient led to re–activation of tuberculosis.

This case illustrates an extremely rare association in the medical literature between anti–synthetase syndrome and mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment lead to better prognosis.

There are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2021 Mansour, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.