Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 1

1Dental School, Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil

2Dental School, Brazilian University Centre, Brazil

3Department of Prosthodontics and Oral Facial Surgery, Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil

Correspondence: Fabio Barbosa de Souza, Federal University of Pernambuco, Department of Prosthodontics and Oral Facial Surgery, Av. Prof. Moraes Rego s/n, Cidade Universitÿria, RecifePE, CEP: 50670-901, Brazil

Received: January 10, 2019 | Published: January 17, 2019

Citation: Vieira EG, Donida FA, Souza FB. Dental urgencies in a brazilian dental school: a cross-sectional study. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2019;10(1):35-39. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2019.10.00456

At the Federal University of Pernambuco - Brazil, care of dental urgencies is held in the Reception and Care Center (RCC) of the Dental School. This study aimed to evaluate the epidemiological profile and treatments performed in urgency room visits in the RCC and the social profile of patients arriving. An observational descriptive study was conducted to evaluate the physical medical records of patients treated in the period of one year. The data was performed were organized in electronic spreadsheets and submitted to descriptive and inferential statistics, with the significance level of 5%. The main problem was the pain (70%); the most predominant diagnosis was pulpitis (41%); the treatment was performed over the opening sequence, the within the duct medication and temporary restoration of the crown (50,5%). Most patients are women (66,9%), from Recife (54,1%) and adulthood (76,9%). It was concludedrgencye that because most of the complaints are of pulp origin, RCC should prepare to serve mainly endodontic emergencies.

Keywords: dentistry, dental urgencies, epidemiology

Dentistry, over the years, has presented significant changes in its profile of care to the population, mainly within the social strata that depend on public or philanthropic assistance. This is because the dentist has always been considered a health profession that had a model of assistance that was markedly mutilating, and which is moving towards a model based on acceptance, respect and integrality.1 The maturation of these issues and the need to improve the epidemiological indices of oral health of the Brazilian population, as well as access to services, led the Federal Government to launch, in 2004, the National Oral Health Policy Guidelines.2

The reorientation of the model of care in oral health involves comprehensiveness, resolution and qualification of primary care, inseparably linked to the service network as a whole.3 Considering this rhizomatic nature of oral health care to be offered to the population, higher education institutions with dental school clinics should also be constituted as places to provide services, which must be articulated with the other points of care, based on flows of reference and counter-reference. At the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), the dental school is structured based on this line of reasoning, offering care aimed at basic and specialized care, as well as through the resolution of urgent situations.

In Brazil, a country with high unemployment, low per capita income and health indicators at alarming levels, the majority of the population depends on the public health system. However, it does not yet have a sufficient structure to adequately meet all the demand, thus generating a large influx of patients to urgency services.4 Therefore, it is important to emphasize that, even with the current advances in Dentistry and the emphasis on prevention programs, due to the lack of information and financial resources, the patient's demand for urgent care is, in most cases, motivated by a complaint of pain being caused mostly by caries and its sequelae.4 The greatest demand for dental urgency services is due to pulp and periapical disease, with pain being the most relevant symptom. Demand also occurs due to hemorrhage, functional loss or post-surgical complications.5,6 In addition, in an urgency situation, it is important to remember that anxiety is intense and involves emotional contents of all present. Therefore, in the face of such an occurrence, the important thing is to go to the place of care with tranquility, without hurry and relieve tensions, identifying the existing problem.1 Thus, in addition to the patient's complaint, the professional should analyze the whole stomatognathic system in order to identify other lesions in an early form.2

At UFPE, urgency services are performed at the Reception and Care Center (RCC). In this space, service in addition to attending urgency cases, is the patient's doorway to the services of attendance at the Dental School, performing the reception, opening of the single medical record, screening and referral of patients to the school clinics. Therefore, analyzing the profile of dental urgency care performed at RCC is fundamental for the knowledge about the degree of resolution of users' demands, as well as for planning actions aimed at improving the service. The objective of this study was to evaluate the epidemiological profile and treatments performed in urgency room visits at the RCC of the UFPE Dental School and the social profile of the patients received in one year of care.

A descriptive observational study was performed to evaluate the physical charts of the patients attended at the RCC Dental School of UFPE. This project was submitted and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the UFPE (CAAE 43686515.2.0000.5208). The research was performed in the RCC itself after obtaining consent issued by the institution. From the physical archive of the RCC, 399 medical records of users who sought the service to perform urgency were analyzed in a period of one year. Through a data collection form, a single operator performed the transcription of the research information, which had as variables: age, sex, city of residence, main complaint, diagnosis and treatment performed. The data were organized in electronic spreadsheets and submitted to descriptive and inferential statistics, with a significance level of 5%. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 13.0) and Excel 2010, both for Windows, were used to obtain the statistical data. All tests were applied with 95% confidence.

A total of 399 medical records of patients attended by the urgency department of the RCC-UFPE in a one-year period were evaluated. There were 218 calls in the first half and 181 in the second. Initially it was verified that there was a greater demand for the service by female subjects, being they responsible for 66.9% of the attendances. Only a third of the patients were male. The number of attendances distributed by sex in each semester can be observed in Figure 1.

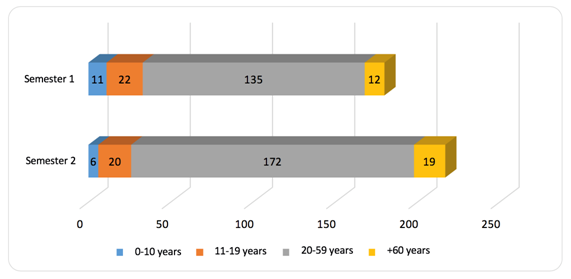

For the evaluation of the age, the patients were divided into four age groups corresponding to the age groups used for classification and screening of patients attending the full dental clinics at the UFPE Dental School, from 0 to 10 years old, from 11 to 19 years old, from 20 to 59 years and 60 years or more. There was a predominance of visits to patients in the age range between 20 and 59 years in two semesters. Detailed data can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Profile of users submitted to RCC urgencies regarding age in each semester, in absolute values.

The patients' place of residence was also analyzed. The great majority came from the city of Recife in both periods studied. Detailed data about this variable are shown in Figure 3.

Among the motivating complaints for the search of the urgency service, the pain was highlighted with 70% of the total reports. The other complaints are detailed in Table 1. The diagnoses were the most varied, with emphasis on pulpitis, pulp necrosis and extensive caries in both periods studied. Regarding the care offered by the service, predominance was based on the sequence-based treatment: coronary opening, intracanal medication and temporary restoration; followed by treatment based only on temporary restoration. The information regarding the diagnoses and the treatments performed are shown in Table 2.

|

Semesters |

|||

Variables |

Total n (%) |

1 n (%) |

2 n (%) |

p-value |

Main Complaint |

|

|

|

|

Pain |

278 (70,0) |

158 (73,1) |

120 (66,3) |

0,105* |

Dento-alveolar trauma |

18 (4,5) |

5 (2,3) |

13 (7,2) |

|

Restoration fracture |

32 (8,1) |

16 (7,4) |

16 (8,8) |

|

Provisional Restore Failure |

13 (3,3) |

9 (4,2) |

4 (2,2) |

|

Other complaints |

56 (14,1) |

28 (13,0) |

28 (15,5) |

|

Uninformed |

2 (0,5) |

¥ |

¥ |

|

Table 1 Distribution in absolute and relative values of the main complaints reported by the users who used the urgency service

(*) Chi-square test (¥) Do not enter the comparison

The profile of the population assisted by the urgency department of the RCC-UFPE, in the year studied, showed a tendency to attend to female patients who were maintained in the two semesters; 65.6% and 68.5%. The state of Pernambuco has a population composed mostly of women,7 a fact that may explain why the predominance of female patients in the urgent care of the RCC-UFPE. Another factor is that women are usually responsible for accompanying children and the elderly to health services, which can generate a greater motivation to seek care.4 In a similar study, Sanchez and Drumond1 reported similar findings. They point to the cultural or social issue as one of the factors of women's greater demand for health services.

In this study, the age groups were organized in a similar way to those used by the dental clinics of UFPE. A predominance was observed in the visits to adults (20 to 59 years) in the two periods studied, in agreement with the data found in other studies.1,6,8,9,10 As the age group advanced, there was a continuous decrease in the number of users in the urgency department. It is hypothesized that the smallest number of people over 51 years of age is due to the population contingent being formed by partially edentulous people. Therefore, they are less likely to seek urgency dental care due to dental problems. The investigation performed by Da Fonseca et al.11 showed that the age group with the largest search for urgency service was between 20 and 49 years. These results coincide with the research carried out in educational institutions and with the few studies carried out in the country's first-aid and health units.8,9,11

The majority of the patients come from the city of Recife and the Metropolitan Region of Recife (MRR), as shown in graph 3. However, it is not possible to determine if the search for the service in the UFPE was due to the reliability of the service or if it was due to the difficulty of service within the municipal and state health services. Further studies should be performed to define the motivating agent. But considering the distance traveled by individuals from MRR cities and elsewhere, service users probably did not have access to the health care service in their city.¹ In addition, the trip to the service could have been motivated by the possibility of access to a more specialized care.12

The complaint of pain was the main motivator for the search of the dental urgency service of the RCC/UFPE, reporting 73.1% of those treated in the first semester and 66.3% of those seen in the second semester. This result may reveal shortcomings in the primary care service of the region, which is not capable of promoting oral health. Pain is also reported as the main complaint in several studies similar to this.1,4−6,8,10,13−16 Other complaints obtained a total of 14.1%. In this group, complaints of lower value or others that did not show direct reference to urgency were grouped. For children, on the other hand, trauma and toothache constituted the most common reasons for dental emergency visits at a hospital emergency center in Taiwan.16

Most of the complaints had pulp origin due to pulpitis (41%) or pulp necrosis (15.6%) (Table 2). Other complaints appear in lesser proportion and are revealed from other sources such as fracture restoration and fractured teeth with 4.5% and 3.3%, respectively. Some diagnoses do not have their own urgency characteristics; however, they can lead to an urgency situation depending on their state and severity. This is especially true if they are causing pain to the patient, as in the case of aggressive periodontitis and furcation. It is important to note that the furcation lesion does not only have periodontal origin; may also result from iatrogenic perforation. Faced with such a large number of different diagnoses, it is important to highlight that the diseases that involve the dental elements can be several and occupy different stages of evolution. Therefore, correct diagnosis is essential for effective treatment.4 Extensive caries appeared in 11.4% of the medical records as a diagnosis (Table 2). However, other diagnosed pathologies originate from caries, revealing the high rate of involvement by this pathology of the patients treated.

|

|

Semesters |

|

|

Variables |

Total |

1 |

2 |

p-value |

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

Diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

Pulpitis |

163 (41,0) |

97 (45,3) |

66 (36,4) |

0,024** |

Acute periapical abscess |

20 (5,0) |

5 (2,3) |

15 (8,2) |

|

Pulp necrosis |

62 (15,6) |

34 (15,4) |

28 (15,4) |

|

Tooth fracture |

13 (3,3) |

7 (3,2) |

6 (3,3) |

|

Provisional Restore Failure |

2 (0,5) |

0 (0,0) |

2 (1,1) |

|

Fistula |

1 (0,3) |

1 (0,5) |

0 (0,0) |

|

Extensive caries |

45 (11,4) |

20 (9,0) |

25 (13,7) |

|

Restoration fracture |

18 (4,5) |

9 (3,9) |

9 (4,9) |

|

Hypersensitivity to dentin |

11 (2,8) |

10 (4,4) |

1 (0,6) |

|

Periodontal Abscess |

6 (1,5) |

5 (2,3) |

1 (0,6) |

|

Pericoronitis |

3 (0,8) |

0 (0,0) |

3 (1,7) |

|

Provisory failure (prosthesis) |

8 (2,0) |

5 (2,3) |

3 (1,7) |

|

Root remainders |

2 (0,5) |

1 (0,5) |

1 (0,6) |

|

Alveolar osteitis |

1 (0,3) |

0 (0,0) |

1 (0,6) |

|

Occlusal trauma |

3 (0,8) |

1 (0,5) |

2 (1,1) |

|

Temporomandibular disorders |

5 (1,3) |

4 (1,8) |

1 (0,6) |

|

Aggressive Periodontitis |

9 (2,3) |

6 (2,6) |

3 (1,7) |

|

Deciduous tooth exfoliation |

5 (1,3) |

3 (1,4) |

2 (1,1) |

|

Neuralgias |

2 (0,5) |

2 (0,9) |

0 (0,0) |

|

Furcation lesion |

2 (0,5) |

2 (0,9) |

3 (1,7) |

|

Acute apical periodontitis |

9 (2,3) |

3 (1,4) |

6 (3,3) |

|

Undetermined diagnosis |

6 (1,5) |

3 (1,4) |

3 (1,7) |

|

Treatment performed |

|

|

|

|

Prosthesis cementation |

11 (2,8) |

6 (2,8) |

5 (2,8) |

0,717** |

Abscess Drainage |

6 (1,5) |

3 (1,4) |

3 (1,7) |

|

Temporary restoration |

80 (20,1) |

46 (21,1) |

34 (18,8) |

|

Definitive Restoration |

18 (4,5) |

7 (3,2) |

11 (6,1) |

|

Coronary opening + Intra-anal medication + temporary restoration |

202 (50,5) |

115 (52,7) |

87 (48,0) |

|

Intra-anal medication + temporary restoration |

22 (5,5) |

14 (6,4) |

8 (4,4) |

|

Dental extraction |

31 (7,8) |

13 (6,0) |

18 (9,9) |

|

Occlusal adjustment |

4 (1,0) |

2 (0,9) |

2 (1,1) |

|

Prescription drugs |

10 (2,5) |

4 (1,8) |

6 (3,3) |

|

Others |

15 (3,8) |

8 (3,7) |

7 (3,9) |

|

Table 2 Distribution of absolute and relative values of diagnoses and treatments performed in the urgency department

(**) Fisher's Exact Test

Coherently to the previously reported data,6,8,10 the treatment sequence of coronary opening - intracanal medication-temporary restoration was the most commonly treatment performed, followed by the procedure to control diseases of endodontic origin. In a previous study performed also in the UFPE urgency dental care service between 2004 and 2005, a similar result was described, maintaining the same trend of procedures in this service.8

The population attended in the urgency department of dental school was predominantly adult and female, whose most common complaint was pain, resulting mainly in diagnoses and treatments of endodontic origin. From this perspective, the urgency health care service must move its efforts toward equipping itself with materials needed for this type of approach, as well as enabling students to perform urgency endodontic therapy procedures.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2019 Vieira, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.