Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

This paper documents a rare case of a secondary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) at the right maxillary alveolar ridge in a 70-year old male patient. The patient complained of severe pain. His medical history revealed a poorly differentiated SCC in his left maxillary sinus totally excised 20 years ago. Left maxillary sinus was normal at the time of examination, but the right maxillary sinus was completely involved. Total excisions of the lesion and neck dissection were performed for the patient and he was referred to an oncologist for further investigation and treatment. General dentists must be able to correctly diagnose the presence of any dysplastic, premalignant or malignant lesion in the oral cavity and refer the patients to an oral medicine specialist and/or oral and maxillofacial surgeon for a thorough diagnostic workup and treatment planning.

Keywords: neoplasms, second primary, carcinoma, squamous cell, pain

SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; RB, retino blastoma; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HPV, human papilloma virus; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SEER, surveillance epidemiology end result

Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for over 95% of the carcinomas of the oral cavity. It is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality especially in developing countries. In comparison with other malignancies, SCC has a relatively low survival rate (50%). According to a report by the World Health Organization, carcinomas of the oral cavity rank the sixth and tenth most common cancers in males and females, respectively in developing countries.1

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) has a high incidence rate (3%). Lifestyle risk factors predisposing patients to OSCC include tobacco use, alcohol consumption and betel chewing. Role of genetics in development of OSCC has also been documented but its exact mechanism is not clear. Environmental factors may play a role in this regard as well. Occurrence of OSCC includes a gradual evolution from normal epithelium through transitional precursor states to a full-blown metastasis. Such genetic alterations will result in phenotypic changes appearing as potentially malignant oral lesions. Several genes are believed to play a key role in carcinogenesis, particularly the tumor suppressor genes such as the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, TP53 and retinoblastoma RB1 as well as oncogenes such as the cyclin family, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and ras oncogene. Tumorigenic effects of some viral infections, especially with the oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) subtypes, have also been documented particularly in oropharyngeal cancer.2-7

This paper documents a rare case of a male patient with secondary SCC.

A 70-year-old Iranian male patient (Figure 1) was referred by his dentist to Shahid Beheshti Dental School because of an exophytic ulcerated lesion on his right maxillary alveolar ridge. Although the patient was generally healthy, his medical history revealed excisional biopsy of a SCC in his left maxillary sinus 20 years ago. His family history was unremarkable. He was a nonsmoker and did not report alcohol use although he was using opium for pain relief since he was suffering from severe pain. He underwent full ear, nose and throat workup, but nothing was found in his left sinus. The patient was then referred to the Oral Medicine Department of Shahid Beheshti Dental School for further investigations. He had a large swelling on the right side of his face causing facial asymmetry. He did not report any obstruction or epistaxis. Palpation of his maxillary sinuses was also normal. Two submandibular lymph nodes were palpable at the time of examination; they were non-tender, firm and fixed to the adjacent tissues. Intraoral clinical examination showed an exophytic lesion on the maxillary alveolar ridge extending from the anterior part to the tuberosity and from the buccal vestibule to the midline of the palate at the right side of the maxilla (Figure 2 & Figure 3). Surface of the lesion was ulcerated and covered with a fibrino leukocyte membrane. The lesion had a firm consistency and it was tender on examination. Panoramic radiograph showed no sinus involvement at the time of examination (Figure 4). The patient was aware of the possibility of malignancy and did not report similar conditions in his relatives. He was symptomatic and complained of acute recurrent pain at the site of lesion extending to his right face. He was referred to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Shahid Beheshti Dental School with a possible diagnosis of secondary SCC. Cardiovascular and pulmonary examinations were normal (Figure 5). Axial computed tomography (CT) and coronal T1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were ordered for the patient one day before the surgery, which showed a soft tissue mass that had invaded and destructed the inferior and medial walls of the right sinus and the septum of the nose. It had also resulted in erosion of the inferior wall of the right orbit (Figures 6-8). TNM classification showed stage IV cancer.

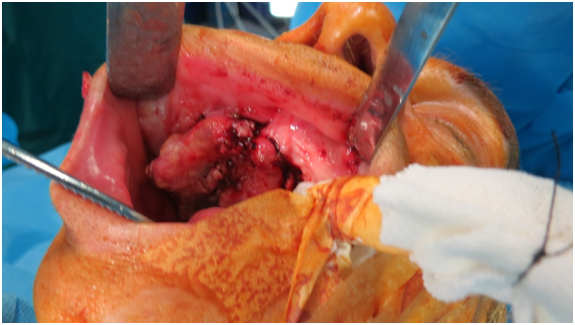

The lesion was totally excised and total maxillectomy and neck dissection was performed three weeks after the examination (Figure 9 & Figure 10) in order to prevent recurrence (Figures 11-13). Histopathological analysis revealed aplastic squamous cells in a desmoplastic stroma, with moderate eosinophilic pale to clear vacuolated cytoplasm with prominent eosinophilic nuclei and frequent mitosis indicative of poorly differentiated SCC. Keratin pearls and squamous whorls were also abundantly found. At some foci, spindling, tumor necrosis and ulceration were also noted, which further confirmed the diagnosis of SCC.

Figure 10 N=57; Epidemiological distribution of the pathological fractures, traumatic fractures, and nonunion.

Oral cancer is a public health dilemma. Aging and chronic diseases increase its incidence. The role of tobacco use and alcohol consumption in development of OSCC has been well documented. However, the etiology of OSCC patients with no history of drinking and/or smoking remains unknown. About 15 to 20% of patients with oral cancer do not have the traditional risk factors such as smoking or alcohol consumption. OSCC ranks the fifth most common cancer worldwide. A possible association between the HPV and OSCC has been suggested in the literature. Patients with no potential risk factors must be further evaluated to find a possible etiology. A high percentage of non-smokers, non-drinker female patients over 70 years old have been reported with smaller tumors sizes at non-lingual sites.8-10 Although our patient was male, he suffered from OSCC at the right side of the maxilla, which is in line with the results of the above-mentioned studies.

Approximately 1,529,000 new oral cancer cases are annually detected in the United States.11 However, despite the advances in surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, only about half the patients will survive for five years. A five-year survival rate of only 53% has been reported for African-Americans suffering from oral cancer. Such high mortality rate is mainly due to the advanced stages of cancer at the time of diagnosis and treatment. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute, at the time of diagnosis, over half the patients have late stage cancers (stages III and IV) already spread via the lymphatic system to the regional cervical lymph nodes. Moreover, all these malignancies have local invasion and a significant percentage of them metastasize hematologically.11 However, our patient was suffering from secondary OSCC and no other mass was found in his left sinus or anywhere else at the time of examination.

A multimodal surgical approach for the primary tumor and the neck is often preferred followed by postoperative radiotherapy/chemotherapy. This treatment option seems superior to non-surgical treatment protocols and often results in higher disease-free and overall survival rates.12,13 Our patient was surgically treated and underwent total maxillectomy and neck dissection). But, we did not schedule radiotherapy or chemotherapy for the patient since he had no metastasis.Although secondary OSCC is very rare, appropriate treatment planning is required to prevent metastasis or recurrence. Thus, general dentists must be able to correctly diagnose the presence of any dysplastic, premalignant or malignant lesion in the oral cavity and refer the patients to an oral medicine specialist or an oral and maxillofacial surgeon for further diagnostic workup and appropriate treatment planning.

The author declares that there was no conflict of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.