Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4396

Research Article Volume 12 Issue 3

1King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Science, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Cardiac Sciences, King Faisal Cardiac Center, Ministry of national Guard Health Affairs Jeddah 21423, Saudi Arabia

3King Abdullah international medical research center Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

4East Midlands Congenital Heart Centre Glenfield Hospital. University of Leicester NHS Hospitals Trust, United Kingdom

Correspondence: Saad Al Bugami, Department of Cardiac Science, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Science, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Tel 966505516952

Received: May 15, 2019 | Published: May 27, 2019

Citation: Bugami SA, Bashaweih R, Hijazi R, et al. Outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention among patients with coronary artery disease in Saudi Arabia. J Cardiol Curr Res. 2019;12(3):55-58. DOI: 10.15406/jccr.2019.12.00439

Background: There is no published risk score model to predict mortality and morbidity following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Saudi Arabia. We aim to identify risk predictors that can estimates risks associated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) specific to Saudi population that can be incorporated in creation of a population specific risk model.

Methods: Data of 418 patients who were treated with percutaneous coronary intervention at king faisal cardiac center (KFCC) were retrospectively collected from January 2015 till December 2017. Demographics and clinical data were measured to define clinical predictors associated with in hospital death and Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE).

Results: The study included 418 patients who underwent PCI between January 2015 until December 2018. The majority of the patients were of Saudi nationality (92.4%). The mean age was 60.58 (±7.8). Out of the study subjects, 225 (53.8%) were 60 years of age and above. Majority were male 315 (75.36%). The most prevalent pre-procedural risk factors were hypertension in 82%, Diabetes Mellitus in 74.52%, and dyslipidaemia in 70.7% of patients. Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction was the major presentation with a percentage of 58.39%. The PCI status among the patients was divided into 38.35% urgent PCI, 35.19% elective PCI, and 26.46% primary PCI. In-hospital mortality occurred in a total of 5 patients (1.2%). Nineteen patients (4.5 %) experienced post-procedural complications. Intra procedural cardiac arrest occurred in 5 patients (1.2%). four patients (0.96%) required blood transfusion three of them due to post procedure bleeding. Other procedure related complications were as follows, cardiac tamponade (0.49%), stroke (0.73%), contrast allergy (0.24%), contrast nephropathy (0.73%), new requirement for dialysis (0.49%), and death in Cath lab (0.24%). Dyslipidaemia, previous renal disease, PCI indication, cardiogenic shock, pre and post-procedural haemoglobin level as well as post-procedural creatinine level showed significate relationship with in hospital MACE.

Conclusion: Our findings suggest favourable outcomes of patients treated with PCI, matching the international data. We have identified certain risk predictors that need to be confirmed by large scale and prospective data In order to generate a population specific risk score model.

Keywords: complications, Coronary artery disease, Outcome, Risk, myocardial infarction, include, gender, diabetes, cardiogenic shock, previous MI, serum, creatinine, level

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has become a routine procedure in the management of patients with coronary artery disease, it has evolved over the last 40 years since its introduction by Andreas Gruntzig in 1979.1 Technology refinement, improved stent designs, and operator experience have contributed to the current high success rates and low periprocedural complications.2 PCI outcomes are also determined by patient’s pre-procedural comorbidities. Several pre-procedural variables have been identified to predict rates of morbidity and mortality. These variables include gender, diabetes, cardiogenic shock, previous MI, serum creatinine level, left ventricular function and procedure urgency.2–6 In Saudi Arabia, the Saudi Project for Assessment of Coronary Events (SPACE) registry showed a remarkably high prevalence of diabetes mellitus among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Compared to patients from developed countries they present ten years younger.7 while post-procedural risks have been predicted by patient’s co-morbidity factors by number of studies, there are limited published studies that assessed the risks of PCI strict to the local population of Saudi Arabia. Currently, there is no published risk score model to predict mortality and morbidity following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Saudi Arabia. Thus, our objective is to develop a local clinical risk model for percutaneous coronary intervention specific to the Saudi population. We aim by conducting this research to provide insight for physicians as well as patients on the possible risks for a common procedure by providing accurate risk estimates for the Saudi population that can aid to gain better understanding of consequent risks and provide an objective base for the best treatment option.

This is a retrospective observational study of all patients above the age of 18 and under 100 years who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention at King Faisal Cardiac Center, Jeddah Saudi Arabia who met indications for revascularization and coronary stenting during the period from January 2015 till December 2017. Patients who had cardiac arrest and required intubation prior to coronary intervention as well as those who were transferred from other hospitals were excluded. All procedures for each patient were considered for analyses. Procedures were indicated according to the presence of angina, ischemia or both, and were performed either electively or urgently by experienced operators. The Decisions on the interventional techniques and devices used, and on whether to use glycoprotein. IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors and intra-aortic counter pulsation balloons were made by the attending physician. The access route of choice was the left radial artery. In all cases attempts were made to implant only second generation drug eluting stents due to lack of availability of bare metal stents in our lab. Before the intervention, all patients received aspirin (300 mg and Clopidogrel 300-600 mg orally as a single loading dose) heparin (10 000 U, except in patients receiving glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors , in which case 5000-7000 U were administered according to the weight of the patient. Baseline, procedural and hospitalization data were obtained through hospital electronic and paper file system. The main outcomes assessed in the study were in hospital mortality and major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) which included procedural death, MI, renal failure, bleeding complications, stent thrombosis, stroke, and ischemic target vessel revascularization. The study was approved by the hospital institutional review boards. Obtaining informed consent was not necessary as data collection was based on retrospective chart review.

Pre, intra- and postoperative characteristics of patients who developed MACE after PCI were compared to patients who didn't. The mean and standard deviation were used for continuous variables that had a normal distribution and were compared using the 2-sided t-test. Continuous variable that were not normally distributed were reported using the median and interquartile range and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages and were analysed by χ2 (chi square) or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. The Kruskal -Wallis test was used for ordinal variables. Univariate analysis of all variables was done. Multicollinearity was assessed using linear regression analysis. If multicollinearity existed, 1 variable was selected, based on clinical significance. Univariate logistic regression was done to assess the relationship of MACE after PCI with all potential variables with a p value=<0.1. For the multivariate analysis a step-wise logistic regression model and variables were retained if the final p value was p=<0.05. All statistical analysis and assessment of model’s performance was conducted using the R-Software, version 3.3.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing-2017).

The study included 418 patients who underwent PCI between January 2015 until December 2017. The majority of the patients were of Saudi nationality (92.4%). The mean age was 60.58 (SD±7.8). Majority were male 315 (75.36%). The most prevalent pre-procedural risk factors were hypertension in 82%, Diabetes Mellitus in 74.5%, and dyslipidaemia in 70.7% of patients. Data of four patients were missing and not included in the final analysis (Table 1). In-hospital mortality occurred in only five patients (1.2%) among the study population. All deaths occurred in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Three were complicated by refractory cardiogenic shock, one had sepsis and one due to coronary artery perforation and massive tamponade this patient had immediate cardiac surgery unfortunately he passed away. Post-procedural complications and MACE was seen in 19 patients (4.5%). Intra procedural cardiac arrest occurred in 5 patients (1.2%). Blood transfusion was required in four patients (0.96%), three of them due to post procedure access site bleeding. Other procedure related complications were, cardiac tamponade in 2 patients (0.49%) one due to oversized stent and the second due to wire perforation , non-disabling stroke in three patients (0.73%), contrast allergy (0.24%), contrast nephropathy (0.73%), new requirement for dialysis (0.49%), death in Cath lab (0.24%). The major indication for PCI was Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in 59% of the cases and STEMI in 23%. Staged and elective PCI was performed in 18 % (Table 2).

|

Characteristics (n=418) |

Values n (%) |

|

Male |

315 (75) |

|

Saudi (n=408) |

377 (92) |

|

Smoking status (n=408) |

|

|

Never |

247 (60) |

|

Former |

79 (19) |

|

Current |

82 (20) |

|

PCI Indication |

|

|

STEMI |

96 (23) |

|

NSTEMI |

240 (59) |

|

Staged |

75 (18) |

|

Median BMI (IQR) |

29.55 (25.70–33.02) |

|

Mean Age (SD) |

60.58 (±7.8) |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

310 (75) |

|

Hypertension |

342 (82) |

|

Dyslipidemia |

292 (71) |

|

Previous MI |

113 (27) |

|

Previous PCI |

155 (37) |

|

Previous CABG |

19 (5) |

|

Previous Heart Failure |

36 (9) |

|

Renal Diseases |

72 (17) |

|

Patients on Dialysis (n=224) |

19 (8) |

|

Cerebrovascular Disease |

26 (6) |

|

Peripheral Artery Disease |

8 (2) |

|

Patients on Aspirin (n=127) |

31 (24) |

|

Median Pre LVEF (IQR) |

51 (42.25–55.0) |

|

Median Pre–Trop (IQR) |

10 (1.77–666.0) |

|

Median Pre–Cr (IQR) |

80 (68.0–1122.0) |

|

Median Pre–Hb (IQR) |

13.5 (12.1–1.1) |

|

Median Pre–INR (IQR) |

1 (1.0–1.1) |

Table 1 PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; Pre LVEF, pre procedural left ventricular ejection fraction, Pre–Trop, pre procedural troponin I; Pre–Cr, pre procedural creatine; Pre–Hb, pre procedural haemoglobin; Pre–INR, pre procedural international normalized ratio

|

Variables |

Values n (%) |

|

Myocardial Infarction |

4 (0.96) |

|

Cardiogenic Shock |

4 (0.96) |

|

Heart Failure |

3 (0.73) |

|

Tamponade |

2 (0.49) |

|

Stroke |

3 (0.73) |

|

Contrast Allergy |

1 (0.24) |

|

Contrast Nephropathy |

3 (0.73) |

|

New Dialysis |

2 (0.49) |

|

Emergency CABG |

1 (0.24) |

|

Death in Cath Lab |

1 (0.24) |

|

In hospital Death |

5 (1.21) |

|

RBC/Whole Blood Transfusion |

4 (0.96) |

|

Bleeding Event within 72 Hours |

3 (0.73) |

|

Coronary Perforation |

2 (0.49) |

|

Cardiac Arrest |

5 (1.21) |

Table 2 Showing in hospital death and in hospital MACE Prevalence

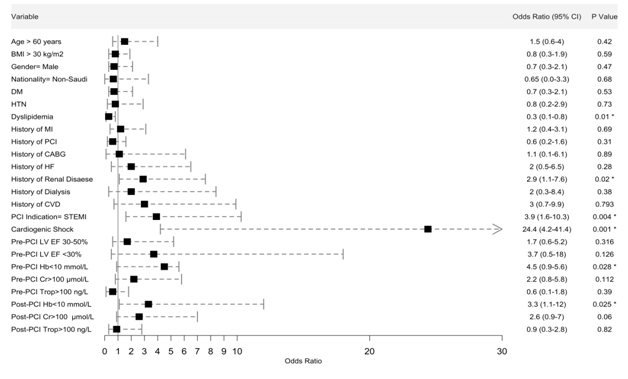

The association between certain predicators from the previous tables and the major adverse cardiac events (MACE) are illustrated in Table 3. We have identified previous renal disease, PCI indication, cardiogenic shock, pre and post procedural haemoglobin level, pre-procedural as well as post-procedural creatinine level to be associated significantly with increased in hospital MACE. It was counterintuitive to find an inverse relationship between dyslipidaemia and increased MACE. Figure 1 shows the odds ratio of these predictors and significance relationship using logistic regression testing.

|

Relationship Between MACE and Predictors |

|||

|

MACE (N=19) |

P-Value |

||

|

Yes % (N) |

No % (N) |

||

|

Age>60 years |

63.2 (12) |

53.7 (212) |

0.485 |

|

BMI >30 kg/m2 |

42.1 (8) |

48.3 (188) |

0.645 |

|

Gender=Male |

68 (13) |

75.7 (249) |

0.428 |

|

Nationality= Saudi |

5.3 (1) |

7.8 (30) |

1 |

|

Smoking |

22.2 (4) |

19.9 (77) |

0.361 |

|

DM |

68.4 (13) |

74.8 (294) |

0.592 |

|

HTN |

78.9 (15) |

82 (323) |

0.766 |

|

Dyslipidemia |

44.4 (8) |

71.6 (280) |

0.018 * |

|

Previous MI |

31.6 (6) |

27.4 (107) |

0.793 |

|

Previous PCI |

26.3 (5) |

37.9 (149) |

0.344 |

|

Previous CABG |

5.3 (1) |

4.6 (18) |

0.602 |

|

Previous HF |

15.8 (3) |

8.4 (33) |

0.227 |

|

Previous Renal disease |

36.8 (7) |

16.6 (65) |

0.032 * |

|

Previous Dialysis |

15.4 (2) |

8.2 (17) |

0.309 |

|

Previous CVD |

15.8 (3) |

5.8 (23) |

0.793 |

|

Previous Aspirin |

0 (0) |

24.2 (31) |

0.351 |

|

PCI Indication= STEMI |

52.6 (10) |

21.9 (85) |

0.004 * |

|

PCI Status= Elective |

15.8 (3) |

36.2 (141) |

0.085 |

|

Cardiogenic Shock |

15.8 (3) |

1 (3) |

0.001 * |

|

PrePCI LV EF 30-50% |

52.9 (9) |

44.5 (137) |

0.189 |

|

PrePCI LV EF<30% |

11.8 (2) |

4.5 (14) |

0.189 |

|

PrePCI Hb<10 |

16.7 (3) |

4.2 (15) |

0.049 * |

|

PrePCI Cr>100 |

38.9 (7) |

22.3 (99) |

0.147 |

|

PrePCI Trop>100 |

25 (4) |

35.5 (81) |

0.588 |

|

PostPCI Hb<10 |

25 (4) |

7.7 (24) |

0.038 * |

|

PostPCI Cr>100 |

41.2 (7) |

21.1 (70) |

0.069 * |

|

PostPCI Trop>100 |

41.7 (5) |

45 (90) |

1 |

Table 3 Showing bivariate analysis and significance relationship using anova testing. BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; HF, heart failure; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Hb, hemoglobin; Cr, creatine; Trop, troponin I. *Indicates significant res

|

Bivariate analysis of predictors for MACE POST PCI |

|||

|

Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

P-Value |

|

|

Age > 60 years |

1.5 |

0.6-4 |

0.42 |

|

BMI > 30 kg/m2 |

0.8 |

0.3-1.9 |

0.59 |

|

Gender= Male |

0.7 |

0.3-2.1 |

0.47 |

|

Nationality= Non-Saudi |

0.65 |

0.03-3.3 |

0.68 |

|

DM= Yes |

0.7 |

0.3-2.1 |

0.53 |

|

HTN= Yes |

0.8 |

0.2-2.9 |

0.73 |

|

Dyslipidemia= Yes |

0.3 |

0.1-0.8 |

0.01 * |

|

Previous MI= Yes |

1.2 |

0.4-3.1 |

0.69 |

|

Previous PCI= Yes |

0.6 |

0.2-1.6 |

0.31 |

|

Previous CABG= Yes |

1.1 |

0.1-6.1 |

0.89 |

|

Previous HF= Yes |

2 |

0.5-6.5 |

0.28 |

|

Previous Renal Disaese= Yes |

2.9 |

1.1-7.6 |

0.02 * |

|

Previous Dialysis= Yes |

2 |

0.3-8.4 |

0.38 |

|

Previous CVD= Yes |

3 |

0.7-9.9 |

0.793 |

|

PCI Indication= STEMI |

3.9 |

1.6-10.3 |

0.004 * |

|

PCI Status= Elective |

0.3 |

0.07-1.0 |

0.085 |

|

Cardiogenic Shock= Yes |

24.4 |

4.2-141.5 |

0.001 * |

|

PrePCI LV EF 30-50% |

1.7 |

0.6-5.2 |

0.316 |

|

PrePCI LV EF <30% |

43.7 |

0.5-18 |

0.126 |

|

PrePCI Hb<10 = Yes |

4.5 |

0.9-15.6 |

0.028 * |

|

PrePCI Cr>100 = Yes |

2.2 |

0.8-5.8 |

0.112 |

|

PrePCI Trop>100 = Yes |

0.6 |

0.1-1.8 |

0.39 |

|

PostPCI Hb<10 = Yes |

3.3 |

1.12-12 |

0.025 * |

|

PostPCI Cr>100 = Yes |

2.6 |

0.9-7 |

0.06 * |

|

PostPCI Trop>100 = Yes |

0.9 |

0.3-2.8 |

0.82 |

Table 4 Logestic regression analysis BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; HF, heart failure; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; STEMI, ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Hb, hemoglobin; Cr, creatine; Trop, troponin I

*Indicates significant results

Figure 1 Forest plot showing the odds ratio using Logistic regression analysis. BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; HF, heart failure; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Hb, haemoglobin; Cr, creatinine; Trop, troponin I. *Indicates significant results.

The number of percutaneous coronary intervention in Saudi Arabia is steadily rising with an expanding health care system to achieve the kingdom’s 2030 vision to improve quality of life. Many patients have now increased access to specialized cardiac facilities. Our study confirms that PCI is an effective and safe procedure at KFCC. Since 2015 the centere performs 1800 procedures annually 30 percent of those are PCI. The main purpose of this study was to identify certain clinical risk factors that can predict short term outcomes in patients undergoing PCI and use these predictors to generate a population specific risk score model; prior studies have shown poor correlation between TIMI risk score and in hospital death in local population.8 Despite the advances of PCI in the recent years early in hospital mortality and periprocedural MACE remains a concern. The in hospital mortality rate in our study was low at 1.2%. All Deaths occurred in patients presenting with STEMI which was not surprising as these patient are inherently at a higher risk of in hospital events. Shehab9 have reported an in hospital death of 5.1% among STEMI patients in the gulf region. We have previously reported an in hospital mortality of 5.2% in STEMI patient who were treated with primary PCI in Saudi Arabia.10 Our data showed high number of male patient presenting with coronary artery disease that requires PCI which was similar to what was reported by Alhabib.8 Our patients present 10 years younger than their western counterparts.7

We have also seen an alarming prevalence of risk factors like hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia and smoking this is similar to local cohort of patients reported from SPACE registry.7 Periprocedural and post-PCI complications were reported in 19 patients (4.5%).Clinically relevant complications included bleeding requiring blood transfusions, perioperative myocardial infarction, renal insufficiency, cardiac tamponade. New dialysis and non-disabling stroke. We have found a significant association between certain clinical risks and outcomes, Patients who present with STEMI, have renal disease or on dialysis, low haemoglobin before and or after the procedure and those who develop cardiogenic shock are the patients who are statistically at higher risk to develop MACE. Many of these risk predictors have been previously reported.7 Interesting finding was the inverse relationship between dyslipidaemia and out comes the reason for this is unclear as use of lipid lowering medication was not available. We did not include angiographic data describing the extent of coronary artery disease and number of coronary stents used because PCI procedures is often done in the same setting as diagnostic angiography the other reason was we were looking for Accurate assessment of periprocedural mortality before the initial angiogram at a time when the patient is not sedated and is in a better position to discuss the Risks and benefits of treatment with the physician. The aim of the study was to generate a risk score model that is specific to the local population but due to the small number of patients and low events this was not feasible. Large scale multicenter and prospective study is required. We are planning to continue to extend the study prospectively to achieve this endeavour.

Our study has many limitations, It’s a single center and a retrospective therefore has an inherent selection bias due to its observational nature, the low in hospital events and MACE though reflects safe hospital practice yet does not provide enough power to test for other unmeasured confounders, In addition the study is underpowered to generate A risk model due to extremely low events.

Percutaneous coronary intervention is a safe and effective procedure at KFCC. We have identified certain clinical predictors that are associated with increased in hospital death and MACE. Further large scale multicentre and prospective studies are required.

We would like to thank the staff of King Faisal Cardiac Center catheterization laboratory as well as the medical Students, Yousef Hussni Qari and Hani Ibrahim Barnawi for their help in data collection.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

The study was approved by King Abdullah International research centere IRB number SP17/286/J.

©2019 Bugami, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.