Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4396

Research Article Volume 14 Issue 5

1Interventional Cardiologist, Saskatchewan Health Authority: Nipawin, Canada

2Department of Cardiology, Islamic Azad University, Iran

Correspondence: Mehdi Mousavi MD, Saskatchewan Health Authority, Nipawin, Canada, Tel 15149983284

Received: July 21, 2021 | Published: September 28, 2021

Citation: Mousavi M, Akbarian M. Comparison of heart rate and symptoms in two different methods of digoxin prescription. J Cardiol Curr Res. 2021;14(5):119-124. DOI: 10.15406/jccr.2021.14.00527

Background: Medication interruption of two days a week is common in Iran to avoid the toxic effects of digoxin; however, the efficacy on symptoms and heart rate is not well studied yet.

Methods: The current clinical trial was conducted on patients receiving a digoxin regimen of 0.125mg/day or 0.25 mg/day except for Mondays and Fridays (0.25mg/day-5/7) for atrial fibrillation (AF) or heart failure (HF). After measuring digoxin level and heart rate and scoring the clinical symptoms, the enrolled patients were switched to another method of digoxin prescription. The symptoms were reevaluated after four weeks of changing the regimen of digoxin. The study was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (No. 20110512006463N2).

Results: A total of 77 patients completed the study. The mean age of the enrolled group was 65.16±11.64 years, and 44 patients (55.7%) were female. The mean digoxin level was 0.76±0.35 in the 0.125mg/day regimen, which changed to 0.94±0.56 in the 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen (P=0.034). Heart rate (HR) and daily activity scores, pain, spiritual feelings, energy, dyspnea, palpitation, nausea, blurred vision, and quality of life did not show any significant changes in the two regimens. The results of subgroup analysis in patients with AF were similar in terms of HR and symptoms, while in the subjects without AF, the scores of daily activity, dyspnea, palpitation, and quality of life significantly improved with the 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen.

Conclusions: Results of the current study showed that the HR and symptoms were not considerably different in the two regimens, whereas the digoxin level was significantly higher in the 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen. Furthermore, in the subgroup with HF but without AF, the 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen offered a better symptom control of dyspnea, palpitation, daily activity, and quality of life.

Keywords: digoxin, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, heart rate

HR, heart rate; AF, atrial fibrillation; HF, heart failure; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, LV ejection fraction

Digoxin is a well-known medication mainly prescribed to control the symptoms in advanced heart failure (HF), as well as heart rate (HR) in atrial fibrillation (AF).1-3 This medication exerts its effects by inhibiting the Na+, K+-ATPase pump in cell membranes, and cardiac myocytes.1 By increasing the rate of reaction between actin and myosin filaments, digoxin increases cardiac contractility in cardiac cell sarcomeres through increasing the concentration of intracellular calcium during systole.1,2 Another likely mechanism of digoxin action in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is sensitizing the Na+, K+-ATPase activity in vagal afferent nerves1 and ultimately increasing in the vagal tone, which is a reason for inhibiting adrenergic activity in HF.1,2 Conversely, the higher doses of digoxin may show sympathomimetic effects.1,2 This increased sympathetic tone and increased calcium load lead to an increased rate of spontaneous (phase 4) diastolic depolarization, which is a potential cause for arrhythmias.1

When digoxin is prescribed for patients with HFrEF, end-systolic and diastolic volume and end-systolic pressure of left ventricle (LV) decreases and consequently, there might be an improvement in cardiac output and LV ejection fraction (LVEF).2 There is some evidence that 1 to 3-month treatment with digoxin can improve symptoms, quality of life, and exercise tolerance regardless of underlying rhythm (AF or sinus rhythm).4 Furthermore, adding digoxin to the standard regimen of symptomatic patients with HFrEF decreases the hospitalization and admission time, and withdrawal of digoxin from the therapeutic regimen may aggravate the symptoms.1,5,6 However, recent concerns about the possibility of an increased risk of mortality in HFrEF patients7-9 have been influential in restricting its prescription in these patients by current guidelines.10 In fact, with the availability of newer medications and treatment options, nowadays, digoxin is a second line medication in the management of HFrEF in the absence of response to other medications including diuretics. Nevertheless, in patients with HFrEF, adding digoxin to a beta-blocker has the advantage of better control of HR at rest.1,11 Hence, digoxin is still an appropriate choice in heart rate and symptom control of the patients with HFrEF and atrial fibrillation.

Digoxin also shows electrical effects on sinoatrial (SA) and atrioventricular (AV) nodes by decreasing the rate of impulse production in SA nodes and lowering conduction speed, and extending the refractory period in AV nodes.1,2 Furthermore, digoxin decreases the HR in AF by increasing vagal tone;1 therefore, it is used to control heart rate in AF1-3 and is definitely superior to placebo, but inferior to beta blockers.12 However, digoxin might not provide enough HR control during exercise and usually, beta-blockers are preferred over digoxin for this purpose in AF.1-3 Therefore, digoxin is almost an obsolete drug for the treatment of atrial fibrillation or supraventricular tachycardia alone.

Digoxin is well absorbed when administered orally (65%-80%), but it is also available intravenously. The drug effects are observed 5-30 minutes after injection and 2-5hours after oral intake.2 The medication is mainly metabolized by renal root;1,2 about 20%-25% of it is bound to proteins, and it has a half-life of about 36-40hours.2 Digoxin, primarily used by plants to kill mammals in nature, is highly toxic and has a low therapeutic index; this is why digoxin serum blood levels should be carefully monitored.1 Cardiac arrhythmias, heart block, neurologic complaints such as visual disturbances, disorientation, and confusion, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, as well as increased mortality are some adverse effects of digoxin overdose.1 Adverse effects are also reported in patients with acute myocardial infarction.13

Digoxin is commonly used with an interruption of two days a week.14-17 Since the only available oral form of the medication in our country is 0.25mg tablets, many physicians prefer to prescribe 0.25mg/day, except one or two days per week (0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen) to avoid inadvertent toxic effects.14-17 The off days are usually Mondays and Fridays and rarely two consecutive days are suggested for a drug holiday.

According to digoxin (DIG) trial, the optimal digoxin serum level to exert positive inotropic effects and favorable neurohormonal inhibition is 0.5 to 1.0ng/Ml.1,4,9 Higher concentrations might be associated with increased mortality.1,5,9 The oral maintenance dose of digoxin is 0.0625 to 0.25mg/day, depending on renal function, body size, and the presence or absence of co-administered medications. For a great majority of patients, the usual preferred dose is 0.125mg daily.1 A daily dosage of 0.125mg provides 0.875 mg/week of medication in comparison with 1.25mg/week in 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen. On the other hand, symptoms may aggravate after the day medication is not taken. Therefore, the current study mainly aimed at comparing the HR and some symptoms, including palpitation and dyspnea in two different regimens of digoxin prescription (0.125mg/day versus 0.25mg/day except Mondays and Fridays).

The current clinical trial study was conducted on patients who needed treatment with digoxin for symptom control of HF or heart rate control of permanent persistent AF. Patients under treatment with digoxin from private and hospital clinics (Imam Hussein Hospital, or Khatam-Al-Anbia Hospital) of a single town (Shahroud, Iran) consciously were included if the patients consented to participate in the study.

The included patients were patients with heart failure who received the treatment with digoxin in addition to other standard medications. The patients required to be on a fixed regimen for at least one month prior to the trial and there was no need for any changes in medications for any reason such as dyspnea, hypertension control, heart rate control, or increasing the dosage of the drug to reach the recommended target dose. Furthermore, the patients were instructed to take their digoxin in the evening.

The patients were excluded if,

Include patients who initially took 0.125mg/day digoxin regimen (54 patients) were switched to 0.25mg daily, except Mondays and Fridays (0.25mg/day-5/7). Conversely, those who initially took 0.25mg/day-5/7 (26 patients) were switched to 0.125mg/day method.

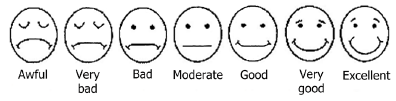

The patients were visited on Saturdays to evaluate the symptoms (one day after the drug holiday in 0.25mg/day-5/7 digoxin regimen), and heart rates were obtained using ECG. A visual function questionnaire (Figure 1) was given to the patients to record their clinical symptoms, including daily activity, pain, spiritual feelings, energy, dyspnea, palpitation, nausea, blurred vision, and quality of life. The patient independently provided a score of 1 to 7 for each symptom (describing the symptom as excellent, very good, good, moderate, bad, very bad, and awful). Digoxin serum levels were obtained 6-8 hours following the last digoxin dose.1

Figure 1 Visual score questionnaire used in the study to score clinical symptoms including exercise tolerance, palpitation, dyspnea, chest pain, nausea from 1.

Then, after the treatment was switched, heart rate measurement, scoring, and digoxin level measurements were repeated. The investigator who assessed heart rate or digoxin level was blinded about the mood of drug intake, but the patient was not blinded.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated based on a pilot study and assuming a change in the mean HR of 7 beats/minute after changing the regimen.

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The normal distribution of continuous variables was assessed by the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (for >50 subjects) or the Shapiro-Wilk test (for <50 subjects), as well as histograms. Numerical variables were presented as means ± SDs if they showed a normal distribution or as median, interquartile range if they did not follow a normal distribution. Paired samples t-tests were used to compare data before and after the changing digoxin regimen in each patient if it had a normal distribution. If this did not show normal distribution, non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The local Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University approved the study protocol. Written consent was obtained from all patients after they were informed about all possible consequences and side effects. The study was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) website (No. IRCT20110512006463N2).

Totally, 84 patients were evaluated to enter the study, but four were excluded (one due to increased creatinine, one due to hospitalization, and two due to nausea, vomiting). Among the 80 included patients, 58 (72.5%) had AF, and 22 (27.5%) received digoxin only for HF. The mean age of the enrolled subjects was 65.16±11.64 years, of which 44 (55.7%) were female. Three patients did not complete the follow-up, and thus, 77 patients with completed follow-ups were analyzed for symptoms.

Table 1 provides the basal characteristics, as well as digoxin levels and HR of the patients. A comparison of these parameters in two subgroups of patients with AF and HF patients without AF are also given in Table 1.

|

Variable |

Total (n=77) |

Patients with AF (n= 56) |

HF Patients without AF (n=21) |

|

Age (years) |

64±11.25 |

66.5±13.66 |

63.00±10.37 |

|

Sex (female) |

44 (57.1%) |

38 (66.7%) |

6 (30.0%) |

|

Height (m) |

1.6 [1.5, 1.7] |

1.5 [1.4, 1.7] |

1.66 [1.6, 1.7] |

|

Weight (kg) |

71.49±13.99 |

72.68±14.43 |

68.10±12.37 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

29.21±6.20 |

30.62±6.12 |

25.19±4.50 |

|

Patients taking 0.125 mg/d digoxin in first visit |

55 (71.4%) |

20 (100%) |

35 (61.4%) |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) in first visit |

0.9 [0.8, 1.1] |

0.8 [0.8, 1.109] |

1 [0.9, 1.2] |

|

Digoxin level (ng/ml) at 0.125mg/day |

0.76±0.35 |

0.62±0.28 |

0.82± 0.37 |

|

Digoxin level (ng/ml) at 0. 25mg, 5/7days |

0.94±0.56 |

0.74±0.40 |

1.02±0.61 |

|

Heart rate (beat/min) at 0.125mg/day |

70 [65, 83] 77.62±18.94 |

74 [65, 95] 80.63±20.11 |

67 [60.75, 77] 69.05 ±11.81 |

|

Heart rate (beat/min) at 0.25mg/day, 5/7 |

72 [64. 5, 80] 75.85±16.01 |

75 [67.5, 80] 78.23±17.18 |

67 [61.25, 73.88] 69.08±9.51 |

Table 1 A comparison of basic characteristics, digoxin levels and heart rates of patients with and without atrial fibrillation

AF, Atrial fibrillation; BMI, Body mass index; HF, Heart failure

Table 2 compares the HR, digoxin level, and the scores given to different symptoms (from 1 to 7) in two different methods of digoxin prescription (0.125mg/day versus 0.25mg/day-5/7) and the two subgroups of patients with or without AF. The mean digoxin level was 0.76±0.35 in 0.125mg/day regimen, which changed to 0.94±0.56 in 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen (P=0.034, Table 2). Meanwhile, the HR did not show any significant changes in the two regimens (P=0.615, Table 2); indeed, 42 patients (54.5%) had lower HRs when switched to 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen, while 35 (45.5%) showed higher HRs after switching. Scores of daily activity, pain, spiritual feelings, energy, dyspnea, palpitation, nausea, blurred vision, and quality of life did not show significant differences in the two methods of digoxin prescription (Table 2).

|

Variable |

Digoxin 0.125mg/day |

Digoxin 0.25mg/day-5/7 |

P value |

|

Digoxin level (ng/ml) |

0.76±0.35 |

0.94±0.56 |

0.034* |

|

Patients with AF |

0.62±0.28 |

0.74±0.40 |

0.294* |

|

HF patients without AF |

0.82±0.37 |

1.017±0.61 |

0.069* |

|

Heart rate (beat/min) |

70 [65, 83] |

72 [64.5, 80] |

0.615** |

|

Patients with AF |

74 [65, 95] |

75 [67.5, 80] |

0.682** |

|

HF patients without AF |

67 [60.75, 77] |

67 [61.25,73.88] |

0.837** |

|

Daily activity score |

5 [3, 5] |

5 [3, 6] |

0.549** |

|

Patients with AF |

3[3, 5] |

3 [2, 5] |

0.925** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [5, 6]5 |

6 [5, 6] |

0.025** |

|

Pain score |

4 [3, 5] |

4 [3, 5] |

0.191** |

|

Patients with AF |

4 [3, 5] |

4 [3, 5] |

0.275** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [4, 5] |

5 [4, 5] |

0.480** |

|

Spiritual feeling score |

4 [ 3, 5] |

4 [3, 5] |

0.498** |

|

Patients with AF |

4 [3, 5] |

4 [3, 5] |

0.686** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [5, 5] |

5 [5, 5.75] |

0.498** |

|

Energy score |

4 [4, 5] |

4 [4, 5] |

0.763** |

|

Patients with AF |

4 [4, 4] |

4 [4, 4] |

0.257** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [4, 5] |

5 [4.25, 5] |

0.275** |

|

Dyspnea score |

5 [4, 5] |

5 [3, 5] |

0.659** |

|

Patients with AF |

4 [3.5, 5] |

5 [3, 5] |

0.813** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [4, 5] |

5 [4.25, 6] |

0.021** |

|

Palpitation score |

5 [3.5, 5] |

5 [3, 5] |

0.330** |

|

Patients with AF |

4 [3, 5] |

5 [3, 5] |

0.527** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [5, 5] |

5 [5, 5.75] |

0.046** |

|

Nausea score |

5 [5, 5] |

5 [5, 5] |

0.330** |

|

Patients with AF |

5 [5, 5] |

5 [5, 5] |

>0.999** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [5, 5] |

5 [5, 5.75] |

0.317** |

|

Blurred vision score |

5 [4, 5] |

5 [5, 5] |

0.851** |

|

Patients with AF |

5 [4, 5] |

5 [ 4, 5] |

0.851** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [5, 5] |

5 [5, 5] |

P>0.99** |

|

Quality of life score |

4 [4, 5] |

4 [4, 4.5] |

0.052** |

|

Patients with AF |

4 [4, 4] |

4 [4, 4] |

0.564** |

|

HF patients without AF |

5 [4.25, 5] |

5 [4.25, 6] |

0.011** |

Table 2 A comparison of digoxin level, heart rate, and scores given to different symptoms in two different methods of digoxin prescription (0.125mg/day versus 0.25mg/day-5/7) and the subgroup analysis in patients with AF or heart failure patients without AF

AF, atrial fibrillation; HF, Heart failure

* Pair T-test, ** Wilcoxon signed-rank test

The subgroup analysis in patients without AF (n=21, Table 2) showed that in this subgroup, scores of daily activity, dyspnea, palpitation, and quality of life significantly improved when the medication was prescribed with a 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen.

The current study was conducted to compare the HR, digoxin level, and subjective symptoms of patients receiving two regimens of digoxin treatment (0.125mg/day versus 0.25mg/day-5/7). It was observed that the HR and scores of daily activity, pain, spiritual feeling, energy, dyspnea, palpitation, nausea, and blurred vision were not significantly different in the two regimens. In contrast, the digoxin level was significantly higher (0.94 ± 0.56 versus 0.76 ± 0.35 ng/mL, P=0.034, Table 2) and the scores of quality of life tended to be higher (P=0.052, Table 2) in the 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen.

Most previous studies compared 0.25mg/day dosage with 0.25mg/day-5/7 and showed that digoxin levels were significantly higher when it was taken every day, leading to the recommendation that 0.25 mg/day of medication might provide a better treatment.14-16 Nevertheless, it should be considered that at the time of these studies, the therapeutic range of digoxin was defined as 0.8-2.0ng/mL. In contrast, currently, according to digoxin trials, a digoxin level of 0.5 to 1ng/mL is preferred to avoid increased mortality.1,5 Therefore, the current study compared the lower recommended dosage of 0.125mg/day with 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimens.

The subgroup analysis showed that in patients with AF, the digoxin level, HR, and all of the scores did not have significant differences in the two regimens (Table 2). However, among patients without AF receiving digoxin only for the symptoms of HF, scores of daily activity, dyspnea, palpitation, and quality of life significantly improved, and digoxin level tended to be higher (0.82±0.37 versus 1.017±0.61, P= 0.069) when digoxin switched to 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen (Table 2). A higher level of digoxin could explain this improvement in symptoms.

According to the DIG trial, mortality might be directly related to the digoxin serum levels of more than 1.12ng/mL,1 and low serum digoxin concentrations might even reduce mortality and hospitalization.18 These observations led to the suggestion that the levels of digitalis should be kept between 0.5 and 0.9ng/mL.4 In the current study, digoxin levels were in the suggested therapeutic range in both 0.125mg/day and 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimens; therefore, both regimens could be used safely in the patients with normal creatinine levels similar to the current study group.

In both 0.125mg/day and 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimens of digoxin, the HR was significantly higher in patients with AF compared with the ones without AF (P <0.05, Table 1). On the other hand, the HR did not show any significant change when the patients switched from 0.125mg/day to 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen totally and in any of the subgroups separately (Tables 2). Some other trials on patients with AF showed that when digoxin is prescribed 0.25mg/day compared with an interrupted regimen of 0.25mg/day-5/7 the mean HR of patients was significantly lower and digoxin levels were higher.14,15 Based on the results of the current study, changing the regimen from 0.125mg/day to 0.25mg/day-5/7 could not be helpful in terms of HR control. A regimen of 0.25mg/day may offer better control of HR compared with the 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen.9 However, according to the results of RACE II study, this further HR control might be of no benefit in terms of clinical outcomes19 and there is a concern about increasing the digoxin level in the higher dose of the medication. Therefore, we recommend either a 0.125mg/day or 0.25mg/day-5/7 for HR control of patients with HFrEF and AF.

Since digoxin is mainly removed by kidneys, in the current study, the patients with a serum creatinine level of >1.6mg/dL or the ones with an increase of more than 1mg/dL during the trial were excluded. Hence, the results of the current study could be used in patients with relatively good renal function. The current study finding in patients without AF needs to be confirmed with higher power studies.

Our included patients were dependent on treatment with digoxin for heart rate control of AF or symptom control of HF, and deprivation from medication or prescription of placebo was not possible. Instead, every patient in our study served as its control to compare the effect of two methods of digoxin prescription. Moreover, due to the nature of our study, which was mainly designed to compare two methods of digoxin consumption, we were not able to make the patients blinded to the treatment regimen, which may have some effect on their assessments.

The current study results showed that both 0.125mg/day regimen and 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen with Mondays and Fridays holidays were almost equal in the HR and symptom control in a group of patients with creatinine levels <1.6 mg/dL. However, the digoxin level was significantly higher in 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen and in subgroup patients without AF (who indeed had HF with normal sinus rhythm), the 0.25mg/day-5/7 regimen offered a better symptom control in terms of dyspnea, palpitation, daily activity, and quality of life.

The current research was performed as a thesis for Medical Doctor Degree by Dr. Mahsa Akbarian according to the rules of Islamic Azad University. The authors wish to thank Dr. Jafar Tahmasbi for his great help in data collection and Dr. Niloofar Barzegar and Dr. Saman Afrasiabi for providing some articles and helping to improve the manuscript.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interest towards this manuscript.

None.

©2021 Mousavi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.