Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4396

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) represents an abnormal communication between the pulmonary arteries and veins. Symptoms occur slowly with the increasing size of PAVM and they are represented by dyspnea, epistaxis and hemoptysis, which, sometimes, can be severe leading to the death of the patient. On the other hand, atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and oral anticoagulants (OAC) represent an efficient treatment in stroke prevention. In this paper we discuss a case of PAVM clinically manifested with massive hemoptysis, and which associated atrial fibrillation that needed oral anticoagulation.

Keywords: Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation; Atrial fibrillation; Oral anticoagulants

Described for the first time in 1897 during an autopsy, pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) represents an abnormal communication between the pulmonary arteries and veins, usually being congenital [1]. About 80%of the patients with PAVM have hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT or Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) [2], but PAVM can also appear after a trauma, thoracic surgical intervention, neoplasms or other diseases such as mitral stenosis, amyloidosis and others [3]. Symptoms occur slowly with the increasing size of PAVM and they are represented by dyspnea, epistaxis and hemoptysis, which, sometimes, can be severe leading to the death of the patient [3]. So, it is a condition with a high risk of bleeding.

On the other hand, atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, in 2010, worldwide were estimated 20.9 millions of people suffering from atrial fibrillation, and in 2030, only in the European Union, it is estimated a number of 14 to 17 millions of patients with atrial fibrillation, since each year about 120000-215000 patients are being diagnosed with this disease [4]. Patients suffering from atrial fibrillation have a risk of cerebral embolic stroke of 20-30%, and oral anticoagulants (OAC) represent an efficient treatment in stroke prevention [4]. In patients who have a high risk of bleeding from the PAVM and who, also, associate atrial fibrillation, the treatment with OAC is difficult to administrate [5]. In this paper we discuss a case of PAVM clinically manifested with massive hemoptysis, and which associated atrial fibrillation that needed oral anticoagulation.

A 57-year-old man who was admitted in January 2016 to the emergency room of the Emergency County Hospital of Craiova for cough and massive hemoptysis (about 800 ml of blood). About 10 years ago, the patient presented repeated hemoptysis (4-5 episodes of 100 ml of blood each); after investigations such as computed tomography and bronchoscopy the suspicion of a vascular cause of these hemoptysis was taken into account. An arteriography of the bronchial arteries was performed and it revealed a small hipervascularized area in the left superior bronchial artery, which did not need interventional embolization at that time. Medical treatment including antitussives, seven days of antibiotics, vitamins and flebotonics and also periodic cardiological and pneumological reevaluation were recommended. Now he is at the second episode of hemoptysis.

The patient was never a smoker, he has no history of any allergy, he has never used illicit drugs and he did not take any medication at home. He had the following vital signs: temperature of 36.7 °C, irregular heart rhythm, about 142 beats per minutes, blood pressure 165/95 mmHg, respiratory rate about 26/min, oxygen saturation while breathing in ambient air 94%. In what physical examination is concerned the patient was awake, orientated, with equally round and reactive to light and accomodation pupils, normocephalic, atraumatic, mucous membranes moist, normal oculomotricity, anicteric sclera and intact tympanic membrane; neck with no jugular veins distension, with no lymphadenopathy. He had irregular heart rhythm (about 142 beats per minutes), and no murmurs, normally complied thorax, vesicular murmur bilaterally present, no rales, no rhonchi or wheezes, no egophony, no alteration in tactile fremitus and normal percution. His abdomen had no pathological elements, liver, spleen in normal limits. He had no peripheral edema and extremities without cyanosis, his teguments were intact, with a normal color and temperature. The neurological and psychiatric examinations were normal. At the laboratory examination he had the following constants: at complete blood count a hemoglobin of 10.6 g/dl, a hematocrit of 30%, 12300/mm3 leukocytes, 210000/mm3 platelets; normal renal (creatinine of 0.86mg/dl) and hepatic (GOT, GPT, γ-GT, ALP, total, direct and indirect bilirubin) functions, inflammatory markers represented by fibrinogen (468 mg/dl), normal values of the electrolytes (Na+, K+, Ca++, MG ++, Cl-). The values obtained at the arterial gasometers revealed a pH of 7.4, pCO2 of 33 mmHg and a PaO2 of 63 mmHg. The INR was 0.9, the APTT was 18,2 seconds and Quick Time 125%.

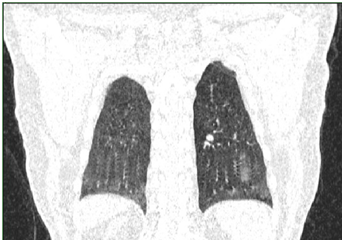

Routine 12-lead ECG at rest showed atrial fibrillation with a heart rate of 142 beats per minute, with no diffuse or nonspecific alterations of the repolarization phase; QRS axis was at +20 degrees. Computed tomography revealed air-trapping phenomena associated with lesions of subpleural fibrosis and bronchiectasis in the superior ventral and left apical segments, without tumor or condensation processes. In the apical territory of the left inferior and dorsal-ventral lobe, dilated, permeable vascular structures sized to 2.7 cm were identified, having an aspect of PAVM and which represent the cause of the hemoptysis (Figures 1-4); without pleural and pericardial effusion, without lymphadenopaties.

The patient was hospitalized in the Intensive Care Clinic where he received treatment with hemostatic, antibiotics, antitussives and antihypertensive (Candesartan 8 mg). For atrial fibrillation Amiodarone was administrated slowly intravenous with a rhythm of 5 mg/kg in an hour, achieving the conversion of the atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. During hospitalization the patient repeated the hemoptysis in moderate quantity (100-300 ml), and that is the reason he is guided to the interventional radiology service from the Ares Hospital in Bucharest. Here, the selective catheterization of all the arterial branches of the descending aorta’s thoracic segment was performed. A right bronchial artery and two left bronchial arteries having an increased size and a tortuous path were identified. Left bronchial arteries were supraselectively catheterized by using a 2.4F microcatheter and they were embolized with glubran and lipiodol. Right bronchial artery was embolized with gelaspon fragments. The statis of the contrast was obtained in all these vessels.

Subsequent, the patient returns in the Cardiology Clinic of the Emergency County Hospital of Craiova because he suffers again from atrial fibrillation. After new intravenous administration of Amiodarone conversion to sinus rhythm was achieved. That is why, besides the treatment with Candesartan of 8 mg, the decisions of administrating three times a day 150 mg of Propafenone and also of initiating the treatment with 5 mg twice a day with Apixaban were taken; after the supraselectiv embolization of the bronchial arteries, which participated to the PAVM, the bleeding risk was removed. HAS-BLED score before the supraselectiv embolization of the bronchial arteries was 2 and after the embolization was 1, while CHA2DS2-VASc Score was 1. The patient was released with an indication of a reevaluation after four weeks in order to reevaluate the long term anticoagulant indication of therapy.

PAVM is rare in general population, an incidence of 2-3 per 100000 people [3]. More than 80% of the PAVM appear in patients with HHT, which have four diagnostic criteria: epistaxis, telangiectasia, visceral lesions and an appropriate family history [2,6]. In the case we presented the patient has no familiar antecedents of HHT, no muco-cutaneous lesions of HHT and he never had recurrent epistaxis, but due to his clinical features he was included in the high risk bleeding by PAVM category. The embolization is the first line treatment, and its criteria include symptomatic PAVM and also asymptomatic lesions that have vessels with a diameter higher than 3 mm [3]. This new way of treatment has a smaller morbidity than the traditional surgical method, and so it can be performed whenever needed [3].

Atrial fibrillation is a major risk factor for the stroke and thromboembolic history. It is a real therapeutic problem when both the bleeding risk and the risk of stroke are high. In what the management of the patients with atrial fibrillation is concerned the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines sustains that the treatment with oral anticoagulants must be taken into account when speaking of men having a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 and of women having a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 [4]. In our case, as an oral anticoagulant treatment we chose a non-vitamin K oral antagonist anticoagulant, Apixaban, which is a direct inhibitor of Xa factor [7].

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.