Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 5

1Community medicine and Public health Department, Faculty of medicine, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

2Anesthesia Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt

3Radiology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt

Correspondence: Khaled Kasim, Community medicine and Public health Department, Faculty of medicine, Al-Azhar University, Egypt, Tel 201064964291

Received: October 31, 2016 | Published: December 30, 2016

Citation: Kasim K, Barakat AM, Abdelhamid T (2016) Ultrasound-Guided Interscalene Nerve Block: An Alternative Technique to Anatomical Landmark-Guided Approaches. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access 6(5): 00243. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2016.06.00243

Background: The use of ultrasonography in interscalene brachial plexus block (ISBPB) has rapidly evolved over the past few years. It has been speculated that ultrasound guidance might increase success rates and reduce complications.

Objective: The aim of our study is to compare the success rate and safety of ISBPB performed either with ultrasound visualization or with anatomical landmark to guide needle placement.

Methods: A total of 44 patients scheduled for shoulder and upper arm surgeries in Zagazig University hospital, Zagazig, Egypt, were included in this prospective study and randomized into two equal groups according to the guidance method for ISBPB. In the ultrasound group (group A), the brachial plexus was visualized with a linear 38-mm, high frequency 7 MHz probe and the spread of the local anesthetic was assessed. In anatomical landmark group (group B), the roots of the brachial plexus were located by eliciting parasthesias when the target nerves were touched by the needle.

Results: Surgical anesthesia was achieved in 91% of patients in group A vs. 73 % of patients in group B (p= 0.01). The dose of anesthesia was significantly lower in group A compared to group B. Also, duration of anesthesia was increased and the need for analgesia was reduced in group A. The incidence of complications was significantly higher in group B (45%) than in group A (18%) (p= 0.01).

Conclusion: The use of ultrasonography helps to improve the efficacy and to reduce the complications associated with ISBPB.

Keywords: brachial plexus, nerve block, regional anesthesia, ultrasonography

Interscalene brachial plexus block (ISBPB) is a common nerve block given to patients who are undergoing shoulder and upper arm surgery. The block involves injection of local anesthetic in the interscalene groove between the anterior and middle scalene muscles to block the brachial plexus.1 In the past landmarks were used for finding the location of the interscalene groove and needle placement there was expected to elicit parasthesias when the target nerves were touched by the needle. If the correct parasthesias were produced, the needle was assumed to be in the right place and local anesthetic was injected slowly with intermittent aspirations to assure that the local was not being injected into the intravascular space or intrathecally.1,2 Later in the history of the procedure, nerve stimulators replaced needle-induced parasthesias relieving the clinician of the need “touch” the nerves.3,4 The nerve stimulator results, however, are still not a reliable indicator of proximity to nerves in many cases. Neuropathies from diabetes or peripheral vascular disease can render the nerve stimulators useless for even finding the nerves let alone indicating the needle proximity to them.5

All things being equal, the block would then either work or not and would be accompanied by several dangers owing to the proximity of the target nerves and to other important structures such as the vertebral artery, the dome of the pleura, the cervical spinal cord, the carotid artery and internal jugular vein. Injection in any of these structures could lead to very unpleasant complications and even death.3 The recent use of ultrasound-guided techniques to facilitate the placement of regional anesthesia blocks is the result of a search for more consistent and safer methods of nerve localization. Ultrasound guidance has been found to be helpful during the performance of brachial plexus anesthesia, particularly since advanced equipment with compound imaging and high-resolution probes have become available.5 Since, in most cases, the nerve trunks can be easily identified, placement of the needle to an optimum position next to the nerve trunks can be accomplished in a single needle pass and that help to decrease the suspected complications during injection.6,7 Although the above mentioned advantages of the ultrasound-guided ISBPB over the anatomical landmark procedure, there is still debate about the efficacy and usefullnes of the use of such a procedure and further researches are needed to ascertain the impact of ultrasound guidance on block success rates and safety.8 The present study aimed to compare the efficacy; in terms of success, dose and duration of anathesia as well as the need of analgesia and the safety of ultrasound versus anatomical landmark guided ISBPB. The success was defined as excellent muscle relaxation during surgery

A prospective randomized, single-blind study was conducted in Zagazig University hospitals, Zagazig, Egypt to compare the efficacy and safety of the ultrsound-guided ISBPB versus anatomical landamrk ISBPB. In this study, 44 patients scheduled for upper extremity surgeries were randomized, by simple randomization, into two equal groups, and receive either an ultrasound-guided (group A) or anatomical lanmark guided (group B) interscalene brachial plexus block, during the defined six months period of the study. Exclusion criteria included age <18 years or >75 years, ASA > III, pregnancy, neuropathy, neurologic disease, pre-existing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), unstable asthma, renal or hepatic impairment. All patients were informed about the procedures and its complications and a written consent was obtained.

ISBPB technique

Anatomical landmark guided ISBPB: The roots of the brachial plexus are found in the interscalene groove between the anterior and middle scalene muscles at the level of the cricoid cartilage (C6) in the neck. The interscalene groove is located lateral to the anterior scalene muscle and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The surface anatomy is made before block. Then, the needle is introduced slowly slightly dorsal, slightly cauded, and in medial direction in order to minimize risk of entering the cord. After an appropriate parasthesia is elicited local anaethetic is injected incremently with frequent negative aspiration.

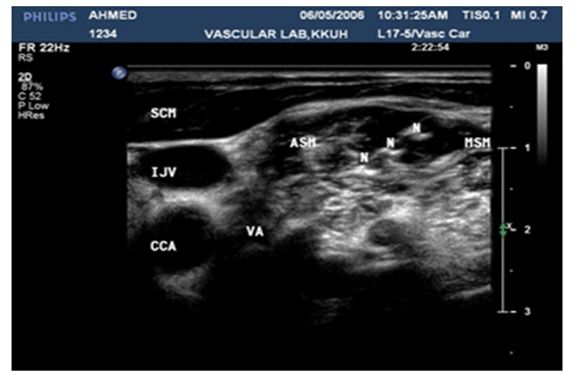

Ultrasound guided ISBPB: After application of standard monitors, patients were lightly sedated and verbal responsiveness was maintained throughout the block. The nerves in the interscalene space were identified by U-S (Titan®, SonoSite Inc., Bothell, WA), at approximately the level of the cricoid cartilage in the transverse or short-axis view. The footprint of the linear, 7 MHz transducer was then outlined by a marking pen, the skin was prepped and draped in a sterile fashion, and the transducer was enclosed in a sterile sleeve. After skin anesthesia, a 50-mm, 22-guage insulated needle (Stim-A2250, B. Braun Medical, Inc., Bethlehem, PA) was advanced under U-S guidance until the tip of the needle was between the two most lateral nerves in the interscalene space. These nerve structures are most likely the C5 and C6 roots, or the upper trunk and the C7 root/middle trunk.9 The block needle was advanced in the long axis of the transducer (in plane), so that the shaft and tip of the needle were always in view. Once the tip of the needle was positioned, and after negative aspiration, a local anesthetic was injected incrementally over 2–3 min with intermittent negative aspiration. Local anesthetic is seen as a hypoechoic fluid collection between the two scalene muscles (Figure 1). All the studied patients were injected by local anesthetic (we use 12 to 25 mL of bupivicaine, 0.5%, with epinephrine, 1:400,000).

Figure 1 SCM: Sterno Cleidomastoid Muscle; ASM: Anterior Scalene; MSM: Middle Scalene Muscle; IJV: Internal Jugular Vein; CCA: Common Carotid Artery; VA: Vertebral Artery

Age, sex, associated medical diseases, other than those excluded, ASA class, local anesthetic dose, the need for analgesia and sedation, efficacy and duration of the block, and any complications were recorded for both groups. The collected data were managed and analyzed confidentially and anonymously by using statistical analysis system (SAS) program, version 9.0. Differences between the two groups were evaluated using independent samples t-test for continuous data and x2 test for difference in categorical data. All relevant comparisons were two sided and the significant level was accepted at p value ≤ 0.05.

The patients in this study were comparable and no differences were noted in both group characteristics. Table 1 presents the charcteristics of the studied patients in both group. The mean age of the patients as well as the distribution of ASA class and associated medical diseases were nearly the same both groups. However, more males were included in the ultrasound-guided ISBPB group (group A) compared with anatomical landmark ISBPB group (group B), but with no statistically significant difference. Table 2 shows the outcome of ISBPB by the used procedure. The success rate was significantly higher group A than in group B. The success rate was 91.0% and 73.0% in both groups respectively (p= 0.01).

Characteristics* |

Ultrasound guided Group A |

Anantomical landmark-guided Group B |

P value |

Age |

42.8 ± 20.1 |

42.9 ± 18.7 |

0.99 |

(18,71) |

(18,75) |

||

Sex |

|||

Male |

17 (77.0) |

15 (68.0) |

0.5 |

Female |

5 (23.0) |

7 (32.0) |

|

ASA class |

|||

Class I |

15 (68.0) |

15 (68.0) |

0.81 |

Class II |

5 (23.0) |

6 (27.0) |

|

Class III |

2 (9.0) |

1 (5.0) |

|

Associated diseases |

|||

Free |

15 (68.0) |

15 (68.0) |

1 |

Hypertension |

3 (14.0) |

2 (9.0) |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

2 (9.0) |

2 (9.0) |

|

Ischemic heart diseases |

2 (9.0) |

3 (14.0) |

|

Table 1 Comparison of patients’ characteristics in both groups (ultrasound and anatomical landmark guided ISBPB)

*Data are presented by mean ± SD and (range) or by n (%).

ISBPB success* |

Ultrasound-guided Group A |

Anantomical landmark-guided Group B |

P value |

Success |

20 (91.0) |

16 (73.0) |

0.01** |

Failure |

2 (9.0) |

6 (27.0) |

|

Table 2 Outocome of ISBPB in both groups (ultrasound and anatomical landmark guided ISBPB)

*Data are presented n (%).

**Significant

Table 3 presents the mean dose of the used anaesthetic, onset and duration of action as well as the need of post operative analgesia in both studied groups. There has been a highly statistically significant differences (p= 0.001) between the two groups with regard to the dose of the used anasthetic with the lower mean dose was observed in group A. On the other hand, however, no statistically sigificant differences were observed between the two groups with regard to the onset of action and duration of anaethesia, although the mean onset tended to be lower and the mean duration tended to be higher in group A. In that group, the need of analgesia is found to be less than that observed in group B, but with no statistically significant difference. Table 4 presents the complication associted with the procedure in both groups. The incidence of overall complications was significantly lower in group A (18%) compared with that in the in anatomical landmark guided group (45%). Phrenic nerve palsy, horsness of voice and horner’s syndrome were lower group A than in group B with statistically significant difference (p= 0.01).

*Anaesthesia related Factors |

Ultrasound guided Group A |

Anantomical landmark guided Group B |

P value |

Dose of anesthesia (ml) |

28 ± 5.1 |

35.0 ± 5.2 |

0.0001** |

(20,40) |

(25,45) |

||

Onset of action (minutes) |

8.9 ± 4.6 |

9.8 ± 3.9 |

0.51 |

(3,20) |

(3,20) |

||

Duration of action (minutes) |

74.0 ± 12.5 |

70.0 ± 15.9 |

0.41 |

(55,95) |

(50,90) |

||

The need for analgesia |

0.22 |

||

No |

18 (82.0) |

16 (73.0) |

|

Yes |

4 (18.0) |

6 (27.0) |

Table 3 Dose, onset and duration of duration of anaethesia in both studied groups (ultrasound and anatomical landmark guided ISBPB)

*Data are presented by mean ± SD and (range) or by n (%).

**Significant

Complication* |

Ultrasound guided Group A |

Anantomical landmark-Guided Group B |

P value |

No complication |

18 (82.0) |

12 (55.0) |

0.01** |

Phrenic nerve palsy |

1 (4.5) |

3 (13.5) |

|

Horsness of voice |

2 (9.0) |

4 (18.0) |

|

Horner’s syndrome |

1 (4.5) |

3 (13.5) |

|

Table 4 Associated complication in both groups (ultrasound and anatomical landmark guided ISBPB

*Data are presented by by n (%).

**Significant

The ultrasound guided interscalene nerve block resulted in more successful brachial plexus block than did the surface landmark guided procedure. In most of similar studies, the success rate of U/S guided ISBPB was better and exceeding 90%, even in children,10 than that of surface landmark ISBPB approach.11,12 Although the onset of complete block was not significantly different between the two groups, there was a slight delay in onset of complete block, particularly, in patients with surface landmark approach. This finding may have been because of the nonhomogenous distribution of motor, sensory, and connective tissue in nerve roots,13,14 such that a needle may have been proximate to one fiber type whereas at some distance from another type.15

Compared with surface landmark approach group, the dose of anesthesia was reduced and the duration of nerve block was extended in the U/S guided group. In a practice setting where patients receive nerve block for shoulder surgery, the most important end point was considered to be the adequacy and duration of upper trunk block, because this may be all that is necessary for post operative shoulder analgesia.16 In this study, 18% of patients in U/S group needed post operative analgesia compared to 27% of patients in the other group.

A higher percentage (45%) of patients in group B, where surface landmark approach was used, had complications compared to only 18% in group A, where U/S approach was used. The use of U/S in ISBPB provides good and clear visualization of all anatomical structures, and may reveal anatomical variations. In most cases, the nerve trunks can be easily identified, placement of the needle to an optimum position next to the nerve trunks can be accomplished in a single needle pass and that help to decrease the suspected complications during injection.6,7

A shortcoming of the study design is that the hospital nurses recorded outcome data, and they were not blinded to the current determined during block performance. They were not, however, aware of the predetermined study objectives and the randomized group division, which should reduce the potential for bias. Furthermore, comparing the ultrasound-guided ISBPB to the anatomical landmark guided ISBPB technique may be considered a limitation in this study as the anatomical landmark guided ISBPB is not the usual standard technique. However, as the use of electrical stimulation was not available at the studied hospitals, we were compelled to use this unusual standard technique. This point will be taken into consideration in our future researches.

The results of this study added to the literature that recommends the use of ultrasound for guidance of brachial plexus blocks. However, large scaled multicentric studies are needed to confirm this recommendation.

We would like to thank all participated patients for their cooperation. We also thank the operating theatre nurses in Zagazig university for their helping and recording the data.

There is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2016 Kasim, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.