Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Case Report Volume 1 Issue 5

Department of Surgery, Nagasaki Prefecture Shimabara Hospital, Japan

Correspondence: Yuichi Sanada, Department of Surgery, Nagasaki Prefecture Shimabara Hospital, 7895 Shimokawajiri, Shimabara, Nagasaki 855-0861, Japan, Tel 81957631145

Received: October 22, 2014 | Published: October 31, 2014

Citation: Sanada Y, Mishima T, Azuma T, Matsuo S (2014) The Role of Nutritional Management in the Clinical Course of Severe Complications Associated with the Pancreas after Abdominal Surgery: Presentation of Four Cases. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access 1(5): 00026. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2014.01.00026

Background: All surgeons should note that complications associated with the pancreas after abdominal surgery can be severe and can induce life-threatening problems such as sepsis, abdominal abscess, and intra-abdominal hemorrhage. In such situations, nutritional management is a key element of therapy to achieve a favorable clinical course.

Methods: We reviewed the clinical course of four patients with complications associated with the pancreas after abdominal surgery from January 2012 to March 2013, focusing on nutritional management.

Results: Two patients developed postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) induced by failure of pancreatoenteric anastomosis after pancreatoduodenectomy. Because we had placed a feeding jejunostomy tube intraoperatively in each of these patients, enteral feeding through these tubes was increased to attenuate catabolic stress in parallel with locoregional therapy, which led to early improvement of the general condition and closure of the fistula in these patients. One of the other two patients developed acute pancreatitis induced by anastomotic stenosis of the duodenojejunostomy after segmental duodenectomy, and the other developed pancreatic fistula after resection of the left kidney and urinary tract with excision of the retroperitoneal soft tissues. These patients had no route for enteral feeding. Prolonged total parental nutrition affected their longer time to recovery.

Conclusion: Placement of a feeding jejunostomy tube at the initial operation may play a crucial role not in the prevention but in the management of complications associated with the pancreas.

Keywords: Enteral nutrition, Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Complication

POPF, Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula; EN, Enteral Nutrition; RCT, Randomized Clinical Trial; POD, Post-operative Day; DGE, Delayed Gastric Emptying

Complications associated with the pancreas after abdominal surgery, such as pancreatic fistula and pancreatitis, are potentially life-threatening conditions that can lead to bleeding, intra-abdominal abscess, and septic shock.1 When surgeons encounter these complications, not only locoregional intervention, re-operation or drainage, but also the general management of the patient, including nutritional therapy, are important to achieve a favorable clinical course. Of these complications, pancreatic fistula induced by failure of the anastomosis after pancreatoduodenectomy is relatively common. The International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery established the definition of and grading systems for postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) after pancreatoduodenectomy to gain insight into international consensus.2 In addition, recent randomized clinical trials (RCTs) based on this consensus have revealed that enteral nutrition (EN) is associated with significantly higher closure rates and shorter time to postoperative closure of the pancreatic fistula.3 Therefore, it is natural that EN plays important roles in the treatment of pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy.

However, the risk of complications associated with the pancreas is not limited to cases of pancreatic resection. In abdominal surgery, several manipulations around the pancreas are performed to create a good operative field. For example, the caudal edge of the pancreas should be transected to mobilize the left mesocolon, and the retropancreatic fascia is dissected to expose the anterior space of the left adrenal gland. Therefore, when abdominal operations include such manipulations, surgeons should pay close attention to injury of the pancreas that could lead to associated complications. We report four consecutive cases of severe postoperative complications associated with the pancreas, including two cases not involving pancreatic resection, focusing on the nutritional support provided during postoperative treatment.

The clinical features of the four cases are summarized in Table 1 and 2.

Case |

Age/Sex |

Underling Disease |

Disease for Surgery |

Surgical Procedure |

Complication Associated with the Pancreas |

Case 1 |

76/M |

Hypertension Renal dysfunction |

Malignant lymphoma of retroperitoneal space |

Left nephrectomy with adrenal resection |

Pancreatic fistula Retroperitoneal abscess |

Case 2 |

64/M |

(-) |

Intramural haemotoma of the duodenum |

Segmental duodenectomy |

Obstructive pancreatitis |

Case 3 |

75/M |

Renal dysfunction |

Bile duct carcinoma |

Pancreato duodenectomy |

Pancreatic fistule Abdominal abscess(Leakage of the pancrea to jejunostomy) |

Case 4 |

60/M |

(-) |

Duodenal carcinoma |

Pancreato duodenectomy |

Pancreatic fistule Abdominal abscess(Leakage of the pancrea to gastrostomy and hepatico-jejunostomy) |

Table 1 Clinical features of the four cases 1

M, Male

Case |

Onset of the Complication Associated with the Pancreas |

Sepsis |

Severe DGE |

Therapy for Complication |

Placement of Feeding Jejunostomy |

Period of Therapy for Complication |

Case 1 |

POD 8 |

(+) |

(+) |

Drainage |

POD 28 |

49days |

Case 2 |

POD 8 |

(+) |

(+) |

Re-operation |

POD 29 |

45days |

Case 3 |

POD 9 |

(+) |

(+) |

Drainage |

POD 0(intra operative placement) |

20days |

Case 4 |

POD 8 |

(-) |

(+) |

Drainage |

POD 0(Intraoperative placement) |

40days |

Table 2 Clinical features of the four cases 2

POD, Post-operative Day; M, Male

Case 1

A 76-year-old man underwent surgery for a giant malignant lymphoma localized in the left retroperitoneal space. The primary tumor showed extensive growth replacing the left kidney and urinary tract, with infiltration to the retroperitoneal fascia and soft tissues around the dorsal space of the pancreas. The left kidney and urinary tract were excised with the tumor, circumventing the extensive adhesion between the pancreas and the anterior aspect of the tumor. A closed drain was placed at the left retroperitoneal cavity. The drainage tube had yielded amylase-rich fluid from postoperative day (POD) 3. On POD 7, the patient developed hyperpyrexia with marked backache and reflexive vomiting.

Purulent fluids showing high amylase values were obtained from the drainage tube. Fistulography revealed an extensive abscess occupying the left retroperitoneal space. Based on these findings, a pyogenic abscess in the retroperitoneum induced by postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) was diagnosed (Figure 1). Despite continuous lavage by saline and intermittent vacuum through the drainage tube, severe renal dysfunction progressed through general consumption by septic condition (Figure 2). In addition, the patient’s reflexive vomiting and severe delayed gastric emptying (DGE) made it difficult to insert a nasojejunal tube as a feeding route. On POD 28, a 10 Fr nasojejunal tube was inserted beyond the ligament of Treitz under gastrography, and EN was then combined with parental nutrition. The patient’s general condition including renal function improved in parallel with the volume expansion resulting from the calorie intake through the nasojejunal tube. The abscess gradually reduced in size, and on POD 50, the drainage tube was removed after disappearance of the abscess cavity was confirmed. The patient was discharged on POD 60 in good condition. The patient has shown no signs of recurrence for 2 years after surgery.

Case 2

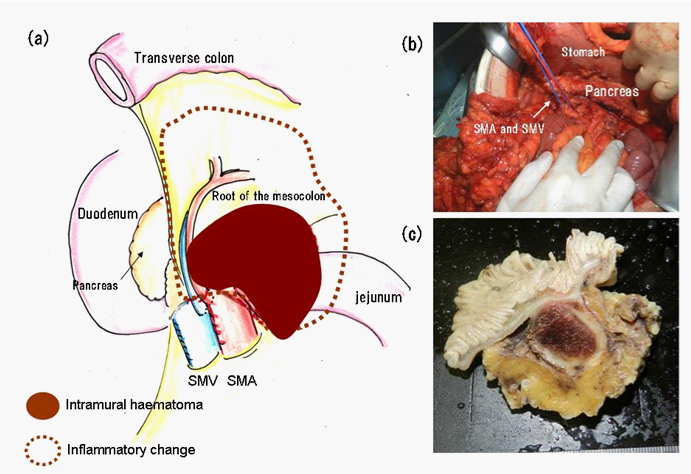

A 61-year-old man underwent surgery for intramural hematoma located in the 3rd portion of the duodenum. The lesion was palpable as a firm mass, infiltrating to the root of the mesocolon and pancreatic tissues in the head of the pancreas. The infiltrative tissues around the mass were carefully dissected with the LigaSure system (Manufacturer’s name, Location). The 2nd and 3rd portions of the duodenum including the mass were resected, and an end-to-end anastomosis was constructed. The anastomotic site was located distal to the ampulla of Vater (Figure 3). On POD 3, following copious bile-stained vomiting, the patient became febrile. Decompression by nasogastric tube slightly relieved his suffering. From POD 10, the patient had begun to complain of a sense of epigastric heaviness (Figure 4). A computed tomography scan showed dilation of the duodenum proximal to the anastomotic site and enlargement of the pancreas with inflammatory change of the peripancreatic soft tissues. Gastroduodenography using Urografin revealed narrowing of the 2nd portion of the duodenum. From these findings, we inferred that stricture of the anastomotic site had induced accumulation of pancreatic juice and bile, leading to pancreatitis (Figure 5).

Figure 3 Images and schematic presentations of operative findings and resected specimen in case 2. (a) The intramural haemetoma is localized in the root of the mesentery adjacent to the superior mesenteric vessels with consolidation induced by marked inflammation. (b) An image after segmental duodenectomy. The caudal edge of the pancreas is excised. (c) Cur surface of the resected specimen shows intramural haemetoma localized in the subserosal layer.

Because conservative treatment did not restore his condition, we performed re-laparotomy on POD 28. Abdominal exploration revealed marked consolidation of the peripancreatic fatty tissues, including that of the transverse mesocolon and greater omentum, forming a giant mass 10 cm in diameter. The duodenum including the anastomotic site and transverse colon penetrating the mass was accompanied by marked dilation of the proximal lumen. To improve the luminal obstruction of the duodenum and transverse colon and to reduce pancreatic inflammation, a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy and side-to-side ileosigmoidostomy were performed. In addition, a feeding jejunostomy tube was placed intraoperatively in the upper jejunum (Figure 6). On the third day after the second surgery (new POD 3), EN was initiated through the feeding jejunostomy combined with parental nutrition. Although severe DGE persisted for 3 weeks, it gradually disappeared in parallel with improvement of the pancreatitis (Figure 7). Oral intake began from new POD 20. Gastrography revealed good passage of contrast through the gastrojejunostomy. The patient was discharged in good condition on new POD 35.

Case 3

A 74-year-old man underwent pancreatoduodenectomy for inferior bile duct adenocarcinoma. An end-to-side pancreatojejunostomy was performed incorporating the pancreatic duct and the full thickness of the jejunum using interrupted 4-0 synthetic absorbable sutures with an external stent. The outer layer consisted of interrupted 4-0 Maxon sutures placed through the seromuscular layer of the jejunum and through the capsule of the pancreas into the cut edge. An end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy was also fashioned with interrupted 4-0 Maxon sutures. A gastrojejunostomy was performed with an antecolic jejunal loop, and a feeding jejunostomy tube was placed in the upper jejunum distal to the Braun anastomosis. A drainage catheter was placed at the anterior aspect of the pancreatojejunostomy. EN was started on POD 2. The patient pursued a good clinical course during the acute stage after surgery. Oral intake started on POD 7.

However, on POD 9, the patient developed bouts of fever followed by pronounced vomiting and back pain. The drainage catheter yielded frank pus including necrotic tissues. On the evening of POD 9, he became septic. After sufficient fluid resuscitation, fistulography was performed through the drainage catheter, which revealed intra-abdominal fluid collection and a communication between the fluid collection and the jejunal loop, suggesting anastomotic failure of the pancreatojejunostomy (Figure 8). Continuous lavage using saline through the drainage catheter was begun on POD 10. Intake of calories through the feeding jejunostomy was gradually increased up to 2000 kcal/day, including 1.5 g amino acids/kg per day (Figure 9). In parallel with the improvement of inflammation associated with the POPF, both his malnutrition and severe renal dysfunction were gradually relieved. Oral intake began on POD 37. The drainage tube was removed on POD 44 after confirmation of the disappearance of the abscess cavity.

Figure 8 A schematic presentation of postoperative pancreatic fistula induced by anastomotic failure of pancreatojejunostomy in case 3.

Case 4

A 60-year-old man underwent pancreatoduodenectomy for duodenal carcinoma. A pancreatogastrostomy, hepaticojejunostomy, and gastrojejunostomy were performed by one surgeon. Because the wall of the common hepatic duct was thin and vulnerable, an external biliary drainage tube was placed through the jejunal loop beyond the hepaticojejunostomy. A percutaneous transperitoneal jejunal feeding tube was placed and passed into the efferent jejunal loop. Occlusive drainage catheters were positioned behind the cranial and caudal edges of the pancreatogastrostomy. Enteral feeding was started 24 hours postoperatively at 20 ml/h. The administration rate was increased daily until the full nutritional goal of 1200 kcal/day was reached on POD 3. On the evening of POD 3, the patient experienced sudden, intense epigastric pain spreading rapidly throughout the right upper quadrant.

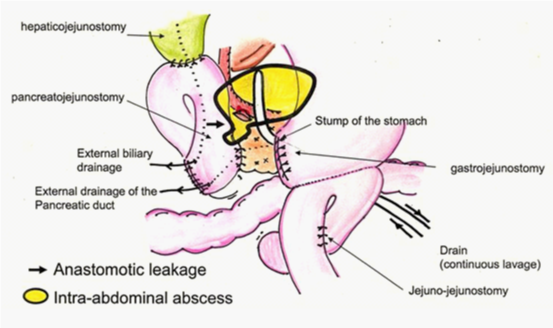

Laboratory tests showed elevation of his serum direct bilirubin level. Cholangiography using Urografin revealed anastomotic leakage of the hepaticojejunostomy. Fluid collection was observed around the dorsal space of the hepaticojejunostomy. Because the external drainage tube was placed at the common hepatic duct near the anastomotic site, administration of antibiotics promptly improved the symptoms associated with the anastomotic leakage of the hepaticojejunostomy. Oral intake was started on POD 7. On POD 8, the patient developed a high fever. Tan suppurative fluids were obtained from the intraperitoneal drainage tubes. Fistulography through the drainage tubes revealed intraabdominal fluid collection around the anastomotic site of the pancreatogastrostomy, communicating to the remnant stomach.

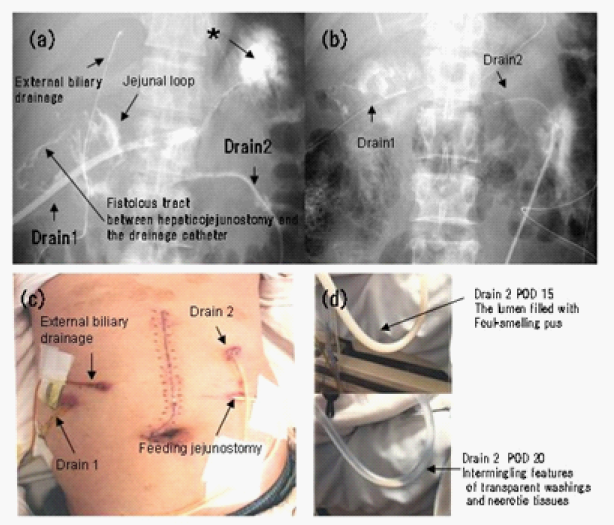

We concluded that anastomotic leakage at the two anastomotic sites (hepaticojejunostomy and pancreatogastrostomy) had occurred (Figure 10). Continuous lavage by saline and intermittent vacuum through the bilateral drainage tubes were started on POD 10. To attenuate the patient’s marked catabolic stress, enteral feeding containing 110 g protein was increased daily to a maximum of 3000 kcal/day on POD 16 (Figure 11). Enteral feeding was safely and well tolerated without negative effects except for mild abdominal distension. In parallel with the improvement of the inflammation associated with the anastomotic leakages, the patient’s general condition also improved remarkably (Figure 12). The left drainage tube was removed on POD 50 after healing of the POPF. Oral intake was begun on POD 51.

Figure 10 Images and a schema of postoperative pancreatic fistula induced by the anastomotic failure of pancreatogastrostomy accompanied by anastomotic failure of hepaticojejunostomy in case 4.

Figure 12 Postoperative drainage in case 4. (a) A fistolography on POD 21. Communication with the stomach and the tip of the drainage catheter 2 is visualized (*). (b) A Fistolography on POD 48. Closure of the fistula is confirmed. (c) Image of the abdomen during drainage and enteral feeding. (d) The attribution of fluids obtained by drainage catheter 2 shows gradual alleviation of pancreatic fistula.

We presented four consecutive cases of postoperative severe complications associated with the pancreas. Of these, two cases (cases 3 and 4) were of severe POPF induced by failure of the pancreatoenteric anastomosis. In our department, a percutaneous feeding jejunostomy feeding tube is routinely placed at the upper jejunum beyond all anastomoses during surgery in the case of oesophagectomy and major pancreatic resection, because of the long period of convalescence required following surgery and the need to restrict oral intake until the anastomosis has sufficiently healed.

Although it has been generally accepted that postoperative EN is useful in the management of major abdominal surgery,4 few studies have shown that postoperative EN is superior to total parental nutrition for patients who have undergone pancreatoduodenectomy.5‒8 In fact, most clinical studies have not been able to demonstrate the effectiveness of EN in the clinical course of these patients.9‒15 Shen et al. reported that EN appeared safe and tolerable for patients after pancreatoduodenectomy, but they did not show advantages in terms of infectious complications and postoperative hospital stay by accumulation of data from recent RCTs.16 In addition, the guidelines for preoperative care for pancreatoduodenectomy established by the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery society indicate that patients should be allowed a normal diet after pancreatoduodenectomy and that enteral tube feeding should not be placed routinely.17 Based on these descriptions, postoperative EN after pancreatoduodenectomy does not appear to contribute to the general postoperative course.

However, the effectiveness of EN after pancreatoduodenectomy has been discussed only with respect to the reduction of postoperative complications, such as DGE, POPF, and other infectious complications, and to length of hospital stay. Once patients develop severe complications including POPF after pancreatoduodenectomy, they can easily develop life-threatening conditions, such as abdominal abscess, sepsis, and intraabdominal hemorrhage. In addition, severe POPF impairs intestinal function, as represented by DGE and paralysis of the upper intestinal tract around the anastomotic sites, leading to longitudinal fasting.18

Given that the catabolic state induced by POPF requires sufficient caloric intake, the presence of a feeding jejunostomy tube beyond all of the anastomoses allows safe enteral feeding, a key element of conservative therapy, leading to the attenuation of catabolic stress and improvement of intestinal function. 19pointed out that a jejunostomy allows enteral therapy for longer periods, especially in patients with complications. In our cases 3 and 4, progressive increase of caloric intake could be smoothly performed through the feeding jejunostomy tube from the day after onset of anastomotic failure. Although the patient in case 3 had severe renal dysfunction exacerbated by his complications, we could attain the full nutritional goal, including 1.5 g/kg protein, in parallel with the locoregional intervention. Gradual improvement of renal function has been observed during enteral therapy. 20 reported that EN is more effective at ameliorating liver and kidney function after pancreatoduodenectomy.

We speculate that enteral feeding during the management of complications after pancreatoduodenectomy serves not only as a key element for improvement of malnutrition but also as maintenance of organic function. In case 4, leakage occurred at two anastomotic sites, the pancreatogastrostomy and hepaticojejunostomy. To achieve early closure of intractable fistulas and attenuate the severe infectious condition, caloric intake of twice the basal energy expenditure, including 120 g protein/body, was administered through the jejunostomy tube. In 2011,3 reported that enteral feeding is associated with significantly higher closure rates and shorter time to closure of the postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. This RCT is unique in that they localized the clinical significance of enteral feeding after pancreatoduodenectomy not to the prevention of postoperative complications but to the management of postoperative complications.

On the basis of these descriptions, we believe that the intraoperative placement of a feeding jejunostomy tube in cases 3 and 4 played a crucial role in the treatment of the postoperative complications. A prominent feature in the present case series is that postoperative complications associated with the pancreas occurred in two patients (cases 1 and 2) who underwent abdominal operation without pancreatic resection. Surgeons need to recognize the possibility that complications associated with the pancreas, such as pancreatic fistula, can be induced by intraoperative manipulations performed around the pancreas. In case 1, the primary tumor aggressively infiltrated into the retro-pancreatic soft tissues, requiring careful dissection of the tumor from the pancreas, which, unfortunately, led to slight injury of the pancreas. Because we did not place a feeding jejunostomy tube intraoperatively, we could not perform EN after the onset of pancreatic fistula. We attempted to place a nasojejunal tube several times but failed due to reflexive vomiting induced by the patient’s severe DGE. On POD 28, we could finally place a nasojejunal tube beyond the ligament of Treitz under gastrography. After enteral therapy was started through the nasojejunal tube, the abscess gradually reduced in parallel with the improvement of renal function and attenuation of the patient’s catabolic stress.

The pathogenesis of the postoperative complication in case 2 was acute pancreatitis induced by stenosis of the duodenojejunostomy and intraoperative injury of pancreatic tissues. The patient had also undergone total parental nutrition until POD 28, when a feeding jejunostomy tube was placed during re-laparotomy. In addition, the patient had been managed under peripheral parental nutrition from POD 21 to POD 28 because of removal of the central venous catheter due to catheter-associated infection. Pancreatitis and severe DGE were aggravated only under parental nutrition that provided insufficient caloric intake. Many RCTs and guidelines have recommended that the initiation of early jejunal feeding is associated with reduced mortality in patients with severe acute pancreatitis.21,22

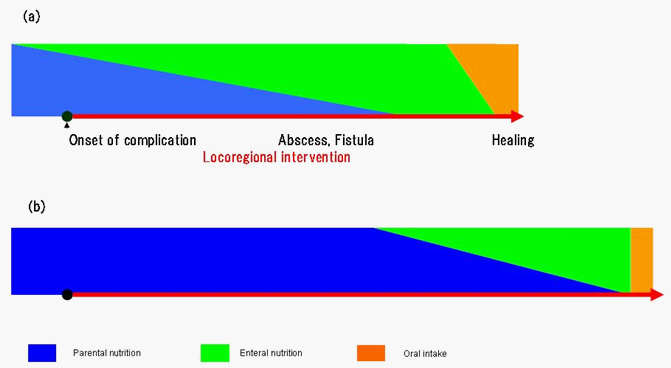

We speculate that placement of a feeding jejunostomy tube at the initial operation in patients predisposed to the onset of this severe complication might avoid deterioration of the pancreatitis. The clinical courses of case 1 and 2 share common features in the following three aspects. First, lack of the route for enteral feeding adversely affected the management of complications associated with the pancreas, leading to the prolonged periods (more than 40 days) for treatment of the complications. Second, severe DGE induced by the complications made it difficult to place the jejunostomy tubes. Third, initiation of the delayed enteral feeding yielded clinically apparent improvement in several aspects: closure of the fistula, attenuation of the infection and catabolic stress, and maintenance of organ function. It should be noted that feeding jejunostomy plays a crucial role not in the prevention but in the management of complications associated with the pancreas, even in operations without pancreatectomy (Figure 13).

Figure 13 Hypothetical models of postoperative course in cases of complications associated with the pancreas. (a) Earlier initiation of enteral feeding through feeding jejunostomy tube placed intraoperatively is needed to optimize clinical conditions after complications. (b) Delayed initiation of enteral yields prolonged periods of therapy for complications.

Although the clinical courses in this case series support the role of jejunal feeding in resolving the complications associated with the pancreas, the underlying mechanisms are unclear. The mechanisms by which jejunal feeding improve complications associated with the pancreas may be explained from the following two viewpoints, reduction of pancreatic secretion and motility of the stomach. First, pancreatic secretions may be reduced under enteral feeding. In contrast with parental nutrition, enteral feeding through the jejunostomy generally not only avoids pancreatic stimulation but also can stimulate the release of specific gut peptides forming a negative feedback control system, thus inhibiting pancreatic secretion. Second, enteral feeding through the jejunostomy may offer a mechanical effect that stimulates the motility of the stomach and jejunum, improving DGE.3 Further studies are needed to ascertain the role of feeding jejunostomy in the management of complications associated with the pancreas.

None.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest.

©2014 Sanada, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.