Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Mini Review Volume 5 Issue 2

Consultant Intensive Care Medicine at Private practice clinic, Iraq

Correspondence: Fadhil Zwer, Consultant Intensive Care Medicine at Private practice clinic, Iraq

Received: June 15, 2016 | Published: July 7, 2016

Citation: Zwer-Aliqa FK (2016) Sivelestat and Thrombomodulin Treatment for ALI/ARDS. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access 5(2): 00180. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2016.05.00180

BPM, beats per minute; POD, postoperative days; CVP, central venous pressure; MOD, multiple organ dysfunction; MBP, mean blood pressure

Sivelestat (trade name: Elaspol) (Figure 1) is a selective neutrophil elastase inhibitor, was found to be effective for reducing the length of ICU stay and the ventilator-assisted period for patients with ALI/ARDS in a multicenter clinical study conducted in Japan, but surprisingly, similar efficacy has not been found in other countries. This may in part be because ALI/ARDS is associated with a wide variety of underlying diseases, and the patient characteristics may be too heterogeneous for determination of therapeutic efficacy. Therefore, the therapeutic effect of sivelestat on ALI/ARDS requires evaluation in a population with more homogeneous etiology of the underlying disease.

Sepsis is a major cause of extrapulmonary ALI/ARDS and is associated with high mortality. In patients with sepsis, marked accumulation of in the lungs is found in the early stages. ALI/ARDS arising from abdominal sepsis is associated with lung tissue damage caused by neutrophil elastase released from activated neutrophils, active oxygen, or other factors. Because sivelestat selectively inhibits neutrophil elastase without having effects on other proteases, this drug may be effective in ALI/ARDS associated with abdominal sepsis.

Sivelestat contributed to early improvement in PaO2/Fi2O, improvement in MOD score, and shorter periods of ventilator assistance and ICU stay for patients with ALI/ARDS following surgery for abdominal sepsis (Table 1). Generally, selective neutrophil elastase inhibitors reduce pulmonary inflammation and improve pulmonary function.1 In multicenter clinical studies, sivelestat contributed to early weaning from a ventilator in ALI/ARDS patients, resulting in early transfer to a general ward. However, in STRIVE (Sivelestat Trial in ALI Patients Requiring Mechanical Ventilation), no efficacy of sivelestat was found in patients with ALI/ARDS, even in the ventilator-assisted period, and there was no effect on mortality. It was found that in an early ALI/ARDS is thought to be a condition for which sivelestat is likely to demonstrate efficacy.2 Significant reductions in the ventilator-assisted period and length of ICU stay in the sivelestat group of patients may have occurred because the therapeutic intervention was performed in the early stage of lung injury, and was supported by real-time observation.

|

Parameter |

Group |

ICU admission |

POD 1 |

POD 2 |

|

pH |

Sivelestat |

7.35±0.10 |

7.42±0.06 |

7.44±0.06 |

|

Non-sivelestat |

7.36±0.07 |

7.41±0.07 |

7.41±0.05 |

|

|

PaO2/FiO2 (mmHg) |

Sivelestat |

171±62 |

288±89 |

294±79 |

|

Non-sivelestat |

182±65 |

228±70 |

246±61 |

|

|

PaCO2 (mmHg) |

Sivelestat |

42±11 |

37±6 |

37±6 |

|

Non-sivelestat |

37±7 |

37±9 |

38±5 |

|

|

Heart rate (bpm) |

Sivelestat |

119±18 |

95±18 |

85±16 |

|

Non-sivelestat |

119±12 |

111±9 |

101±11 |

|

|

MBP (mmHg) |

Sivelestat |

68±23 |

86±12 |

88±13 |

|

Non-sivelestat |

81±16 |

84±15 |

85±13 |

|

|

CVP (mmHg) |

Sivelestat |

11.8±3.3 |

11.3±3.1 |

9.0±3.4 |

|

Non-sivelestat |

12.1±5.4 |

11.6±3.4 |

10.1±3.5 |

|

|

Platelet (104/µl) |

Sivelestat |

13.4±7.7 |

12.4±6.8 |

13.4±7.4 |

|

Non-sivelestat |

14.7±9.8 |

11.5±8.4 |

9.1±8.3 |

|

|

MOD score |

Sivelestat |

7.9±3.3 |

4.8±3.0 |

4.5±3.3 |

|

|

Non-sivelestat |

7.3±3.0 |

7.1±2.9 |

6.5±3.4 |

Table 1 Changes in blood gas values; hemodynamics, platelet and MOD score.4

The highly heterogeneous causes of ALI/ARDS provide a further difficulty in studying the efficacy of sivelestat. ALI/ARDS develops several hours after the onset of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome associated with sepsis. One of the primary target organs for neutrophil sequestration is the lung; thus, neutrophils are largely involved in the onset of ALI/ARDS associated with sepsis. All patients who had ALI/ARDS associated with abdominal sepsis, and thus neutrophil elastase inhibitors may have limited the progression of ALI/ARDS. The early improvement in MOD score in patients treated with sivelestat might be explained by improvement in PaO2/FiO2 and maintenance of the platelet count. Neutrophil elastase promotes platelet aggregation, and thus sivelestat has anti-platelet activity and maintains the platelet count. The postoperative platelet count was maintained in the sivelestat group of patients and was significantly higher than that in the non-sivelestat group of patients. Furthermore, a decrease in platelet count after surgical invasion contributes to activation of neutrophils and endothelial cells. Therefore, the most results were suggesting that sivelestat inhibits activation of these cells by maintaining the platelet count, and thereby indirectly prevents onset and progression of ALI/ARDS.

The ventilation period and length of ICU stay decreased significantly in the sivelestat group of patients. This result is consistent with the improvements seen in lung injury and MOD score. Because sivelestat is a neutrophil elastase inhibitor, its use in the early stages of ALI/ARDS is likely to be effective. In patients with ALI/ARDS associated with abdominal sepsis onset of ALI/ARDS due to infection can be predicted during surgery, which makes it feasible to initiate sivelestat in the early stage after onset. This contributes to inhibition of excessive secretion of neutrophil elastase and neutrophil accumulation, thereby inhibiting further inflammation, ameliorating SIRS, and improving pulmonary function. In addition, platelet function is maintained and activation of neutrophils and endothelial cells is inhibited, thereby allowing direct and indirect prevention of lung injury.

Control of excessive production of inflammatory cytokines may reduce surgical mortality. It has been shown that perioperative use of a neutrophil elastase inhibitor is beneficial for reducing the stress caused by invasive surgical procedures. Perioperative administration of sivelestat may reduce surgical stress by decreasing cytokine release and preserving anti-tumor immunity. Such modulation of excessive inflammatory cytokine production may improve surgical morbidity. Preoperative administration of a neutrophil elastase inhibitor has also been found to suppress increases in interleukin-6 and to be useful for reducing surgical stress.3

Thrombomodulin (TM) is a transmembrane protein ex-pressed on the endothelial cell surface that plays an important role in the regulation of intravascular coagulation.4 The biological agent recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin (RHTM) was approved and is being used clinically for the treatment of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC). The effects of rhTM on DIC were previously examined in a multicenter randomized clinical and the resolution of DIC was significantly better in the patients treated with rhTM than in the patients treated with unfractionated heparin. The rhTM binds to thrombin to inactivate coagulation and the thrombin-rhTM complex activates protein C to produce activated protein C (APC), which, in the presence of protein S, inactivates factors VIIIa and Va, thereby inhibiting the further thrombin formation. Acute respiratory distress syndrome is also characterized by excessive intra -alveolar fibrin deposition, driven at least partly by inflammation. The imbalance between the activation of coagulation and inhibition of fibrinolysis in patients with ARDS appears to occur both systemically in the lungs and the alveoli. The activation of Tissue Factor (TF) is a critical event that results in thrombin formation. Thrombin is a key inter-mediate molecule with several biological functions, including the augmentation of vascular permeability and enhancement of inflammation. Thrombin generation leads to fibrin polymerization and deposition, with the resultant formation of hyaline membranes and a pathological hallmark of ARDS. The modulation of coagulation and fibrinolysis has a complex effect on both haemostatic and inflammatory pathways. Therefore, anticoagulation therapy is beginning to be recognized as a potential new strategy for the treatment of ARDS patients.

It was suggested that activated intravascular coagulation disturbances occurred in ARDS patients be-cause of elevated levels of plasma Fibrinogen Degradation Products (FDP) (normal range is ˂5µg/ml) and Thrombin-Antithrombin complex (TAT) (normal range is ˂4ng/ml). The modulation of the coagulation disturbance by conventional therapy with rhTM administration may be related to the mortality of ARDS patients, because the serial changes in the fibrinogen and plasma TAT, and the SpO2/FIO2 level showing the respiratory conditions significantly increased in ARDS patients. It was found that additional rhTM administration appeared to be safe, without any major adverse effects.

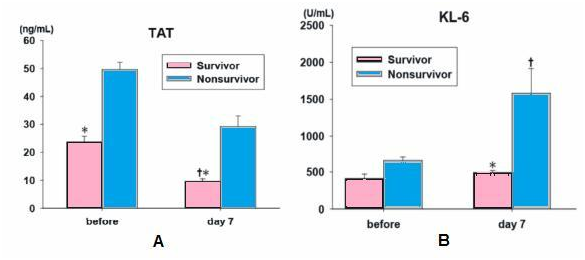

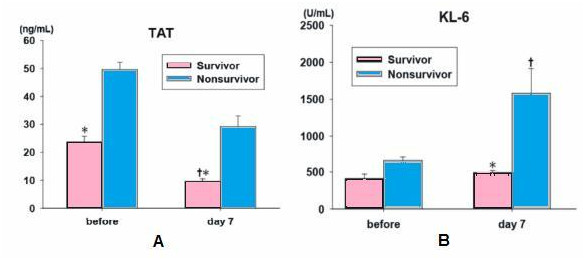

Tissue factor expression, a key mediator of the activation of coagulation in the lungs and fibrin deposition were detected by the presence of specific antibodies in the alveolar space and the pathogenesis of the early phase of ARDS. The imbalance between the activation of coagulation and inhibition of fibrinolysis in patients with ARDS appears to occur both systemically and in the alveolar space. Therefore, rhTM, which can modulate the coagulation pathway, such as the protein C pathway and the antithrombin pathway, may be useful for the treatment of ARDS (Figure 2a).

Figure 2a The plasma TAT showed significantly lower levels in survivors before the ad-ministration of rhTM. On day 7, the plasma TAT level in survivors was significantly lower that the initial level and the level of nonsurvivors *P<0.05 compared to the nonsurvivors, †P<0.05 compared to before treatment. FDP, fibrinogen degradation products; TAT, thrombin-antithrombin complex.

Figure 2b On day 7, serum KL-6 levels in survivor showed significant lower compared to that of nonsurvivors and serum KL-6 levels in nonsurvivors showed significant higher compared to before the administration of rhTM. *P<0.05 compared to the nonsurvivors, †P<0.05 compared to before treatment. IL-6, interleukin-6; HMG-1, high-mobility group-1 protein; KL-6, Krebs von den Lungen-6.5

On day 7, the plasma TAT level in survivors was significantly lower that the initial level and the level of nonsurvivors *P<0.05 compared to the nonsurvivors, †P<0.05 compared to before treatment. FDP, fibrinogen degradation products TAT, thrombin-antithrombin complex (B) on day 7, serum KL-6 levels in survivor showed significant lower compared to that of nonsurvivors and serum KL-6 levels in nonsurvivors showed significant higher compared to before the administration of rhTM. *P<0.05 compared to the nonsurvivors, †P<0.05 compared to before treatment. IL-6, interleukin-6; HMG-1, high-mobility group-1 protein; KL-6, Krebs van den Lungen-6.5

Neutrophils and neutrophil elastase, which is released from activated neutrophils, play important roles in the endothelial injury and increased permeability associated with ARDS. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) involves pathological microthrombus formation that is followed by thrombolysis in the systemic circulation, which results in the consumption of coagulation factors and platelets. Microthrombus formation causes organ ischemia, which often leads to organ failure. The rate of complications of ARDS and DIC gradually increases in proportion to progression of the severity of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS).

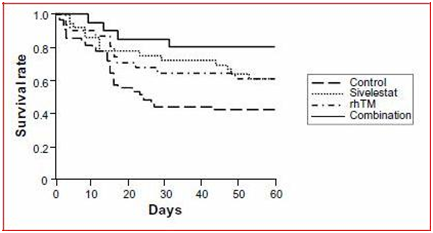

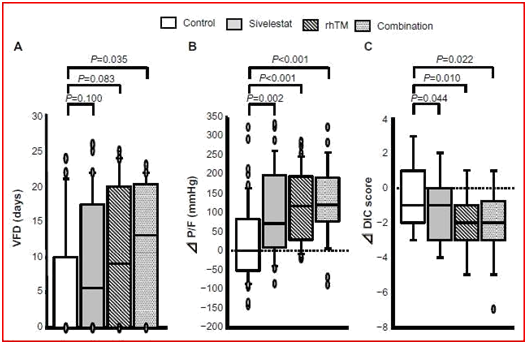

Kaplan–Meier survival curves are shown in (Figure 3). As compared with untreated controls, combination therapy significantly improved the 60-day survival rate of patients with ARDS and DIC. The survival rate with each single therapy alone tended to be higher than that of the non-ARDS patients, although these differences were not signifi-cant. The ventilator-free day results for the combination group of patients were significantly better than those for the non-ARDS patients (Figure 4A). P/F ratios and DIC scores at 7 days after a diagnosis of ARDS with DIC significantly improved with each single therapy and the combination therapy (Figure 4B & 4C).

Figure 3 Kaplan–Meier survival curves for acute respiratory distress syndrome patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation who did or did not receive sivelestat and/or rhTM. Statistical comparisons were made by log rank tests.3

Figure 4 Clinical efficacies of sivelestat, rhTM, and combination therapy. Efficacy assessments were made based on (A) VFD, (B) P/F, and (C) DIC score between before and at 7 days after a diagnosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome with DIC. Abbreviations: VFD, ventilator-free days; DIC, changes in disseminated intravascular coagulation; P/F, change in PaO2/FiO2 ratio.3

Anyhow, it was demonstrated that treatment with both sivelestat and rhTM could significantly prolong the survival of patients with ARDS and DIC and that a decision whether or not to administer both sivelestat and rhTM might be associated with the mortality of patients with ARDS and DIC. In addition, each single therapy regimen and the combination therapy resulted in improved respiratory and DIC status in ARDS and DIC patients. Thus, it was proposed that administering sivelestat and rhTM may be useful for patients with ARDS and DIC.3

None.

Author declare that there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2016 Zwer-Aliqa. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.