Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Review Article Volume 14 Issue 3

Assistant Professor, Anaesthesia, School of Excellence in Pulmonary Medicine, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Government Medical College, India

Correspondence: Dr. Rishi Kumar Gautam, MD, PDCC Fellowship- Interventional Pain Management, E-Pain, Assistant Professor, Anaesthesia, School of Excellence in Pulmonary Medicine, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Government Medical College, Jabalpur, India

Received: June 21, 2022 | Published: June 29, 2022

Citation: Gautam RK, Paswan AK. Revisiting the proposed hypotheses for trigeminal neuralgia with a note on its co-existence with Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. a review. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2022;14(3):99‒101. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2022.14.00517

Objective – to summarize the various hypotheses regarding the development of Trigeminal Neuralgia with a brief discussion about the causes for its co-existence with Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia, which has been seen infrequently.

Summary of background - Cranial nerve neuralgia is one of the most common pain syndromes attributed to the extreme (extremely) detrimental effects on middle age population who are more productive. The first documentation of Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) dates back second century AD by Aretaeus of Cappadocia, a contemporary of Galen.1 A study conducted from 1992 to 2002 in the UK reported an incidence of 26 per 100000 population per year.2 Its incidence is more prevalent amongst (the) female population with the ratio of 1.7:1, and increases with the age.

The purpose of my paper is to summarise all the possible mechanisms that lead to the development of Trigeminal neuralgia and to create an update regarding what we know about it now. My paper would also like to explore certain possibilities, which according to me, is (are) responsible for its infrequent occurrence with Glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Historical perspective

In (the) 1600s, the earliest documentation was made by 2 doctors known as Johannes Michael Fehr and Elias Schmidt of (the) Academy of Natural sciences. They famously describe it as severe, lancinating pain, with pain-free period still associated with intense anticipation of the next pain episode. In (the) near 1750s, Nicholas Andre said that it is due to the nerve disorder and hence is closely associated with the features of convulsion, he also coined the term tic douloureux. Fothergill’s disease was another term given by Dr. John Fothergill where he described the episode length as nearly half a minute.3 Though some literature still believes that Arataeus of Cappadocia gave some description of migraine headache in (the) second century though he did not delineate the presence of TN.4 Fothergill also said that this may not be associated with the convulsion but rather may due to presence of some kind of cancer, as he found 2 patients of Breast cancer among 14 TN patients he studied. However, in 1820, Charles Bell commented that tic douloureux is an entity completely limited to the trigeminal nerve after he separated this nerve from (the) Facial nerve.

Although we also should not forget John Hunter an anatomist and surgeon in (the) 1700s, (who) where (omit he) he said that any acute compression of (add a) nerve will result in painful sensation below the compression, which is what we observe in our daily practice as a pain physician.5

Epidemiology and demographics

A study in the US by Katusic et al. demonstrated the annual incidence of 4.8 per 100000 population.6 Incidence has also been found to be higher in Females with (a ratio) the ratio of 1.7:1 (F:M). Some studies have given (add a) preponderance of (the) right side more than the left which also is quite variable if you put forward your personal experience as a physician. Cases peaks after (the) age of 50 years and with (an) age of (a) group of less than 40are mostly (most) suggestive of a malignant etiology.7

The hypotheses: Though we think we know about the conditions that cause Trigeminal neuralgia, (omit but) but there are so many theories for it that, it is a tedious task to attribute and accept a single hypothesis. Hence, we can see that some or (of) the other new hypotheses keep on coming with the most recent being the Bio-resonance and Allergic hypothesis.

Fothergill’s disease: Chronologically speaking, as already put in the history, in the early 1700s, John Hunter postulated that some compression of the nerve may be the cause for the symptoms, then came Nicholas Andre in 1750s who said that the cause may be the something in close relation to what we see in convulsions, he kept the nerve lesion as the primary cause. Somewhere, near that time Fothergill said that some tumor may be leading to the production of this lancinating symptoms and named it Fothergill’s disease. In the early 20th century, Dandy, Gardner, and Miklos proposed the theory of vascular compression, but disappointingly there was very little acceptance for this theory.8 Janetta then further took this vascular compression theory and popularized it as the ‘Vascular compression’ theory.9 Janetta’s study mentions 4400 operative procedures where he mentions the Superior Cerebellar artery as the main culprit vessel compressing the Trigeminal nerve either at the brainstem or slightly distally.10

Kerr’s peripheral region hypothesis: In 1967, Kerr published an article mentioning the peripheral Trigeminal nucleus as the major cause leading to the production of symptoms. He argued that patients with pre-existing comorbidities like Atherosclerosis, Hypertension makes the nerve and the ganglion more vulnerable to superimposed pulsation by an aberrant vessel.11 In this same paper, he also proposed the convergence of impulses between the Spinal Trigeminal nucleus and the Gaessarian ganglion.

Central region hypothesis: King and Barnett injected alumina gel near the Spinal Trigeminal nucleus and demonstrated dysesthesia in the distribution of the Trigeminal nerve but instead of claiming that they have reproduced Trigeminal neuralgia, they gently proposed that the central mechanism cannot be ignored either.11

Both central and peripheral region: Calvin in his paper in 1976, stated that maybe both peripheral and central region plays a role in the establishment of the disease. They gave two assumptions that the symptom is due to the dorsal root reflex or is because of extra action potential generated at the altered sites of myelination in the nerve itself.12

Compression theory: Then came the compression theory by Dandy, Gardner, Jannetta, and Miklos, where they said that some form of external compression in the central myelin area at the Transitional zone and at (omit at) Root entry zone (REZ) may lead to demyelination and production of symptoms of TN (Figure 1).13

Ectopic electrogenesis and crossed after-discharge: Various studies and one by Rappaport did an electron microscopic study of the compressed portion and found areas of demyelination, dysmyelination, and a close approximation of the denuded axons leading to the production of symptoms. They also observed that these ultrastructural changes are more prominent when the compression by a pulsatile vessel. The close approximation of denuded axons eventually leads to ectopic electrogenesis and crossed after-discharge.14

Ignition theory:

From the above observation, an Ignition hypothesis was also proposed where after-discharge and ectopic electrogenesis from the damaged axons was proposed to be the pathology behind TN.15

Bio-resonance: A new theory in 2009 known as Bio-resonance theory was published by De-ze Jia, Gang Li, where they proposed that any structure in close vicinity of the nerve when is struck by its natural frequency leads to its resonance which also affects the nerve integrity leading to denudation and demyelination, finally resulting in facial pain. This turn (turns) outs to be a fascinating theory and the concepts of Natural frequency and resonance is (are) already well established.16

Allergies and atopy:

Allergies can also lead to nerve inflammation and neuritis leading to neuropathic pain. The basis is the activation of glial cells via endothelin -1 activation due to endothelin receptor.

type B activity (EDNRB). Glial cells when activated create a pro-inflammatory scenario causing inflammation of the affected nerves, in turn causing neuropathic syndromes like Trigeminal neuralgia. These findings were confirmed by using EDNRB antagonist BQ788 which halted the glial activation and ongoing neuritis.17

My proposal for the Co-existence of TN and GN with its response to treatment:

In my few years of clinical practice as a pain physician, I have come across a few cases of Trigeminal neuralgia who also had symptoms of Glossopharyngeal neuralgia, and all they responded to Radiofrequency ablation of the glossopharyngeal nerve. This was a fascinating finding which created a void to be filled by detailed thinking and some possibilities. So, I am proposing some possibilities which could be resulting in such findings.

Tonsillar branch of GNv and Palatine Branch of Trigeminal nerve (TNv):

The tonsillar branch Glossopharyngeal nerve (GNv) and the Palatine branch of TNv supply the tonsils. These branches are closely linked to each other. The overlapping pain symptoms between these two neuralgias could be due to the cross-talk and cross-fire attributed to ongoing proximal neuritis.

TNv nucleus and GNv nucleus:

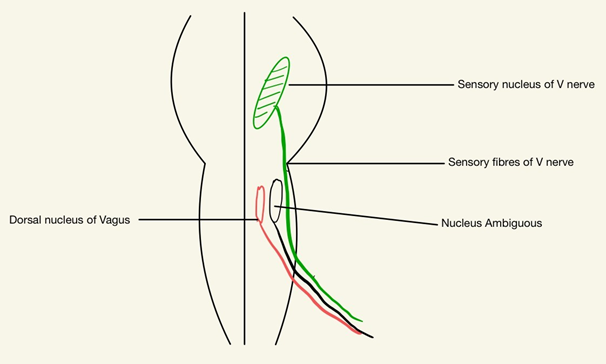

Sensory fibers arising from TNv nucleus in Pons which extend to Medulla and are very near to the origin of GNv nucleus and fibers in the medulla. This close proximity may be involved in the cross-firing and cross-talk where the pain from separate regions may converge and can give a picture of the co-existence of both entities (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Close Proximity of Glossopharyngeal nerve (GNv) and Trigeminal nerve (TNv) nucleus and exiting sensory fibres (fibers).

But few Glossopharyngeal neuralgia patients MRI Brain depicted a vascular loop either by the Superior cerebellar artery or Antero-inferior cerebellar artery, around the TNv’s origin, so here we may have to consider the common or adjacent nuclei of these nerves. The spinal nucleus of (the) Trigeminal nerve supplies the General Somatic Sensation to the Ear via GN and it also gives somatic sensation to the TNv distributed areas. The spinal nucleus of TNv thus incorporates sensation from the TNv, Facial nerve, GNv, and Vagus nerve. A vascular compression near this area or at the exit of these nerves can lead to neuritis in one or all these nerves and finally can produce overlapping symptoms.18

It is a fact that Chronic pain which originates Neuropathically has a major influence on psychological factors revolving around the patient. A) Catastrophising B) poor coping mechanisms C) Lack of Social support D) Pessimistic belief E) Poor job satisfaction and financial situations. These have also been linked with (a) greater occurrence of such complicated-coexisting neuralgias.19

Interventions like Peripheral nerve block or Radiofrequency ablation also has (have) the propensity to Centrally modulate the pain pathway activating the medial pain pathway leading to analgesia. So maybe the peripheral RFA of the Glossopharyngeal nerve (GNv) can lead to some form of central modulation in TNv as well thereby causing remission of mild-moderate Trigeminal neuralgia.20 (Figure 3)

Certainly, these are just hypotheses but yes, it has created a void for further studies and investigation. My intention here was to recapitulate and re-organize the proposed hypotheses for TN and I also wanted to put forward the unique scenario of (the) co-existence of TN with GN and the possible reasons for such co-existence, so that I can invite my peers to give an insight on such cases in their regular practice.

None.

None.

©2022 Gautam, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.